Unlocking the secrets of the thylacine: The skeletal atlas of an iconic marsupial

Unlocking the secrets of the thylacine: The skeletal atlas of an iconic marsupial

The thylacine (Thylacinus cynocephalus), sometimes referred to as a Tasmanian tiger (due to the striped pattern on its back) or the Tasmania wolf (due to the dog like appearance), is one of Australia’s most iconic extinct mammals. Thylacines are thought to have gone extinct in the wild by the 1930s, with the last surviving captive animal having died in 1936. This was due, to a mass-extermination of the thylacines across Tasmania. Sadly, despite their now iconic nature and more recent public interest, very few useful specimens exist in collections and a complete atlas of the skeleton of the Thylacine has never been published. This is where a recent PE paper by Natalie M. Warburton, Kenny J. Travouillon, and Aaron B. Camens comes into play.

A complete skeletal atlas

The recent paper by Dr Warburton and her team provides a record of the skeletal anatomy of the Thylacine. Having a reliable reference for future studies is incredibly important for the Thylacine as Dr Warburton explains:

“Having reliable and accessible reference material is really important in order to answer lots of palaeontological questions. From the basics of "what is this bone?” and “who did it belong to?”, to understanding the patterns in bone morphology that correspond to adaptations for different behaviours versus those that correspond to phylogenetic patterns.”

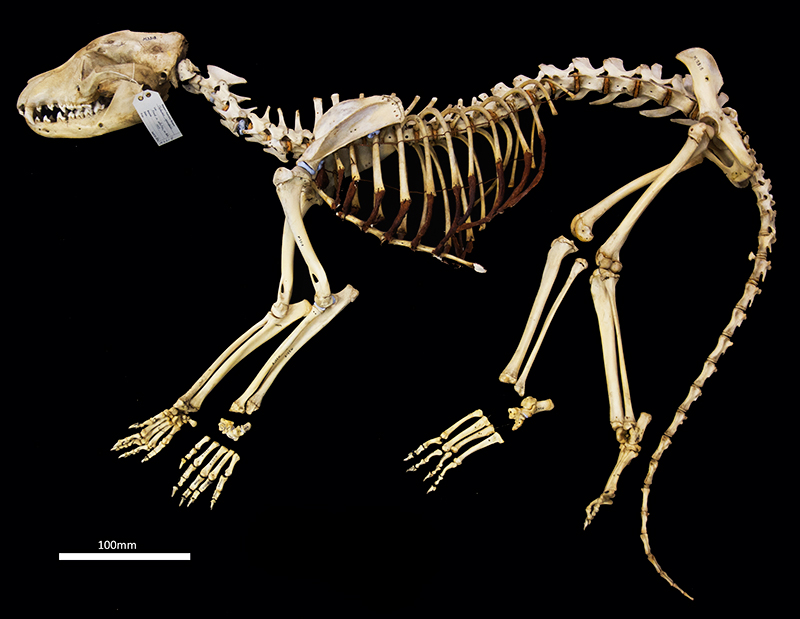

Thylacine skeleton, WAM M195 (M3318) (Figure 1 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Thylacine skeleton, WAM M195 (M3318) (Figure 1 of Warburton et al. 2019).

A complete atlas such as this is incredibly important for palaeontologist and biologist to be able to complete their research in cases where they cannot access the original specimens. “Ideally we would have access to lots of complete comparative specimens when we are working, but often times this is just not practical” Dr Warburton says, “Even when working with access to museum collections, there are often limited numbers of complete skeletons available, and this is particularly the case for relatively rare or extinct species.”

Is it a Thylacine?

Perhaps the greatest value is that this atlas will allow for easier identification of Thylacine specimens, particularly those often overlooked in the fossil record. Dr Warburton says:

“An atlas, such as the one we have put together for the Thylacine, provides a very valuable resource for those trying to make decisions about whether or not the bones they have found are likely to be from a Thylacine, and if not, how the bones compare in the morphology in such a way that might give clues to who the bones did belong to. Little bones, such as epipubic bones [part of the pelvic area], fabellae [a small boke in the leg] and chevron bones [part of the tail] are also something that are often overlooked, but can turn up in fossil deposits - often they might end up in the bag of unidentified bony bits that no one ever looks at; we have included illustrations of these as well.”

Any good comparative atlas should include photos of bones from multiple angles. “By providing photos of each bone from many different angles, it will help in the identification and comparative study of even fragmentary bones” Dr Warburton explains.

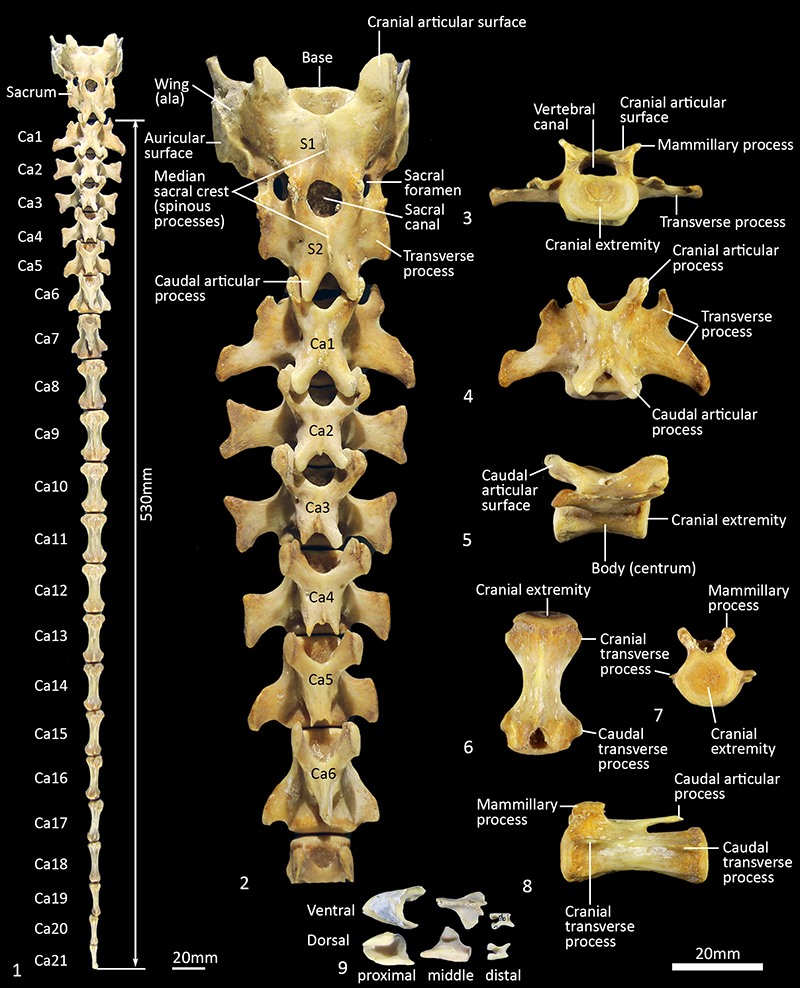

Sacral and caudal vertebrae SAMA M1960. 1, complete sacro-caudal series, dorsal view; 2, sacrum and proximal caudal series, dorsal view; 3, first caudal vertebra (Ca1) cranial view; 4, Ca1 dorsal view; 5, Ca1 lateral view; 6, eighth caudal vertebra (Ca8) ventral view; 7, Ca8 cranial view; 8, Ca8 lateral view; 9, examples of proximal, middle and distal chevron bones from ventral and dorsal views. Scale bar equals 20 mm (Figure 17 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Sacral and caudal vertebrae SAMA M1960. 1, complete sacro-caudal series, dorsal view; 2, sacrum and proximal caudal series, dorsal view; 3, first caudal vertebra (Ca1) cranial view; 4, Ca1 dorsal view; 5, Ca1 lateral view; 6, eighth caudal vertebra (Ca8) ventral view; 7, Ca8 cranial view; 8, Ca8 lateral view; 9, examples of proximal, middle and distal chevron bones from ventral and dorsal views. Scale bar equals 20 mm (Figure 17 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Not a tiger, not a dog, not just from Tasmania

Despite one common name being the Tasmania Tiger, the Thylacine is bears little resemblance to an actual tiger. However, the skeleton does share incredible physical resemblance with dogs or wolves.. Despite this, the thylacine is actually a marsupial (the group that includes kangaroos, possums, quolls and koalas)! We discussed this common misconception with Dr Warburton:

“Thylacines do look very much like dogs - this similarity is an exquisite example of convergence between a marsupial and the eutherian “dog” (family CANIDAE), and reflects evolution towards a similar ecological niche; that of a pursuit predator. However, as well as functional patterns, the skeleton and teeth also preserve many characteristics of taxonomic significance.”

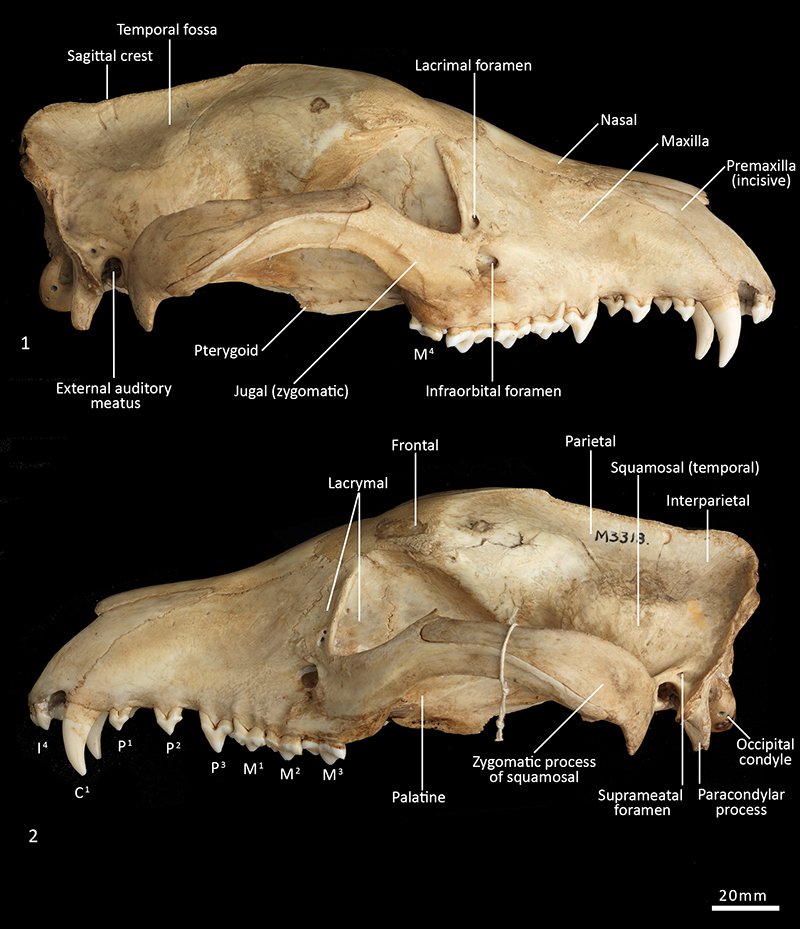

Skull of WAM M195 (M3318). 1, right lateral view; 2, left lateral view. Scale bar equals 20 mm (Figure 4 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Skull of WAM M195 (M3318). 1, right lateral view; 2, left lateral view. Scale bar equals 20 mm (Figure 4 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Dr Warburton explains that there are several differences between marsupials and eutherian mammal skulls including: nasal bones that expand, rather than converge towards the back of the nose; auditory bullae (a hollow bony structure on that encloses parts of the middle and inner ear) principally formed from the alisphenoid bone; the lachrymal duct (tear duct) positioned outside the orbit on the expanded lachrymal bone and more! “The post cranial skeleton (everything below the skull) also has lots of little features that reflect the fact that the Thylacine is a marsupial, not a dog - most obviously, the presence of epipubic bones [pelvic bone], but also the bones of the wrist and ankle, length of metacarpal and metatarsal bones, and the list goes on” say Dr Warburton.

For those interested in deep-diving into marsupial morphology, many of these features are clearly labelled in the new atlas of the Thylacine skeleton.

The name Tasmania Tiger or Wolf is also somewhat of a misnomer given that the Thylacine was not solely restricted to the state of Tasmania. Although by the time European settlers arrived Thylacines no longer occurred on the mainland, Dr Warburton points out that “Thylacines were represented in rock paintings and fossil deposits across the Australian mainland until between 3-4 thousand years ago.”

A treasure hunt for new information

Creating a new atlas of the skeleton of the Thylacine was not always easy. “In conducting this research, it also became a bit of a treasure hunt through the museum archives to actually workout where the specimens came from” Dr Warburton explains “Kenny [Travouillon] eventually tracked down letters that indicated that the specimen ID on at least one of the WAM skeletons was incorrect, and so we have clarified the origins of these specimens too.”

Dr Warburton was also surprised by some of the convergent similarities between eutherian mammals and Thylacines:

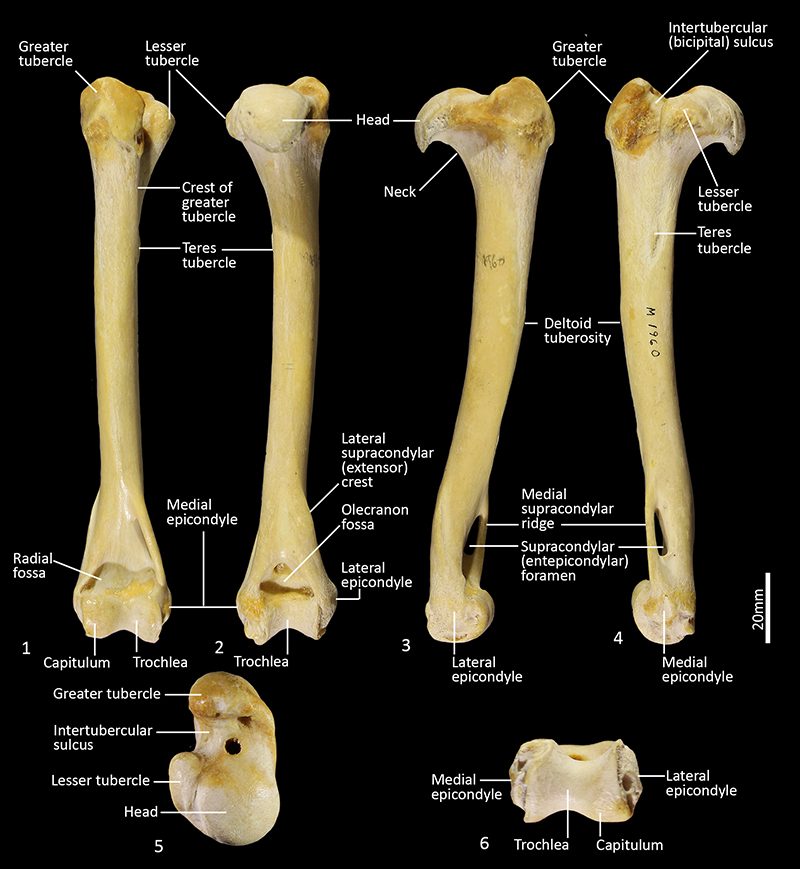

“Having not spent a lot of time looking at Thylacine bones before, I was struck by how strongly convergent many of the limb bone features are with cursorial [limbs adapted for running] eutherian mammals - Features like the really anteriorly projecting greater tubercle of the humerus, and much more digitigrade stance of the carpal and tarsal regions. Then there are the epipubics – in comparison to all other terrestrial marsupials they are tiny, and I think these suggest that Thylacines were moving their trunk and hindlimbs much more like cursorial placental mammals do than other marsupials.”

Right Humerus SAMA M1960. 1, cranial view; 2, caudal view; 3, lateral view; 4, medial view; 5, proximal view; 6, distal view. Scale bar equals 20 mm; NB 5 and 6 not to scale (Figure 22 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Right Humerus SAMA M1960. 1, cranial view; 2, caudal view; 3, lateral view; 4, medial view; 5, proximal view; 6, distal view. Scale bar equals 20 mm; NB 5 and 6 not to scale (Figure 22 of Warburton et al. 2019).

Dr Warburton hopes that “by providing detailed labels of many morphological features on the bones, it will help those that are not familiar with detailed bony anatomy to make sense of terms that are often described, but not necessarily well illustrated, in the (sometimes very old) literature that we often work with.” She hopes that this will be a really valuable reference work for all those (new and old) who study this iconic marsupial and, in general, the evolution of mammal bones.

To learn more about these fossils, check out the original PE article here.