Discussion

AND CONCLUSIONS

Dentaries and teeth demonstrate the

presence of at least two sauropods in Malawi, Malawisaurus and

Karongasaurus. Based on differences in the morphology of the caudal

vertebrae that have been generally recognized as significant, titanosaurian

caudal vertebrae from Malawi also represent at least two taxa including

Malawisaurus and Titanosauridae indet. Malawisaurus has platycoelous

medial caudal vertebrae, whereas a procoelous middle or posterior caudal

vertebra is distinct from Malawisaurus and referred to Titanosauridae

indet. A third taxon may be represented by vertebra referred to Titanosauria

indet.

Phylogenetic analyses

that include Aeolosaurus, Alamosaurus, Andesaurus,

Antarctosaurus, Argentinosaurus, Epachthosaurus,

Malawisaurus, Nemegtosaurus, Neuquensaurus,

Opisthocoelicaudia, Quaesitosaurus, Rapetosaurus,

Saltasaurus, and Titanosaurus (Upchurch 1995,

1998,

1999;

Salgado et

al. 1997;

Curry Rogers and Forster 2001; see also

Wilson 2002) indicate that

Andesaurus and Malawisaurus are basal titanosaurians. In fact,

Malawisaurus is the most complete Early Cretaceous titanosaurian known. It

is represented by cranial elements, 18 cervical, 10 dorsal, six sacral, and 51

caudal vertebrae, 24 chevrons, pectoral elements, pelvic elements, and dermal

armor. Phylogenetic analyses also indicate that taxa with cylindrical teeth and

strongly procoelous posterior caudal vertebrae (or opisthocoelous in the case of

Opisthocoelicaudia) are more derived than those with broad teeth and

platycoelous middle and distal caudal vertebrae.

Skull Shape and

Morphological Diversity in Malawi Sauropods. Cranial material attributed to

titanosaurians includes one or two partial braincases of Titanosaurus

indicus from the Late Cretaceous of India (Berman and Jain 1982;

Chatterjee

and Rudra 1996), a maxilla from India (von Huene and Matley 1933), a partial

braincase and partial skull roof of Saltasaurus (PVL 4017-161) from the

Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Powell 1986,

2003), a premaxilla of Titanosauridae

indet. from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia (Scuitto and Martinez 1994), a premaxilla (PVL 3670-12) that

Powell (1979) identified as Laplatasaurus

but later referred to as Titanosauridae indet. (Powell 1986,

2003), a

fragmentary braincase from the Late Cretaceous of France (Le Loeuff et al.

1989), the braincase, quadrate, quadratojugal, squamosal, and the lower jaws of

Antarctosaurus wichmannianus (MACN 6904) from the Late Cretaceous

of Patagonia (von Huene 1929;

Powell 1986,

2003), two partial braincases of

Antarctosaurus septentrionalis from the Late Cretaceous of India (von Huene and Matley 1933;

Chatterjee

and Rudra 1996), a nearly complete

disarticulated cranium of Rapetosaurus from the Late Cretaceous of

Madagascar (Curry Rogers and Forster 2001,

2004), and the specimens of

Malawisaurus from the Early Cretaceous of Malawi.

There are two basic

morphs of sauropod skulls: one high and short, the other low and elongate

(Wilson 2002). The high, short morph is referred to as a macronarian skull,

whereas the low, elongate morph is generally referred to as a diplodocoid skull

(Coombs 1975;

McIntosh and Berman 1975;

Berman and McIntosh 1978;

Salgado and Calvo 1997;

Wilson 2002). The macronarian skull is present in Brachiosaurus,

Camarasaurus, Datousaurus, Euhelopus, Mamenchisaurus,

Omeisaurus, Shunosaurus, and most prosauropods, whereas the

diplodocoid skull is present in Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and

dicraeosaurids (Salgado and Calvo 1997; see also

Tidwell and Carpenter, 2003).

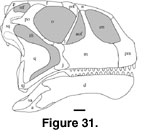

Comparison of cranial

features of Malawisaurus with macronarian and diplodocoid skulls

suggests that Malawisaurus had a high, short macronarian skull (Figure

31). The anterior section of the suture between premaxilla and maxilla appears

to have been nearly vertical as suggested by the highly angled articular surface

for the maxilla on the premaxilla. The high premaxilla also suggests that

Malawisaurus had a high, short, and blunt snout, and separate nares

positioned rostrally and facing laterally. The tooth row extends more than half

the length of the dentary. The mandibular symphysis is oblique to the long axis

of the mandible. The occipital condyle projected posteroventrally and the

basipterygoid processes projected ventrally. The quadrate axis was nearly

vertical, the pterygoid process of the quadrate was approximately perpendicular

to the long axis of the pterygoid, the pterygoid process was directed anteriorly

as in Brachiosaurus (Janensch 1935) and Camarasaurus (Osborn and Mook 1921), and the mandibular articulation was placed posteriorly beneath the

level of the occipital condyle. Thus, this study demonstrates that at least some

titanosaurians, including Malawisaurus, had high and short crania, as

compared to others such as Rapetosaurus, which had low and elongate

crania (Curry Rogers and Forster 2001,

2004).

Comparison of cranial

features of Malawisaurus with macronarian and diplodocoid skulls

suggests that Malawisaurus had a high, short macronarian skull (Figure

31). The anterior section of the suture between premaxilla and maxilla appears

to have been nearly vertical as suggested by the highly angled articular surface

for the maxilla on the premaxilla. The high premaxilla also suggests that

Malawisaurus had a high, short, and blunt snout, and separate nares

positioned rostrally and facing laterally. The tooth row extends more than half

the length of the dentary. The mandibular symphysis is oblique to the long axis

of the mandible. The occipital condyle projected posteroventrally and the

basipterygoid processes projected ventrally. The quadrate axis was nearly

vertical, the pterygoid process of the quadrate was approximately perpendicular

to the long axis of the pterygoid, the pterygoid process was directed anteriorly

as in Brachiosaurus (Janensch 1935) and Camarasaurus (Osborn and Mook 1921), and the mandibular articulation was placed posteriorly beneath the

level of the occipital condyle. Thus, this study demonstrates that at least some

titanosaurians, including Malawisaurus, had high and short crania, as

compared to others such as Rapetosaurus, which had low and elongate

crania (Curry Rogers and Forster 2001,

2004).

In addition, the titanosaurians

Nemegtosaurus (Nowinski 1971), and Quaesitosaurus (Kurzanov and

Bannikov 1983;

Curry Rogers and Forster 2001) had slender teeth restricted to

the anterior portion of the mandible, and also had low and elongate crania. If

that association of characters is general within titanosaurians, by implication

Karongasaurus would also have had a low and elongate cranium. Further,

phylogenetic analyses indicate that titanosaurians with slender teeth and which

have strongly procoelous middle and posterior caudal vertebrae are derived

relative to basal titanosaurians (Upchurch 1995;

Salgado et al. 1997;

Curry

Rogers and Forster 2001). Thus, both Karongasaurus and Titanosauridae

indet. from the Dinosaur Beds are derived relative to Malawisaurus. If

those characters are linked, the vertebra assigned to Titanosauridae indet. may

belong to Karongasaurus.

In any case, Malawisaurus and

Karongasaurus are two distinct titanosaurian taxa that coexisted in the

Early Cretaceous of Malawi and exhibited quite different morphological features,

certainly in their lower jaws and teeth, and probably also in their skull

shapes. Cylindrical teeth, an anteriorly restricted tooth row, and a long, low

skull shape evolved as a complex at least twice, once within diplodocoids and

once within titanosaurians. This character complex is functionally and

adaptively important for feeding. Its multiple origins, and its variance from

the macronarian skull pattern, implies that Malawisaurus and

Karongasaurus were ecologically distinct. If so, differences seen in the

lower jaw, teeth, and probably the skull of these herbivores were significant in

the ecological partitioning of their Early Cretaceous environment. Although the

macronarian and diplodocoid skull morphs are well known to occur together, for

example in the Jurassic of Africa, in the Early Cretaceous of Malawi

approximately equally divergent skull morphs are exhibited at a lower systematic

level among titanosaurians alone.

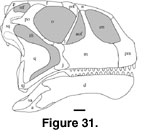

Comparison of cranial

features of Malawisaurus with macronarian and diplodocoid skulls

suggests that Malawisaurus had a high, short macronarian skull (Figure

31). The anterior section of the suture between premaxilla and maxilla appears

to have been nearly vertical as suggested by the highly angled articular surface

for the maxilla on the premaxilla. The high premaxilla also suggests that

Malawisaurus had a high, short, and blunt snout, and separate nares

positioned rostrally and facing laterally. The tooth row extends more than half

the length of the dentary. The mandibular symphysis is oblique to the long axis

of the mandible. The occipital condyle projected posteroventrally and the

basipterygoid processes projected ventrally. The quadrate axis was nearly

vertical, the pterygoid process of the quadrate was approximately perpendicular

to the long axis of the pterygoid, the pterygoid process was directed anteriorly

as in Brachiosaurus (Janensch 1935) and Camarasaurus (Osborn and Mook 1921), and the mandibular articulation was placed posteriorly beneath the

level of the occipital condyle. Thus, this study demonstrates that at least some

titanosaurians, including Malawisaurus, had high and short crania, as

compared to others such as Rapetosaurus, which had low and elongate

crania (Curry Rogers and Forster 2001,

2004).

Comparison of cranial

features of Malawisaurus with macronarian and diplodocoid skulls

suggests that Malawisaurus had a high, short macronarian skull (Figure

31). The anterior section of the suture between premaxilla and maxilla appears

to have been nearly vertical as suggested by the highly angled articular surface

for the maxilla on the premaxilla. The high premaxilla also suggests that

Malawisaurus had a high, short, and blunt snout, and separate nares

positioned rostrally and facing laterally. The tooth row extends more than half

the length of the dentary. The mandibular symphysis is oblique to the long axis

of the mandible. The occipital condyle projected posteroventrally and the

basipterygoid processes projected ventrally. The quadrate axis was nearly

vertical, the pterygoid process of the quadrate was approximately perpendicular

to the long axis of the pterygoid, the pterygoid process was directed anteriorly

as in Brachiosaurus (Janensch 1935) and Camarasaurus (Osborn and Mook 1921), and the mandibular articulation was placed posteriorly beneath the

level of the occipital condyle. Thus, this study demonstrates that at least some

titanosaurians, including Malawisaurus, had high and short crania, as

compared to others such as Rapetosaurus, which had low and elongate

crania (Curry Rogers and Forster 2001,

2004).