PALEONTOLOGY IN HONOR OF

WILLIAM R. DOWNS III (1950–2002)

Catherine Badgley, Lawrence J. Flynn, Louis L. Jacobs, and Louis H. Taylor

Catherine Badgley.

Museum of Paleontology, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109,

USA

Lawrence J. Flynn. Peabody

Museum, Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 USA

Louis L. Jacobs. Department of Geological Sciences, Southern Methodist

University, Dallas, Texas 75275 USA

Louis H. Taylor. Department of Earth Sciences, Denver Museum of Nature and

Science, Denver, Colorado 80205 USA

The

contributions in this issue of Palaeontologia Electronica honor the life

and work of William R. Downs III (1950-2002), known to most of his

acquaintances as Will, and to his Chinese colleagues as Dong Weilin. The

diversity of topics among these papers, their wide geographic range, and the

suite of seventy authors from a dozen different countries attest to his impact

on the field of vertebrate paleontology.

The

contributions in this issue of Palaeontologia Electronica honor the life

and work of William R. Downs III (1950-2002), known to most of his

acquaintances as Will, and to his Chinese colleagues as Dong Weilin. The

diversity of topics among these papers, their wide geographic range, and the

suite of seventy authors from a dozen different countries attest to his impact

on the field of vertebrate paleontology.

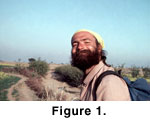

Will grew up in the Washington, D.C. area, but

from his college years onward, his home base was northern Arizona. He earned a

Humanities B.A. from Northern Arizona University and became fluent in Mandarin

Chinese through an immersion program in Hong Kong. He had no advanced degrees.

His vertebrate paleontology skills were self-taught. He learned from field

expeditions, from laboratory preparation, through listening and discussing at

scientific meetings, and through reading widely. He was a hard-working and

lively collaborator—in the field, in the lab, and as a co-author. He was

energetic, intense, stoic, and stubborn, and he had a gift for humor. People of

many cultures welcomed and appreciated him (Badgley

et al. 2004).

Gatesy et al. (this issue) said it well, “With little money and few

possessions, he carried with him an indefatigable spirit of curiosity and

seemingly endless energy.”

Will was an expert at collecting and preparing vertebrate fossils. In the field

he collected fossils ranging in size from shrews to dinosaurs. He had the

patience for painstaking excavation and the stamina for weeks of screen-washing.

In most of his field areas, he collected and processed many tons of

fossiliferous matrix to find the remains of microvertebrates within. In the

laboratory, he prepared specimens for research and exhibit. Fossils collected or

prepared by Will reside in the research museums and universities of three

continents.

Will

cut his teeth, geologically speaking, on the Mesozoic rocks of the Colorado

Plateau in the southwestern United States. His discovery of mammals in the Lower

Jurassic Kayenta Formation was a major event in North American vertebrate

paleontology. When Will showed George Gaylord Simpson (Simpson

1978; Laporte 2000)

the first tooth, Simpson turned slowly away from the microscope toward Will and

in his deliberate way said, “This is truly a great find.” If Simpson’s approval

had an effect on Will, no one could tell. He was already excited, and he would

stay that way. He never hid his enthusiasm. He was the same with everyone, lofty

or humble.

Will

cut his teeth, geologically speaking, on the Mesozoic rocks of the Colorado

Plateau in the southwestern United States. His discovery of mammals in the Lower

Jurassic Kayenta Formation was a major event in North American vertebrate

paleontology. When Will showed George Gaylord Simpson (Simpson

1978; Laporte 2000)

the first tooth, Simpson turned slowly away from the microscope toward Will and

in his deliberate way said, “This is truly a great find.” If Simpson’s approval

had an effect on Will, no one could tell. He was already excited, and he would

stay that way. He never hid his enthusiasm. He was the same with everyone, lofty

or humble.

Will was also an accomplished whitewater oarsman,

a skill he honed in numerous raft trips on the Colorado River through the Grand

Canyon and on other major rivers of the western United States. It was an outdoor

classroom for him. How could he not learn geology in such a setting? As a direct

result of the friendships built on southwestern rivers, he participated with a

team of structural geologists on a geological reconnaissance rafting trip on the

Yangbi River (a tributary of the Lancang Jiang, which becomes the Mekong River

in Laos) in western Yunnan, China (Molnar,

this issue; Winn and

Foster, this issue).

Will’s

later career focused primarily on three geographic areas – China, Pakistan, and

Africa – although the papers in this issue are adequate testimony that he would

go anywhere that opportunity, interest, and adventure coincided. Among his field

areas, China stands above the rest. The respect he had for China and the Chinese

people, and the respect they had for him, is expressed well in the dedication of

the paper by Wang et al. (this issue), “Will made a profound impact in Chinese

vertebrate paleontology at a time of maximum stress as the Chinese scientific

communities struggled to find their footing amid rapid changes of research

environment and science policy during the early days of economic reforms of the

country. Besides being one of the few western scientists who could read technical Chinese paleontological literature, Will inspired us with his single-minded dedication

to field paleontology, his love of adventure, his care for Chinese culture, and

his tireless promotion of Chinese vertebrate paleontology. “

Will’s

later career focused primarily on three geographic areas – China, Pakistan, and

Africa – although the papers in this issue are adequate testimony that he would

go anywhere that opportunity, interest, and adventure coincided. Among his field

areas, China stands above the rest. The respect he had for China and the Chinese

people, and the respect they had for him, is expressed well in the dedication of

the paper by Wang et al. (this issue), “Will made a profound impact in Chinese

vertebrate paleontology at a time of maximum stress as the Chinese scientific

communities struggled to find their footing amid rapid changes of research

environment and science policy during the early days of economic reforms of the

country. Besides being one of the few western scientists who could read technical Chinese paleontological literature, Will inspired us with his single-minded dedication

to field paleontology, his love of adventure, his care for Chinese culture, and

his tireless promotion of Chinese vertebrate paleontology. “

Two papers in this issue (Bever et al. and

Jokela

et al.) pay tribute to Will’s skill as a translator of Chinese scientific

literature and his generosity with the results. But every paper herein expresses

a tacit or explicit debt to Will Downs, some more directly than others. Several

papers are based on specimens – collected by Will – that contributed to the

authors obtaining their advanced degrees. All are based on friendship and the

influence that Will had. Matt Colbert, the grandson of the venerable Edwin

Harris Colbert (Colbert 1980;

1989) and the talented Margaret Matthew Colbert

(Colbert 1992;

Elliot 2000), who visited Flagstaff in the summers during the

1970s, wrote (Colbert, this issue), “My brother Denis and I would hang out there

pestering the scientists and staff. … The highlight of any research center visit

was the geology prep lab, where Will could be found sorting matrix or

air-scribing some fossil. He was extremely generous to us boys, always taking

time to share some off-color tale, to offer his seasoned opinion on the delicate

art of interacting with the ladies, or to help with one of our volunteer

projects …. Will was a major influence in my formative years….”

Thus,

the papers of this issue are, in addition to scientific contributions, vignettes

to a greater or lesser degree of the life and work of Will Downs, the things he

liked, the influence he had on his friends, or simply their consideration of

him. In addition, the publication of this tribute in Palaeontologia

Electronica has special appeal to us as editors for a number of reasons that

we think would have appealed to Will as well. There are no page limits.

Publication is efficient and fast and allows for creative illustration

techniques. It is cost effective. And it is available all over the world at no

direct cost to the user.

Thus,

the papers of this issue are, in addition to scientific contributions, vignettes

to a greater or lesser degree of the life and work of Will Downs, the things he

liked, the influence he had on his friends, or simply their consideration of

him. In addition, the publication of this tribute in Palaeontologia

Electronica has special appeal to us as editors for a number of reasons that

we think would have appealed to Will as well. There are no page limits.

Publication is efficient and fast and allows for creative illustration

techniques. It is cost effective. And it is available all over the world at no

direct cost to the user.

We would like to express our deep appreciation to

the editors of Palaeontologia Electronica, especially David Polly and

Whitey Hagadorn, for their help and assistance. We greatly appreciate working

with the congenial Jennifer Rumford. The editors and staff of Palaeontologia

Electronica work at the highest professional standards and their efforts are

changing the way publication in our science is done.

We also thank reviewers and others who have

contributed. We especially thank Diana Vineyard for her hard work in compiling

and keeping track of the vast numbers of loose ends, for converting files from

one format to another, and for being pleasant through it all. Dale Winkler, Kent

Newman, and Michael J. Polcyn helped us to solve various problems. With seventy

contributing authors, it is little surprise that we also utilized their

expertise in the review process. Additional reviewers include Pierre-Olivier

Antoine, Kenneth Angielzck, Jon Baskin, Robyn Burnham, Michael Caldwell, Pierre Mein,

Gregoire Metais, Donald Prothero, Jay Quade, Ray Rogers, Peter Rose, Bruce

Rubidge, William Sanders, Chris Sidor, Rob Van der Voo, and Jeff Wilson. We have

also been supported by The Saurus Institute and the Institute for the Study of

Earth and Man at Southern Methodist University.

Thanks to them all.

PE Editorial Number: 8.1.2E

Copyright: Coquina Press May 2005

The

contributions in this issue of Palaeontologia Electronica honor the life

and work of William R. Downs III (1950-2002), known to most of his

acquaintances as Will, and to his Chinese colleagues as Dong Weilin. The

diversity of topics among these papers, their wide geographic range, and the

suite of seventy authors from a dozen different countries attest to his impact

on the field of vertebrate paleontology.

The

contributions in this issue of Palaeontologia Electronica honor the life

and work of William R. Downs III (1950-2002), known to most of his

acquaintances as Will, and to his Chinese colleagues as Dong Weilin. The

diversity of topics among these papers, their wide geographic range, and the

suite of seventy authors from a dozen different countries attest to his impact

on the field of vertebrate paleontology.