Specimen Z 271 (Figure 3.1-3.3) is a lightly worn

molar with the trigonid and anterior parts of the talonid cusps intact. Specimen

Z 2298 (Figure 3.4) is a very worn, but otherwise intact m3. The following

description is based on both teeth.

Specimen Z 271 (Figure 3.1-3.3) is a lightly worn

molar with the trigonid and anterior parts of the talonid cusps intact. Specimen

Z 2298 (Figure 3.4) is a very worn, but otherwise intact m3. The following

description is based on both teeth.

Infraorder Pecora

Superfamily Incertae sedis

Family

Gelocidae Schlosser 1886

Genus

Gelocus Aymard 1855

Fourth lower premolar slender, with small metaconid. Lower molars with cusps brachyodont; bunoselenodont protoconid and hypoconid; metaconid and entoconid conical and slightly compressed laterally; rudiment of paraconid present. Metaconid and entoconid crowded. Metastylid absent; trace of “Dorcatherium-fold” present. Prehypocristid joins posterior of protoconid, postmetacristid joins postprotocristid and preentocristid at center of tooth. (Modified from Viret 1961)

?Gelocus gajensis Pilgrim 1912

Small pecoran (m2-m3 length: ~ 3.4 cm). Enamel rugose. Without remnant of paraconid, but with pre- and postcristids of metaconid and entoconid very strongly differentiated. Faint fissure on metaconid with a raised lingual edge (cf. “Dorcatherium-fold”) and an antero-lingual groove on the entoconid.

Locality Z 108: Z 271, anterior half of a barely worn m3; Z 2298 very worn right m3.

Known from only Locality Z 108 in the lower part of the Chitarwata Formation. Late Oligocene and approximately 25 Ma (Lindsay et al. this issue).

Specimen Z 271 (Figure 3.1-3.3) is a lightly worn

molar with the trigonid and anterior parts of the talonid cusps intact. Specimen

Z 2298 (Figure 3.4) is a very worn, but otherwise intact m3. The following

description is based on both teeth.

Specimen Z 271 (Figure 3.1-3.3) is a lightly worn

molar with the trigonid and anterior parts of the talonid cusps intact. Specimen

Z 2298 (Figure 3.4) is a very worn, but otherwise intact m3. The following

description is based on both teeth.

The molars are brachyodont, with rugose enamel, bunoselenodont protoconid and hypoconid, and cuspidate metaconid and entoconid. In an unworn condition the metaconid was probably slightly taller than the protoconid. On the very worn specimen Z 2298 the trigonid is slightly narrower than the talonid. The metaconid and entoconid are both transversely narrow, with convex labial and lingual faces and long axes parallel to the long axis of the tooth. The anterolingual face of the protoconid is convex as in tragulids, not concave as in pecorans. There is no trace of a metastylid.

A short, distinct premetacristid contacts the short preprotocristid just above the low anterior cingulum, leaving a forward-facing anterior fossette that was probably open until an advanced wear stage. The postmetacristid is a swollen crest, bounded on the lingual side by a fine and indistinct crease. Towards the apex of the metaconid the crease becomes a faint fissure with its lingual edge raised as a barely differentiated crest. This is presumably the vestige of a “Dorcatherium-fold.” Similarly, on the posterior of the protoconid, there is a scarcely discernable raised area that could be a vestige of a “Tragulus-fold.” The postmetacristid is nearly vertical and the same length as the steeply descending postprotocristid. The two crests join to form a deep “V” that contacts the preentocristid without forming a common stem as in lophiomerycids.

The entoconid is anterior to the hypoconid and crowded against the rear of the metaconid. A very prominent preentocristid passes down its front, slightly labial to the midline of the cusp. This preentocristid is very sharply set off from the antero-lingual surface of the entoconid, producing a suggestion of an entoconid groove. A parallel lingual fold (“Zhailimeryx-fold”), however, is not preserved and, if it ever existed, it could not have extended to the base of the entoconid. The prehypocristid is directed anteriorly towards the posterior of the trigonid and does not contact the postmetacristid-preentocristid complex. The posthypocristid extends to the lingual margin of the tooth and the postentocristid is absent, leaving the posterior fossette narrowly open. Only Z 2298 preserves the posterior part of m3. It comprises a very large crescent-shaped hypoconulid, the antero-labial end of which contacts the posthypocristid at the midline of the tooth. There is a short, low crest that extends anteriorly from the hypoconulid along the lingual edge of the tooth, but fails to reach the posterior of the entoconid, leaving the lingual wall incomplete. A modest anterior basal cingulum arises at the base of the preprotocristid and passes around the front of the tooth to the lingual side. Finally, there is a low ectostylid that is possibly formed from a labial cingulum and a weak antero-labial cingulum on the hypoconulid.

The size and general morphology of the two Zinda Pir molars suggest reference to Pilgrim’s ?Gelocus gajensis, while its larger size precludes reference to“Gelocus” indicus Forster-Cooper 1915. Absence of a metastylid precludes reference to a number of small Oligocene pecorans, including Prodremotherium Filho, 1877, Notomeryx Qiu 1978, and Gobiomeryx Trofimov 1957. The absence of a well-formed “Dorcatherium-fold” precludes not only tragulids, but also Bachitherium Filhol 1882. Absence of a well-defined and deep “Zhailimeryx-fold” and a strong paracristid, together with more conical lingual cusps preclude reference to Indomeryx Pilgrim 1928 (Métais et al. 2000; Tsubamoto et al. 2003).

Pilgrim (1912) based his species on a single specimen, which he very briefly described and questionably referred to Gelocus. The type specimen came from deposits near Dera Bugti, at the “base of the Gaj” (Pilgrim 1912, caption to plate XXV). In his use of the “Gaj Formation,” Pilgrim was referring to what is now called the Chitarwata Formation (Downing et al. 1993). It seems likely that Pilgrim’s specimen came from the lowest fossiliferous levels at Dera Bugti and is approximately contemporaneous with the material from Locality Z 108. If so, this material could be as old as Early Oligocene (Welcomme et al. 2001), although we prefer a Late Oligocene age for the site.

The presence of a strong premetacristid on the ?Gelocus gajensis type and the Zinda Pir fossils would seem to preclude reference to Gelocus (Janis 1987). However, we follow Pilgrim in tentatively making that reference because of the absence of a metastylid combined with relatively conical lingual cusps and faint trace of a “Dorcatherium-fold.” It seems likely to us that the Bugti and Zinda Pir species represents an undescribed genus, but because of the fragmentary state of our material we do not think it is advisable to base a new taxon on it.

Superfamily ?Cervoidea Goldfuss 1820

Family

Incertae sedis

Genus Walangania Whitworth 1958

Small pecoran (m2-m3 length: ~ 2.8 cm). Frontal appendages unknown, likely absent. Enamel of cheek teeth finely rugose. The p1 possibly present, p3 and p4 with strong labial incision, oblique entoconid, and transverse entostylid on p4. Metaconid of p4 variable, with slight development of posterior flange; anterior crest weakly or not bifurcated. Lower molars brachyodont and selenodont. Metaconid and entoconid slightly oblique, compressed, with small metastylid situated lingual to the posterior end of postmetacristid. “Palaeomeryx ‑fold” variably present. P3 with weakly concave lingual wall anterior to the protocone. Upper molars brachyodont, large metaconules on M1 and M2. Paracone with strong labial rib, metacone rib feeble or absent. Strong parastyle, metastyle not distinct. Subsidiary crests present in the anterior fossette and separate from posteriorly directed postprotocrista. Limbs of advanced pecoran type. (Modified from Whitworth 1958).

Walangania africanus (Whitworth 1958)

As for the genus.

Napak I: BUMP 390, heavily worn right upper M1 or M2; BUMP 391, left DP3; BUMP 396, astragalus; BUMP 584, left mandible fragment with m2.

Napak IV: BUMP 23, worn left M3(?).

Napak IX: BUMP 721, right mandible fragment with p4-m2; BUMP 722, right mandible fragment with p3-m1.

Napak CC: BUMP 103, left proximal radius and distal humerus; BUMP 105, right proximal radius; BUMP 274, right maxilla with erupting P3, P4 in crypt, and DP4-M3; BUMP 450, left mandible fragment with alveoli for p1 and p2, and crown of p3; BUMP 800, incomplete m1 or m2.

Moroto II: BUMP 178, left proximal metatarsal; BUMP 552, incomplete left m3.

The type of Walangania africanus is from Songhor in western Kenya, and the species is widely distributed throughout the Early Miocene sites of East Africa, with an age range of approximately 17.8 Ma to 21 Ma. Radiometric dating has shown that the Moroto fossil localities are older than 20.6 Ma (Gebo et al. 1997), while the Napak localities are thought to be approximately 19 Ma using radiometric dating and faunal correlations with other sites in East Africa (Bishop et al. 1969; Drake et al. 1988; Pickford 1981).

Whitworth’s (1958) initial description and subsequent discussions (Janis and Scott 1987; Pickford 2002) provide a useful account of the morphology of this taxon and the range of variation encompassed within it. Here we describe additional dental material that clarifies some points.

Lower Dentition.

Whitworth (1958, p. 20)

noted variation in the premolars, which is also seen in the material discussed

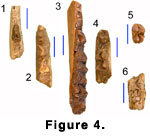

here. BUMP 450 (Figure 4.1) preserves the alveolus of the posterior root of a

more anterior tooth, which in this specimen is not separated by a diastema from

the anterior root of p2. The crown of p3 of BUMP 450 has a weak labial incision

and a minute cusplet on a posterolingually directed crest that is suggestive of

a metaconid. The equivalent crest on the p3 of BUMP 722 (Figure 4.2) is barely

discernable, with no hint of the cusplet. The p4 of this latter specimen has a

strong labial incision, compressed heel, and an oblique entoconid and large

transverse entostylid that together form a basin with a narrow lingual opening.

The metaconid is indistinct and the anterior crest (or parastylid) is relatively

long and simple, with no development of a paraconid. The p4 of BUMP 721 (Figure

4.3) conforms closely to that of Whitworth’s type from Songhor. It has a marked

labial incision and a distinct metaconid that is much lower than the protoconid.

There is a low lingual extension of the metaconid that runs forward to connect

with the anterior portion of the anterior crest. However, the anterior crest is

simple with no suggestion of the bifurcation into a paraconid and parastylid

seen in the type. Both BUMP 722 and 721 have a very slight posterior flange on

the p4 metaconid.

Lower Dentition.

Whitworth (1958, p. 20)

noted variation in the premolars, which is also seen in the material discussed

here. BUMP 450 (Figure 4.1) preserves the alveolus of the posterior root of a

more anterior tooth, which in this specimen is not separated by a diastema from

the anterior root of p2. The crown of p3 of BUMP 450 has a weak labial incision

and a minute cusplet on a posterolingually directed crest that is suggestive of

a metaconid. The equivalent crest on the p3 of BUMP 722 (Figure 4.2) is barely

discernable, with no hint of the cusplet. The p4 of this latter specimen has a

strong labial incision, compressed heel, and an oblique entoconid and large

transverse entostylid that together form a basin with a narrow lingual opening.

The metaconid is indistinct and the anterior crest (or parastylid) is relatively

long and simple, with no development of a paraconid. The p4 of BUMP 721 (Figure

4.3) conforms closely to that of Whitworth’s type from Songhor. It has a marked

labial incision and a distinct metaconid that is much lower than the protoconid.

There is a low lingual extension of the metaconid that runs forward to connect

with the anterior portion of the anterior crest. However, the anterior crest is

simple with no suggestion of the bifurcation into a paraconid and parastylid

seen in the type. Both BUMP 722 and 721 have a very slight posterior flange on

the p4 metaconid.

The lower molars (Figure 4.4 -4.6) are brachyodont, with a faint “Palaeomeryx‑fold” on the unworn or lightly worn teeth (Figure 4.5). On the anterior molars the metasylid is well separated from the metaconid and situated lingual to the posterior end of the postmetacristid. The unworn, but damaged m3 from Moroto II (BUMP 552) (Figure 4.6) appears to have had only a minute metastylid and a large entoconulid.

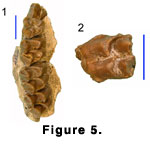

Upper Dentition. The most significant new

specimen is BUMP 274 (Figure 5.1), a well-preserved maxilla with undamaged

crowns of P3, DP4, and all the molars. An uerupted P4 is also present, but only

the labial face of the tooth is exposed. P3 has a tall, anteriorly situated

paracone with a strong labial rib. The posterior crest of the paracone is an

elongate blade and a large parastyle is separated from the paracone by a deep

vertical groove. The protocone is situated slightly anterior to the center of

the tooth and connected to the parastyle and metastyle by low crests. The

lingual crest is weakly concave in front of the protocone. Posterior to the

protocone and within the median valley a very low longitudinal spur of enamel is

attached to the inner face of the postprotocrista. This is presumably serially

homologous to the P4 structure referred to variously as an “accessory crest”

(Hamilton 1973, p. 77) or a “transverse crest” (Gentry 1994, p. 138) and to what

Whitworth (1958, p. 22) referred to as “subsidiary crests” on the molars.

Upper Dentition. The most significant new

specimen is BUMP 274 (Figure 5.1), a well-preserved maxilla with undamaged

crowns of P3, DP4, and all the molars. An uerupted P4 is also present, but only

the labial face of the tooth is exposed. P3 has a tall, anteriorly situated

paracone with a strong labial rib. The posterior crest of the paracone is an

elongate blade and a large parastyle is separated from the paracone by a deep

vertical groove. The protocone is situated slightly anterior to the center of

the tooth and connected to the parastyle and metastyle by low crests. The

lingual crest is weakly concave in front of the protocone. Posterior to the

protocone and within the median valley a very low longitudinal spur of enamel is

attached to the inner face of the postprotocrista. This is presumably serially

homologous to the P4 structure referred to variously as an “accessory crest”

(Hamilton 1973, p. 77) or a “transverse crest” (Gentry 1994, p. 138) and to what

Whitworth (1958, p. 22) referred to as “subsidiary crests” on the molars.

The upper molars are low crowned, with large metaconules on M1 and M2 and a reduced metaconule on M3. The parastyles and mesostyles are strong on all the molars. The paracones have very strong labial ribs with deep grooves before them, and the metacones have only faint ribs. On the M1 the postmetconule crista has a distinct bifurcation. There is a suggestion of this structure in a faint swelling of the enamel of M2, but it is lacking on M3. All the molars of BUMP 274 and BUMP 23 (Figure 5.2) have a small and low set of enamel spurs near the junction of the postprotocrista and premetaconule crista. The form varies among the teeth, but in general the spurs have a “Y” shape and presumably correspond to the subsidiary crests noted by Whitworth (1958, p. 22). The spurs wear to form a small enamel island. All three molars of BUMP 274 have minute entostyles but not the protocone cingulum described below for Bugtimeryx pilgrimi. In BUMP 23 the entostyle is larger and more pillar-like. In all specimens the entostyle is attached to the anterior base of the metaconule and is possibly a remnant of a lingual cingulum.

Walangania has been shown to differ from the contemporary African Propalaeoryx Stromer 1926 and “Gelocu” whitworthi Hamilton 1973. However, it has not been discussed in the context of Late Oligocene/Early Miocene pecoran ruminants, other than for general reviews such as Janis and Scott (1987) and Gentry (1994). Both noted its close similarity to primitive Early Miocene cervoids from Europe and have suggested its affinities lie with Miocene cervoids. We do not attempt a more detailed comparison to European forms here because we have not reviewed the very extensive East African collections. Comparison to Bugtimeryx, based primarily on the new Napak and Moroto specimens as well as published material, follows description of additional material of Bugtimeryx in the next section.

Whitworth (1958) published descriptions of Early Miocene ruminants from East Africa, naming the species Walangania gracilis and Palaeomeryx africanus. Ginsburg and Heintz (1966) later suggested that P. africanus should be removed from Palaeomeryx and placed it in a new genus Kenyameryx. Hamilton (1973) reviewed the material and, concluding that the Walangania gracilis and Kenyameryx africanus material represented the same taxon, combined them under the name Walangania africanus. Most researchers agree that both forms belong in Walangania, but the question of whether to maintain a specific distinction between W. gracilis and W. africanus is open. Walangania is one of the earliest ruminants in Africa, but its phylogenetic relationships remain controversial. While it traditionally has been viewed as a potential ancestor to the Bovidae, Janis and Scott (1987) and Gentry (1994) have presented evidence for a closer relationship to the Cervoidea.

The presence or absence of p1 in Walangania has been debated (Hamilton 1973; Janis and Scott 1987; Gentry 1994). If BUMP 450 is correctly referred to this species, then either p1 or dp1 was present. Similarly a bifurcated postmetconule crista has previously been considered absent from Walangania (Janis and Scott 1987, p. 31), suggesting that the Napak maxilla BUMP 274 has been misidentified. Its small size, concave antero-lingual P3 crest, posteriorly directed postprotocrista, and minute entostyles preclude reference of the Napak maxilla to Propalaeoryx austroafricanus, but since the upper dentition of the East African species P. nyanzae is hardly known, it is possible that BUMP 274 represents it. This seems unlikely, however, given the difference in size.

Genus Bugtimeryx Ginsburg, Morales, Soria, 2001

Small pecoran (m2-m3 length: ~ 2.5 to 3.4 cm depending on species). Frontal appendages unknown. Molars brachyodont with finely rugose enamel. Anterior crest of p4 bifurcated with paraconid and parastylid turned lingually, strong labial incision, oblique entoconid, and transverse entostylid. Metaconid of p4 tall, rounded posteriorly. Lower molars with protoconid and hypoconid slightly oblique and compressed. Posterior median valley open until late in wear, diminutive metastylid situated lingual to the posterior end of the postmetacrista, “Palaeomeryx‑fold” very faint. Upper molars with large metaconules. Paracone with strong labial rib, metacone with weak rib. Parastyle large, metastyle distinct. Subsidiary crests present in the anterior fossette and separate from labially directed postprotocrista and premetaconule crista. Postmetaconule crista with bifurcation. Minute entostyle and low lingual cingulum on posterior of protocone. Limbs of advanced pecoran type.

Bugtimeryx pilgrimi Ginsburg, Morales, Soria, 2001

Smallest species of Bugtimeryx (m2-m3 length: ~ 2.5 to 3.0 cm); “Palaeomeryx‑fold” moderate, stronger on m2 than on m3 (modified from Ginsburg et al. 2001).

Locality Z 127: Z 269, left mandible with dp4‑m1; Z 270, right mandible with m3; Z 2021, complete right astragalus; Z 2022, distal right metacarpal; Z 2023, right distal tibia; Z 2024, right mandible fragment with m2 and anterior of erupting m3; Z 2026, right mandible fragment with m1 and erupting m2; Z 2027, right maxilla fragment with DP4, M1, and erupting M2; Z 2028, left maxilla fragment with M1, M2, and a fragment of M3 in crypt; Z 2029, left maxilla fragment with indeterminate molar; Z 2030, left mandible with m1; Z 2032, right mandible with anterior of m3; Z 2034, right slightly damaged astragalus; Z 2035, left damaged astragalus; Z 2038, right complete magnum‑trapezoid; Z 2084, right complete scaphoid; Z 2086, incomplete distal phalanx; Z 2087, incomplete epiphysis of a proximal phalanx.

Locality Z 129: Z 228, right astragalus.

Locality Z 133: Z 175, incomplete and very battered left calcaneum.

Locality Z 151: Z 2057, distal metapodial (probably a metacarpal); Z 2068, right mandible with p4 and anterior of m1.

Locality Z 155: Z 2081, damaged left astragalus.

There are at least four and perhaps as many as five different individuals represented among the dental remains from Locality Z 127. Only two are fully adult, with erupted and worn m3s. The three astragali appear to come from three different but fully grown individuals, suggesting that at least three adults and either three or four juveniles are represented.

Localities Z 127, Z 151, and Z 155 are all in the upper part of the Chitarwata Formation, with estimated ages of 24 to 23 Ma (Lindsay et al. this issue).

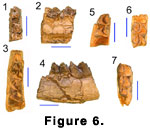

Lower Dentition. The p4 appears to have

been about the same length as the m1, although in the only specimen with both

teeth preserved (Z 2068) (Figure 6.1-6.2) the m1 is broken at the rear, making

its length unmeasurable. The worn and fractured p4 of Z 2068 has a strong labial

incision separating a large, centrally situated protoconid from a compressed

heel. The laterally directed metaconid is as tall as the protoconid and

terminates in a large distinct cusp with an anteroposteriorly elongated oval

wear figure and rounded posterior. The short anterior crest curves sharply

lingually and has a bifurcated end with both the paraconid and parastylid being

directed lingually. The entoconid is set at an oblique angle to the long axis of

the tooth, while the large entostylid is transverse. The basin between these two

cusps is closed lingually.

Lower Dentition. The p4 appears to have

been about the same length as the m1, although in the only specimen with both

teeth preserved (Z 2068) (Figure 6.1-6.2) the m1 is broken at the rear, making

its length unmeasurable. The worn and fractured p4 of Z 2068 has a strong labial

incision separating a large, centrally situated protoconid from a compressed

heel. The laterally directed metaconid is as tall as the protoconid and

terminates in a large distinct cusp with an anteroposteriorly elongated oval

wear figure and rounded posterior. The short anterior crest curves sharply

lingually and has a bifurcated end with both the paraconid and parastylid being

directed lingually. The entoconid is set at an oblique angle to the long axis of

the tooth, while the large entostylid is transverse. The basin between these two

cusps is closed lingually.

The lower molars are brachyodont (Figure 6.3-6.7), with fine vertical striations in the enamel. The metaconid and entoconid are situated slightly oblique to the long axis of the tooth and, while flattened labially, retain a more convex lingual face. The protoconid and hypoconid are distinctly selenodont. The premetacristid contacts the anterolabial end of the preprotocristid, but posteriorly the median valley is narrowly open until late in wear. With slight wear the postmetacristid connects with the postprotocristid, and these subsequently connect with the preentocristid. The prehypocristid, however, remains separate even after considerable wear (Z 270, Z 2032). The lightly worn teeth (Z 269, Z 2024, Z 2030) have very faint vestiges of a “Palaeomeryx‑fold,” whereas the more worn teeth appear to lack them. Where preserved, the metastylid is distinct but very small. It is closely appressed to the metaconid and situated just lingual to the descending trace of the postmetacristid. The m3’s have a small entostylid. All the molars have strong, low ectostylids and anterior and posterior basal cingula.

Only Z 270 preserves the posterior part of m3. It comprises a large crescent-shaped hypoconulid the antero-labial end of which contacts the postero-lingual end of the posthypocristid. There is a small, separate entoconulid (seen also on the broken m3 of Z 2032) with a posterior extension that together with the entostylid fills the gap between the postentocristid and lingual end of the hypoconulid crescent, making the lingual wall complete.

The broken dp4 of Z 269 is molariform in appearance.

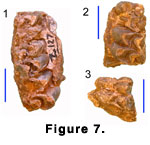

Upper Dentition. The three maxillary

fragments (Figure 7.1-7.3) are poorly preserved, with much of the enamel spalled

from the crowns of the teeth, especially labially. One maxilla (Z 2027) has what

we interpret as DP4, M1, and an erupting M2; a second (Z 2028) has the M1 and M2

preserved with a very small piece of the M3 in crypt; while the third (Z 2029)

has a worn indeterminate molar or dP4. The teeth are all low crowned with large

metaconules that produce a quadrate outline in occlusal view. Where preserved,

the parastyle and mesostyle are strong and the paracone has a strong labial rib

with a deep groove just before it. The metacone has a much weaker rib. The

postprotocrista is directed labially, as is the much longer premetaconule

crista. At the apex of the metaconule, the postmetaconule crista is posteriorly

directed, but the crista then turns sharply and runs labially to reach a much

reduced metastyle. On the indeterminate molar of Z 2029 and the M2 of Z 2027,

the postmetaconule crista has a distinct bifurcation, giving rise to a large

internal enamel spur. There is in addition a small structure filling the space

between the lingual face of the paracone and the junction of the postprotocrista

and premetaconule crista. In the unworn condition (M2 of Z 2028) the structure

is a low cross of enamel that connects the anterior face of the taller

premetaconule crista to the paracone and is clearly separate from the terminal

end of the labially directed postprotocrista. In the worn condition (M1 of Z

2028 and Z 2029) it merges with the wear traces of the postprotocrista and

premetaconule crista to form one or more small enamel fossettes, giving a

bifurcated appearance to the postprotocrista. Although heavily damaged in this

area, all the preserved molars have this structure. Finally there appears to be

a minute entostyle on the M2 of Z 2027 and, more clearly, a low cingulum that

originates between the protocone and metaconule and runs along the posterior

face of the protocone.

Upper Dentition. The three maxillary

fragments (Figure 7.1-7.3) are poorly preserved, with much of the enamel spalled

from the crowns of the teeth, especially labially. One maxilla (Z 2027) has what

we interpret as DP4, M1, and an erupting M2; a second (Z 2028) has the M1 and M2

preserved with a very small piece of the M3 in crypt; while the third (Z 2029)

has a worn indeterminate molar or dP4. The teeth are all low crowned with large

metaconules that produce a quadrate outline in occlusal view. Where preserved,

the parastyle and mesostyle are strong and the paracone has a strong labial rib

with a deep groove just before it. The metacone has a much weaker rib. The

postprotocrista is directed labially, as is the much longer premetaconule

crista. At the apex of the metaconule, the postmetaconule crista is posteriorly

directed, but the crista then turns sharply and runs labially to reach a much

reduced metastyle. On the indeterminate molar of Z 2029 and the M2 of Z 2027,

the postmetaconule crista has a distinct bifurcation, giving rise to a large

internal enamel spur. There is in addition a small structure filling the space

between the lingual face of the paracone and the junction of the postprotocrista

and premetaconule crista. In the unworn condition (M2 of Z 2028) the structure

is a low cross of enamel that connects the anterior face of the taller

premetaconule crista to the paracone and is clearly separate from the terminal

end of the labially directed postprotocrista. In the worn condition (M1 of Z

2028 and Z 2029) it merges with the wear traces of the postprotocrista and

premetaconule crista to form one or more small enamel fossettes, giving a

bifurcated appearance to the postprotocrista. Although heavily damaged in this

area, all the preserved molars have this structure. Finally there appears to be

a minute entostyle on the M2 of Z 2027 and, more clearly, a low cingulum that

originates between the protocone and metaconule and runs along the posterior

face of the protocone.

The wear and pattern of tooth eruption of the maxillas indicate they represent the remains of three different individuals.

Postcranial Remains. Tibia: Z 2023 is a poorly preserved distal portion of a tibia, in which fusion of the epiphysis to the diaphysis is incomplete. The articulation for the fibular malleolus is divided into a larger posterior portion separated from a smaller anterior one by a well-defined sulcus for the fibular spine of the malleolus. Both articular surfaces are damaged, but the posterior one is clearly concave.

Astragalus: The best preserved astragali are Z 228 and Z 2021, while the others are to varying degrees damaged. As noted by Ginsburg et al. (2001) the astragalus of Dorcabune is parallel sided as are those of advanced pecorans, making identification of either difficult. In contrast to Dorcabune, the distolateral calcaneal facet is confined to the distal edge of the astragalus, and separated from the raised lateral rim of the susentacular facet by a roughened sulcus, while the proximal lateral calcaneal facet is confined to the edge of the susentacular facet and does not extend dorsally. The cuboid condyle extends laterally, creating a distinct notch on the lateral side of the astragalus similar to what is seen in tragulids. The condyle, however, is cylindrical rather than conical as in small species of Dorcabune. The astragalus is narrow, with an approximate width to length ratio of 1:1.8.

Scaphoid: Although the color is slightly different, it is possible that Z 2084 came from the same individual as the magnum-trapezoid Z 2038. The specimen is slender when viewed from a proximal aspect and proximally-distally short for the dorsal-ventral diameter.

Magnum-trapezoid: Z 2038 is well preserved with a rectangular outline, a tall proximal keel, and a narrow lunar facet that does not expand laterally. The inferior posterior unciform facet is widely separated from the anterior unciform facet.

Metacarpals: Z 2022 is well preserved, while Z 2057 is somewhat broken and crushed, with matrix obscuring some features. In both specimens the third and fourth metacarpals are fused, with the medullary cavities separate at the level of the nutrient foramen. On the distal articular surfaces the keels extend dorsally, but are not as well developed there as they are ventrally. Consequently, in lateral view the keels are strongly asymmetrical. On each metacarpal the tubercle for the collateral ligament has a lipped rim ventrally, but the lip does not extend dorsally. As a result the dorsal external articular surface of the condyle is incomplete. In contrast, the internal articular surface extends dorsally, terminating in a small pit at the end of the shaft.

Ginsburg et al. (2001) placed Bugtimeryx in the Giraffidae without comment. However, both the type and our material shows the taxon to have a faint “Palaeomeryx‑fold.” We have, therefore, tentatively placed it in the Cervoidea.

While the low-crowned molars of Bugtimeryx can easily be distinguished from even the earliest bovids, the p4 described here is surprisingly bovid-like. Similarities include the short, compressed heel set off from the protoconid by a strong labial incision, the short, sharply turned anterior crest, and the height and distinctiveness of the metaconid. However, in early bovids (as documented by material from the Kamlial Formation of northern Pakistan) the p4 paraconid is smaller, the metaconid is separated from the protoconid by a narrow isthmus of enamel, and the entoconid is more nearly transverse. Postcranially there are also similarities and differences. Bovids have a less distinctive notch above the distolateral calcaneal facet of the astragulus, their scaphoid tends to be wider and deeper relative to the dorsal-ventral dimension, and the magnum-trapezoid has a wider articulation for the scaphoid and a lower proximal keel. Finally, while the distal metapodial keels of early bovids are asymmetrical, the external articular surface of the condyle is complete on the dorsal aspect.

Bugtimeryx differs from Namibiomeryx Morales, Soria, Pickford 1995 in being much less hypsodont, lacking precocious fusion of the prehypocristid and trigonid complex, having a bifurcated anterior crest on p4, more distinct metastylids, and a crescent-shaped m3 hypoconulid forming a continuous lingual wall.

Ginsburg et al. (2001) recorded similarities between Bugtimeryx and Andegameryx Ginsburg 1971, but noted that they differed in the presence of a larger metastylid on the lower molars of Bugtimeryx. The material described here shows they also differ greatly in p4 morphologies. Bugtimeryx can be distinguished from Walangania on the basis of the p4, which in Walangania is at best only weakly bifurcated anteriorly. Walangania also possesses larger, more distinct metastylids and in the upper molars a shorter, more posteriorly directed postprotocrista and a lingual protoconal cingulum. Many of the same characters distinguish Bugtimeryx from cervoid-like taxa such as “Gelocus” whitworthi Hamilton 1973, Bedenomeryx Jehenne 1988 or Pomelomeryx Ginsburg and Morales 1989, which typically also have a stronger “Palaeomeryx‑fold” (Ginsburg et al. 1994).

Small, primitive giraffoids such as Propalaeoryx bear a general resemblance to Bugtimeryx but are about 20 to 30% larger. In Propalaeoryx the p4 is relatively long, with an oblique entostylid and an elongated metaconid. In addition, its lower molars have more separated and lingual metastylids, while the medial valley is open posteriorly (Janis and Scott 1987; Morales et al. 1999).

Dremotherium Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire 1833 and Amphitragulus Pomel 1846 are dentally very similar to Bugtimeryx, particularly in the structure of the p4 with a bifurcated anterior crest bent sharply to the lingual side combined with a short heel, oblique entoconid, and large metaconid (Janis and Scott 1987; Ginsburg et al. 1994). Amphitragulus has, in addition, an m3 with a strong connection between the posthypocristid and entoconid and a posteriorly extended entoconid. Amphitragulus and Dremotherium, however, have a well-developed “Palaeomeryx‑fold” and in the upper molars a more posteriorly directed postprotocrista, salient cingulae on the upper molars, and in the case of Amphitragulus a simple postmetaconule crista.

Ginsburg et al. (2001) based Bugtimeryx pilgrimi on a mandible with m2 and m3, and referred an upper molar (PAK 2490) and several postcranial elements to the species. The cruciate protocone and lingual cingulum of the upper molar suggest to us that the referred upper molar belongs to a species of Dorcabune, mostly likely Dorcabune sindiense Pilgrim 1915.

As envisaged by Ginsburg et al. (2001) Bugtimeryx had three species: 1) the genotype Bugtimeryx pilgrimi; 2) Bugtimeryx beatrix (Pilgrim 1912), founded on a single mandible with m2-m3 and questionably referred to Prodremotherium by Pilgrim (1912); and 3) Bugtimeryx gajensis (Pilgrim 1912), also based on a single mandible with m1-m2 and initially questionably referred to Gelocus (Pilgrim 1912). The three species were diagnosed by Ginsburg et al. (2001) as being different in size. Only B. gajensis has distinctive morphological features. The type and referred material of B. pilgrimi came from what are thought to be Early Miocene levels of the Chitarwata Formation at Dera Bugti (Welcomme et al. 2001). Both of Pilgrim’s specimens also came from deposits near Dera Bugti, from what he called the “base of the Gaj" (Pilgrim 1912, caption to plate XXV). In his use of “Gaj,” Pilgrim was referring to what is now called the Chitarwata Formation (Downing et al. 1993), and it seems likely that Pilgrim’s specimens came from the lowest fossiliferous levels at Dera Bugti. If so, they could be as old as Early Oligocene (Welcomme et al. 2001).

B. pilgrimi and B. beatrix differ solely in size. The material described here is intermediate in size between the two, and we strongly suspect the fossils all belong to a single species. However, we have chosen to refer our material to B. pilgrimi because of the possible great differences in age between the types of B. pilgrimi and B. beatrix, and because as a taxon, B. pilgrimi is currently better known. “Bugtimeryx” gajensis is a significantly larger species, and if material recently collected from the lower unit of the Chitarwata Formation at Zinda Pir and described in the preceding belongs to the same species, then it represents a different genus.

Our concept of Bugtimeryx relies greatly on the morphology of the p4 from locality Z 151, and thus our reference of that material to the taxon is critical to many of the conclusions we reach. However, the fossils from locality Z 151 are considerably older stratigraphically than the other Zinda Pir material described here and could belong to a different taxon. If so, then the distinctions we make between Bugtimeryx and other taxa are more problematic.

Genus and Species Indeterminate

Locality Z 127: Z 2031, fragment of a right mandible with m1(?); Z 2033, lingual half of a very worn left upper molar.

Known from only one site, Locality Z 127 in the upper part of the Chitarwata Formation. It is approximately 23 Ma in age (Lindsay et al. this issue).

The mandible (Figure 8.1 - 8.2) has a single,

moderately worn tooth, which because of the dentary’s shape we believe to be an

m1. The tooth is brachyodont, with metaconid and entoconid slightly oblique to

the long axis of the tooth, flattened labially, and convex lingually. Both

protoconid and hypoconid are selenodont. The premetacristid contacts the

anterolabial end of the preprotocristid, while the posthypocristid contacts a

small entostylid to close the posterolingual end of the median valley. The

prehypoconid is isolated, but a small secondary spur of the preentocristid

contacts its anterior tip. There is a very subdued “Palaeomeryx‑fold.”

The metastylid is small and situated well forward of the descending trace of the

premetacristid. The molar has a low ectostylid as well as anterior and posterior

basal cingula.

The mandible (Figure 8.1 - 8.2) has a single,

moderately worn tooth, which because of the dentary’s shape we believe to be an

m1. The tooth is brachyodont, with metaconid and entoconid slightly oblique to

the long axis of the tooth, flattened labially, and convex lingually. Both

protoconid and hypoconid are selenodont. The premetacristid contacts the

anterolabial end of the preprotocristid, while the posthypocristid contacts a

small entostylid to close the posterolingual end of the median valley. The

prehypoconid is isolated, but a small secondary spur of the preentocristid

contacts its anterior tip. There is a very subdued “Palaeomeryx‑fold.”

The metastylid is small and situated well forward of the descending trace of the

premetacristid. The molar has a low ectostylid as well as anterior and posterior

basal cingula.

The upper molar is a very heavily worn lingual half of a tooth. It has a minute entostyle on the anterior face of the metaconule and a low cingulum along the posterior face of the protocone.

The teeth of this taxon are too small to belong to Progiraffa exigua and too large for ?Gelocus gagensis or any species of Bugtimeryx. They are, in addition, appreciably older than the material referred to Progiraffa exigua. The presence of an accessory connection between the preentocristid and prehypocristid is unusual but has been reported in Oriomeryx Ginsburg 1985 (Ginsburg et al. 1994). That taxon, however, has a strong “Palaeomeryx‑fold” and upper molars without a lingual cingulum.