TRANSLATION:

HIPPARION-FAUNA FOSSIL LOCALITIES IN PAO-TE-SHIEN, NW-SHANSI

(continued)

The excavation

of fossils for medical use constitutes a source of income for the people. It is

hard to tell how long it has been practiced; one estimate is 60-70 years.

However, when the large number of abandoned mines and the length of some still

in use are taken into account, an older age of the practice can be considered.

The quarrying commences in such a way that where conditions appear promising,

for example at a site where fossils occur on the surface, a horizontal tunnel

about 90 cm wide and high is excavated. Where a larger fossil concentration is

found, the tunnel can be enlarged into a chamber. If the nest, which at the

beginning of the activity was productive or in later phases of the activity was

recently being worked, is exhausted, excavation is continued arbitrarily in any

direction, in which activity only the common hardening of the clay in the

vicinity of the fossils can give an indication of the outcome of the chosen

direction. There are no deviations from the horizontal level, if small

exceptions are ignored.

The excavation

of fossils for medical use constitutes a source of income for the people. It is

hard to tell how long it has been practiced; one estimate is 60-70 years.

However, when the large number of abandoned mines and the length of some still

in use are taken into account, an older age of the practice can be considered.

The quarrying commences in such a way that where conditions appear promising,

for example at a site where fossils occur on the surface, a horizontal tunnel

about 90 cm wide and high is excavated. Where a larger fossil concentration is

found, the tunnel can be enlarged into a chamber. If the nest, which at the

beginning of the activity was productive or in later phases of the activity was

recently being worked, is exhausted, excavation is continued arbitrarily in any

direction, in which activity only the common hardening of the clay in the

vicinity of the fossils can give an indication of the outcome of the chosen

direction. There are no deviations from the horizontal level, if small

exceptions are ignored.

People often dig for four to five days or for one week

until another fossil nest is found. This working method explains the

irregularities and branching of the tunnels (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7). The tools used

are generally simple (see Figure 8). A relatively heavy pickaxe with a short

handle is the general tool used in the work. A small hatchet is used for

separating the fossils from the matrix and the teeth from the jaws. For

transportation of the material, a small wooden cart with four small wheels is

used. It is 1.3 m long, 60 cm wide, and 35 cm high. A flat basket on the cart

contains the excavated material. People especially trained for this task pull

the cart on all fours, using a harness that runs between the legs and over one

shoulder. Oil lamps typical for the region and placed in specially carved niches

or standing on suitable iron rods driven into the clay, are used for

illumination. In spring, the buyers for the Chinese drugstores come and buy the

available stock. One catty of bones is worth 6 cash [no units in original], and

1 catty of teeth is worth 6-8 copper cents.

People often dig for four to five days or for one week

until another fossil nest is found. This working method explains the

irregularities and branching of the tunnels (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7). The tools used

are generally simple (see Figure 8). A relatively heavy pickaxe with a short

handle is the general tool used in the work. A small hatchet is used for

separating the fossils from the matrix and the teeth from the jaws. For

transportation of the material, a small wooden cart with four small wheels is

used. It is 1.3 m long, 60 cm wide, and 35 cm high. A flat basket on the cart

contains the excavated material. People especially trained for this task pull

the cart on all fours, using a harness that runs between the legs and over one

shoulder. Oil lamps typical for the region and placed in specially carved niches

or standing on suitable iron rods driven into the clay, are used for

illumination. In spring, the buyers for the Chinese drugstores come and buy the

available stock. One catty of bones is worth 6 cash [no units in original], and

1 catty of teeth is worth 6-8 copper cents.

During the summer, mining activities

usually cease because of farming.

During the summer, mining activities

usually cease because of farming.

During his

travels, the author also visited Nan-Sha-Wa in the region of Ho-Ch’ü-Hsien [Hequ

County], 140 li [=70 km] north of Chi-Chia-Kou. There, also, the people excavate

the fossils of the Hipparion fauna. The fossil nests there seem to be larger,

but less filled with bones. However, the number of the mines is too small

(three, of which only two are being used) to allow any significant conclusions

to be made .

The matrix

there is sandier, and the immediate proximity of the bones is seldom infiltrated

by calcium carbonate. As in Chi-Chia-Kou, the tunnels are situated 25 m above

the Carboniferous layer and are covered by about 30 m of barren clay. See

illustration [Figure 5]. They are 1 m high and up to 3 m wide. The reason for

this is partly explained by the softer matrix and partly by the sparser

distribution of fossils. The pickaxe used is wedge-shaped, with a short,

straight edge. For transportation, a small wheelbarrow on a wooden wheel with a

basket tied to it is used.

A further

region that was visited during travel is Wu-Lan-Kou [Wulangou] in the region of

Fu-Ku-Hsien [Fugu County] in Shensi, 110 li [=55 km] west of Pao-Te-Hsien. A

host of tunnels is

situated

there, all in a very restricted space in a side ravine. The significance of the

fact that they all lie at the same height would not have been noted, had this

not also been noticed in Chi-Chia-Kou. Also there the material is sandy/clayey,

and the bones in contrast are more fragile than in Chi-Chia-Kou. Above the

fossil horizon, there is about 35 m of barren clay. The height above the

Carboniferous could not be established. Thus, it seems that the total thickness

of the Hipparion clay is the same in all three regions, and the position of the

fossil horizon is the same in each case. The working methods are the same as

those used in Chi-Chia-Kou.

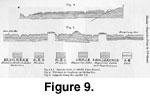

Now, a short

summary will be made. The extent of the Hipparion Clay in the east is up to the

Cambro-Ordovician limestone hills and in the west to the Yellow River towards

Shensi, as seen in the profile of Figure 9. To the north and south, the author

has not crossed the border of the Hipparion Clay, but observations and findings

support the reasoning that the fossil-bearing regions are former oases,

separated by areas devoid of fossils. By far the most important fossil-bearing

region is situated in Chi-Chia-Kou. Northwards from Chi-Chia-Kou, it is in Nan-Sha-Wa;

in the west, it is in Wu-Lan-Kou; and in the south, it is in the Kung-Lung-Yen [Kunlunyan]

(not visited), halfway between Pao-Te-Hsien and Lin-Chia-Yü [Linjiayu] (see

Figure 9). Taking into account the notable distances between the regions from

Chi-Chia-Kou—Nan-Sha-Wa being 145 li away, Wu-Lang-Kou 135 li, and Kung-Lung-Yen being 60 li

away—the vision of them as oases is not without foundation.

Now, a short

summary will be made. The extent of the Hipparion Clay in the east is up to the

Cambro-Ordovician limestone hills and in the west to the Yellow River towards

Shensi, as seen in the profile of Figure 9. To the north and south, the author

has not crossed the border of the Hipparion Clay, but observations and findings

support the reasoning that the fossil-bearing regions are former oases,

separated by areas devoid of fossils. By far the most important fossil-bearing

region is situated in Chi-Chia-Kou. Northwards from Chi-Chia-Kou, it is in Nan-Sha-Wa;

in the west, it is in Wu-Lan-Kou; and in the south, it is in the Kung-Lung-Yen [Kunlunyan]

(not visited), halfway between Pao-Te-Hsien and Lin-Chia-Yü [Linjiayu] (see

Figure 9). Taking into account the notable distances between the regions from

Chi-Chia-Kou—Nan-Sha-Wa being 145 li away, Wu-Lang-Kou 135 li, and Kung-Lung-Yen being 60 li

away—the vision of them as oases is not without foundation.

The excavation

of fossils for medical use constitutes a source of income for the people. It is

hard to tell how long it has been practiced; one estimate is 60-70 years.

However, when the large number of abandoned mines and the length of some still

in use are taken into account, an older age of the practice can be considered.

The quarrying commences in such a way that where conditions appear promising,

for example at a site where fossils occur on the surface, a horizontal tunnel

about 90 cm wide and high is excavated. Where a larger fossil concentration is

found, the tunnel can be enlarged into a chamber. If the nest, which at the

beginning of the activity was productive or in later phases of the activity was

recently being worked, is exhausted, excavation is continued arbitrarily in any

direction, in which activity only the common hardening of the clay in the

vicinity of the fossils can give an indication of the outcome of the chosen

direction. There are no deviations from the horizontal level, if small

exceptions are ignored.

The excavation

of fossils for medical use constitutes a source of income for the people. It is

hard to tell how long it has been practiced; one estimate is 60-70 years.

However, when the large number of abandoned mines and the length of some still

in use are taken into account, an older age of the practice can be considered.

The quarrying commences in such a way that where conditions appear promising,

for example at a site where fossils occur on the surface, a horizontal tunnel

about 90 cm wide and high is excavated. Where a larger fossil concentration is

found, the tunnel can be enlarged into a chamber. If the nest, which at the

beginning of the activity was productive or in later phases of the activity was

recently being worked, is exhausted, excavation is continued arbitrarily in any

direction, in which activity only the common hardening of the clay in the

vicinity of the fossils can give an indication of the outcome of the chosen

direction. There are no deviations from the horizontal level, if small

exceptions are ignored.

People often dig for four to five days or for one week

until another fossil nest is found. This working method explains the

irregularities and branching of the tunnels (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7). The tools used

are generally simple (see Figure 8). A relatively heavy pickaxe with a short

handle is the general tool used in the work. A small hatchet is used for

separating the fossils from the matrix and the teeth from the jaws. For

transportation of the material, a small wooden cart with four small wheels is

used. It is 1.3 m long, 60 cm wide, and 35 cm high. A flat basket on the cart

contains the excavated material. People especially trained for this task pull

the cart on all fours, using a harness that runs between the legs and over one

shoulder. Oil lamps typical for the region and placed in specially carved niches

or standing on suitable iron rods driven into the clay, are used for

illumination. In spring, the buyers for the Chinese drugstores come and buy the

available stock. One catty of bones is worth 6 cash [no units in original], and

1 catty of teeth is worth 6-8 copper cents.

People often dig for four to five days or for one week

until another fossil nest is found. This working method explains the

irregularities and branching of the tunnels (see

Figure 6,

Figure 7). The tools used

are generally simple (see Figure 8). A relatively heavy pickaxe with a short

handle is the general tool used in the work. A small hatchet is used for

separating the fossils from the matrix and the teeth from the jaws. For

transportation of the material, a small wooden cart with four small wheels is

used. It is 1.3 m long, 60 cm wide, and 35 cm high. A flat basket on the cart

contains the excavated material. People especially trained for this task pull

the cart on all fours, using a harness that runs between the legs and over one

shoulder. Oil lamps typical for the region and placed in specially carved niches

or standing on suitable iron rods driven into the clay, are used for

illumination. In spring, the buyers for the Chinese drugstores come and buy the

available stock. One catty of bones is worth 6 cash [no units in original], and

1 catty of teeth is worth 6-8 copper cents.

During the summer, mining activities

usually cease because of farming.

During the summer, mining activities

usually cease because of farming.