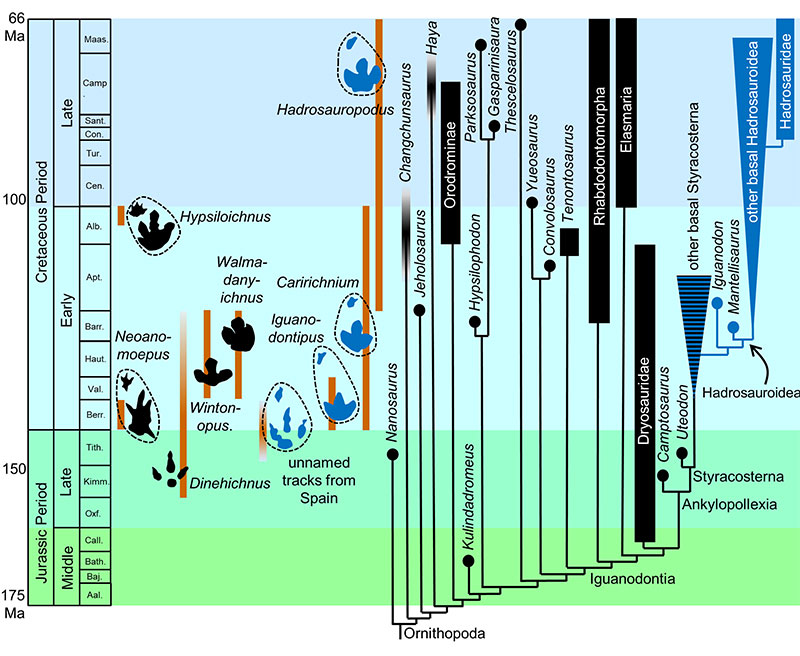

FIGURE 1. Right pectoral girdle and forelimb bones of the holotype of Styracosaurus albertensis (CMN 344) and motion at the shoulder. A. Right scapula and coracoid in lateral view. B-D. Humerus in lateral (B), posterior (C), and anterior (D) views, with broken white line indicating edge of humeral head. E-F. Radius and ulna in proximal (E) and distal (F) views. G. Range of parasagittal motion at the shoulder in lateral view. H. Range of motion at the shoulder in dorsal view. I. Range of transverse motion at the shoulder in anterior view, with radius and ulna included; the broken line indicates the humerus in the approximate position of full elevation through the transverse plane, and the unbroken line indicates the humerus in the position that was used for photographing it in position 3. J. Range of parasagittal and transverse motion at the shoulder in lateral view, with radius and ulna included. K-M. Fleshed out reconstructions of S. albertensis in anterior view in habitual posture for standing and locomotion (K), in anterior view with forelimbs in sprawling posture (L), and in lateral view with forelimbs in habitual posture for standing and locomotion (M). 1 - 3, positions 1 - 3 (see Materials and Methods for description), c, coracoid; g, glenoid cavity; h, humerus; hh, humeral head; r, radius; s, scapula; u, ulna.

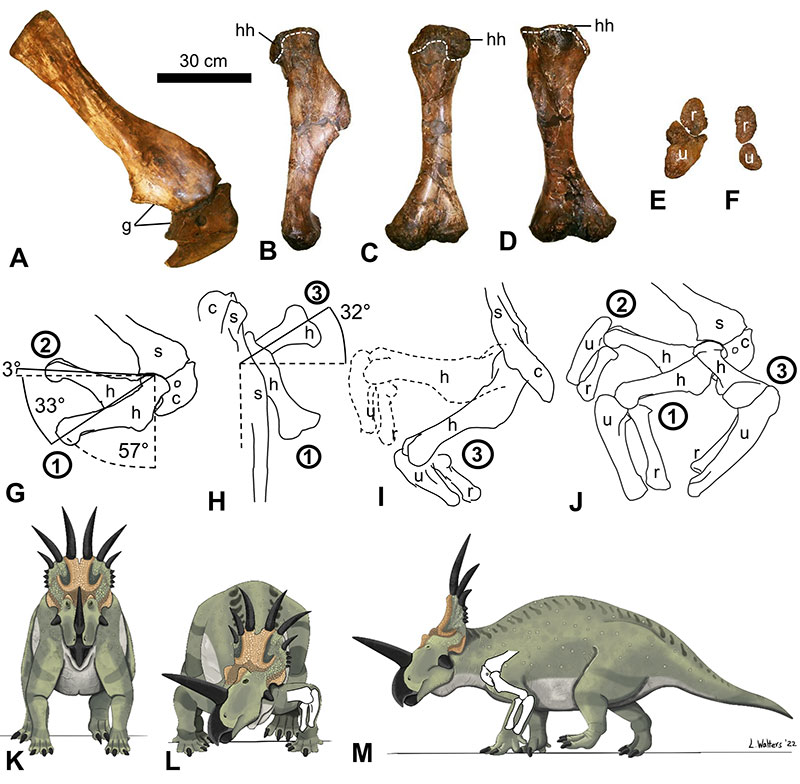

FIGURE 2. Right pectoral girdle and forelimb bones of Thescelosaurus sp. (NCSM 15728) and motion at the shoulder. A. Right scapulocoracoid in lateral view. B-D. Humerus in lateral (B), posterior (C), and anterior (D) views, with broken white line indicating edge of humeral head. E-F. Radius and ulna in proximal (E) and medial (F) views. G. Motion at the shoulder in lateral view. H. Transverse motion at the shoulder in anterior view. I-J, Skeletons of Thescelosaurus sp. NCSM 15728 (I) and CMN 8537 (J), showing that the curvature of the anterior dorsal vertebrae positions the forelimb such that it can reach the ground when the sacrum is horizontal. K, Tracing of several of the bones of CMN 8537 (vertebral centra, femur, tibia + fibula + proximal tarsals, metatarsus + distal tarsal, scapulocoracoid, humerus, radius + ulna, and carpus + metacarpus), with corrections of the dislocations at the hip and posterior dorsum in the preserved skeleton, and with heavy lines representing the long axis of the sacrum and the surface of the ground, showing that the forelimb can reach the ground and can also be retracted to avoid the ground during bipedal locomotion. L, Fleshed-out reconstruction of Thescelosaurus sp. posed as in K. 1-3, positions 1-3 (see Materials and Methods for description), c, coracoid; ca, carpals; g, glenoid cavity; h, humerus; hh, humeral head; r, radius; s, scapula; u, ulna.

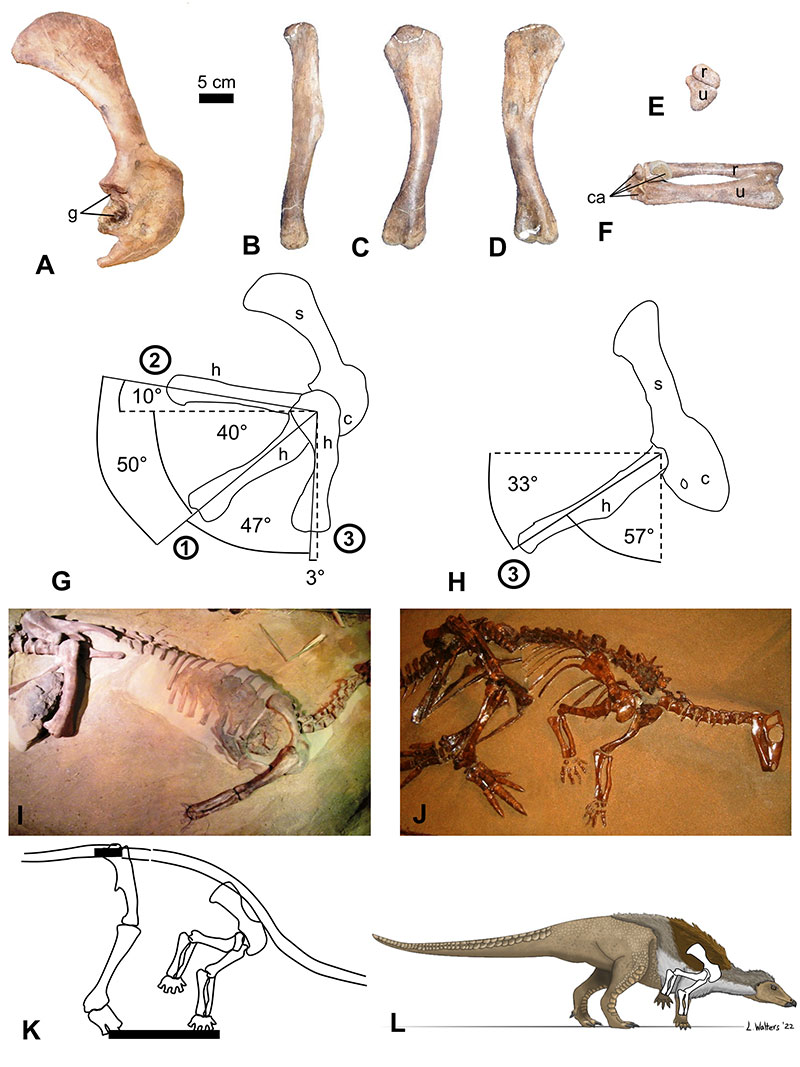

FIGURE 3. Stratigraphic distribution of ornithopod and basal ornithischian ichnogenera (after Lockley et al., 2003, 2009; Stanford et al., 2004; Díaz-Martínez et al., 2015; Salisbury et al., 2016), with time-calibrated phylogeny of Ornithopoda (after McDonald, 2012; Dieudonné et al., 2020; Kobayashi et al., 2021). Blue parts of the cladogram and blue manus and pes prints indicate taxa and ichnotaxa with manus enclosed in a mitten-like sheath of soft tissue. Striped blue and black on the cladogram indicates uncertainty: known fossils don’t include enough of the manus to determine whether the fingers were enclosed in a mitten-like sheath of soft tissue. The unnamed tracks from Spain are those described by Pérez-Lorente et al. (1997).