A giant, crocodile-like predator lurked in North American wetlands during the Late Triassic, dominating the food chain. But even this mighty creature, Smilosuchus gregorii, could not escape the threat of disease.

“The natural world has always been harsh and unforgiving,” said Dr. Andrew Heckert, a paleontologist at Appalachian State University.

USNM V 18313, Smilosuchus gregorii, Smithsonian Institution. Used with permission. (Newsdesk Article)

USNM V 18313, Smilosuchus gregorii, Smithsonian Institution. Used with permission. (Newsdesk Article)

Dr. Heckert and his fellow researchers recently published an in-depth study of a unique phytosaur specimen with extensive evidence of disease on its skeleton. Visitors to the National Museum of Natural History may be familiar with the specimen, recently added to their exhibit hall in 2019.

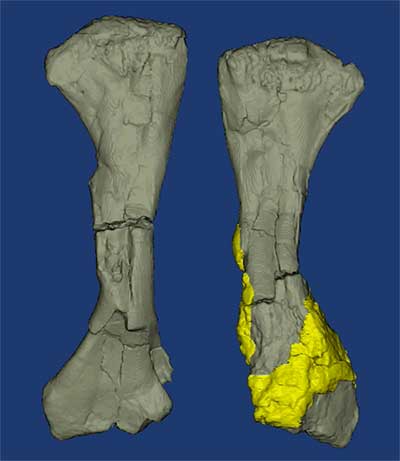

“A glance at any of the major bones shows that something was seriously wrong,” said Dr. Heckert. With extensive pathological bone growth affecting eight limb bones, it is clear that the animal was suffering from this condition for a long time before dying.

Diagnosing a 200-million-year-old disease can be challenging, but there are relatively few infectious diseases that leave definitive evidence on the skeleton. Therefore, the researchers determined the size, shape, and location of the lesions were best attributed to osteomyelitis, an infectious inflammation of the bone.

Rendered CT-scan of humeri of USNM 18313. Pathological bone is highlighted in yellow. Click here to download Quicktime movie.

Rendered CT-scan of humeri of USNM 18313. Pathological bone is highlighted in yellow. Click here to download Quicktime movie.

“People have spent a lot more time looking at dinosaurs in general, and pathologies in dinosaurs specifically, than in animals like phytosaurs, yet here is a phytosaur with two pathological femora – something we have never seen in a dinosaur,” said Dr. Heckert.

This Smilosuchus likely survived for several months, or even years, with its legs compromised. This suggests that phytosaurs may have been semi-aquatic, because wading or swimming requires less reliance on leg support to survive.

“Few things remind you that a fossil was once a living organism than seeing how it was affected by a disease or injury—there’s something there that tells the story of its life,” said Dr. Heckert.

While we may never know this Smilosuchus’ full life story, this research gives us a glimpse of its troubled yet persistent life.

This study was years in the making, with Dr. Heckert initiating the research in 2007 as a collaboration between two paleontologists and a wildlife pathologist. During the COVID-19 pandemic, as much field research was put on hold, the team of scientists were finally able to publish their data in Palaeontologia Electronica, complete with animated CT-scans of the specimen. You can find the full publication here.