In a July 2020 study in Palaeontologia Electronica, paleontologist Adiël A. Klompmaker and colleagues identified several Mesozoic crab specimens from sponge and coral-associated limestones in Europe. The researchers described six new taxa, reassigned several others, and documented some spectacular finds.

An Explosion of Diversity

While dinosaurs roamed the Earth, crabs flourished in the sea. Originating in the Early Jurassic, crabs became very diverse for the first time during the Late Jurassic, filling the habitat offered by expanding coral reef ecosystems. They continue to be the most diverse decapod group today, accounting for nearly half the species in this order of ten-legged crustaceans!

With so much diversity, there is a lot to learn and discover using the fossils preserved in reef-associated limestones. The researchers examined a variety of Late Jurassic and mid-Cretaceous specimens from Central Europe, back when tropical oceans covered much of the continent.

A Crab Conundrum

Paleontologists face an interesting challenge when identifying fossils: convergent evolution.

“Convergent evolution has occurred when two taxa that are not closely related look very similar, often due to having a similar lifestyle,” said Dr. Klompmaker. “Think for example of a wolf and a Tasmanian wolf. They look alike, but one, the wolf, is a placental mammal, whereas the Tasmanian wolf is a marsupial mammal. They are only very distantly related.”

While biologists can use molecules to figure out if species are closely related, paleontologists must rely solely on the clues left behind by fossils— the shape and size of the animal’s physical features.

“As the form and size of organisms is influenced by their ancestors, but also other factors such as their ecology and environment they live in, morphology can sometimes be tricky to use to correctly classify organisms,” Dr. Klompmaker said.

This raises the question as to how scientists tell if two species are related or if they simply experienced convergent evolution.

“The key is to find features of organisms that are least influenced by environmental and ecological factors,” said Dr. Klompmaker. “For crabs, the form of the legs says a lot about their lifestyle (swimming, digging, etc.), so legs can be difficult to use to study the relatedness between crabs because unrelated crabs can have a similar lifestyle.”

Solving Mysteries

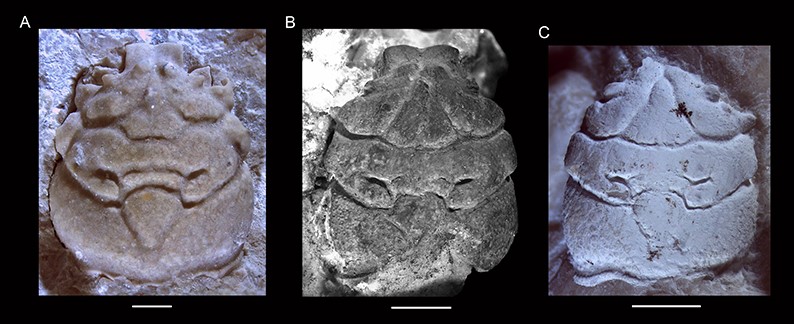

A comparison of Rathbunopon (A) and Europrosopon (B&C) fossils. [Figure 10A-C in original article]One Cretaceous crab from the study, Rathbunopon, has been particularly tricky, with scientists debating its classification on the basis of convergent evolution. Rathbunopon strongly resembles another crab now called Europrosopon, but some researchers have placed them in separate superfamilies because of their dissimilar eye sockets, implying the two are simply unrelated lookalikes.

A comparison of Rathbunopon (A) and Europrosopon (B&C) fossils. [Figure 10A-C in original article]One Cretaceous crab from the study, Rathbunopon, has been particularly tricky, with scientists debating its classification on the basis of convergent evolution. Rathbunopon strongly resembles another crab now called Europrosopon, but some researchers have placed them in separate superfamilies because of their dissimilar eye sockets, implying the two are simply unrelated lookalikes.

“The eye sockets do differ somewhat indeed, but we also know that the form of eye sockets can vary quite a bit, even within a single genus of crab. Moreover, all other features of Rathbunopon and Europrosopon are identical or nearly so.” Dr. Klompmaker said.

As a result, the researchers reassigned Rathbunopon to the same family as Europrosopon, deciding that convergent evolution was, in this case, unlikely.

Another Cretaceous crab from the study, Navarradromites, tells a different story.

“Navarradromites has some features in common with members of the family Homolodromiidae such as spines near the eyes of this crab,” Dr. Klompmaker explained, “but there are far more other characters that align them with members of the family Goniodromitidae, particularly the genus Eodromites.”

In this case, convergent evolution more easily explains the eye spines, so the researchers placed the crab in Goniodromitidae.

Carefully weighing similarities and differences in fossils allows paleontologists to continually improve our understanding of how ancient animals relate to one another.

Fantastic Firsts

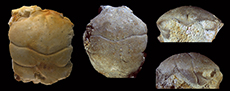

Large swelling from an epicaridean isopod parasite. [Figure 9C in original article]This study identified six new species of crab, but that’s not all that’s new! One specimen of Abyssophthalmus spinosus is the largest complete Jurassic crab ever documented at 39.1 mm long. However, this is still much smaller than its Cretaceous counterparts.

Large swelling from an epicaridean isopod parasite. [Figure 9C in original article]This study identified six new species of crab, but that’s not all that’s new! One specimen of Abyssophthalmus spinosus is the largest complete Jurassic crab ever documented at 39.1 mm long. However, this is still much smaller than its Cretaceous counterparts.

Another specimen from the Jurassic has a curious swelling in the right gill region of its carapace (shell), likely to have been caused by a parasitic crustacean called an epicaridean isopod. These isopods are still found in crabs today, and given this evidence, the relationship between epicarideans and crabs emerged soon after crabs first appeared. This is one of the largest swellings relative to crab size in the entire fossil record!

To read more about this study, you can find the original article here.

Kerste Milik

Kerste Milik