The pterosaurs, the remarkable flying reptiles of the Mesozoic, have been known to science for nearly 250 years. These animals flew on membraneous wings that extended from their greatly elongated fourth finger down to their ankles. They ranged in size as adults from just under a meter in wingspan to more than 10 meters, and have been found on every continent, but to date are known from only around 250 species. The first descriptions of their fossils predate those of the dinosaurs by decades, and those first pterosaurs came from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen beds of southern Germany. Some of the most iconic and best-known species come from this area, include the namesake of pterosaurs – Pterodactylus, and the extremely common and well-studied Rhamphorhynchus.

The pterosaurs, the remarkable flying reptiles of the Mesozoic, have been known to science for nearly 250 years. These animals flew on membraneous wings that extended from their greatly elongated fourth finger down to their ankles. They ranged in size as adults from just under a meter in wingspan to more than 10 meters, and have been found on every continent, but to date are known from only around 250 species. The first descriptions of their fossils predate those of the dinosaurs by decades, and those first pterosaurs came from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen beds of southern Germany. Some of the most iconic and best-known species come from this area, include the namesake of pterosaurs – Pterodactylus, and the extremely common and well-studied Rhamphorhynchus.

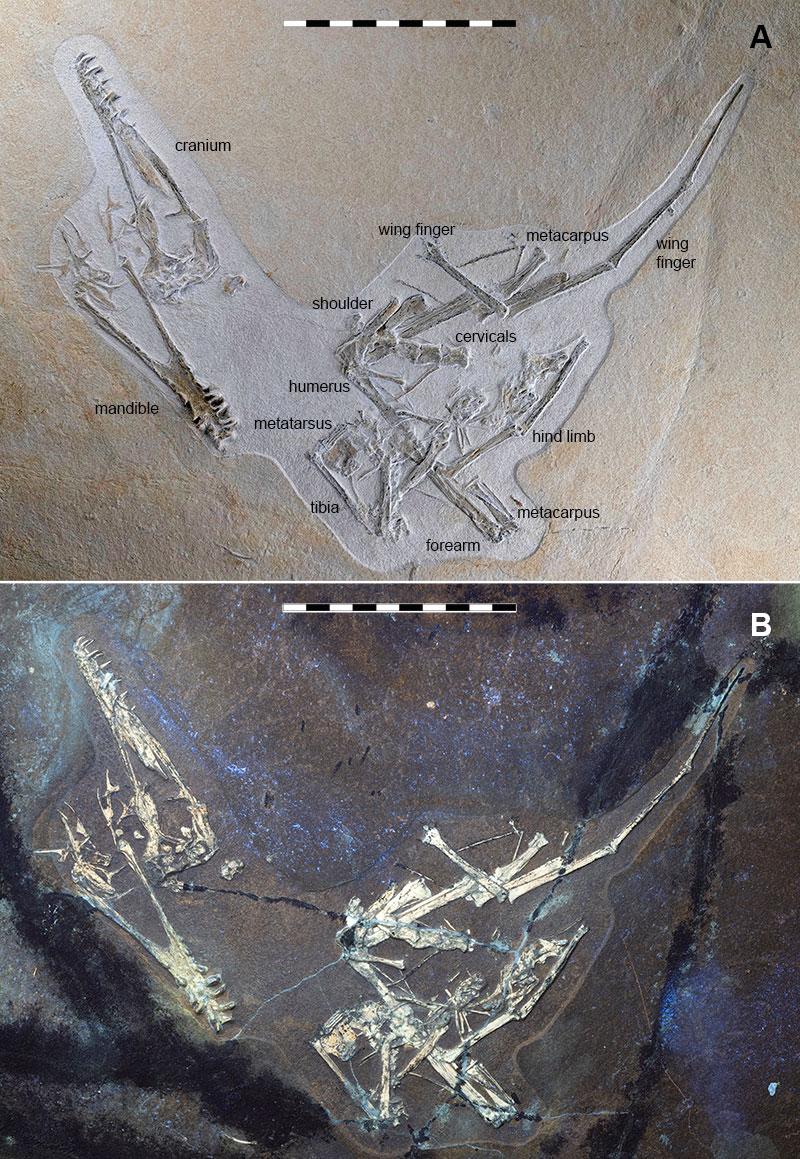

For two centuries, pterosaurs were essentially split between these two and their relatives – the earlier group of pterosaurs were called the ‘rhamphorhynchoids’ and were characterised by having relatively short heads on short necks, long tails, a short metacarpal in the wrist and a long fifth toe on the foot with the later ‘pterodactyloids’ having the alternate condition – a large head on a long neck, short tail, long metacarpal and short fifth toe. All pterosaurs fitted fairly neatly into one category or the other but this raised the obvious question of when and how did one group evolve to produce the other? Holotype specimen (LF1370) of Makrodactylus oligodontus photographed under A) daylight and B) UV light. Scale bar equals 100 mm with 10 mm divisions.

Holotype specimen (LF1370) of Makrodactylus oligodontus photographed under A) daylight and B) UV light. Scale bar equals 100 mm with 10 mm divisions.

That answer appeared to have been solved in 2010 with the publication of Darwinopterus from the Middle Jurassic of China that had the large head and neck of pterodactyloids, with the rest of the body resembling that of the earlier pterosaurs. Since then, a couple of dozen specimens have been found or recognised that fit into this gap between the two, and these animals that go by the name of ‘early monofenestratan’ pterosaurs have begun to show us how the transition from one to the other took place. There are though, still some gaps and questions about this shift and a new fossil find from the Solnhofen region helps to fill that in.

My team and I have dubbed this new find Makrodactylus oligodontus which roughly means ‘long finger with few teeth’ as it is characterised (surprise, surprise) by a number a of features that include the proportionally long wing finger and a very low number of sharp and long teeth. It’s known from a nearly complete, though somewhat disarticulated, specimen, with almost all the major elements of the skeleton being present. The fossil was found in the Mörnsheim Formation which is from the Late Jurassic of southern Germany, but slightly younger (i.e. more recent) than most of the traditional Solnhofen beds that have produced so many pterosaurs.

To date, not many fossils have been dug up in the Mörnsheim compared to the Solnhofen, but what has turned up so far is generally different to the earlier species. This has included a large early pterodactyloid (Petrodactyle – also described in the pages of PE) and another early monofenestratan, Skiphosoura which helped resolve some of the changes from Darwinopterus to the pterodacyloids, in particular having a much shorter tail than earlier forms.

Makrodactylus is much smaller than Skiphosoura, and indeed is smaller than any of the adult early monofenestratans that we know of. It is an adult animal, or at least is likely close to being full grown, and so is apparently quite unusual in being this small (well under 1 m in wingspan). It is though, a similar size to a number of both earlier and later pterosaurs, so it’s not exceptionally tiny.

The new find does also point to a few changes going on that may help to further explain the transition from these early monofenestratans into the pterodactyloids. The first of these is in the tail. As noted, Skiphosoura had a much shorter tail than the earlier pterosaurs (though still longer than that seen in the pterodactyloids), and it also had a series of very long and thin rods that bound the bones of the tail together to make it stiff, another feature from the earlier ones absent in later forms. The tail of Makrodactylus is not well preserved with only a few bones being present. But the ones that are there are rather short and simple and appear to be from the middle of the tail and lack the binding rods, so imply that this animal has a short tail and perhaps this was even closer to the condition seen in the pterodactyloids.

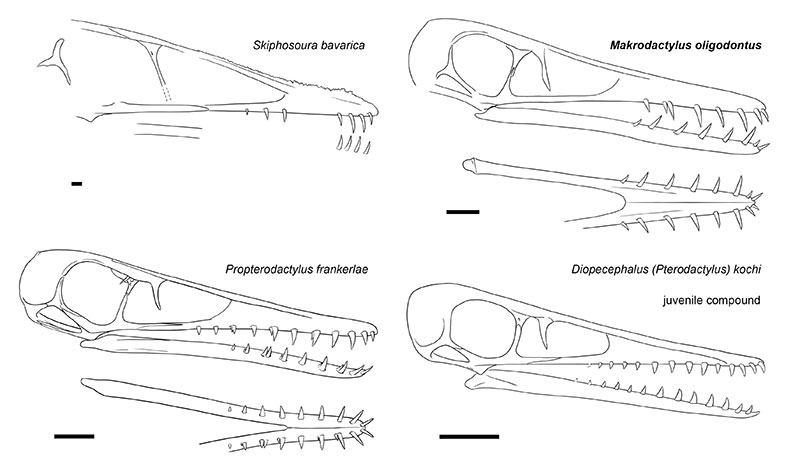

Comparison of reconstructed skulls of early monofenestran and pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Scale bars all equal 10 mm.Of more interest is the lengths of the four bones that make up the wing finger. Another feature of early pterosaurs is that the second and third bones are the longest, with a rather smaller first and last ones, but in the pterodactyloids, the first finger bone is the longest, and then the second, third and fourth in order. At some point this has to have transitioned from one condition to the other, and Makrodactylus may show this taking place. The lengths of its bones in the finger are almost all the same length (the end of the fourth is missing but our estimate has it as being close in length to the others, but the shortest overall). If at some point the second and third need to proportionally shift to be shorter than the first, which needs to be relatively longer, then a condition where the first, second and third are all around the same length could be a pathway to this.

Comparison of reconstructed skulls of early monofenestran and pterodactyloid pterosaurs. Scale bars all equal 10 mm.Of more interest is the lengths of the four bones that make up the wing finger. Another feature of early pterosaurs is that the second and third bones are the longest, with a rather smaller first and last ones, but in the pterodactyloids, the first finger bone is the longest, and then the second, third and fourth in order. At some point this has to have transitioned from one condition to the other, and Makrodactylus may show this taking place. The lengths of its bones in the finger are almost all the same length (the end of the fourth is missing but our estimate has it as being close in length to the others, but the shortest overall). If at some point the second and third need to proportionally shift to be shorter than the first, which needs to be relatively longer, then a condition where the first, second and third are all around the same length could be a pathway to this.

So, overall this nice little fossil does reveal some details about what was likely happening as the first pterodactyloids got going. This may seem slightly odd as you might have spotted that this animal was contemporaneous with at least some pterodactyloids and came after others. It would, therefore, be a late survivor of an earlier lineage that retained this intermediate condition. Such a thing is very common in evolution, new lineages do arise but don’t immediately replace their ancestors (or we wouldn’t have apes and all kinds of other primates around now), so this is not the contradiction it might first appear.

With a number of new species having been found in recent years, and more likely on the way, this is a boom time for the Solnhofen region. It has been an important source of pterosaur fossils for over two centuries and the fact that it continues to present new and important fossils bodes well for the future of our understanding of these incredible animals.

To discover more about this research, you can read the full publication here.

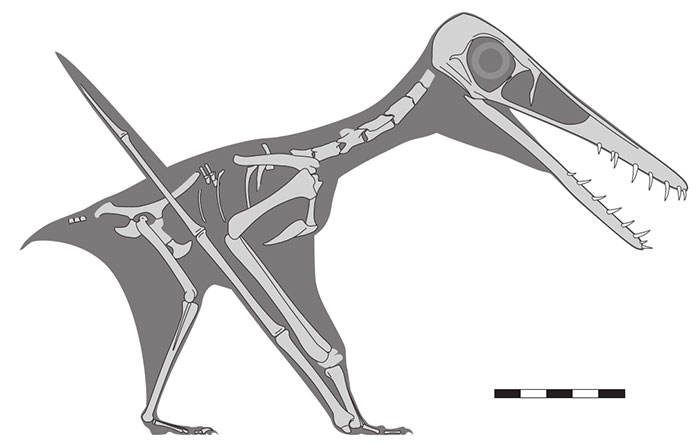

Restored skeleton of Makrodactylus oligodontus viewed from the right side in a standing posture showing the preserved elements (pale grey) and inferred body and soft tissues (dark grey). Scale bar in 50 mm with 10 mm divisions.

Restored skeleton of Makrodactylus oligodontus viewed from the right side in a standing posture showing the preserved elements (pale grey) and inferred body and soft tissues (dark grey). Scale bar in 50 mm with 10 mm divisions.