SYSTEMATIC PALEONTOLOGY

(continued)

Superfamily Giraffoidea Gray 1821

Family

?Giraffidae Gray 1821

Genus

Progiraffa Pilgrim 1908

Diagnosis

Moderate-sized pecoran (m2-m3 length: ~ 5.3 cm).

Ossicones present. Brachyodont teeth with rugose enamel. Lower molars with

prominent metastylid well separated from the metaconid, lingual face of

metaconid and entoconid convex, m3 with robust entoconulid filling the lingual

wall. “Palaeomeryx‑fold” absent. Upper molars with subsidiary spurs

separate from labially directed postprotocrista and premetaconule crista.

Postmetaconule crista with bifurcation. Low lingual cingulum on posterior of

protocone.

Progiraffa exigua

Pilgrim 1908

Diagnosis

As for the genus.

New Material

Locality Z 117: 2376, medial phalanx.

Locality Z 120: Z 593, fragment of a right p2 or

p3; Z 2276, left astragalus; Z 2392, right lower molar fragment.

Locality Z 121: Z 2274, right distal metatarsal.

Locality Z 124: Z 162, posterior portion of skull.

Locality Z 126: Z 2391, distal left humerus.

Locality Z 137: Z 202, right cuboid-navicular; Z

210, proximal left femur.

Locality Z 203: DGK 15, left astragalus.

Locality Z 205: DGK 23, right astragalus; DGK 45,

left proximal femur; DGK 148, fragment of an ossicone; Y 41662, left mandible

with incomplete m1 and m2.

Locality Z 211: DGK 145, left unciform; DGK 204,

astragalus; DGK 215, right m1 or m2; DGK 291, right magnum-trapezoid.

Locality Z 212: DGK 188, right astragalus; DGK

200, right distal metacarpal.

Locality H 8115: H 208, left m3; H 664, right

M3(?).

Locality H 8125; H 312, right maxilla with

erupting P3 and DP4-M3.

Locality S 2: S 88, very worn left m1 or m2; S

412, left p3.

Locality S 4: S 48, incomplete left m3; S 495,

fragment of a right m1 or m2.

Locality S 6: S 154, right m1 or m2.

Locality S 15: S 305, right mandible fragment with

m1 or m2.

Locality Y 591: Y 24013, broken left cuneiform; Y

24020, distal metapodial; Y 24021, fragment of a left P4; Y 31676, left m1 or

m2.

Locality Y 592: Y 17554, incomplete left

astragalus; Y 31204, fragment of a left calcaneum; Y 31206, right P4; Y 47224,

medial phalanx; Y 47225, right fibula.

Locality Y 652: Y 23429, left cuneiform.

Locality Y 687: Y 47366, proximal phalanx.

Locality Y 721: Y 26598, incomplete right

astragalus; Y 26599, fragments of a right calcaneum.

Locality Y 738: Y 31148, fragment of a very worn

left upper molar.

Locality Y 744: Y 40808, incomplete right

astragalus.

Locality Y 747: Y 31733, left cuboid-navicular; Y

31735, left unciform; Y 31736, left cuneiform; Y 31739, left cuneiform; Y 31743,

incomplete right astragalus; Y 31745, fragment of a right astragalus; Y 31748,

left astragalus; Y 31760, medial phalanx; Y 31764, proximal portion of a

proximal phalanx; Y 31766, medial phalanx; Y 31768, distal metapodial; Y 31771,

distal portion of a medial phalanx; Y 31772, distal fragment of a proximal

phalanx Y 31773, medial phalanx; Y 31774, medial phalanx; Y 31775, distal

metapodial; Y 31776, distal metacarpal; Y 31784, right distal femur; Y 31787,

proximal left tibial epiphysis; Y 31789, fragment of a proximal right tibial

epiphysis; Y 31794, fragment of a left distal radius; Y 31797, lower left p3; Y

41455, distal metapodial; Y 46276, distal metapodial; Y 46277, left cuneiform; Y

46284, fragment of a left astragalus; Y 47475, proximal portion of a proximal

phalanx; Y 47476, proximal phalanx; Y 47477, fragment of left m1 or m2; Y 47478,

distal portion of a proximal phalanx; Y 47479, distal metapodial epiphysis.

Locality Y 780: Y 32920, small fragment of a right

astragalus.

Locality Y 802: Y 46236, right fibula; Y 46237,

left lunar.

Locality Y 843: Y 41451, distal portion of a

proximal phalanx.

The presence of three left cuneiforms at Locality

Y 747 indicates there are at least three individuals at that site.

Localities and Age

Pilgrim’s type specimen is from the equivalent of

the Chitarwata Formation at Dera Bugti, but its age is not known with any

certainty. The Zinda Pir sites are in the upper unit of the Chitarwata Formation

and the overlying Vihowa Formation, with an age range of approximately 20 to 17

Ma (Lindsay et al. this issue). The Manchar sites (GSP-H and GSP-S) are in the

lower part of the sequence (Raza et al. 1984; Hussain, personal commun., 1986)

and are of Lower and Middle Miocene age. The oldest Potwar sites (GSP-Y 747 and

Y 721) are at the base of the terrestrial sequence in the Salt Range and are

estimated to be about 18.3 Ma, while the youngest (GSP-Y 591 and Y 592) are

estimated to be about 16.0 Ma (Johnson et al. 1985).

Ginsburg et al. (2001) have

reported additional specimens from level 6 of

Welcome et al. (2001) in the Chitarwata Formation at Dera Bugti, to which the latter authors assign an Early

Miocene age.

Description

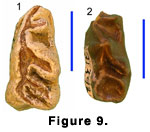

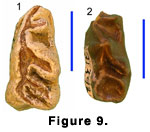

Lower Dentition. The available specimens

are all isolated premolars and molars, except for Y 41662, a mandible with

broken but otherwise well-preserved m1 and m2. The presumed p3’s (S 412 and

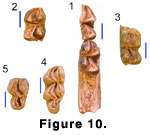

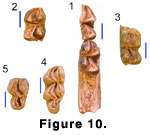

Y 31797) (Figure 9.1-9.2) are low and long, with faint labial incisions, a

large posterolingually directed metaconid that runs parallel to the equally

strong, oblique entoconid. The latter converges on a large, more transverse

entostylid to define a basin with a narrow lingual opening. The long anterior

crest is bifurcated, with a robust, lingually directed paraconid. In both

specimens there is a low cingulum just behind the base of the paraconid.

Lower Dentition. The available specimens

are all isolated premolars and molars, except for Y 41662, a mandible with

broken but otherwise well-preserved m1 and m2. The presumed p3’s (S 412 and

Y 31797) (Figure 9.1-9.2) are low and long, with faint labial incisions, a

large posterolingually directed metaconid that runs parallel to the equally

strong, oblique entoconid. The latter converges on a large, more transverse

entostylid to define a basin with a narrow lingual opening. The long anterior

crest is bifurcated, with a robust, lingually directed paraconid. In both

specimens there is a low cingulum just behind the base of the paraconid.

The lower molars (Figure 10.1-10.4) are brachyodont, with fine striations in the enamel. The obliquely situated

metaconid and entoconid have flattened labial faces but retain convex lingual

faces with weak development of lingual ribs in some cases. The premetacristid

contacts the anterolabial end of the preprotocristid, while the posthypocristid

reaches the labial side of the tooth, ending in a tubercle and nearly closing

off the posterolingual end of the median valley. In all specimens the

prehypocristid is separate from the preentocristid and trigonid cusps, even in

very advanced wear. None of the molars have even a vestige of a “Palaeomeryx‑fold,”

but all have large lingually displaced metastylids that are separated from the

metaconid by a strong vertical groove. The metastylid typically lies lingual to

the anterior end of the preentocristid. In two of the molars (S 305 and Y 31676)

(Figure 10.1-10.2) there is a small entostylid terminating the

postentocristid. This entostylid is distinct from the tubercle on the

posthypocristid. All the molars have low ectostylids and anterior and posterior

basal cingula.

The lower molars (Figure 10.1-10.4) are brachyodont, with fine striations in the enamel. The obliquely situated

metaconid and entoconid have flattened labial faces but retain convex lingual

faces with weak development of lingual ribs in some cases. The premetacristid

contacts the anterolabial end of the preprotocristid, while the posthypocristid

reaches the labial side of the tooth, ending in a tubercle and nearly closing

off the posterolingual end of the median valley. In all specimens the

prehypocristid is separate from the preentocristid and trigonid cusps, even in

very advanced wear. None of the molars have even a vestige of a “Palaeomeryx‑fold,”

but all have large lingually displaced metastylids that are separated from the

metaconid by a strong vertical groove. The metastylid typically lies lingual to

the anterior end of the preentocristid. In two of the molars (S 305 and Y 31676)

(Figure 10.1-10.2) there is a small entostylid terminating the

postentocristid. This entostylid is distinct from the tubercle on the

posthypocristid. All the molars have low ectostylids and anterior and posterior

basal cingula.

Both of the more complete m3’s (H 208 and S 48)

(Figure 10.3-10.4) have simple, crescent-shaped hypoconulids and a large

entoconulid that fills the space between the entoconid and hypoconulid, making

the lingual wall of the hypoconulid loop continuous. In S 48 the posthypocristid

contacts the entoconulid.

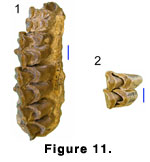

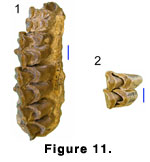

Upper Dentition. H 312 (Figure 11.1) is a

well-preserved maxilla with undamaged crowns of all the molars, a worn dP4, and

P3 exposed but still in its crypt. An unerupted P4 is also present, but only the

forming roots are visible and the crown is hidden within the maxilla. P3 has a

tall, anteriorly situated paracone with a strong labial rib and foreshortened

anterior crest. The posterior crest of the paracone is, in contrast, elongated

and blade-like. A large parastyle is separated from the paracone by a deep

vertical groove. The anteriorly situated protocone is connected to the parastyle

by a low crest forming a convex lingual wall. Within the posterior fossette of

the median valley there is a complicated, low spur of enamel connecting to the

inner wall of the postprotocrista and running anteriorly.

Upper Dentition. H 312 (Figure 11.1) is a

well-preserved maxilla with undamaged crowns of all the molars, a worn dP4, and

P3 exposed but still in its crypt. An unerupted P4 is also present, but only the

forming roots are visible and the crown is hidden within the maxilla. P3 has a

tall, anteriorly situated paracone with a strong labial rib and foreshortened

anterior crest. The posterior crest of the paracone is, in contrast, elongated

and blade-like. A large parastyle is separated from the paracone by a deep

vertical groove. The anteriorly situated protocone is connected to the parastyle

by a low crest forming a convex lingual wall. Within the posterior fossette of

the median valley there is a complicated, low spur of enamel connecting to the

inner wall of the postprotocrista and running anteriorly.

The upper molars are low crowned, with large

metaconules on M1 and M2. On M3 the metaconule is smaller than the protocone.

The parastyles and mesostyles are prominent on all the molars, the paracones

have very strong labial ribs and the metacones flat labial faces. On the M1 the

postmetaconule crista has a distinct bifurcation, and there are faint traces of

this condition on M2 and M3. The three molars of H 312 have a complex of low

enamel spurs near the junction of the postprotocrista and premetaconule crista.

On M2 and M3 these appear as a bifurcation of the worn premetaconule crista, but

on M1 it has a more complex shape. These spurs clearly have formed as structures

separate from the postprotocone and premetaconule crista, although with wear

they appear to merge with the centrally directed crista. Both M2 and M3 have a

low cingulum on the posterior face of the protocone. This cingulum originates

between the protocone and metaconule. At the base of the metaconule there is an

entostyle-like structure.

H 664 (Figure 11.2) is judged to be an M3 because,

although in advanced wear, it has no posterior interdental facet. In addition,

the metaconule is smaller than the protocone, as is typical of an M3. The molar

has a bifurcated postmetaconule crista, but it does not have the small spurs,

entostyle, nor protocone cingulum seen in the other specimens.

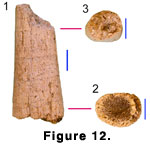

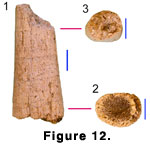

Cranial Remains. Ossicones: DGK 148 (Figure

12.1-12.3) is a small section of an ossicone (here used broadly to include the

branched structures of Climacoceras). The specimen is associated with a

mandible (Y 41662) and postcranials referred to Progiraffa exigua.

We assume, therefore, it also belongs to Progiraffa exigua. The ossicone

is possibly a midbeam segment, approximately 57.3 mm long. It is straight and

tapers toward the presumed distal end, with cross-section dimensions of 24.6 x

18.6 mm at the craniad end and 19.0 x 14.9 mm distally. In cross section it has

an oval shape, flattened on one side and with the greatest minor dimension

slightly off center. In cross section there is a gradual transition between a

very thin (3-6 mm at proximal end) outer zone of dense cortical bone and the

largely cancellenous interior. The surface has many fine grooves originating

from nutrient foramina at their proximal ends. These structures are scattered

uniformly about the surface and spiral counterclockwise about the long axis of

the bone when viewed from the distal end.

Cranial Remains. Ossicones: DGK 148 (Figure

12.1-12.3) is a small section of an ossicone (here used broadly to include the

branched structures of Climacoceras). The specimen is associated with a

mandible (Y 41662) and postcranials referred to Progiraffa exigua.

We assume, therefore, it also belongs to Progiraffa exigua. The ossicone

is possibly a midbeam segment, approximately 57.3 mm long. It is straight and

tapers toward the presumed distal end, with cross-section dimensions of 24.6 x

18.6 mm at the craniad end and 19.0 x 14.9 mm distally. In cross section it has

an oval shape, flattened on one side and with the greatest minor dimension

slightly off center. In cross section there is a gradual transition between a

very thin (3-6 mm at proximal end) outer zone of dense cortical bone and the

largely cancellenous interior. The surface has many fine grooves originating

from nutrient foramina at their proximal ends. These structures are scattered

uniformly about the surface and spiral counterclockwise about the long axis of

the bone when viewed from the distal end.

Skull: Z 162 (Figure 13.1-13.4) is the rear of a

broken skull. The specimen represents a medium-sized ruminant and, as

Progiraffa is the only known appropriate sized ruminant at this level, we

refer it to that species.

Skull: Z 162 (Figure 13.1-13.4) is the rear of a

broken skull. The specimen represents a medium-sized ruminant and, as

Progiraffa is the only known appropriate sized ruminant at this level, we

refer it to that species.

The specimen comprises the posterior of a damaged

cranium, lacking teeth and ossicones. Except for the nuchal crest and a small

remnant of the most dorsal part of the supraoccipital, the dorsal surface of the

cranium has been broken away, exposing a natural endocast of the brain. The

ventral surface has suffered only minor damage, while the supraoccipital region

is more or less intact. Although the frontals and skull roof have been

destroyed, the great thickness of the dorsal-lateral part of the lambdoidal

crest and orientation of the dorsal part of the supraoccipital suggest that the

skull roof was domed or that there may have been large posterior cranial

appendages. The supraoccipital is posteriorly projecting and laterally expanded

as it contacts the lambdoidal crest, with shallow pits for the semispinalis

capitis. Above the foramen magnum, the supraoccipital is slightly swollen, while

ventrally the paired occipital condyles are completely fused into a ring-like

structure, with the intercondyloid notch (incisura intercondyloidea of

Hamilton

[1973]) obliterated. The mastoid is narrowly exposed. On the ventral side of the

skull, the styloid process is posterolateral to and well separated from the

auditory bulla. The bulla is inflated and hollow, with an oval outline in

ventral view. It is well separated from the basioccipital and is not anteriorly

elongated. Consequently the middle lacerate foramen is left uncovered. The

basioccipital is posteriorly wide, narrowing anteriorly. It has well-developed,

laterally projecting condylar flexion stops (posterior tuberosities). A pair of

very subdued basilar tubercles is located posteriorly at about the level of the

posterior lacerate foramen, while anteriorly at the level of the foramen ovale

there is a second pair of very faint swellings. A median keel originates between

these latter swellings, running anteriorly onto the broken sphenoid. Anterior

and lateral to the posterior pair of basilar tubercles and just medial to the

auditory bulla there are paired irregular pits.

Postcranial Remains. Calcaneum: Y 31204 and

Y 26599 both preserve the fibular, cuboid, and much of the astragalar

articulations, and in the case of 26599 part of the calcaneal process. The

fibular articulation is typically pecoran, with a large convex posterior facet

and a smaller concave-convex anterior one. The bulbous posterior fibular

articulation has a medially projecting conical process with a distinct

posteromedial facet for the proximal lateral facet of the astragalus.

Fibula: Y 47225 is a distal fibula with a small

spine indicating it is a reduced remnant. Although damaged, the anterior tibial

facet is narrow and flat, and apparently did not curve medially.

Astragalus: The best preserved specimen is DGK

188, while all the others are broken or corroded by weathering. The

disto-lateral calcaneal facet is separated from the raised lateral edge of the

susentacular facet by a large sulcus, while the proximal lateral calcaneal facet

is confined to the edge of the susentacular facet and is separated from the

dorsal fibular facet. The cuboid condyle extends laterally, creating a distinct

notch on the lateral side of the astragalus, while the cuboid portion of the

condyle is cylindrical. The astragalus is narrow, with an approximate width to

length ratio of 1:1.7.

Cuboid-navicular: Z 202 is the more complete

specimen, but has been cracked and fractured, obscuring some of its features. Y

31723 is very well preserved, except for having lost the postero-ventral portion

of the astragalar articulation. In proximal view both are dorso-ventrally narrow

compared to the medial‑lateral diameter, with the cuboid‑astragalar facet being

slightly wider than the navicular‑astragalar one. The medial plantar process is

very prominent and the dorso‑medial angle of the navicular-astragalar

articulation is retracted. In distal view, the distal process does not extend to

the lateral margin of the anterior cuboid‑metatarsal facet and the relatively

broad posterior metatarsal articulation has a slightly inclined medial part

originating near the entocuneiform facet with a more horizontal lateral

extension. The facet for the 4th metatarsal lacks a posterior medial extension

bounding the groove for the tendon of the peroneus longus. Consequently the

peroneus groove is shallow and broad. The junction between the ectomesocuneiform

and endocuneiform articulations rises to form a low prominence, but both facets

are on the same level.

Lunar: The sole example (Y 46237) is too poorly

preserved to describe.

Cuneiform: With four well-preserved examples and a

fifth broken one, the cuneiform is the most common postcranial element. They

demonstrate slight morphological and size variation, but the stratigraphically

youngest (Y 23429) is typical in all respects. The unciform articulation is

relatively short and the disto-ventral process is directed ventrally rather than

being inflected distally. The pisiform articulation is narrow at its proximal

end, with its lateral margin being continuous rather than angled at the junction

with the ulnar articulation.

Magnum-trapezoid: The sole example (DGK 291) is

well preserved. Its dorsal ventral diameter is much larger than its

medio-lateral diameter, primarily because the lunar articulation is narrow and

not extended laterally. The junction between the lunar and scaphoid

articulations forms a high proximal keel. The inferior posterior unciform facet

is widely separated from the anterior one.

Unciform: The two referred specimens (DGK 145 and

Y 31735) differ somewhat in size and morphology, apparently reflecting

individual variation. DGK 145 is the smaller of the two. Its lunar articulation

has a flat, rectangular dorsal part that rises ventrally to form an almost

cylindrical condyle. The articulation for the cuneiform is relatively narrow,

without a marked lateral lip. The junction between the cuneiform and lunar

articulations is well differentiated, but low so that the two lie in nearly the

same horizontal plane. Y 31735 differs primarily in being about 10% larger and

in having a relatively wider posterior lunar articulation and a narrower one for

the cuneiform.

Metapodials: The fossils are all distal portions.

Three specimens (Z 2274, DGK 200, and Y 31776) preserve both the third and

fourth digits, while the remainder have only one side. Z 2274 is a metatarsal,

while DGK 200 and Y 31776 are metacarpals. The metatarsal gully appears to be

open in Z 2274, but the shaft is not preserved proximally enough to be certain.

In all specimens the keels of the distal articular surface extend dorsally but

do not project as far as they do ventrally. Consequently, in lateral view the

keels are strongly asymmetrical. The external condyle has a lipped rim which,

while stronger ventrally, also extends dorsally. The dorsal articular surface of

the external condyle is thus complete. Both the external and internal articular

surfaces terminate in a small pit on the dorsal side of the shaft.

Comparisons

The presence of ossicones leads us to tentatively

place Progiraffa in the Giraffidae.

Progiraffa exigua differs from middle

Miocene giraffids (sensu

Hamilton 1978) such as Giraffokeryx

punjabiensis Pilgrim 1911 and Injanatherium

Heintz, Brunet, and Sen

1981 in numerous ways (Colbert 1933;

Morales et al. 1987). These include the

presence in Progiraffa of a large, well-separated metastylid, a cingulum

on the protocone, and an enamel complex connecting the postprotocrista and

premetaconule crista. Progiraffa also seems to have a more sporadic

presence of a bifurcated metaconule and a more primitive basicranium with small

basilar tubercles and an oval auditory bulla that is well separated from the

basioccipital.

Progiraffa is similar to various primitive

giraffoids, such Propalaeoryx

Stromer 1926, Climacoceras

MacInnes

1936, Teruelia Moyą-Solą 1987, and Lorancameryx

Morales, Pickford,

and Soria 1993. The first of these, Propalaeoryx, is smaller and as far

as is known lacks cranial appendages. It also has a more anterior P3 protocone,

lacks entostyles on the molars, and the Namibian species P. austroafricanus

has a “Palaeomeryx‑fold” on the lower molars (Morales et al. 1999).

The ossicone described here for Progiraffa exigua could be a segment of

the branched, antler-like ossicone of Climacoceras, although it shows no

sign of secondary tines and its internal structure has a greater mass of

cancelleous bone and only a thin outer layer of dense cortical bone. The many

fine surface grooves and nutrient foramina on the Zinda Pir specimen are also

absent in Climacoceras africanus, although

Hamilton (1978) noted them in

C. gentryi. Dentally both species of Climacoceras differ from

Progiraffa. Their rather hypsodont lower molars have more compressed lingual

cusps with nearly parallel axes, metastylids that are not separated from the

metaconid, and m3 with the hypoconulid lingual wall incomplete. Climacoceras

also has a more anterior P3 protocone and narrower upper molars. Most of the

same dental characters differentiate Progiraffa from Lorancameryx

and Teruelia, the latter also lacking the bifurcated paraconid on p3.

The close similarity between Progiraffa and

Canthumeryx sirtensis

Hamilton 1973 (including Zarafa zelteni

Hamilton 1973) has been noted before (Moyą-Solą 1987,

Gentry 1994;

Ginsburg et

al. 2001). Canthumeryx is known principally from the dentition and

postcranials, to which a skull may be added if the synonymy of Zarafa is

accepted (Hamilton 1978, but see

Janis and Scott 1987). This taxon is near the

size of Progiraffa and nearly indistinguishable dentally. Possible points

of difference are a slightly stronger and more isolated metastylid in

Progiraffa and stronger bifurcation of the postmetacrista and greater

development of lingual basal structures in Canthumeryx (shown principally

in material originally attributed to Zarafa). The posterior and

basicrania of the skull of Progiraffa are also very similar to

Canthumeryx. Canthumeryx, however, has a flat skull roof, a large

swelling over the foramen magnum, an open intercondyloid notch, and it appears

to have a larger, more anterior pair of basilar tubercles. The slender ossicone

fragment (DGK 148) described here is also difficult to reconcile with the

massive bases seen in the referred skull of Canthumeryx, although

Churcher (1978; fig. 25.10) choose to reconstruct the specimen with slender,

spike-like ossicones.

Nyanzameryx pickfordi

Thomas 1984 and

Prolibytherium magnieri

Arambourg 1961 are two additional primitive giraffoids sharing some features of the skull and dentition with Progiraffa

(Geraads 1986). The isolated ossicone (DGK 148) is especially noteworthy, in

that it could be a segment of one of the slender ossicones of Nyanzameryx.

However, the nuchal area of the East African species is more gracile and less

projecting, while the basicrania has more anteriorly positioned basilar

tubercles. In addition, Nyanzameryx has lower molars with compressed

lingual cusps nearly parallel to the axis of the tooth, metastylids that are not

well separated from the metaconid, and m3 with the hypoconulid lingual wall

incomplete. It is also a much smaller taxon. Prolibytherium magnieri

shares one very distinctive feature with Progiraffa in that it has a

reduced intercondyloid notch, while the basilar tubercles are posteriorly

situated and very subdued. The great thickness of the skull roof of

Progiraffa suggests the presence of large and elaborate ossicones as in

Prolibytherium. The supraoccipital of Prolibytherium, however, does

not project so strongly posteriorly. There are also dental differences from

Progiraffa, principally in the possession of compressed lingual cusps that

are more parallel to the axis of the tooth, metastylids that are not well

separated from the metaconid, and an incomplete hypoconulid on m3.

Discussion

The initial description of Progiraffa was

very brief and included only one species (Pilgrim, 1908). In his subsequent,

more detailed account of Progiraffa

Pilgrim (1911) referred a second

species to the genus, one which

Lydekker (1883) had originally described as

Propaleomeryx sivalensis. Lydekker's single specimen is an isolated upper

molar, with few distinctive characters. It lacks the secondary complex of low

enamel spurs near the junction of the postprotocrista and premetaconule crista,

and is similar to the molar (H 664) from Sind. Except for its smaller size, the

latter specimen is virtually indistinguishable from Giraffokeryx punjabiensis.

The type specimen of Progiraffa exigua was until recently all that was

known of the taxon, but the new collections show the species is rather common.

The reference of both the ossicone (DGK 148) and

skull (Z 162) to one species is somewhat problematic. The construction of the

nuchal area of the skull (Z 162) suggests the cranial appendages were probably

robust and perhaps even similar to those of Prolibytherium. This

combination seems incompatible with the more spike-like ossicone DGK 148. The

skull fragment is about 19 Ma while the ossicone fragment is between 18 and 16

Ma (Lindsay et al. this issue). Both are from the Vihowa Formation.

The oldest specimen we attribute to Progiraffa

exigua is a poorly preserved distal humerus (Z 2391) from the upper unit

of the Chitarwata Formation, at a level we estimate to be 20 Ma. The specimen is

clearly a large pecoran, but might belong to the indeterminate large pecoran (Z

2031) from locality Z 127 rather than Progiraffa exigua. However,

it is appreciably larger than what we expect for a tooth the size of Z 2031 and

is an appropriate size for Progiraffa exigua.

On the Potwar Plateau Progiraffa exigua

persists up to at least 16 Ma. There are postcranial remains of a larger form

that is morphologically similar from sites between 16 and approximately 14 Ma.

While these might belong to another species of Progiraffa, we do not

describe nor discuss this larger form because it is only known from postcranial

elements. The cuneiform (Y 23429) from locality Y 652 is associated with a large

distal metapodial, which is likely to represent the larger pecoran, indicating

the two probably co-existed. After 14 Ma the still larger but morphologically

different remains of Giraffokeryx are found.

Lower Dentition. The available specimens

are all isolated premolars and molars, except for Y 41662, a mandible with

broken but otherwise well-preserved m1 and m2. The presumed p3’s (S 412 and

Y 31797) (Figure 9.1-9.2) are low and long, with faint labial incisions, a

large posterolingually directed metaconid that runs parallel to the equally

strong, oblique entoconid. The latter converges on a large, more transverse

entostylid to define a basin with a narrow lingual opening. The long anterior

crest is bifurcated, with a robust, lingually directed paraconid. In both

specimens there is a low cingulum just behind the base of the paraconid.

Lower Dentition. The available specimens

are all isolated premolars and molars, except for Y 41662, a mandible with

broken but otherwise well-preserved m1 and m2. The presumed p3’s (S 412 and

Y 31797) (Figure 9.1-9.2) are low and long, with faint labial incisions, a

large posterolingually directed metaconid that runs parallel to the equally

strong, oblique entoconid. The latter converges on a large, more transverse

entostylid to define a basin with a narrow lingual opening. The long anterior

crest is bifurcated, with a robust, lingually directed paraconid. In both

specimens there is a low cingulum just behind the base of the paraconid.