Megalodon (aka Otodus megalodon) has enjoyed a recent rise to fame. Even before its star turn, Megalodon was a standout. Almost all sharks are harmless – not Megalodon. With an estimated total length of 15-20 meters (already longer than a school bus) and vast jaws set with immense teeth, the prehistoric shark has the chops to take the lead in any creature feature. It first flirted with fame following the release of the notorious pseudo-documentary “Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives” in 2013. But Megalodon truly swam into the mainstream in 2018 when it starred in the eponymous blockbuster “The Meg” opposite Jason Statham.

Megalodon (aka Otodus megalodon) has enjoyed a recent rise to fame. Even before its star turn, Megalodon was a standout. Almost all sharks are harmless – not Megalodon. With an estimated total length of 15-20 meters (already longer than a school bus) and vast jaws set with immense teeth, the prehistoric shark has the chops to take the lead in any creature feature. It first flirted with fame following the release of the notorious pseudo-documentary “Megalodon: The Monster Shark Lives” in 2013. But Megalodon truly swam into the mainstream in 2018 when it starred in the eponymous blockbuster “The Meg” opposite Jason Statham.

No matter what these entertaining works of fiction say, no living Megalodon stalks modern seas – its fossils are between 15 and 3.6 million years old and its extinction is settled scientific fact. But scientific understanding is much less secure on other aspects of Megalodon biology. Body fossils of Megalodon are partial and rare. No complete Megalodon has ever been discovered. This means that important details in reconstructions of Megalodon – body shape, length, size, and weight – can only be estimated and are subject to change with new investigation.

An international team of shark researchers now proposes just such a change to Megalodon reconstructions in a new study in Palaeontologia Electronica. The team had its “eureka-moment” when it noticed one Megalodon specimen that contradicted previously published length estimates, said Kenshu Shimada, a DePaul University paleobiology professor and a co-leader of the new study. That specimen, an incomplete vertebral column, had a minimum possible length of 11.1 meters calculated simply by adding together the lengths of each individual vertebrae. However, when the dimensions of the vertebrae were used to estimate the length of the complete shark according to previously published calculations, the total length estimate was 9.2 meters. This result was a logical impossibility, since the total length of the shark, including its famous jaws, could not be less than the partial length of its spinal column.

The new study explores additional lines of evidence suggesting that the latest length reconstructions are inaccurate because they are based on the wrong assumption. Previous reconstructions gave Megalodon the same body shape as a great white shark. The new study argues that this intuitive comparison – between the largest living predatory shark and the largest shark of all time – is at odds with the available evidence. Instead, the new study reconstructs Megalodon as relatively longer and slenderer than the great white. “The new study strongly suggests that the body form of O. megalodon was not merely a larger version of the modern great white shark,” explained Philip Sternes, a University of California, Riverside, PhD candidate and the other co-leader of the study. He underscored that, “… previous total lengths of Megalodon are likely underestimated and will have to be re-evaluated once again.” However, this eye-catching result – the largest shark ever was even longer than we thought! – was not the focus of the study. Sternes elaborated that the effect of the revised body shape on the actual size (in terms of volume) or weight of Megalodon is unclear, saying, “In terms of the overall volume/weight of the animal, this once again will have to be re-evaluated in future studies. However, to give a definitive volume and weight to an extinct animal is rather difficult when there is a lack of preserved body form, especially for Megalodon.” A longer shark does not necessarily mean a bigger shark. DePaul University Master’s graduate Jake Wood emphasized the importance of new fossil discoveries in resolving this issue: “Moving forward, any meaningful discussion about the body form of O. megalodon would require the discovery of at least one complete, or nearly complete, skeleton of the species in the fossil record."

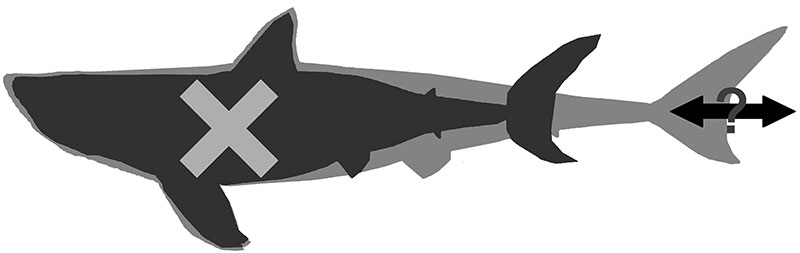

Comparison between previous (dark grey) and new (light grey) body reconstructions of Megalodon. Figure 4 from the paper.

Comparison between previous (dark grey) and new (light grey) body reconstructions of Megalodon. Figure 4 from the paper.

Instead, the study focused on how the new reconstruction would affect Megalodon as a living animal. This is an area where scientific understanding has changed recently, Sternes recounted: “Two previous studies have demonstrated Megalodon had a cruising speed slower compared to modern lamnids such as the white shark and mako shark. However, Megalodon was also empirically shown to be a regional endothermic shark [a shark which maintains some body parts at higher temperatures than the surrounding water].” The new study adds to this changing picture of Megalodon life with its implications for the digestive system, since a longer Megalodon implies a longer body cavity and digestive tract (or alimentary canal), Sternes explained. “Thus, when you take all things into consideration Megalodon most likely had an elongated alimentary canal that would provide more absorptive area and time,” he said.

Under this scenario, we get a new sense of the engine powering this massive shark. The long digestive tract would provide time and space for the shark to efficiently extract energy from the prey it consumed. The energy of the food would power the high metabolism also enabled by the shark’s regional endothermy. This metabolism would then enable the shark’s predatory lifestyle and allow it to catch enough prey to grow, reproduce, and keep the system fueled.

This is an exciting time for Megalodon research, as cutting-edge research, like this new study, changes the scientific reality behind this famous shark. Still, much remains unknown about Megalodon, pending future discoveries and analyses. Solutions to some problems await new fossil discoveries. But these gaps in our understanding are part of Megalodon’s appeal, according to Shimada. “The fact that we still don’t know exactly how O. megalodon looked keeps our imagination going,” he said, “The continued mystery like this makes paleontology, the study of prehistoric life, a fascinating and exciting scientific field.”

The new study is titled “White shark comparison reveals a slender body for the extinct megatooth shark, Otodus megalodon (Lamniformes: Otodontidae)”.

To discover more about this research, you can read the full publication (and the full list of authors) here.