Bryozoans Described for the First Time from the Tamiami Formation (USA)

Bryozoans Described for the First Time from the Tamiami Formation (USA)

Jaleigh Pier

Bryozoans are tiny colonial animals that have a mineralized skeleton which typically encrusts onto hard surfaces in aquatic environments including rocks and shells. Dr. Emanuela Di Martino is a bryozoan specialist and describes them best:

“Bryozoans are small, aquatic, colony-forming invertebrate animals often mistaken for corals or seaweed. Each colony is comprised of genetically identical modular units called zooids. While zooids are microscopic, bryozoan colonies can range in size from a few millimetres to more than a metre wide.”

Like the cells of living sponges, bryozoan zooids have diverse forms and functions. There are specialized zooids for feeding, being either male or female for reproduction, and even those specific for defense called avicularia. Their physical appearance depends on their specific function within the colony. The great majority of bryozoans secrete calcareous skeletons, creating a lengthy fossil record dating back to the early Ordovician, about 475 million years ago.

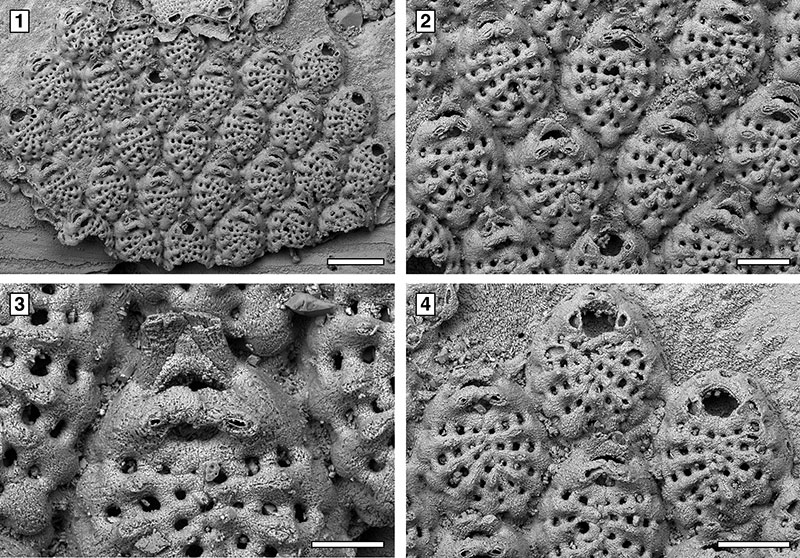

Spiniflabellum laurae, a fossil bryozoan species from the Tamiami Formation.

Spiniflabellum laurae, a fossil bryozoan species from the Tamiami Formation.

Dr. Di Martino is passionate about these little critters! After being first introduced to them through an undergraduate paleontology course, she hasn’t been able to learn enough about them. She also emphasizes their importance to the broader field of paleoecology:

“Their common and abundant presence in modern oceans as well as in the fossil record make them the ideal group to study the tempo and mode of biodiversity change through time, while their calcium carbonate skeletons make them ideal to study ocean acidification and potential vulnerability to climate change.”

Bryozoans can provide valuable insight for research revealing changes in biodiversity and climate acting as a link between modern and ancient oceans. Unfortunately, there are few bryozoan taxonomists, which are essentially experts in the classification and relationships of bryozoan species. For example, the Tamiami Formation of Florida (USA) bryozoan fauna have never been described. The only available information to date was an unpublished Master’s thesis of Echols in 1960. Dr. Di Martino and her fellow researchers set out to change that.

Since bryozoans commonly get ignored compared to other well-known invertebrates such as mollusks, arthropods, and corals there is a much greater chance of finding new species. Technological advances in microscopy, including a more widespread use of Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM) has also made the study of these tiny critters more accessible.

From this study twenty-nine bryozoan species were found, six of which were new species. In the world of bryozoans, twenty-nine is considered relatively “low” diversity. Dr. Di Martino explains “this is probably related to the fact that we focused on a single site and a particular type of substrate.” Although they solely looked at encrusters on the common jingle shell, bryozoans commonly cling to seagrass, algae, corals, rocks, and other shells. Most of the jingle shells were encrusted on both the inner and outer sides, indicating colonization likely happened after death.

Anomia simplex, also known as the jingle shell.

Anomia simplex, also known as the jingle shell.

An interesting aspect to bryozoan ecology, is that species often compete for space not only with each other, but with other encrusters such as barnacles, polychaetes (worms), and corals. Since their mineralized skeletons fossilize nicely, these interactions can be studied as battles preserved in time.

These ecological interactions observed in the Tamiami Formation are only discernable after determining a taxonomic baseline which was “necessary for further ecological analyses aiming to establish a ranking of species in a competitive hierarchy” says Di Martino.

You can read more about this study and see detailed pictures of described species here.