Mesotheriines of BOLIVIA

It is only within the past 35 years that mesotheriines have been known from the Bolivian Altiplano (Marshall and Sempere 1991). In contrast, this group has been recognized in Argentina for nearly 150 years (Shockey et al. 2007). Most Bolivian mesotheriines are Miocene in age and all have been referred to two genera: Microtypotherium

Villarroel 1974b and Plesiotypotherium

Villarroel 1974a (but see

Flynn et al. 2002 regarding a specimen from Micaņa, Bolivia). Prior to the discovery of three new mesotheriines from the Santacrucian Chucal locality of Chile, these Bolivian genera were thought to be the basal-most members of the subfamily (Villarroel 1974a,

1974b,

1978;

Marshall et al. 1983;

Cerdeņo and Montalvo 2001).

Plesiotypotherium minus, the smallest species of the genus and the subject of this report, is known only from two described specimens: the holotype (a left mandible from Cerdas preserving the full dentition and isolated right i1 and p4;

Villarroel 1978) and a pair of mandibles from the late middle Miocene locality of Quebrada Honda (Croft 2007;

Figure 1).

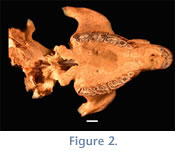

MacFadden et al. (1995, p. 8160) collected "about 50 dentitions, mostly Plesiotypotherium minus" from Cerdas, but this paper—which focused primarily on geology and tectonics—did not provide any detailed comparisons or descriptive data for the specimens. This UF collection includes both maxillae and mandibles and, as noted above, a well-preserved cranium (lacking only the anterior neurocranium, the nasal bones, and most of the dorsal portion of the skull;

Figure 2). Recently, DAC and colleagues from UF, UATF, and U. of Rochester returned to the Cerdas locality (see

Croft et al. 2009) and collected many additional mesotheriine specimens, including a partial skull with full dentition; these will also be evaluated in this report.

Plesiotypotherium minus, the smallest species of the genus and the subject of this report, is known only from two described specimens: the holotype (a left mandible from Cerdas preserving the full dentition and isolated right i1 and p4;

Villarroel 1978) and a pair of mandibles from the late middle Miocene locality of Quebrada Honda (Croft 2007;

Figure 1).

MacFadden et al. (1995, p. 8160) collected "about 50 dentitions, mostly Plesiotypotherium minus" from Cerdas, but this paper—which focused primarily on geology and tectonics—did not provide any detailed comparisons or descriptive data for the specimens. This UF collection includes both maxillae and mandibles and, as noted above, a well-preserved cranium (lacking only the anterior neurocranium, the nasal bones, and most of the dorsal portion of the skull;

Figure 2). Recently, DAC and colleagues from UF, UATF, and U. of Rochester returned to the Cerdas locality (see

Croft et al. 2009) and collected many additional mesotheriine specimens, including a partial skull with full dentition; these will also be evaluated in this report.

Some small mesotheriines from Nazareno have been referred to Plesiotypotherium based on general resemblance (Oiso 1991), but have not been described in detail; they have been considered to represent the smallest and oldest specimens of Plesiotypotherium (Oiso 1991) and may therefore be referable to P. minus. The dental dimensions reported by

Oiso (1991) indicate a rather consistent size range for most of the sample, other than an outlier that is smaller than the smallest and most basal mesotheriine, Eotypotherium chico (Croft et al. 2004). The Nazareno specimens were evaluated in our study using data from

Oiso (1991); we have not had the opportunity to view the material directly.

In addition to Plesiotypotherium, Microtypotherium choquecotense from the Choquecota locality is the only other mesotheriine from Bolivia. Until the discovery of the older Chucal fauna from Chile, this tiny mesotheriine was thought to be both the smallest and most primitive member of the subfamily (Villarroel 1974b). The holotype is a right maxilla bearing P4-M3 (and the alveolus for P3), and associated m2-m3 (Villarroel 1974b). Specimens from Cerdas (a posterior cranium, upper incisors, the lingual half of a left M2, and radius) also have been referred to Microtypotherium (Villarroel 1978).

Variation in dental morphology in Plesiotypotherium and Microtypotherium is not clearly understood. This is primarily due to a paucity of referred specimens and a relative absence of published measurements for those few specimens that have been referred to as recognized species.

Villarroel (1974a) noted that the sample of P. achirense from Achiri was highly variable, possibly indicating the presence of more than one species or sexual dimorphism, but did not explore this issue further. Other than a comparison of the Quebrada Honda specimen of P. minus with the holotypes of P. minus and P. achirense (Croft 2007), no metric comparisons between Plesiotypotherium holotypes and any other specimens have been published. This is surprising given that size is an important character for distinguishing species of mesotheriines, particularly when other dental characters (e.g., enamel sulci, lobe shape) are subtle or highly variable (Francis 1965;

Villarroel 1974a,

1974b;

Cerdeņo and Montalvo 2001;

Croft et al. 2004).

The phylogenetic relationships of P. minus are also unclear.

Villarroel (1974a) suggested that the Bolivian mesotheriines from Cerdas and Choquecota (Microtypotherium) were more primitive than Eutypotherium (from Argentina). He also proposed an anagenic mode of evolution for Bolivian mesotheriines with Microtypotherium as the basal-most form leading to Plesiotypotherium minus, then Plesiotypotherium achirense, and finally to Plesiotypotherium majus (Villarroel 1974a,

1974b,

1978). Testing this hypothesis requires assessing: 1) metric variation within and among these forms; 2) variation in discrete dental characters; and 3) the identity of Microtypotherium cf. M. choquecotense from Cerdas.

Croft et al. (2004) performed a cladistic analysis of dental and cranial characters for all known members of the subfamily, though Plesiotypotherium was coded at the generic level rather than as discrete species. Their results indicated that M. choquecotense (from Choquecota) was basal to other Bolivian taxa and all Argentine species (Croft et al. 2004).

The relative abundance of mesotheriine specimens from Cerdas presents an opportunity to evaluate the validity of P. minus and the proper generic designation of this species. As detailed below, our analyses indicate that two groups of specimens can be distinguished at Cerdas based on size and dental characters of the lower molars. Neither shares an exclusive relationship with Plesiotypotherium (i.e., P. achirense) and therefore should not be referred to this genus.