Sapporo, Japan, is a fast-moving, modern city of nearly two million people. International readers may twig to it as the birthplace of miso ramen and the Sapporo beer brand, but locals also think of northerly Sapporo as a hub for winter sports and the home of a multi-pennant-winning baseball team. Most people aren’t aware of Sapporo’s fossil history, but the chance discovery of a 9-million-year-old whale missing link may change all that.

Sapporo, Japan, is a fast-moving, modern city of nearly two million people. International readers may twig to it as the birthplace of miso ramen and the Sapporo beer brand, but locals also think of northerly Sapporo as a hub for winter sports and the home of a multi-pennant-winning baseball team. Most people aren’t aware of Sapporo’s fossil history, but the chance discovery of a 9-million-year-old whale missing link may change all that.

(A) Photo taken at beginning of excavation in 2008 showing whale backbone. (B) Whale excavation in 2009.Sapporo resident Dr. Kazuhisa Mori was certainly not thinking about fossil whales when he stopped on the banks of the Toyohira River in October 2008. Mori was on his way to a rugby pitch in a mountainous region southwest of Sapporo, well away from the prime whale habitat off the coast, when he stopped to photograph the beautiful warm tones of the fall foliage. That’s when he noticed the bones in the riverbed. Mori, a medical doctor, could not mistake the shape of a vertebra and several footlong ribs.

(A) Photo taken at beginning of excavation in 2008 showing whale backbone. (B) Whale excavation in 2009.Sapporo resident Dr. Kazuhisa Mori was certainly not thinking about fossil whales when he stopped on the banks of the Toyohira River in October 2008. Mori was on his way to a rugby pitch in a mountainous region southwest of Sapporo, well away from the prime whale habitat off the coast, when he stopped to photograph the beautiful warm tones of the fall foliage. That’s when he noticed the bones in the riverbed. Mori, a medical doctor, could not mistake the shape of a vertebra and several footlong ribs.

Mori’s discovery led to four years of diligent labor by a team from the Sapporo Museum Activity Center to preserve the fossil bones. This was well-rewarded as their work unearthed a mostly complete skeleton, including the back of the skull, that they recognized as a whale. Scrutiny soon revealed the skeleton belonged to a new type of whale, which they called Megabalaena sapporoensis. Analysis of the sediments around the specimen indicated it was approximately 9 million years old, dating back to the Late Miocene. Dr. Yoshi Tanaka, the lead author of the study describing Megabalaena, states that the area was “a deep ocean with small shallow oceans around some volcanic island[s]” at this time. Our knowledge of this environment, says Tanaka, is “limited” – the only other fossil animal known from this part of Sapporo’s prehistory is a giant sea cow called Hydrodamalis, so the whale discovery alone is significant for Japanese palaeontology. But even greater importance to scientists globally is what the discovery can tell us about whale evolution.

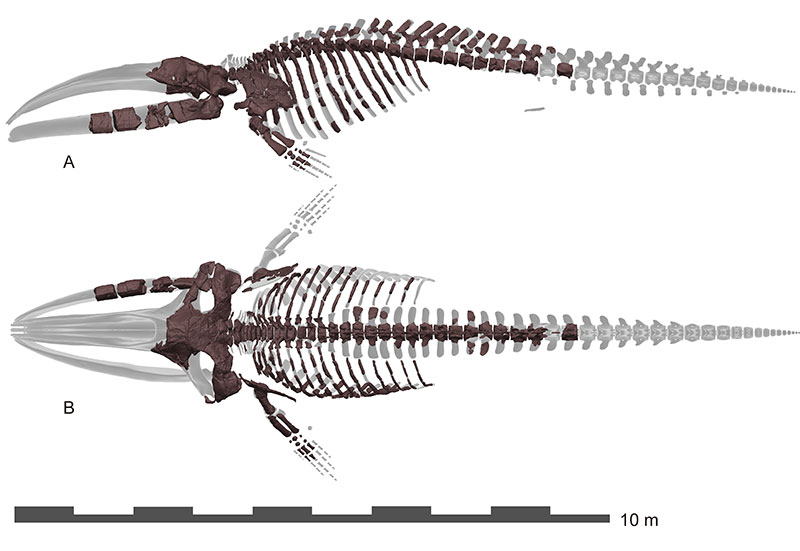

Tanaka and his colleagues analyzed the whale specimen carefully to determine its closest relatives and realized they had found a ‘missing link’ in balaenid whale evolution. Modern balaenids, represented by bowhead and right whales, are large beasts around 17 m long. But their most recent ancestors, from the Pliocene (5.33 to 2.58 million years ago), are small, and so are their distant ancestors – the twenty-million-year-old Morenocetus purvus is only 4.2 meters long. This leaves many open questions about how balaenids evolved to become such large animals in modern oceans. Making matters worse, there is a big gap in the balaenid fossil record – from 15.2 to 6.1 million years ago – leaving a lot of fossil data unaccounted for that could potentially solve this evolutionary problem. So, at 9 million years old, Megabalaena is perfectly placed to fill in a major gap in balaenid evolution. Preserved parts of Megabalaena viewed from the left (A) and above (B).

Preserved parts of Megabalaena viewed from the left (A) and above (B).

A first level of insight was provided when Tanaka and colleagues examined the anatomy of the specimen. Tanaka says they found “it had a slender body including slender fore flippers.” This led them to conclude that “Megabalaena sapporoensis had something different [of a] lifestyle to that of modern right whales”, a possibility which they want to investigate more in the future. But the most important anatomical detail of Megabalaena is its size: it was big, 12.7-15 meters long! This shows that large size is not just a feature of modern balaenids – instead, some of their early ancestors were pretty big too.

Further discussion of balaenid size evolution will likely require the discovery of new specimens, but Tanaka hopes that “older and larger monsters might be presented more clearly in the future.”

Tanaka also expressed his high hopes for future discoveries in Sapporo: “Regarding fossils, Sapporo is not … a rich fossil and famous area. We know [of] only a few fossil vertebrates. One is an individual of a giant sea cow (Hydrodamalis sp., reported in 2009). The second one is Megabalaena sapporoensis, which we publish now. So, Megabalaena sapporoensis and Hydrodamalis sp. are revealing possibilities for more findings in the future.” At the moment, Tanaka and his colleagues are working hard to share the discovery with the public and build local awareness of palaeontology, which should lead to further fossil discoveries. Mori, the specimen’s original discoverer, wrote an essay describing his discovery and shared it with his medical colleagues. The fossil of Megabalaena itself is now on display to the public in a special exhibition called “The World's Best Right Whale Fossil” at the Sapporo Museum Activity Center, which also held a press conference to show their find off to national media. In time, this discovery may prove to be a tremendous boon for science and education in Hokkaido, a vision Tanaka expressed. “Sapporo City has been searching for possibilities [to] establish a museum,” he said, “So, such [a] well-preserved right whale fossil [like] Megabalaena sapporoensis must increase [the] possibility for that.”

To discover more about this research, you can read the full publication here.

Reconstruction of Megabalaena by Tatsuya Shinmura.

Reconstruction of Megabalaena by Tatsuya Shinmura.