Ancient Trophic Interactions

Ancient Trophic Interactions

Panama, the land bridge connecting the north and south American continents is known for its lush forests and tropical waters. This ideal central location between continents allowed two evolutionarily distinct wave populations of plants and animals to crash into each other creating a mixing pot of evolution. These novel interactions over the last ~10 million years has made Panama the lush green biodiversity hotspot we know today.

However, if we rewind to the Pliocene (5.3-2.58 million years ago) the land bridge was still developing. The region was sprinkled with islands separated by a warm shallow sea with a very thin isthmus, “ideal for marine megafauna, where whales, fishes, and abundant benthic invertebrates thrived” says Dirley Cortés.

Dirley Cortés is a researcher studying marine paleoecology of the Early Cretaceous, but also has fieldwork experience in the Panamanian region. It was these fieldwork connections that led to a recent discovery of whale remains which reveal interesting signs of shark predation.

Top: Professor Joaquin Atencio. Bottom: Local community members at the fossil discovery site.

Top: Professor Joaquin Atencio. Bottom: Local community members at the fossil discovery site.

In 2016 professor Joaquín Atencio, who is a former professor at the elementary school Colegio Punta Burica along with members of the local community; Félix Orocú, his son Joel Orocú, and Patricio Pimentel (these last two Atencio’s students), discovered the fossil remains. Soon after, professor Atencio contacted Dr. C. Jaramillo, staff scientist from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute in Panama which Cortés is also associated, a prospecting mission was planned, and the whale remains were collected together with a nearby shark tooth.

Community members and Dirley Cortés observing the whale remains.

Community members and Dirley Cortés observing the whale remains.

“The fact that only a forelimb was found may suggest that the carcass was consumed by scavengers, including sharks. Scavengers could have disarticulated the forelimb from the skeleton, which would have then sunk to the seafloor and eventually become buried by sediments” states Cortés.

And that is precisely what the evidence shows.

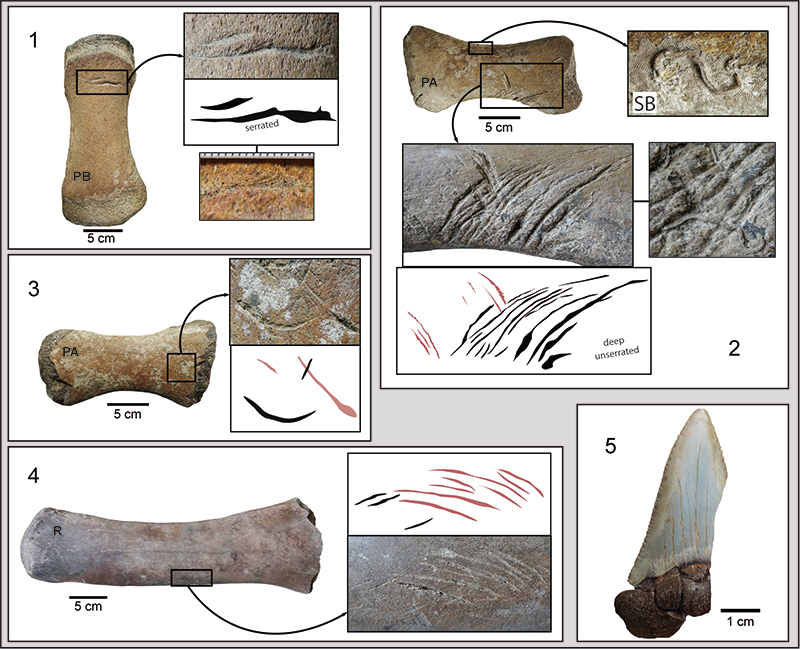

“Upon initial investigation of the bones, we noticed shark bite evidence over the phalanges and radius of the whale. After closer examination, we realized that there are two different kinds of shark bite marks on the bones; one serrated and the other very deep serrated” says Cortés.

Balaenopterid and shark remains from the late Pliocene of Panama.

Balaenopterid and shark remains from the late Pliocene of Panama.

The media has made sharks out to be bloodthirsty predators, actively hunting their prey, but would they also search out a free meal from a dead carcass?

“Although scavenging behavior in sharks is not well known, several observations of scavenging in sharks reported in recent literature have been hugely important to better our understanding between trophic interactions of sharks and whales” says Cortés.

Occasionally, other shark predation evidence can be found in the fossil record. There are even evidence sharks feasted on dinosaur carcasses from the Late Cretaceous. Based off the bite marks on the whale forelimb, the researchers have found the likely culprit.

“Carcharodon carcharias, the massive shark also known as the great white shark, likely caused the serrated bite marks. The unserrated mark is from continual gnawing of the same species, but more than one individual was likely snacking on the carcass” states Cortés.

This further supports the scavenging hypothesis, since different shark individuals are much more likely to swarm the same dead, smelly carcass instead of hunting the same prey.

Although the scarce remains portray little about the whale’s ecology, researchers were able to determine what kind of whale they belonged to.

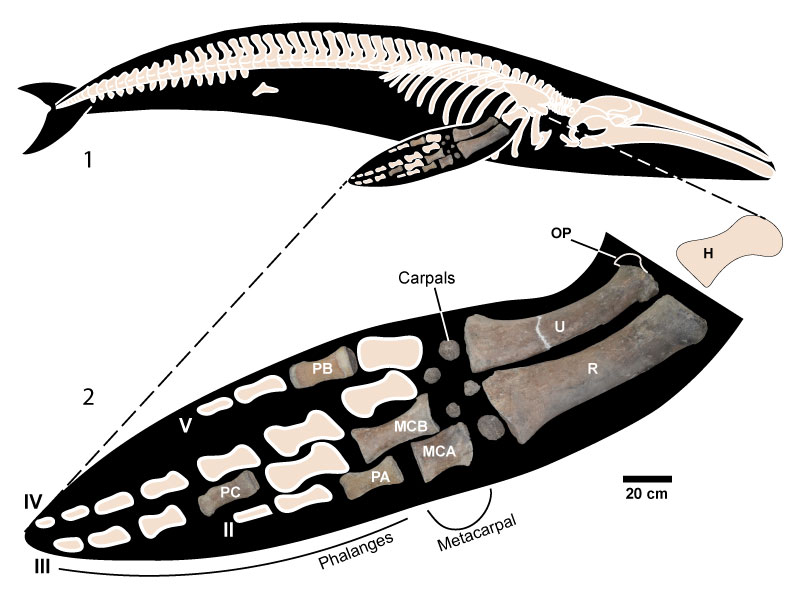

Right lateral view of the skeleton of a generalize mysticete whale with the remains highlighted.

Right lateral view of the skeleton of a generalize mysticete whale with the remains highlighted.

“Among marine mammals, cetaceans are the best example of complete adaptation to life in water. Unlike toothed cetaceans (Odontoceti) which are mostly active predators, baleen whales (Mysticeti) which these remains likely belonged, lack teeth and use their baleens for filtering massive amounts of water while looking for food. These animals evolved to feed on large amounts of plankton or fishes that live in modern oceans. Balaenopterids are the most common group of modern whales, commonly referred as rorquals, including the largest animal to ever live on the planet, the blue whale” shares Cortés.

“Whales are among the most common fossils in large fossiliferous Cenozoic marine deposits. However fossil localities with whale bones in Central America are remarkably scarce” shares Cortés. “This time period is essential for understanding the final establishment of modern faunas since the last time mega-predators furrowed the seas in the Miocene.”

Not only does this research have implications for the ecology of marine faunas, but also acts as a snapshot of past environments.

“Fossil marine mammals, like the one described in this study, are useful for understanding the dynamics of marine fauna in one of the most critical periods of Earth history, the Plio-Pleistocene transition” says Cortés.

Not only was this a time of changing climate, sea-level oscillations, and significant extinction-origination events, but also by directly preceding modern times, resulted into the world we know today.

To read more about this discovery, you can access the original article here!