|

|

|

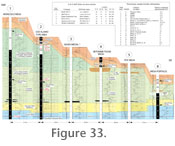

NW TO SE THINNING OF CRETACEOUS STRATA IN SW SAN JUAN BASINFigure 1 shows that the Fruitland Formation-Kirtland Formation interval thins by 2,100 feet (640 m) from the northwestern to the southeastern part of the San Juan Basin. This interval also thins dramatically in the southern part of the basin from Moncisco Mesa to Mesa Portales. The isopach map (Figure 1.1) of the interval between the Huerfanito Bentonite Bed and the base of the Ojo Alamo Sandstone shows thinning of this interval of about 1,000 feet (300 m) between these two localities. To better understand and illustrate the nature of this thinning, northwest-trending stratigraphic and time-stratigraphic cross sections (Figure 33, Figure 34, and Figure 35) were constructed across the southern part of the basin to illustrate the stratigraphy of the interval from the uppermost part of the Upper Cretaceous Lewis Shale to the lowermost part of the lower-Paleocene Nacimiento Formation; the line of these cross sections is shown on Figure 3. (Note: The following discussion of these cross sections uses feet, followed by the parenthetical thicknesses in meters, because the depth track for the geophysical logs referred to are calibrated in feet.)

The locations of five of the six geophysical logs on the stratigraphic cross section (Figure 33) were selected close to important outcrop localities in the southwestern San Juan Basin where paleomagnetic, palynologic, and fossil-vertebrate data were obtained. The log of drill-hole 3 was inserted in the section to maintain even spacing of subsurface control along the line of section. The datum for this cross section is the Huerfanito Bentonite Bed of the Lewis Shale. Because the Huerfanito Bed is an altered volcanic ash bed that represents an ash fall into the Lewis-Shale sea in Late Cretaceous (Campanian) time, this marker bed represents a time horizon throughout the San Juan Basin. The Huerfanito Bed is an easily recognizable marker bed on geophysical logs in the subsurface throughout most of the San Juan Basin. Radiometric ages of sanidine crystals from the altered volcanic ash beds shown on Figure 32 and Figure 33 were acquired using 40Ar/39Ar methodology (Fassett and Steiner 1997, Fassett et al. 1997, Fassett 2000). Four of these ages are projected into the log of drill-hole 2 of Figure 33 from their outcrop locations in or near Hunter Wash, about 9 km to the southwest. Magnetochrons identified near drill holes 1, 2, 4, and 6 (discussed in detail above) have also been projected into the geophysical logs. The magnetic-polarity column of drill-hole 2 is a composite of the two (virtually identical) columns of Lindsay et al. (1981) and Fassett and Steiner (1997) of Figure 18. The magnetic-polarity column at drill-hole 6 is from Mesa Portales (Figure 23). The nearby Eagle Mesa magnetic-polarity column of Butler and Lindsay (1985) depicted on Figure 28 and Figure 29 places the C33n-C32r reversal at virtually the same level as at Mesa Portales. The levels of palynologic samples collected from nearby outcrop localities are shown on drill-hole logs 1, 2, 5, and 6; the palynology of these strata is summarized in the "Palynology" section of this report and is discussed in greater detail in Appendix. Dinosaur- and mammal-bone localities shown in the Ojo Alamo Sandstone at drill holes 2 and 4 are at nearby outcrops and are discussed in the "Vertebrate Paleontology" section of this report. The lowest unit shown on the stratigraphic cross section of Figure 33, the Lewis Shale, was deposited as marine muds and silts on the western edge of the Western Interior Seaway in late Campanian time. Overlying the Lewis Shale is the Pictured Cliffs Sandstone, a time-transgressive, shoreface-marine sandstone, deposited during the final regression of the Western Interior Seaway from southwest to northeast across the San Juan Basin area. The fact that the top of the Pictured Cliffs is essentially parallel to the Huerfanito Bentonite Bed on the logs of drill holes 1 through 5 (Figure 33) indicates that the line of cross section is directly along the depositional strike or paleoshoreline of the Pictured Cliffs sea. Between holes 5 and 6, the Pictured Cliffs is seen to rise stratigraphically; this is because the trend of the line of section between these two holes is eastward, diverging from the Pictured Cliffs shoreline's southeast trend, and is thus reflecting the northeastward stratigraphic rise of the Pictured Cliffs Sandstone. The 400 m stratigraphic rise of the Pictured Cliffs across the entire San Juan Basin is illustrated on Figure 32. The thickness of the Fruitland Formation ranges from about 300 feet (90 m) in drill hole 3 to 400 feet (120 m) in drill hole 1 on this cross section. The Fruitland-Kirtland contact is virtually parallel to the top of the Pictured Cliffs in drill holes 1 through 5 (Figure 33). Coal beds, representing back-shore swamp deposits in the lower Fruitland Formation, are present in all six drill holes. The contact of the lower shale member of the Kirtland Formation and the Farmington Sandstone Member of the Kirtland is about 600 feet (180 m) above the top of the Pictured Cliffs in holes 1 through 3, however in holes 4 through 6, the Farmington Sandstone is absent and large channel sandstones appear in the upper part of the section. Above the Farmington Sandstone and upper shale member of the Kirtland Formation, undivided, the Ojo Alamo Sandstone is seen to be stepping down from drill hole 1 to drill hole 6; the base of the Ojo Alamo is 950 feet (290 m) lower in drill hole 6 than in drill hole 1. All of this thinning is apparently at the expense of the underlying Kirtland Formation, which appears to be totally cut out in drill hole 6. There is a problem with the simple interpretation of the geophysical-log section depicted on Figure 33, apparently showing progressive truncation of the Fruitland-Kirtland interval from northwest to southeast. Note that the polarity reversal from C33n to C32r (within the Fruitland-Kirtland interval) is also stepping down from drill hole 1 to drill hole 2, and from drill hole 2 to drill hole 6 (Figure 33). Paleomagnetic reversals are isochrons, therefore, if deposition of the Fruitland-Kirtland interval strata had been continuous and even across the area of the Figure 33 cross section, the C33n-C32r reversal would be parallel with the underlying Huerfanito Bentonite Bed isochron. If the progressive truncation of Kirtland strata from northwest to southeast were as simple as apparently shown on Figure 32, resulting only from a pre-Ojo-Alamo-Sandstone erosion cycle, that truncation would have totally cut out magnetochron C32r and several hundred feet (about 200 m) of the upper part of chron C33n in drill hole 6, which is clearly not the case. Why then is the C33n-C32r reversal present in the Mesa Portales area? There is an elegant, straightforward solution to this problem.

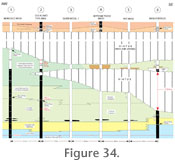

The stratigraphic level of the unconformity within the Fruitland-Kirtland interval is not known with certainty, because it has never been discovered on the outcrop and it cannot be detected on geophysical logs. In drill hole 6 (Figure

34), the unconformity has to be below the top of chron C33n and above the coal bed in the lower part of the Fruitland. Because the top of C33n is within the prominent white sandstone bed at Mesa Portales (Figures 22, 23), a reasonable placement is at the base of the white sandstone (Figure 33,

Figure 34, and

Figure 35).

Figure 35 is a time-stratigraphic cross section along the same line of section as Figure 33 and Figure 34, but with the vertical exaggeration changed from 130 X to 85 X to make possible the portrayal of the 7.8-m.y. hiatus separating Campanian Kirtland Formation strata from the overlying Paleocene Ojo Alamo Sandstone strata. The age of the base of the Ojo Alamo Sandstone is estimated to be 65.2 Ma based on an age of 65.112 Ma (Gradstein et al. 2004) for the base of magnetochron C29n located just above the base of the Ojo Alamo. Palynologic data also confirm that earliest Paleocene strata are absent in the San Juan Basin (Newman 1987, p. 158). In addition, the K-T boundary asteroid-impact fall-out layer or the iridium-enriched layer found at the K-T boundary at many localities in the Western Interior of North America, have not been found at or near the K-T interface in the San Juan Basin despite concerted attempts to locate them at several localities in the southern San Juan Basin (Orth et al. 1982). It is thus estimated that about 0.3 m.y. of earliest Paleocene time is not represented by rock strata in the southern San Juan Basin (Figure 35). Palynologic data (discussed below) support the absence of lowermost Paleocene strata below the base of the Ojo Alamo Sandstone. |

|

Figure

34

Figure

34