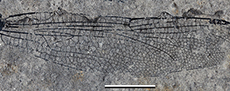

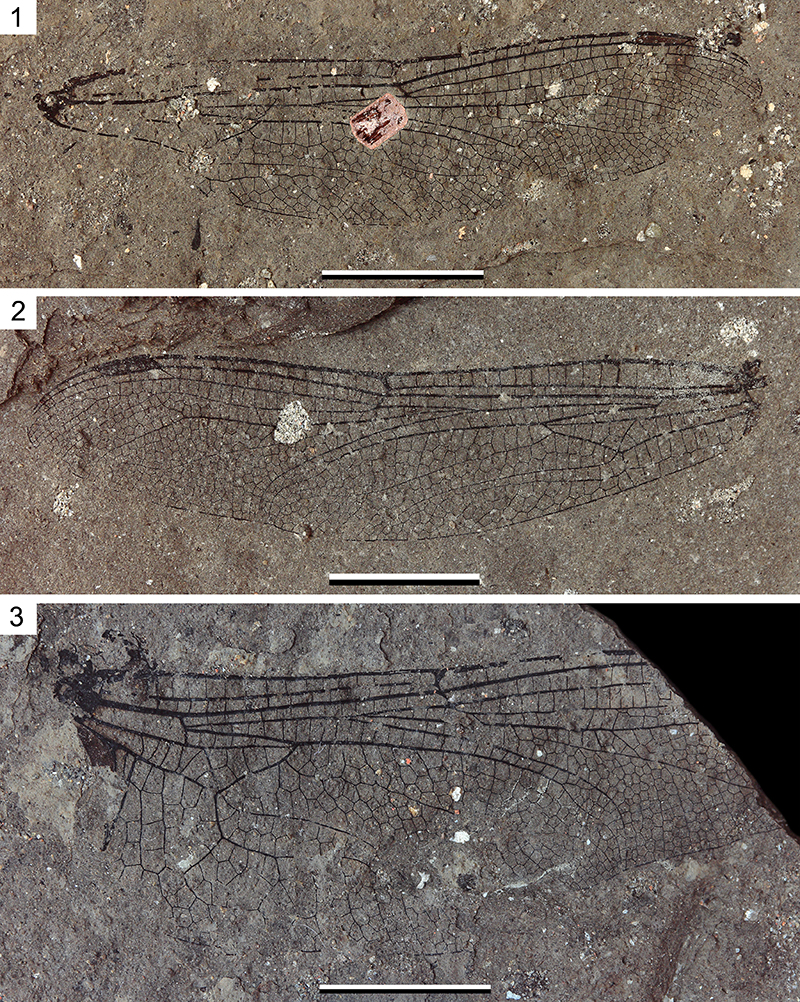

Small creatures can often provide big insights into past worlds. A recent paper published in Palaeontologia Electronica describes ten fossil Odonata (dragonflies and their relatives) wings from the Oligocene palaeolake Enspel. These wings, along with several well-preserved naiads (larval dragonflies), help paint a picture of a vibrant, Figure 1. Nel et al. 2021 used the venation in wings such as these to identify different subgroups within Odonata. and buzzing, lost world in what is today southwestern Germany.

Figure 1. Nel et al. 2021 used the venation in wings such as these to identify different subgroups within Odonata. and buzzing, lost world in what is today southwestern Germany.

The palaeolake Enspel, according to André Nel, one of the researchers on the study, was “a freshwater lake with water of rather good quality, oligotrophic, high oxygen level probably, with a rich aquatic fauna, under a climate warmer than today, thus with a rich entomofauna.”

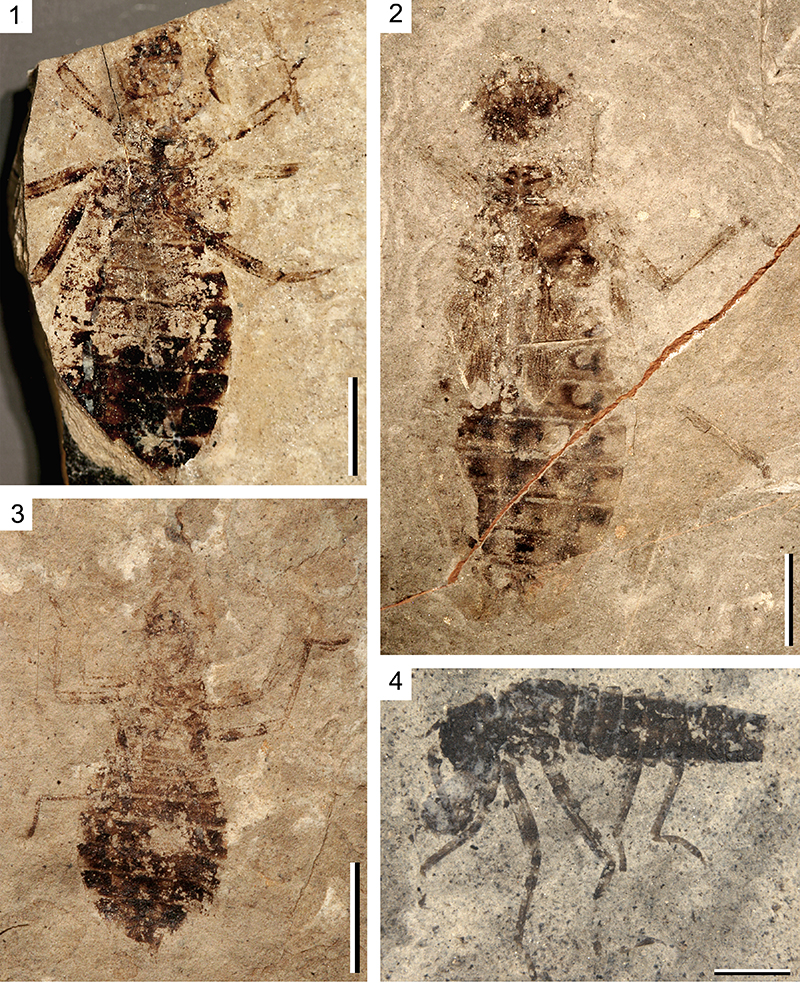

Naiads are the carnivorous and aquatic larvae of dragonflies. The presence of naiads at the lake suggests that Enspel was a rich, productive body of water. For larvae to be present in the lake would indicate that dragonflies were not merely visitors, but that they hatched, buzzed, hunted, and died here. Multiple generations of dragonflies living and hunting at the palaeolake very likely means that Enspel Lake had some degree of permanence on the Oligocene German landscape. A population of carnivorous and predatory naiads also suggests the presence of a community of prey species for these voracious little larvae. Enspel was not an ephemeral pond, but a well-established and diverse community.

While larval insects, the naiads, are represented by full body specimens, the adult dragonflies are almost exclusively present at Enspel in the form of fossilized wings. “Wings are structures that the predators do not eat… thus wings have more 'chance' to be fossilized than the bodies. They are rejected by predators and become easily buried,” André Nel explains. One can imagine one of these Oligocene dragonflies being snatched from the sky by some plucky bird or grabbed by a terrestrial critter. As the dragonfly’s happy adversary munches on its arthropod treat, it bites off a pair of wings which gently helicopter down to the lake’s surface. After sinking to the lake bottom the wings are buried by sediment and eventually fossilize. Millions of years later, a team of researchers uncover the wings and gain insight into a local lake community in a Germany of long ago. The fossil wings themselves are quite vividly preserved, and the story they tell – of the life, death, and preservation of a single insect – allow us to catch a glimpse into a past long forgotten. Figure 2. The presence of naiads at Enspel suggests a body of water that was rich and permanent enough for multiple generations to grow and develop.

Figure 2. The presence of naiads at Enspel suggests a body of water that was rich and permanent enough for multiple generations to grow and develop.

One might think that the prevalence of wing fossils over body fossils at the Enspel locality would make identification of different dragonfly species difficult – but never fear. By happy coincidence, the venation of dragonfly wings is quite diagnostic (useful in identification) of different lineages in Odonata, the biological grouping including dragonflies and damselflies. In the current study (Nel et al. 2021), the team of researchers identify seven different species of Odonata based solely on these wings. Among these include wing fossils of

representatives of Aeshnidae, Gomphidae, and Sieblosiidae – all subgroups within Odonata. Represented by naiads are Libellulidae and Lestidae. In addition, based

on these wings, the study names three whole new species - Epiaeschna wisseri sp. nov. (Aeshnidae), Ictinogomphus engelorum sp. nov. (Gomphidae), and Oligolestes stoeffelensis sp. nov. (Sieblosiidae). Modern relatives of these families include “hawking” (dragonflies that hunt on the wing) and “perching” (ambush predators) ecologies. Like the presence of multiple generations, this diverse set of insect ecologies points to a palaeolake community that was well-developed and thriving.

The fact that the study can glean the above information (the development of the lake community and the taxonomy of that community’s denizens) all from the preserved wings of dragonflies and their larvae is truly remarkable. It is a testament to ingenuity of modern biology and the importance of small creatures in a very big world.

To read more about this study, you can find the original article here.