The relatively robust premaxilla is slightly

downcurved (see

Radinsky 1965) and has three incisors. These conditions are

shared with both Tapirus and Protapirus, although the premaxilla

of Tapirus is more robust than the others. The nasal process of the

premaxilla does not reach the nasal, extending posterodorsally to the level of

the posterior diastema, immediately anterior to the level of the first premolar.

At this point it lies just lateral to the margin of the narial opening, resting

on the dorsal edge of the facial maxilla. The CT data show the posterior margin

of the premaxilla extending as a wedge-shaped intrusion between the nasal and

facial surfaces of the maxilla. This relationship extends the entire sutural

length, from dorsal margin to the alveolar margin. Unlike Tapirus, the

third incisors are not caniniform. The interpremaxillary suture is open on the

AMNH skull, and the left and right sides are slightly displaced. Although

crushed, the flattened medial premaxillary margins of the nasoincisive incisure

suggest that the cartilaginous nasal septum was clasped by the premaxillae, or

possibly a maxilloturbinate that lined the narial face of the premaxillae

(Figure 6). Both elements embrace the nasal septum in Tapirus. This

contact with the cartilaginous nasal septum is situated immediately posterior to

the dorsal symphysis (see

Witmer et al. 1999). A single confluent palatine

fissure notches the palatal premaxilla.

The relatively robust premaxilla is slightly

downcurved (see

Radinsky 1965) and has three incisors. These conditions are

shared with both Tapirus and Protapirus, although the premaxilla

of Tapirus is more robust than the others. The nasal process of the

premaxilla does not reach the nasal, extending posterodorsally to the level of

the posterior diastema, immediately anterior to the level of the first premolar.

At this point it lies just lateral to the margin of the narial opening, resting

on the dorsal edge of the facial maxilla. The CT data show the posterior margin

of the premaxilla extending as a wedge-shaped intrusion between the nasal and

facial surfaces of the maxilla. This relationship extends the entire sutural

length, from dorsal margin to the alveolar margin. Unlike Tapirus, the

third incisors are not caniniform. The interpremaxillary suture is open on the

AMNH skull, and the left and right sides are slightly displaced. Although

crushed, the flattened medial premaxillary margins of the nasoincisive incisure

suggest that the cartilaginous nasal septum was clasped by the premaxillae, or

possibly a maxilloturbinate that lined the narial face of the premaxillae

(Figure 6). Both elements embrace the nasal septum in Tapirus. This

contact with the cartilaginous nasal septum is situated immediately posterior to

the dorsal symphysis (see

Witmer et al. 1999). A single confluent palatine

fissure notches the palatal premaxilla.

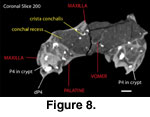

The maxilla lacks a canine, canine alveolus, and

the corresponding alveolar ridge on its facial surface. Otherwise, the maxilla

generally resembles that of Protapirus and Tapirus. Colodon

is similar to Tapirus in having a large conchal sinus recess and

apparently no maxillary sinus. The dorsal free edge of the facial maxilla is

thickened and bears a variably developed crista conchalis on its ventromedial

margin. Only fragments of the maxilloturbinate, which sutures to this crista,

remain. Viewed laterally, the profile of the narial margin is marked by two

broad scallops, which meet at the midpoint of the incisure margin as a low

peaked eminence (Figure 7). This arrangement is similar to Protapirus,

although the peak is more pronounced in Protapirus. Protapirus

also differs in having the peak associated with a shallow fossa on the facial

maxilla. The flattened and expanded medial surface of the peaked area of

Colodon and Protapirus is interpreted to be a sutural contact surface

for the septal portion of the maxilloturbinate. The septal maxilloturbinate of

Tapirus is a medially directed lamina that contacts the cartilaginous nasal

septum (see

Witmer et al. 1999). In coronal section the nasal face of the

maxilla is broadly concave below the crista conchalis (Figure 8), and compares

favorably with the conchal recess described for Tapirus by

Witmer et al.

(1999).

The maxilla lacks a canine, canine alveolus, and

the corresponding alveolar ridge on its facial surface. Otherwise, the maxilla

generally resembles that of Protapirus and Tapirus. Colodon

is similar to Tapirus in having a large conchal sinus recess and

apparently no maxillary sinus. The dorsal free edge of the facial maxilla is

thickened and bears a variably developed crista conchalis on its ventromedial

margin. Only fragments of the maxilloturbinate, which sutures to this crista,

remain. Viewed laterally, the profile of the narial margin is marked by two

broad scallops, which meet at the midpoint of the incisure margin as a low

peaked eminence (Figure 7). This arrangement is similar to Protapirus,

although the peak is more pronounced in Protapirus. Protapirus

also differs in having the peak associated with a shallow fossa on the facial

maxilla. The flattened and expanded medial surface of the peaked area of

Colodon and Protapirus is interpreted to be a sutural contact surface

for the septal portion of the maxilloturbinate. The septal maxilloturbinate of

Tapirus is a medially directed lamina that contacts the cartilaginous nasal

septum (see

Witmer et al. 1999). In coronal section the nasal face of the

maxilla is broadly concave below the crista conchalis (Figure 8), and compares

favorably with the conchal recess described for Tapirus by

Witmer et al.

(1999).

The ascending process of the maxilla extends

posterior to and lateral to the descending process of the nasals. At this area

the ascending maxilla is dorsally concave and contributes to the meatal

diverticulum trough. The lateral margin of the maxilla is raised and contacts

the frontal and lacrimals along the lacrimofrontal ridge. In Tapirus,

this ridge serves for attachment of the levator labii superioris muscles, a

prime mover of the proboscis (Witmer et al. 1999). The infraorbital foramen

opens at a level above P3/P4. CT data reveal an alveolar canal arising from the

infraorbital canal immediately posterior to the infraorbital foramen.

The ascending process of the maxilla extends

posterior to and lateral to the descending process of the nasals. At this area

the ascending maxilla is dorsally concave and contributes to the meatal

diverticulum trough. The lateral margin of the maxilla is raised and contacts

the frontal and lacrimals along the lacrimofrontal ridge. In Tapirus,

this ridge serves for attachment of the levator labii superioris muscles, a

prime mover of the proboscis (Witmer et al. 1999). The infraorbital foramen

opens at a level above P3/P4. CT data reveal an alveolar canal arising from the

infraorbital canal immediately posterior to the infraorbital foramen.

Posteroventrally, the maxillary tuber floors the orbit. The unerupted M3s of both specimens are deeply lodged within their crypts. The damaged palatal processes of the maxillae are notched anteriorly for a single palatine fissure. The perpendicular lamina of the palatines has an extended contact with the maxilla.

The horizontal laminae of the palatines are not

well preserved, but their choanal margin is near the level of M1/2. Note that

during the ontogeny of living tapirs the choanae migrate posteriorly with the

eruption of the molar series. Rostrally the horizontal laminae intrude between

the maxillae, to about P3 level. As in Tapirus, the posterior

perpendicular lamina of the palatine extends posterior to the anterior margin of

the choanae along the medial surface of the maxilla, extending to the posterior

face of the maxillary tuber, where there is a small posteriomedial suface for

the suture with the pterygoid. The pterygoid is not preserved. Although the

palatine foramina are damaged and difficult to see, the palatine canal is seen in

the CT data extending along the medial margins of the maxillary tuber (e.g.,

Figure 9), and opening into the orbit immediately posterior to the maxillae

tuber. This is similar to the palatine canal of Tapirus.

The horizontal laminae of the palatines are not

well preserved, but their choanal margin is near the level of M1/2. Note that

during the ontogeny of living tapirs the choanae migrate posteriorly with the

eruption of the molar series. Rostrally the horizontal laminae intrude between

the maxillae, to about P3 level. As in Tapirus, the posterior

perpendicular lamina of the palatine extends posterior to the anterior margin of

the choanae along the medial surface of the maxilla, extending to the posterior

face of the maxillary tuber, where there is a small posteriomedial suface for

the suture with the pterygoid. The pterygoid is not preserved. Although the

palatine foramina are damaged and difficult to see, the palatine canal is seen in

the CT data extending along the medial margins of the maxillary tuber (e.g.,

Figure 9), and opening into the orbit immediately posterior to the maxillae

tuber. This is similar to the palatine canal of Tapirus.

What is preserved of the nasals is similar to

those of Tapirus, having an anteriorly tapering rostral process; the

posteromedial margin of the rostral process with a small notch; and a short

descending process resting on the posterior ascending process of the maxillae.

Viewed dorsally, the rostral process is roughly triangular, widening posteriorly

to the posterior nasoincisive incisure. The anterior medial rostral process of

the nasals is broken. A median process of the frontals intrudes between the

nasals posteriorly (Figure 10). Lateral descending processes of the nasals

extend rostrally along the dorsal margins of the maxillae to the level of the

thickened dorsal stem of the maxilloturbinal.

What is preserved of the nasals is similar to

those of Tapirus, having an anteriorly tapering rostral process; the

posteromedial margin of the rostral process with a small notch; and a short

descending process resting on the posterior ascending process of the maxillae.

Viewed dorsally, the rostral process is roughly triangular, widening posteriorly

to the posterior nasoincisive incisure. The anterior medial rostral process of

the nasals is broken. A median process of the frontals intrudes between the

nasals posteriorly (Figure 10). Lateral descending processes of the nasals

extend rostrally along the dorsal margins of the maxillae to the level of the

thickened dorsal stem of the maxilloturbinal.

The maxilloturbinals are represented by fragments. As noted above, the thickened dorsal stem is only partially preserved (Figure 10). However, considering their fragmental nature, the arrangement of the crista conchalis and of the presumed sutural contact area for the septal maxilloturbinate (Figure 7) at the peaked narial border of the maxilla indicate that the maxilloturbinals were generally similar to those of Tapirus. The partially preserved vomer (Figure 8, Figure 9) has a deep septal sulcis, which lodged the cartilaginous nasal septum and the perpendicular plate of the ethmoid. Only fragments of the ethmoidal turbinals are preserved, although a delicate perpendicular plate can be seen in coronal and horizontal CT sections.

Two tubercles mark the facial face of the lacrimal, similar to the condition observed in Tapirus. The medial of these tubercles is continuous with the frontolacrimal ridge on the margin of the orbit. The lacrimal foramen, or foramina, and lacrimal canal are poorly preserved, but appear similarly positioned to those of Tapirus.

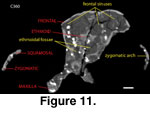

The frontals of Colodon resemble Tapirus,

being antero-posteriorly compressed, dorsally inflated, and having a median

process that intrudes between the nasals anteriorly. The CT data reveal

large frontal sinuses that invest almost the entire element (e.g.,

Figure 11).

This differs from the condition in Protapirus, which retains

elongated frontals having no sinus cavities that overlie the cranial cavity. The

meatal diverticulum fossa and trough are developed on the anterior frontals, and

on rostrolateral processes (Witmer et al. 1999). These rostrolateral processes

suture with the ascending maxillae, lacrimals, and posteriorly with the

posterior descending processes of the nasals. The supraorbital processes are

similar to those of Tapirus, extending posteriorly from the

frontolacrimal ridge.

The frontals of Colodon resemble Tapirus,

being antero-posteriorly compressed, dorsally inflated, and having a median

process that intrudes between the nasals anteriorly. The CT data reveal

large frontal sinuses that invest almost the entire element (e.g.,

Figure 11).

This differs from the condition in Protapirus, which retains

elongated frontals having no sinus cavities that overlie the cranial cavity. The

meatal diverticulum fossa and trough are developed on the anterior frontals, and

on rostrolateral processes (Witmer et al. 1999). These rostrolateral processes

suture with the ascending maxillae, lacrimals, and posteriorly with the

posterior descending processes of the nasals. The supraorbital processes are

similar to those of Tapirus, extending posteriorly from the

frontolacrimal ridge.