IVY

+ BEAN Break the fossil RECORD

IVY

+ BEAN Break the fossil RECORD

Annie Barrows (Author) and Sophie Blackall (Illustrator)

Chronicle Books, 2007

ISBN-13: 9780811862509

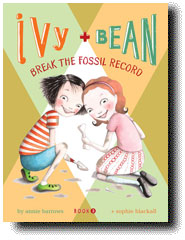

Rhiannon and I selected our first Ivy and Bean book, Ivy + Bean Break the Fossil Record for three reasons. First, the cover had two girls on it; second, the cover illustration was very funny, and third, the book promised to be about fossils and paleontology. Rhiannon at six years old (she will be seven by the time this review is published) already styles herself a “junior paleontologist,” and rightfully so I suppose. She identified her first fossils correctly, molluscs from the Pliocene Pinecrest Formation of Florida, when she was only three! And for the past two summers she has worked as a paid assistant in the paleontology lab at the California Academy of Sciences (earning money for rubber snakes and Barbie dolls). So, she was naturally intrigued by a book that claimed to tell the story of the world's youngest paleontologists, and also one that claimed to break the Fossil Record.

The book is the third in the Ivy and Bean series by Annie Barrows, and features second grade best friends Ivy and Bean. The pair are that often-used, but perhaps all too true odd couple. Ivy is studious, well-mannered and a little shy, while Bean is outspoken and a bit bored with her age. Any parent of a young girl reading this might recognize both characters immediately! This installment of the series opens with a classroom independent reading session, in which Bean is absolutely bored until the teacher gives her a special book, a book of world records. Meanwhile, Ivy is engrossed in a book about a character that should be familiar to all paleontologists, Mary Anning. Mary Anning was a young girl of the 19th century living in southern England. She is most famous for her discovery of the first complete ichthyosaur fossil at the age of 12, though she went on to have an illustrious career, also discovering the first species of plesiosaur. Bean entertains the class with hilarious stories of various record breakers (our favourite being the boy who stuck fifteen spoons to his face), but Ivy is entranced by Anning's story. Bean eventually decides to be a world record holder, and embarks on several unsuccessful but hugely entertaining attempts at various records, including Rhiannon's favourite, the stuffing of the most straws in one's mouth. (Thankfully, my co-author decided that this was not a good idea, though the straws had already been purchased). It is at this point that the story comes together: Ivy and Bean decide to break Mary Anning's record as the world's youngest paleontologist. What follows is a series of bone discoveries, childrens' misadventures, and the opening of a new museum. All in a single backyard!

This book could be dismissed as just another copy of a Cleary story, or as a silly pun on paleontological matters, but we think that it has more to offer. Ivy and Bean are both portrayed as believable characters, exhibiting all the charm of children at the brink of their ages of discovery. It is hardly ever obvious what the spark will be for any particular child. For Bean it was the discovery of world records, while for Ivy, it was that topic that many PE readers will identify with, paleontology. Barrows is clearly a keen observer of interactions among children, and that's what this book is all about. Never mind the scientific inaccuracies which crop up here and there; you'll also find those in every well respected popular news publication, and even, gasp, scientific journals. For Rhiannon, the summary of the book is simple: It features girls, the title is funny because “Record” means both world and fossil record, Ivy and Bean remind her of her own friends, and they built a museum with their own fossil discoveries. For me, the book was perfect bedtime reading with the little one, and was a funny and precious thing to share as a paleontological parent (I look forward to someday being a fossil parent). That's a lot of positive gain from a small and simple book.

Epilogue: Mary Anning's career as a paleontologist is noteworthy because of her discoveries, the contribution of those discoveries to our understanding of extinction, and her gender. She was able to support her family as necessary with fossil sales and patronage. She was eventually granted an annuity by the British Association for the Advancement of Science and was made an honorary member of the Geological Society of London. She never, however, held a paid position, nor was she elected to full membership in these associations, most likely because of her gender. She died of breast cancer at the young age of 47.