It was a fearsome predator that filled the oceans with fear. It was a shadow; a phantom from the depths that eluded the watchful crab, the anxious guppy until… it was too late! It was a prowler. A monster! A marine horror that menaced its fellow denizens of the deep as a living, breathing nightmare! It was…

...

...

...

...

... A baby shark?

... Doo-doo-doo?

For some animals, especially animals that scare us, it can sometimes be easy to forget that they did not begin life as full-fledged adults. Whether it’s because the adults represent power (like sharks and crocodiles) or inspire a sense of awe or majesty (like elephants or whales), one can sometimes forget that adult creatures that evoke those feelings are not necessarily the “real” or “proper” version of that animal, but only one part of a whole life cycle. Which brings us back to baby sharks.

While many modern species of sharks spend their lives prowling the open ocean as adults, baby sharks, or pups, live nearer the shore in safer, shallower waters. Here, they can feed and grow in the relative safety of the shallows away from greedy eyes and open mouths of their adult counterparts. Journeying back in the recent geologic past, one finds examples of extinct sharks engaging in similar behaviors. Megalodon, star of the silver screen and deep ocean conspiracy theories, very likely left their young in shark nurseries, based on fossil evidence. Direct fossil evidence, preserved shark nurseries, provide a strong indication that prehistoric sharks grew up in the shallows, away from adults, just like many modern sharks. That all prehistoric sharks engaged in this behavior, however, is not necessarily a given. A recent paper in Palaeontologia Electronica finds strong evidence of a shark nursery from Oligocene South Carolina (23-25 Ma). The shark in question is Carcharocles angustidens. C. angustidens is an early relative of megalodon (Carcharocles megalodon). Both sharks were the top dog (or fish) of their day, and both, based on fossil evidence, grew up in nurseries.

Bringing Up Baby

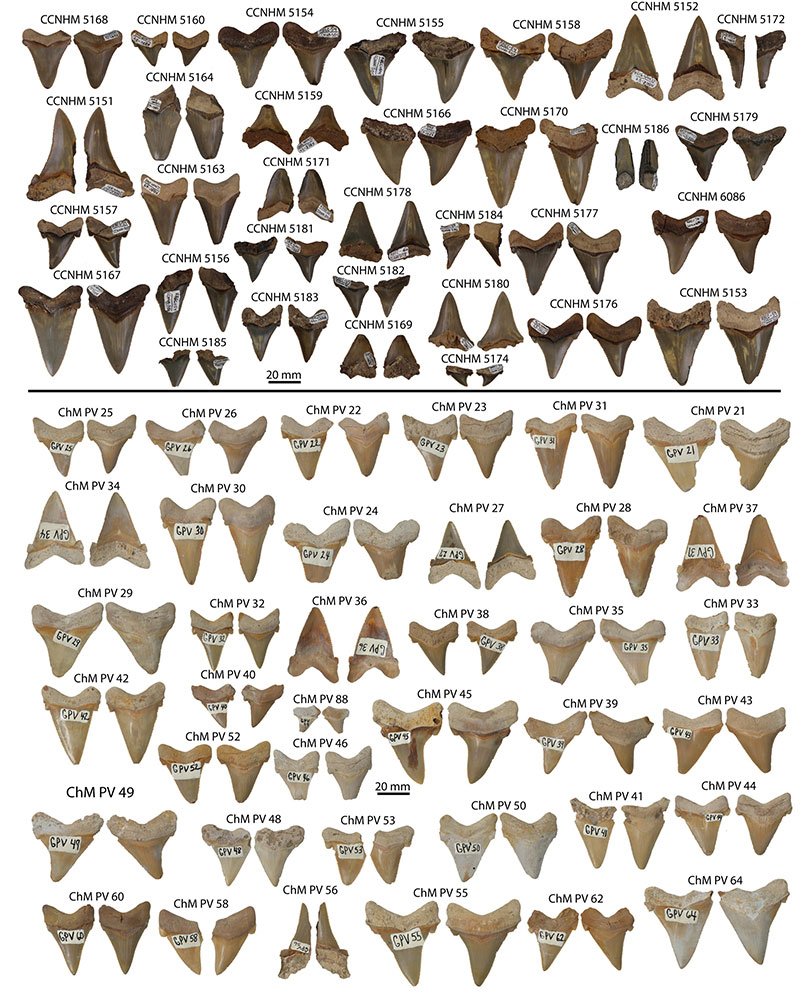

Figure 1. Teeth of Carcharocles angustidens from Oligocene South Carolina

Figure 1. Teeth of Carcharocles angustidens from Oligocene South Carolina

25 million years ago, the land around Charleston, South Carolina represented a shallow-water embayment. The area was rich in prehistoric marine life, from early whales to sea turtles to a whole myriad of fishes. The embayment was isolated, protected from the prowling stomachs of adult sharks. Here might be the perfect spot for a young shark to grow up. In 1996, while examining the site, Dr. Robert Purdy certainly thought so. Purdy suggested that the site might represent a shark nursery in Oligocene South Carolina. Fast forward two decades and researchers from College of Charleston have set about to re-examine Purdy’s shark nursery hypothesis and determine whether or not the Charleston embayment really was an ancient refuge for baby sharks. Making such a determination is not without its complications. The upside? The fossil site is rich in shark teeth. The hitch? Shark skeletons, being made of cartilage, very rarely preserve. So how does one determine the size of a shark’s whole body from only a set of scattered teeth?

As it turns out, estimating shark body size from teeth is not a new problem, nor does it require an entirely new solution. Another recent paper published in Palaeontologia Electronica uses teeth to investigate shark body size. By comparing the size of modern sharks (that are ecologically similar to the study animal) with the size of their teeth, researchers can determine what kind of mathematical relationship exists between the size of shark bodies and teeth and then apply what they have learned about that relationship to prehistoric shark teeth.

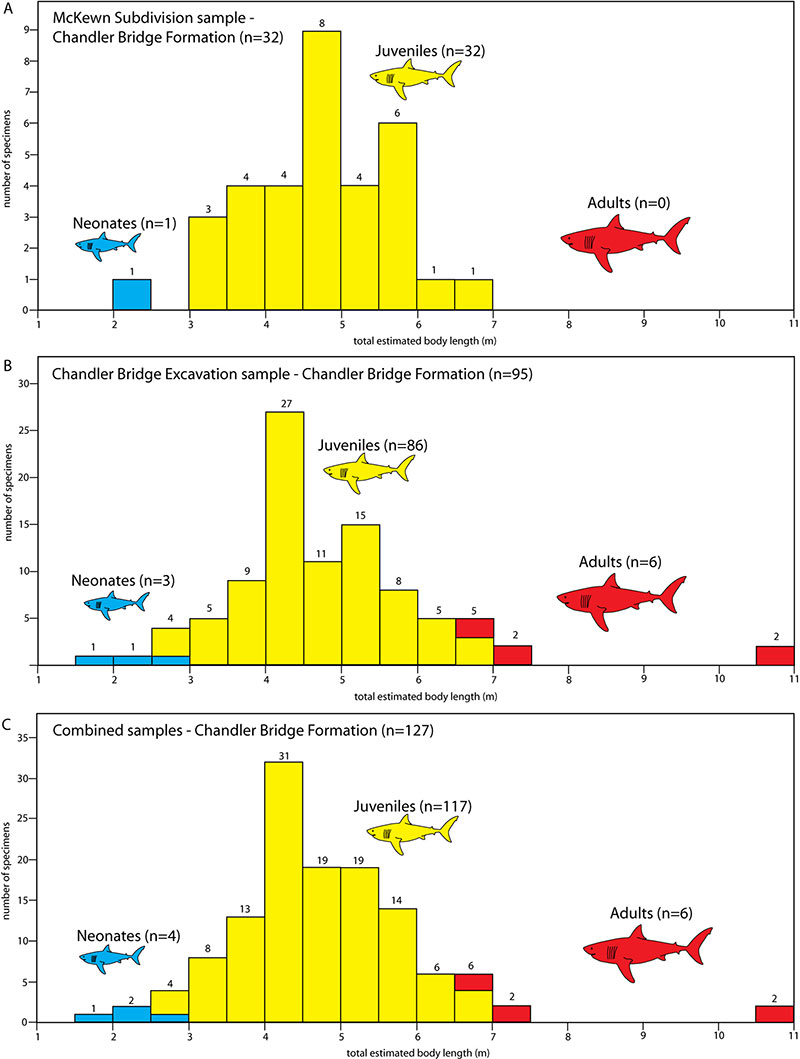

Using this method, researchers from the College of Charleston estimated the body sizes of more than 127 shark teeth found at the Charleston embayment. Of the 127 teeth present at the site, researchers found that 117 of them came from juvenile sharks, between 1.5 and 6.5 meters in length. Only 9 of the 127 total shark teeth likely came from adult animals (the remaining sharks were smaller than juveniles, categorized as neonates). A much smaller sample of shark teeth also showed an overwhelming presence of juvenile sharks in the underlying rock layer.

Shark teeth are quite popular among amateur fossil collectors, with collectors favoring large and impressive specimens over small or fragmentary ones. To ensure that their study actually measured the prevalence of large versus small sharks, the researchers took special precautions. Dr. Boessnecker, one of the researchers on the study, elaborates, “Shark teeth are incredibly common, but great care is needed in order to make discoveries like this: we were only able to do this study because there was no interference or cherry picking.” To combat “cherry picking”, the researchers took special care to make sure what they were collecting was not merely “leftovers” after collectors had picked the sites clean of all large shark teeth by gaining exclusive permission from private landowners to collect at the site.

Figure 2. Teeth from juvenile sharks dominant the collections from the Charleston Embayment.

Figure 2. Teeth from juvenile sharks dominant the collections from the Charleston Embayment.

Small teeth, however, are not necessarily enough to declare the Charleston Embayment an ancient shark nursery. Previous research has suggested three criteria a site must fulfill to be considered a likely nursery. The presence of mostly young sharks is one such criterion as well as the presence of ample prey and a shallow, protective environment. The Charleston Embayment checks all three of these boxes. That the area was prey-rich and shallow has been known since 1997. Now that the current researchers have determined that most of the sharks here were indeed juveniles, the evidence overwhelmingly points to the presence of a shark nursery some 25 million years ago.

Though not quite as large as the younger and more famous megalodon, Carcharocles angustidens was quite a large shark, with the largest specimens estimated to be larger than modern great whites. Pups of the species were also no guppies. Despite their larger size as adults, this study suggests that C. angustidens was not so dissimilar to modern sharks in terms of its life cycle. Dr. Boessnecker further explains, “[The presence of juvenile sharks at the Charleston Embayment] tells us that despite their gigantic size, megatoothed sharks faced some of the same problems that modern sharks do during their growth. This further suggests that the Charleston Embayment was relatively safe for enormous baby sharks 25 million years ago.”

Indeed, not far from the former site of the nursery where C. angustidens pups swam, hunted, and grew, is a modern shark nursery - just off the South Carolina coast. Here, pups of Carcharhinus, Rhizoprionodon, Mustelus, and Sphyrna also swim, hunt, and grow - just as Carcharocles angustidens did 25 million years earlier.

To read more about this study, you can find the original article here.