Eternal Loving Embrace of Two Eocene Moths

Eternal Loving Embrace of Two Eocene Moths

For the average person, insects trapped in amber may spark images from the film Jurassic Park, where mosquitos were the key to resurrecting living dinosaurs. Although collecting dino DNA from fossil insects may not be feasible, there is still much to learn from these specimens frozen in time.

Dr. Thilo C. Fischer and Dr. Marie K. Hörnig are passionate palaeoentomologists (the study of fossil insects) and are beyond excited to share their fascinating discovery with the world! Not only did they find two individual moths (Order: Lepidoptera) trapped together in Baltic amber dating back 56-33 million years ago (Eocene), but they were a mating pair in copula! This is an extremely rare finding for any insect group and a first for the group Lepidoptera.

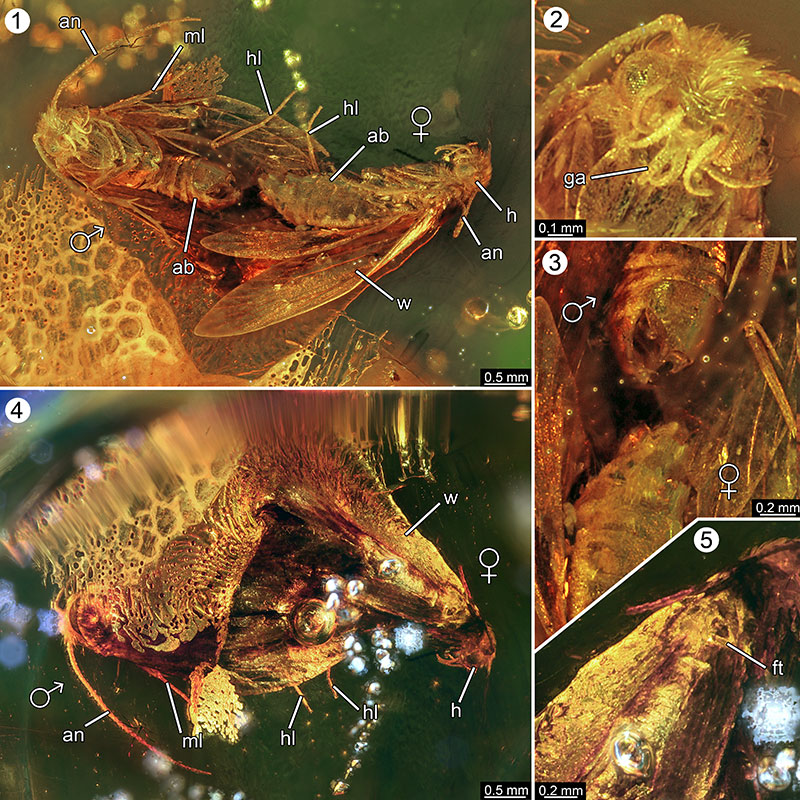

Mating Teneid moths found in Baltic amber dating back to the Eocene (56-33.9 Ma).

Mating Teneid moths found in Baltic amber dating back to the Eocene (56-33.9 Ma).

“Butterflies and moths have scales on their wings, this is where the name Lepidoptera is from” says Dr. Fischer. If you’re curious, the root words of Lepidoptera are “lepido” meaning scale and “ptera” for wings, being Greek in origin.

“However, scales may occur in other insects too. For fossil moths it may even be difficult to identify the family to which they belong. Some have characters which can be recognized easily, but often the distinctive traits (apomorphies) are not easily identified. And even with the nice preservation in amber many characters like details of genital structure cannot be studied at all. Some traits may be hidden below scales” explains Dr. Fischer.

For many insects, including moths, physical characteristics help to identify the species. “Insects show a fascinating diversity, where the closer you look the more you will observe and understand” exclaims Dr. Fischer. What makes this find even more exceptional is that not only can they identify a new species but having both a male and female moth present allows a unique study between sexes of the same species.

This is extremely rare. “Such fossil mating events have been found with other insect orders, in Baltic amber most often with flies and midges, but to the best of our knowledge this has never been found for Lepidoptera. Not even from other ambers, or from sediments where fossil insects are found” says Dr. Fischer. Such finds can preserve life-like conditions or even actions. Dr. Hörnig explains “if insects were captured during mating, it is in addition a great opportunity to investigate the morphology of male and female of the same species, which can be otherwise difficult in fossil species, especially if there is a strong sexual dimorphism.”

Sexual dimorphisms, or the differences in physical appearance between sexes of the same species, can help infer how individuals of the same species interacted with each other. From this discovery, the male moth has more developed eyes and antennas compared to the female, indicating that the female attracts the male i.e. with pheromones. This is common for many living moth species but is not always the case. Although they were not able to identify any obvious pheromone spreading organs, Dr. Fischer explains that “for many extant species some peculiar scales serving this purpose can be observed, for others such structures are quite inconspicuous.”

Moths in Baltic amber with sexual dimorphisms highlighted.

Moths in Baltic amber with sexual dimorphisms highlighted.

This is also what attracted Dr. Hörnig to this specimen since her research is primarily focused on the reconstruction of behavioral aspects of extinct arthropods (which includes insects) based on fossils. It can be difficult to piece together the behavior for insects, especially when studying fossils. Therefore “every finding in this context is an important piece for a better understanding of the evolution of the variety of sophisticated lifestyles of insects, which we can observe today” says Dr. Hörnig.

“Lepidoptera have most delicate and beautiful structures, it is one of the four largest insect orders with respect to species numbers. Studying fossil forms in paleontology adds a brief glimpse on deep time” states Dr. Fischer. Being able to study insects from Eocene Baltic amber, which once represented a warm subtropical climate, provides insights into the history of certain insect groups which are almost entirely restricted to tropical environments today. Dr. Hörnig explains “as we cannot observe behavior of extinct species directly, we can still discuss most probable scenarios, based on observations of both fossils and species living today.”

Not only is this discovery exciting being the first of its kind, but it is also bridging the gaps between insect interaction and behavior millions of years in the making! You can delve into the deeper details from the original article here.