Without a skeleton or a hard shell, an animal’s chances of becoming a fossil are very slim. But under the right conditions, even soft-bodied animals like insects and spiders can be fossilized. A recent paper in Palaeontologia Electronica describes several Eocene spider fossils that were remarkably well preserved, including two new species.

Without a skeleton or a hard shell, an animal’s chances of becoming a fossil are very slim. But under the right conditions, even soft-bodied animals like insects and spiders can be fossilized. A recent paper in Palaeontologia Electronica describes several Eocene spider fossils that were remarkably well preserved, including two new species.

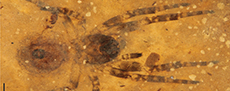

Greenwaltarachne pamelae sp. nov. (left) and Consteniusi leonae sp. nov. (right) [Figures 4A & 3A in original paper]

Greenwaltarachne pamelae sp. nov. (left) and Consteniusi leonae sp. nov. (right) [Figures 4A & 3A in original paper]

Identified in 2020 by researchers Matthew Downen and Paul Selden, the spiders were originally discovered in the Kishenehn Formation of Montana, USA. This 46-million-year-old lake deposit is a hotspot for fossils, including soft-bodied animals. “Insects and spiders are preserved in amazing detail,” said Dr. Downen. “So much so, that [researchers] even recovered a fossil of a blood-engorged mosquito.” According to Downen, sticky microbial mats on the surface and bottom of the ancient lake likely provided ideal conditions for preserving these animals.

When you think of a fossilized insect or spider, you may imagine animals encased in amber, similarly to the famous depiction in Jurassic Park. While spiders in amber are preserved in 3D, these Kishenehn spiders are 2D impressions in rock, which presents unique challenges for identification. “Diagnostic characteristics like eyes, reproductive structures, and spinnerets are commonly used in spider taxonomy, but these features are often not clearly visible or may not be visible at all in spiders preserved in rock!” said Dr. Downen. The fossils were also obscured by a film of silica, requiring special laboratory preparation to make the spiders appear clearly.

Despite these challenges, Downen and Selden successfully identified spiders from the Kishenehn Formation for the first time. These are the oldest spider fossils found in Montana, and include two new species, Consteniusi leonae sp. nov. and Greenwaltarachne pamelae sp. nov..

“My favorite spider from this collection is Consteniusi leonae, nicknamed Leona's spider,” said Dr. Downen. “I saw a picture of it several years ago and noticed it was beautifully preserved. Later, Dale Greenwalt from the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History reached out to me about the Kishenehn spiders and tracked down Leona's spider.”

This unique collection of spiders adds to our understanding of the diversity of ancient life in North America, helping us paint a more accurate picture of the past.

To read more about this study, you can find the original article here.