Angiosperm pollen grains from the Cuayuca Formation (Late Eocene to Early Oligocene), Puebla, Mexico

Angiosperm pollen grains from the Cuayuca Formation (Late Eocene to Early Oligocene), Puebla, Mexico

Article number: 18.1.2A

https://doi.org/10.26879/465

Copyright Paleontological Society, January 2015

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Submission: 27 February 2014. Acceptance: 19 December 2014

{flike id=1027}

ABSTRACT

Systematic descriptions and illustrations of the best preserved angiosperm pollen grains (Monocotyledonae or Liliopsida: n= 7 and Dicotyledonae or Magnoliopsida: n= 41) recovered from Cuayuca Formation (late Eocene-early Oligocene), Puebla State, Mexico are provided, some of them of chronostratigraphic importance ( Aglaoreidia pristina, Armeria, Bombacacidites, Corsinipollenites, Eucommia, Favitricolporites, Intratriporopollenites, Lymingtonia, Magnaperiporites, Malvacipollis spinulosa, Margocolporites aff. vanwijhei, Momipites coryloides, Momipites tenuipolus, Mutisiapollis, Ranunculacidites operculatus, and Thomsonipollis sabinetownensis ). Taxa identified from the Cuayuca Formation suggest local semiarid vegetation such as tropical deciduous forest, chaparral, grassland, and arid tropical scrub, in which angiosperms are one of the main representatives. Nevertheless, temperate taxa from Pinus forest and cloud forest were also registered from regional vegetation. It is noticeable that at the present time, such taxa are well represented in the vegetation of the Balsas River Basin, which would suggest the existence of this type of flora in the Cuayuca region since the Oligocene.

Elia Ramírez-Arriaga. Departamento de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Av. Universidad 3000, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 04510, México, Distrito Federal, elia@unam.mx.

Mercedes B. Prámparo. Centro Regional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas, Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Unidad de Paleopalinología, Mendoza, Argentina. mprampar@mendoza-conicet.gob.ar

Enrique Martínez-Hernández. Departamento de Paleontología, Instituto de Geología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Av. Universidad 3000, Ciudad Universitaria, C.P. 04510, México, Distrito Federal. emar@unam.mx

Keywords: systematic palynology; angiosperm pollen grains; Cuayuca Formation; Paleogene vegetation; Mexican Cenozoic basins

Final citation: Ramírez-Arriaga, Elia, Prámparo, Mercedes B., and Martínez-Hernández, Enrique. 2014. Angiosperm pollen grains from the Cuayuca Formation (Late Eocene to Early Oligocene), Puebla, Mexico. Palaeontologia Electronica 18.1.2A: 1-38. https://doi.org/10.26879/465

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2015/1027-angiosperm-pollen-cuayuca-fm

INTRODUCTION

The Cuayuca Formation was described by Fries (1966), who designated a Miocene-Pliocene age. Subsequently, palynostratigraphic research has allowed it to be re-assigned to a late Eocene-early Oligocene age based on the presence of some index taxa, such as Cicatricosisporitesdorogensis, Aglaoreidiapristina, Ephedripitesclaricristatus, Malvacipollisspinulosa, Margocolporites aff. vanwijhei, Momipitestenuipolus, Ranunculaciditesoperculatus, Polyadopollenites aff. pflugii, and Thomsonipollis sabinetownensis (Ramírez-Arriaga et al., 2006, 2008). The Cuayuca Formation is within the Balsas Group; it was deposited in central Mexican Tertiary basins generated through tectonic events (Silva-Romo et al., 2000). Currently, those Paleogene basins are distributed throughout the Mezcala-Balsas hydrological system (Fries, 1960) also known as the Balsas River Basin. The Cuayuca Formation yielded a diverse and well preserved terrestrial palynological assemblage obtained from nine outcrop sections in Puebla State, southern Mexico (Figure 1). The palynoflora studied includes gymnosperm and angiosperm pollen grains, as well as pteridophyte and bryophyte spores. Ramírez-Arriaga et al. (2005) published systematic descriptions of spores and gymnosperm pollen grains.

The Cuayuca Formation was described by Fries (1966), who designated a Miocene-Pliocene age. Subsequently, palynostratigraphic research has allowed it to be re-assigned to a late Eocene-early Oligocene age based on the presence of some index taxa, such as Cicatricosisporitesdorogensis, Aglaoreidiapristina, Ephedripitesclaricristatus, Malvacipollisspinulosa, Margocolporites aff. vanwijhei, Momipitestenuipolus, Ranunculaciditesoperculatus, Polyadopollenites aff. pflugii, and Thomsonipollis sabinetownensis (Ramírez-Arriaga et al., 2006, 2008). The Cuayuca Formation is within the Balsas Group; it was deposited in central Mexican Tertiary basins generated through tectonic events (Silva-Romo et al., 2000). Currently, those Paleogene basins are distributed throughout the Mezcala-Balsas hydrological system (Fries, 1960) also known as the Balsas River Basin. The Cuayuca Formation yielded a diverse and well preserved terrestrial palynological assemblage obtained from nine outcrop sections in Puebla State, southern Mexico (Figure 1). The palynoflora studied includes gymnosperm and angiosperm pollen grains, as well as pteridophyte and bryophyte spores. Ramírez-Arriaga et al. (2005) published systematic descriptions of spores and gymnosperm pollen grains.

There are several publications dealing with Mexican Cenozoic palynology (Graham, 1976; Martínez-Hernández et al., 1980; Tomasini-Ortíz and Martínez-Hernández, 1984; Palacios and Rzedowsky, 1993; Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1996, 1999; Graham, 1999), but taxonomic studies with detailed descriptions of Paleogene and Neogene pollen grains are lacking in most of those studies.

The present contribution deals with the taxonomy and systematics of selected angiosperm pollen grains (Monocotyledonae or Liliopsida and Dicotyledonae or Magnoliopsida) obtained from the Cuayuca Formation, some of them of chronostratigraphic importance. The Monocotyledonae (Liliopsida) pollen grains are represented by monosulcate and monoporate aperture types and Dicotyledonae (Magnoliopsida) pollen grains include colpate, colporoidate, colporate, porate, and inaperturate pollen types. This contribution constitutes one of the first taxonomic descriptions of angiosperm pollen grains recovered from the evaporites of the Cuayuca Formation, which provides useful information for a better understanding of the paleobiodiversity and distribution of the Mexican plant communities during the late Paleogene.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

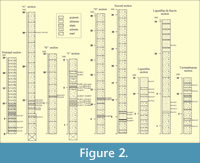

A total of 49 samples were collected from nine outcrop sections, with 21 samples bearing palynomorphs (Figure 2). All samples were processed through standard methods (HCI and HF). The slides obtained have been stored in the UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), at the Geology Institute Palynological Collection (IGLUNAM). Samples were examined with a Zeiss transmitted light microscope, and the photomicrographs were taken with a Sony digital camera. In order to highlight the morphology, some photographs were taken in phase-contrast. Coordinates of the illustrated specimens were provided, most of them using an England Finder (EF) slide. Total counts of taxa at the different sections studied are shown in Table.

A total of 49 samples were collected from nine outcrop sections, with 21 samples bearing palynomorphs (Figure 2). All samples were processed through standard methods (HCI and HF). The slides obtained have been stored in the UNAM (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México), at the Geology Institute Palynological Collection (IGLUNAM). Samples were examined with a Zeiss transmitted light microscope, and the photomicrographs were taken with a Sony digital camera. In order to highlight the morphology, some photographs were taken in phase-contrast. Coordinates of the illustrated specimens were provided, most of them using an England Finder (EF) slide. Total counts of taxa at the different sections studied are shown in Table.

Statistical Analysis

In order to determine vegetation types, taxa were classified by means of multivariate analysis via hierarchical clustering analysis, in which groups were defined using the Ward method with a Euclidian distance of 1.8; this was done using program R (Johnson, 2000). In addition, Constrained Cluster Analysis (CONISS) through the incremental sum of squares method was applied using the Tilia Graph program, in order to define paleopalynological changes in the Cuayuca Formation Mcy Member (Grimm, 1987). This analysis was also able to give information concerning the most representative elements in each paleocommunity.

The Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity (PAE)

Parsimony Analysis of Endemicity (Rosen, 1988; Morrone and Crisci, 1995; Ramírez-Arriaga et al., 2008, 2014) was used to compare the palynomorph diversity of Cuayuca Formation outcrop sections: 1) principal section; 2) section “A” (Cuay A); 3) section “B” (Cuay B); 4) section “F” (IzF); 5) section “H” (IzH); 6) second section (IzS); 7) Lagunillas section (Lag); 8) Lagunillas de Rayón section (LagRay); and 9) Tzompahuacan section (Tzo).

The WINCLADA data matrix from PAE analysis (Nixon, 2002) shows rows that correspond to outcrop sections and columns for palynomorphs, whose presence (1) or absence (0) in each section is indicated. In hierarchic grouping, sections were clustered according to the presence of taxa. NONA was used to carry out the parsimony analysis (Goloboff, 1993). The PAE analysis included a heuristic search with tree bisection and reconnection (TBR), branch swapping with 500 replications holding 10 trees per replication, and further expanding the memory to hold up to 10,000 trees. WINCLADA calculated three statistics that reflect the degree of conflict among data: a) Length=L; b) Consistency Index=CI; and c) Retention Index=RI. In the present work, clades are supported by the presence of palynomorphs, and unique occurrences are emphasized with black circles.

SYSTEMATIC PALAEONTOLOGY

A total of 114 taxa of angiosperm pollen grains were identified from the Cuayuca Formation (Ramírez-Arriaga et al., 2006). The Dicotyledonae group was the most representative and diverse, with 95 taxa. The Monocotyledonae showed a lower diversity of only 19 taxa. Because of the low number of specimens of each taxon present in the assemblage, the assignment to known or new species has been problematic. Thus, 48 taxa were classified only to the genus level, with open nomenclature at the species level (Appendix 1). These taxa are fully described, illustrated, presented as Monocotyledonae or Dicotyledonae, and are in alphabetical order: 41 of them are Dicotyledonae and seven Monocotyledonae, with the botanical affinities provided in Appendix 2. In general, scientific names have been cited according to a parataxonomic classification of fossil taxa. These diagnoses are based on Jansonius and Hills (1976) catalogue, as well as on other publications cited in the text. Only cases which show a clear affinity to a recent genus are cited as modern genus pollen types (e.g., Armeria sp.), using the natural classification system.

The classification down to family level and author names of orders and families follows the APG III (2009) and Cronquist (1981). In the case of some fossil genera of controversial botanical affinity, we gave the taxonomic range up to Class or Order rank. For each taxon, the distribution is given for different Mexican basins, and in North America and Europe, with the exception of some comparisons to Southern Hemisphere specimens. Descriptive terminology is based on El Ghazali (1990), Traverse (1988), and Punt et al. (2007).

Kingdom PLANTAE Haeckel, 1866

Division MAGNOLIOPHYTA Cronquist et al., 1966

Class LILIOPSIDA Cronquist et al., 1966

Genus AGLAOREIDIA Erdtman, 1960 emend. Fowler, 1971

Type species. Aglaoreidiacyclops Erdtman, 1960

Aglaoreidia pristina Fowler, 1971

Figure 3.7

Material. Sample Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Material. Sample Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular, spheroidal. Monoporate, pore with annulus 1.2 μm thick. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 μm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, brochi <0.8 μm near the aperture.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 24.8 μm; polar diameter 24 μm based on one measured specimen.

Other occurrences. Mexico - late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999). U.S.A. - late Eocene to early Oligocene, Gulf Coast (Frederiksen, 1980a, 1988). Europe - late Eocene to middle Oligocene, northeastern Europe (Krutsch, 1963); late Eocene, England (Fowler, 1971; Collison et al., 1981).

Genus ARECIPITES Wodehouse, 1933 emend. Nichols et al., 1973

Type species. Arecipitespunctatus Wodehouse, 1933 ex Potonié, 1958

Arecipites sp.

Figure 3.1

Material. Samples Pb-9138, Pb-9337, Pb-8896, Pb-8897, Pb-8899, Pb-8902, and Pb-8872, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, bilateral symmetry, amb oval, oblate. Monosulcate, sulcus extending full length of the grain and flared at ends. Exine tectate, columellate, 0.8 µm thick, microfoveolate with the arrangement of the columellae showing a very fine reticulate pattern.

Dimensions. Length 25.6-32 µm, width 13.6-22 µm, two specimens measured.

Comparisons. This species is very similar to Arecipitessubverrucatus (Barreda, 1997b) although differing in the smaller dimensions of our specimens. The Arecipites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation is not faintly scabrate as in A. pseudotranquilus (Nichols et al., 1973), nor as granulate as in A. pertusus (Elsik in Stover et al., 1966). Arecipites sp. described by Jarzen and Klug (2010) has a scabrate, foveolate to finely reticulate surface, a pattern very similar to the Mexican specimens, although differing in the dimensions (Florida specimens: 45-57 µm long axis; 30-38 µm short axis; Mexican specimens: 25-32 µm long axis, 13-22 µm short axis). The Mexican specimens are very similar to the Arecipites sp. (Christopher et al., 1980, plate 3, figures 1-2) from the Paleocene of Warm Springs, Georgia (Christopher et al., 1980).

Other occurrences. This genus has been reported in Mexican paleobasins from Eocene to Oligocene Simojovel, Chiapas (Tomasini-Ortiz and Martínez-Hernández, 1984). Reports of the occurrence of Arecipites -type pollen in the Caribbean region and in Texas (U.S.A.) are discussed in Jarzen and Klug (2010).

Genus LILIACIDITES Couper, 1953

Type species. Liliaciditeskaitangataensis Couper, 1953

Liliacidites sp. 1

Figure 3.2-3

Material. Samples Pb-8887, Pb-9136, Pb-9334, Pb-8897, Pb-9147, Pb-9138, Pb-9340, Pb-9343, Pb-8898, Pb-8872, and Pb-8896, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, bilateral symmetry, spherical outline. Monosulcate, sulcus extending full length of grain. Exine semitectate, collumelate, 0.8 µm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, reticulum consisting of large brochi of 2-3 µm, with small brochi at the intersections 0.4 µm and muri 0.5-0.8 µm wide .

Dimensions. Length 22.4-25.6 µm, width 13.6-20.8 µm, six specimens measured.

Comparisons. This taxon has a distinctive reticulum conformed by large brochi with small brochi at the intersections of the muri; this kind of reticulum is neither observed in Liliacidites sp.2 nor in Liliacidites sp.3 of the Cuayuca assemblage. Liliacidites sp.1 has a reticulum very similar to Liliacidites sp. F, illustrated in Plate 3 (Doyle and Robbins, 1975, figures 23-24) from the Raritan Formation (Cretaceous), Delaware, U.S.A. (Doyle and Robbins, 1975).

Other occurrences. Liliaceous-type pollen has been widely distributed throughout the world since the Cretaceous. In Mexico, records of the Liliacidites genus are known from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene of the San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Oligocene to Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); as well as the Neogene (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993).

Liliacidites sp. 2

Figure 3.6

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, bilateral symmetry, amb oval. Monosulcate. Exine semitectate, collumelate, 1 µm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, brochi 1.5-2 µm diminishing size toward the aperture and muri of 0.8 µm wide.

Dimensions. Length 32 µm, width 22 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Liliacidites sp. 2 has muri distinctively wider (0.8 µm) than those of Liliacidites sp.1 and Liliacidites sp. 3 of the Cuayuca assemblage. Liliacidites sp. 2 has a reticulum very similar to Liliacidites sp. 1 (Wingate, 1983, plate 2, figure 8) from Elko, Nevada (U.S.A), although Liliacidites sp. 1 has greater dimensions: 38 µm length and 30 µm width (Wingate, 1983).

Liliacidites sp. 3

Figure 3.8

Material. Sample Pb-8871, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, bilateral symmetry, amb oval. Monosulcate, aperture reaching the ends of the equator. Exine semitectate, collumelate, 1 µm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, reticulum consisting of large brochi of 1 µm with small brochi < 1 µm, both randomly distributed, muri < 0.5 µm.

Dimensions. Length 29-46 µm, width 17-28 µm, three specimens measured.

Comparisons. Liliacidites sp. 3 has thinner muri than those in Liliacidites sp. 1 and Liliacidites sp. 2 of the same association. This taxon resembles the specimen Liliaciditesquadrangularis illustrated by Roche and Schuler (1976) from Belgium (plate VII, figures 12-14), but L. quadrangularis has a thicker exine. Liliacidites sp. 3 from Cuayuca Formation closely resembles Liliacidites sp. A (Christopher et al., 1980, plate 3, figures 3-4) from Warm Springs, Georgia, U.S.A. (Christopher et al. , 1980).

Genus MONOCOLPOPOLLENITES Thomson and Pflug, 1953

Type species. Monocolpopollenites tranquillus (Potonié 1934) Thomson and Pflug, 1953

Monocolpopollenites aff. texensis Nichols et al., 1973

Figure 4.7

Material. Sample Pb-8872, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Material. Sample Pb-8872, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, bilateral symmetry, amb oval. Monosulcate. Exine tectate, the structure of the wall is difficult to discern, 0.8 µm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Length 32 µm, width 22.4 µm, one specimen measured.

Remarks. In a monographic discussion concerning monosulcate genera, Nichols et al. (1973) proposed that the shape of the sulcus differentiates the genus Monocolpopollenites from Arecipites. Arecipites includes monosulcate grains with a tapered sulcus, not expanded or gaping at the ends. Monocolpopollenites includes grains with flared or round-ended sulcus.

Comparison. M. aff. texensis (in this contribution) has the sulcus extending the entire long axis of the grain, with margins tending to overlap centrally, as in M. texensis. However, the Mexican specimen is larger (32 µm) than M. texensis (Nichols et al. 1973: 17–19 x 24–28 µm) and presents a psilate instead of scabrate exine.

Other occurrences. There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico. The genus has been reported from the US Gulf Coast (Frederiksen, 1980a) and in England (Wilkinson and Boulter, 1980).

Genus MONOPOROPOLLENITES Potonié, 1960

Type species. Monoporopollenites graminoides Potonié, 1960

Monoporopollenites sp.

Figure 3.5

Material. Samples Pb-9136, Pb-8870, Pb-9138, Pb-8896, Pb-9147, Pb-8872, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, heteropolar, radiosymmetric, amb subcircular. Monoporate, pore diameter 1.5-4 µm, with annulus of 1 to 2 µm thick. Exine tectate, collumelate, 1 µm thick, scabrate.

Dimensions. Diameter 15-39 µm, 19 specimens measured.

Comparison. Monoporopollenites sp. from Cuayuca Formation differs of Monoporopollenitesannulatus (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001) because the Mexican specimens are scabrate instead of psilate.

Fossil record. The genus Monoporopollenites has been widely reported in Mexico, the U.S.A., and Central and South America since the late Eocene (Tschudy, 1973; Leopold, 1974; Graham, 1975; Biaggi, 1978; Frederiksen, 1980; Graham, 1988, 1989, 1991; Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001; Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993; Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999, 2006).

Class MAGNOLIOPSIDA Cronquist et al., 1966

Genus BROSIPOLLIS Krutzsch, 1968

Type species. Brosipollis salebrosus (Pflug, 1953) Krutzsch, 1968

Brosipollis sp.

Figure 5.14-15

Material. Samples Pb-9340, Pb-8898, Pb-8872, Pb-9138, Pb-9340, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Material. Samples Pb-9340, Pb-8898, Pb-8872, Pb-9138, Pb-9340, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, subprolate. Tricolporate, endoapertures slightly protruding, lalongate 5 µm x 4 µm with converging transverse costae, meridional edges indistinct. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 µm thick, striate, fine striae-reticulate, about 0.4 µm thick.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 13-15 µm, polar diameter 15-27 µm, eight specimens measured.

Comparisons. Brosipollis sp. has similar dimensions, endoaperture, and ornamentation to Rugulitricolporites sp. 1 from the Eocene of California (Frederiksen et al., 1983, plate 23, figures 1-4); but, Brosipollis sp. from the Cuayuca Formation is striate-reticulate instead of simply striate.

Other occurrences. Records of the genus Bursera ( Brosipollis ) are known for the late Eocene - early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation of Puebla, Mexico (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Miocene (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993); and Pliocene (Graham, 1975). U.S.A. - Eocene of California (Frederiksen, 1989; Frederiksen et al. , 1983). This genus was described originally as being from the Malaysian Eocene (Muller, 1968).

Genus FAVITRICOLPORITES Sah, 1967

Type species. Favitricolporites eminens Sah, 1967

Favitricolporites sp.

Figure 3.10

Material. Sample Pb-9138, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Tricolporate syncolpate, colpi with margins 1 µm wide, extending nearly to the poles. Exine semitectate, collumelate, 1 µm thick, reticulate, homobrochate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 16 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Favitricolporites sp. 1 described by Frederiksen et al. (1983) is similar in ornamentation to the Favitricolporites from the Cuayuca Formation, although Favitricolporites sp. 1 is larger (Frederiksen et al., 1983: 36-50 µm). Unfortunately, no specimens were observed in meridional (equatorial) view, and for this reason the endoaperture could not be described.

Other occurrences. This taxon has been reported from the U.S.A. middle Eocene Mission Valley Formation (Frederiksen et al. , 1983). There are no previous records of the genus in Mexico.

Genus INTRATRIPOROPOLLENITES Thomson and Pflug, 1953 emend . Mai, 1961

Type species. Intratriporopollenites instructus (Potonié, 1931) Thomson and Pflug, 1953

Intratriporopollenites sp.

Figure 3.17

Material. Sample Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Triporate, planaperturate, pores annulate, annulus 1 µm thick. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.5 µm thick, microreticulate, homobrochate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 20 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Elsik and Dilcher (1974, plate 29, figures 91-92) reported a similar specimen as Bombacaceae, Sterculiaceae, Tiliaceae? from middle Eocene Claiborne Formation, Tennessee. Other similar Intratriporopollenites (Frederiksen, 1980a, plate 14, figure 17) and Tiliaepollenites (Tschudy and van Loenen, 1970, plate 5, figures 11a, 11b) were reported from upper Eocene, Jackson Group. Tilia was recovered from middle Eocene Kisinger Lake locality (Leopold, 1974: plate 44, figure 18) and Intratriporopollenitesceciliensis from the Eocene of California (Frederiksen, 1989, table 5, figures 2, 3). Intratriporopollenites differs from Bombacacidites because the later taxa is suprareticulate with the greatest diameter of the lumina at the poles, becoming gradually finer toward the apertures and in the intercolpial areas (Nichols, 2010).

Other occurrences. The genus has been reported in Mexico as Oligo-Miocene, Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); Miocene, Pichucalco, Chiapas (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993). This taxon has been identified in U.S.A., Tennessee (Elsik and Dilcher, 1974), Kisinger Lakes locality (Leopold, 1974), and California (Frederiksen, 1989).

Genus LYMINGTONIA Erdtman, 1960

Type species. Lymingtonia rhetor Erdtman, 1960

Lymingtonia sp.

Figure 4.10

Material. Samples Pb-9334 and Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spherical. Pericolpate, 12 costate colpi 7.9-19 µm long and 2.4-4 µm wide, with microverrucate on membrane. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 µm thick, microreticulate.

Dimensions. Diameter 28-31 µm, four specimens measured.

Comparisons. The Lymingtonia sp. described herein is smaller than L. rhetor (Erdtman, 1972: 50 µm), although both have perforations of similar dimensions: about 1.0 µm wide (Jansonius and Hills, 1976: card number 1562). L. cenozoica, described by Pocknall and Mildenhall (1984) from New Zealand, has smaller perforations (< 5 µm), a sparsely conate/spinulose ornamentation and raised crater-like punctae; in contrast, our specimens are microreticulate.

Other occurrences. This genus has been recovered in the U.S.A. - early Eocene of Tennessee (Elsik and Dilcher, 1974); late Eocene of Jackson Group, Mississippi and Alabama (Frederiksen, 1980a). Caribbean islands - middle Miocene of the Saramaguacán Formation, Cuba (Graham, 2000; Graham et al., 2000).

Genus MALVACIPOLLIS Harris, 1965

Type species. Malvacipollis diversus Harris, 1965

Malvacipollis spinulosa Frederiksen, 1983

Figure 5.12

Material. Sample Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular, spheroidal. Stephanoporate, pores annulate. Exine tectate, supraechinate, echinae solid, 1 - 1.2 µm in height, distributed homogeneously over the surface of pollen grain.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 23 (25) 27 µm based on three measured specimens.

Other occurrences. Mexico - late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999). U.S.A. - late Paleocene Silverado Formation, California (Gaponoff, 1984); Paleocene - Oligocene, South Carolina (Frederiksen, 1980b); late Eocene - early Oligocene of the Elko Formation, Nevada (Wingate, 1983); it was cited as Echiperiporites from the Eocene of Mississippi embayment (Tschudy, 1973); middle Eocene, San Diego, California (Frederiksen et al., 1983). Argentina -middle Miocene, Argentina (Barreda et al., 1998).

Genus RHOIPITES Wodehouse, 1933

Type species. Rhoipites bradleyi Wodehouse, 1933

Rhoipites aff. cryptoporus Srivastava, 1972

Figure 3.21-22

Material. Sample Pb-8890, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, prolate. Tricolporate, endoaperture circular 2 µm in diameter. Exine tectate, columellate, 1 µm thick, micropitted.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 15 µm, polar diameter 22 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. This pollen grain resembles a specimen illustrated by Jardine and Harrington (2008) from the Paleocene of Mississippi, U.S.A. It is characterized by its circular endoaperture and its subtectate-reticulate exine; but the specimen from Mississippi is larger (Jardine and Harrington, 2008: 29 µm polar diameter). Differs from R. cryptoporus, which is heterobrochate (Srivastava, 1972).

Other occurrences. Rhoipites has shown worldwide distribution since the late Cretaceous (Srivastava, 1972). R. cryptoporus has been recovered from the late Paleocene of Mississippi, U.S.A. (Jardine and Harrington, 2008) and Alabama (Srivastava, 1972). There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico.

Rhoipites sp.

Figure 4.8-9

Material. Samples Pb-9334 and Pb-8890, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, subprolate. Tricolporate, endoaperture lalongate 12x3 µm. Exine semitectate, columellate, 1 µm thick, reticulate, homobrochate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 22 µm, polar diameter 27 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. The Rhoipites sp. is distinguished by its homobrochate reticulum instead of the heterobrochate reticulum very evident in Rhoipiteslatus and R. subprolatus from the Eocene of Alabama, U.S.A. (Frederiksen, 1980a). A comparable form has been illustrated by Quattrochio et al. (2000) from the Paleogene of Argentina.

Other occurrences. Rhoipites has a worldwide distribution since Late Cretaceous. There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico.

Genus STRIATRICOLPORITES Van der Hammen, 1956 ex Leidelmeyer, 1966

Type species. Striatricolporites primulis Leidelmeyer, 1966

Striatricolporites sp.

Figure 5.8-9

Material. Samples Pb-9334, Pb-9340, Pb-8898, Pb-9138, Pb-8896, and Pb-9136, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, subprolate. Tricolporate, endoaperture lalongate with converging transverse costae, meridional edges indistinct. Exine semitectate, 0.8 µm thick, striate, striae 0.5 µm parallel to polar axis.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 16-21 µm, polar diameter 28-33 µm, five specimens measured.

Comparisons. Striatricolporitesdigitatus (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001) has similar dimensions to Striatricolporites sp. However, S. digitatus has a thicker exine (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001: 1 µm) and ectocolpi costate.

Other occurrences. Striatricolporites has been recovered in Mexico from the late Eocene to early Oligocene of Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999). Jaramillo and Dilcher (2001) reported Striatricolporites digitatus from the middle Paleocene of Colombia. Africa - Oligocene of Cameroon (Salard-Cheboldaeff, 1979). Type species from the Paleocene-Eocene of Guyana (Leidelmeyer, 1966).

Genus THOMSONIPOLLIS Krutzsch, 1960 emend. Elsik, 1968

Type species. Thomsonipollismagnificus (Thomson and Plug, 1953) Krutzsch, 1960

Thomsonipollissabinetownensis Elsik, 1968

Figure 5.19

Material. Sample Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Triporate, pores 5 x 4 μm, annulate, annulus 1 µm thick. Exine tectate, 0.5 µm thick, scabrate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 24.8 µm x 28 µm, one specimen measured.

Other occurrences. U.S.A. - Eocene of Gulf Coast (Elsik, 1974)

Order ASTERALES Lindley, 1833

Family ASTERACEAE Berchtold and Presl, 1820

Genus MUTISIAPOLLIS Macphail and Hill, 1994

Type species. Mutisiapollis patersonii Macphail and Hill, 1994

Mutisiapollis sp.

Figure 5.7, 5.11

Material. Sample Pb-8872, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, prolate. Tricolporate, endoaperture lalongate, 12 µm x 4.8 µm. Exine tectate, columellate, clearly stratified with two layers, 3.2 µm thick in the mesocolpi, and 2.4 µm in the apocolpi, supramicroechinate, echinae <0.5 µm high .

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 24.8 µm, polar diameter 38.4 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. M. viteauensis Barreda et al., 1998 from the Miocene “Serie del Yeso” of Argentina has a thicker exine (Barreda et al., 1998: 3.5 to 6 µm) and spines less than 1 µm high. However, Mutisiapollis sp. from the Cuayuca Formation has lalongate endoapertures with dimensions similar to those of M. viteauensis.

Other occurrences. There are no records of this taxon in Mexico. Mutisieae pollen grains have been recovered from the Miocene Gatun Formation, Panamá (Graham, 1990a) and in Argentina from the Miocene of San Juan Province (Barreda et al., 1998).

Genus TUBULIFLORIDITES Cookson, 1947 ex Potonié, 1960

Type species. Tubulifloridites antipodicus Cookson, 1947 ex Potonié, 1960

Tubulifloridites sp.

Figure 5.17

Material. Samples Pb-9138, Pb-9340, Pb-8896, Pb-8897, Pb-8871, Pb-9141, Pb-8868, Pb-8869, Pb-9136, Pb-8870, and Pb-9147, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Tricolporate. Exine tectate, columellate, 4 µm thick, cavate, echinae columellate at the base, conical, 4 µm long x 3 µm wide at the base, distance between echinae 4-5 µm.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 20-23 µm, three specimens measured.

Comparisons. Compositae specimens have been recovered from the Monterrey Formation (Miocene), although they are larger (Srivastava, 1984: 40 µm) with echinae 6 µm high (Srivastava, 1984).

Other occurrences. Compositae specimens have been reported in Mexico - Eocene of Baja California (Cross and Martínez-Hernández, 1980). U.S.A.- late Miocene Valentine Formation, Nebraska (MacGinitie, 1962). Originally described from the Tertiary of Australia (Cookson, 1947) and Germany (Potonié, 1960).

Order CARYOPHYLLALES Bentham and Hooker, 1862

Family AMARANTHACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus CHENOPODIPOLLIS Krutzsch, 1966

Type species. Chenopodipollis multiplex (Weyland and Pflug, 1957) Krutzsch, 1966

Chenopodipollis sp.

Figure 3.9

Material. Samples Pb-9147, Pb-9136, Pb-9343, Pb-8869, Pb-8872, Pb-9138, Pb-8898, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spheroidal. Periporate, 22 pores 2.5-3 µm wide, annulate, annulus 1.5 µm thick. Exine tectate, collumelate, 1 µm thick, with microreticulate pattern.

Dimensions. Diameter: 16-25 µm, 10 specimens measured.

Comparison. Our specimens have dimensions and annulus similar to Chenopodipollismultiplex (Bebout, 1980). However, the exine of the Chenopodipollis sp. from the Cuayuca Formation shows a microreticulate pattern, and this trait is not observed in C.multiplex.

Other occurrences. This genus has been reported across the globe since the Paleocene. In Mexico there are records of this genus from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation, Baja California Sur (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Oligocene-Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); and Neogene (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993; Graham, 1975).

Family NYCTAGINACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus MAGNAPERIPORITES González-Guzmán, 1967

Type species. Magnaperiporites spinosus González-Guzmán, 1967

Magnaperiporites sp.

Figure 4.16

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spheroidal, periporate. Pores circular or subcircular, 3 µm in width, distance between pores from 8 to 10 µm, pattern areolate. Exine tectate collumelate, 4 µm thick without echinae, perforate supraechinate, echinae 1 µm high.

Dimensions. Diameter 65 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Magnaperiporites sp. has smaller dimensions than M. spinosus illustrated by González-Guzmán (1967) and Salard-Cheboldaeff (1979). González-Guzmán (1967) gave a diameter for M. spinosus of 90 to 105 µm, with an exine thickness of 13.5 µm. Salard-Cheboldaeff (1979) reported M. spinosus with a diameter of 92-93 µm and exine 13 µm thick.

Other occurrences. This is the first mention of the genus in Mexican fossil microfloras. Magnaperiporites spinosus has been recovered from the Oligocene of Cameroon, Africa (Salard-Cheboldaeff, 1979) and from the early to middle Eocene of Colombia (González-Guzmán, 1967).

Family PLUMBAGINACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus ARMERIA Willdenow, 1809

Type species. Armeria vulgaris Willdenow, 1809

Armeria sp.

Figure 3.11

Material. Samples Pb-9340, Pb-8898, Pb-8872, Pb-9137, Pb-9334, and Pb-8896, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular, prolate spheroidal. Tricolpate. Exine semitectate, columellate, 5 µm thick, reticulate, supramicroequinate, muri with large columellae of 4.2 µm and lumina 3.6-5.6 µm in diameter.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 37-40 µm, polar diameter 35-45 µm, two specimens measured.

Remarks. Armeria is included in Plumbaginaceae. This family is cosmopolitan, although its distribution center is the Mediterranean (Papanicolaou and Kokkini, 1982).

Comparison. The Armeria pollen type is very similar to the Armeria sp. recovered from the Monterey Formation (Miocene) phosphatic facies, California (Srivastava, 1984). Both have similar dimensions and ornamentation.

Other occurrences. Mexico - late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999). U.S.A. - Miocene of the Monterey Formation, California (Srivastava, 1984).

Order FABALES Bromhead, 1838

Family FABACEAE Lindley, 1836

Fabaceae pollen type 1

Figure 3.12-13

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, subprolate. Tricolporoidate. Exine semitectate, columellate, 1.2 µm thick, microreticulate, lumina 0.5 µm, muri 0.5 µm .

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 26 µm, polar diameter 32 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Fabaceae pollen type 1 differs from Fabaceae pollen type 2 and Fabaceae pollen type 3 (in this paper) because it is tricolporoidate and microreticulate whereas Fabaceae pollen type 2 and Fabaceae pollen type 3 are tricolporate and not reticulate.

Other occurrences. Leguminosae fossil pollen grains have been recovered from late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999).

Fabaceae pollen type 2

Figure 3.18-20

Material. Sample Pb-8890, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, prolate. Tricolporate, ectoaperture reaching apocolpia, endoaperture lolongate 3 x 7 µm. Exine tectate, columellate, 1 µm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 18µm, polar diameter 30 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. The colporate and tectate - psilate condition makes this specimen different from Fabaceae pollen type 1, and Fabaceae pollen type 3 (of the same association, described in this paper).

Other occurrences. Fabaceae fossil pollen grains have been recovered from late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999).

Fabaceae pollen type 3

Figure 4.13

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Tricolporate. Exine tectate, 1µm thick, foveolate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 25 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Observations on morphology was only achievable in polar view, thus it was not possible to describe the endoaperture. Nevertheless, it differs from other Fabaceae described in this contribution, because it is tectate-foveolate.

Other occurrences. Fabaceae fossil pollen grains ( Caesalpinia, Acacia, and Mimosa ) have been recovered from late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999).

Genus MARGOCOLPORITES Ramanujam, 1966 ex Srivastava, 1969 emend. Pocknall and Mildenhall, 1984

Type species. Margocolporites tsukadai Ramanujam 1966 ex Srivastava, 1969

Margocolporites aff. vanwijhei Germeraad et al., 1968

Figure 4.6

Material. Samples Pb-9334(1) and Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Tricolporate, exoapertures present colpal membrane with fine baculae and margo 1 µm thick, endoaperture lolongate 2.4 µm X 5.6 µm. Exine subtectate, collumelate, 1.2 µm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, lumina 0.8- 1.5 µm, simplicolumelate muri.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 34.3 (38) 44 µm, polar diameter34 µm, four specimens measured.

Other occurrences. Mexico - Oligocene San Gregorio Formation, Baja California Sur (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006). Originally described from the Paleogene of the Caribbean region and Nigeria (Germeraad et al., 1968). South America - late Oligocene to Miocene Chenque Formation (Barreda, 1997c); early Miocene Chinches Formation (Ottone et al., 1998); and middle Miocene “Serie el Yeso,” Argentina (Barreda et al., 1998).

Margocolporites sp.

Figure 4.4-5

Material. Sample Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Tricolporate, colpi with membrane bearing fine bacula. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 µm thick, reticulate, heterobrochate, lumina 1-2 µm.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 45 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. This taxon is similar to Margocolporites sp. 2 from central Colombia (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001); but, Margocolporites sp. 2 is larger than Margocolporites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation. Margocolporites sp. (this work) has a larger equatorial axis and larger brochi than M. vanwijhei (Germeraad et al., 1968). The diameter of the endoaperture is almost equal to the width of the ectoaperture in the Margocolporites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation. The diameter of the endoaperture is smaller than the width in M. vanwijhei (Macphail, 1999; Eisawi and Schrank, 2008).

Other occurrences. The genus Margocolporites has been recovered from late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation, Baja California Sur (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006). M. vanwijhei has been recovered from middle Paleogene of central Colombia (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001); Germeraad et al. (1968) reported this species from late Eocene of Nigeria and in the Caribbean region Graham (2010) reported it from Eocene to the present time. It has also been recovered from the Murray Basin of southeastern Australia (Macphail, 1999) and southeastern Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008).

Genus POLYADOPOLLENITES Thomson and Pflug, 1953

Type species. Polyadopollenites multipartitus Thomson and Pflug, 1953

Polyadopollenites sp.1

Figure 5.2-3

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Polyad with 16 pollen grains: eight central grains and eight peripheral. Inaperturate. Exine atectate, 0.8-1.6 µm thick, regulate.

Dimensions. Polyad 48.8 µm x 46.4 µm. Monad: Equatorial diameter 16-20 µm, polar diameter 11.2 -14.4 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Polyadopollenites sp. 1 is distinguished by its suprarrugulate exine instead of a psilate tectum in Acaciapollenites from late Oligocene of New Zealand (Pocknall and Mildenhall, 1984). Polyadopollenites sp. 1 presents similar ornamentation to Polyadopollenitesmulleri (Cavagnetto and Guinet, 1994); however, Polyadopollenites sp. 1 is not as big as P. mulleri (Cavagnetto and Guinet, 1994: 65-72 µm). Furthermore, P. mulleri from the Oligocene of Spain has porate monads (Cavagnetto and Guinet, 1994).

Other occurrences. This genus has been recovered in Mexico from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation, Baja California Sur (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Oligo-Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); Neogene (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993). Central America - early Miocene La Culebra Formation, Panamá (Graham, 1988). Caribbean islands- Oligocene San Sebastián Formation, Puerto Rico (Graham and Jarzen, 1969). Originally described from the Eocene-Oligocene in Germany (Thomson and Pflug, 1953).

Polyadopollenites sp. 2

Figure 5.1

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Polyad with 16 pollen grains: eight central grains and eight peripheral. Syncolpate. Exine tectate columellate, 0.8-1.6 µm thick, foveolate.

Dimensions. Polyad 36.8 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Polyadopollenites sp. 2 has distinctively syncolpate, tectate and foveolate monads; in contrast, Acaciapollenites has inaperturate, tectate and psilate monads (Pocknall and Mildenhall, 1984). This taxon does not have a superficial reticulum as Polyadopollenitescooksonii (Cavagnetto and Guinet, 1994); furthermore, Polyadopollenites sp. 2 has syncolpate apertures instead of subsidiary apertures.

Other occurrences. Polyadopollenites sp. 2 shows the same geographic pattern as Polyadopollenites sp. 1.

Family POLYGALACEAE Hoffmannsegg and Link, 1809

Genus POLYGALACIDITES Sah and Dutta, 1966

Type species. Polygalacidites clarus Sah and Dutta, 1966

Polygalacidites sp.

Figure 5.16

Material. Sample Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, subprolate. Stephanocolporate, endoaperture lalongate with costae. Exine atectate, 1.2 µm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 11 µm, polar diameter 20 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. This taxon differs from the Polygalacidites sp. from the Neogene of southeastern Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008) as the latter has more numerous and larger ectoapertures than the Polygalacidites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation. Nevertheless, both taxa have almost the same polar diameter.

Other occurrences. Mexico - late Eocene - early Oligocene (Martínez-Hernández, 1999), Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006). Originally described from Paleogene in Assam, India (Sah and Dutta, 1966).

Order FAGALES Engler, 1892

Family CASUARINACEAE Brown, 1814

Genus CASUARINIDITES Cookson and Pike, 1954

Type species. Casuarinidites cainozoicus Cookson and Pike, 1954

Casuarinidites sp.

Figure 3.4

Material. Samples Pb-9337, Pb-9340, Pb-8898, Pb-9141, Pb-9147, Pb-9136, Pb-9339, and Pb-8896, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Triporate, angulaperturate, aspidate pores, annulate, annulus with a 5.6 μm diameter. Exine tectate, granulate, 1.2 μm thick, scabrate. The granular infratectal structure gives a microreticulate pattern.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 26-37 µm, two specimens measured.

Comparisons. The size of the Casuarinidites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation is similar to that of C. granilabrata described by Srivastava (1972); however the exine of C. granilabrata is 2 µm thick.

Other occurrences. This genus has been reported in Mexico from the Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Oligo-Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978). U.S.A. - Miocene, Massachussets (Frederiksen, 1984); Paleocene, Alabama (Srivastava, 1972).

Family JUGLANDACEAE de Candolle ex Perleb, 1818

Genus MOMIPITES Wodehouse, 1933

Type species. Momipites coryloides Wodehouse, 1933

Momipites coryloides Wodehouse, 1933

Figure 4.12

Material. Samples Pb-9138’(1), Pb-9334(4) and Pb-9340(2), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Triporate, equidistant zonate pores. Exine tectate, 1 µm thick with uniformly spaced spinules.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 14 (17.8) 20 µm, five specimens measured.

Other occurrences. Mexico - late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006); Oligo-Miocene of Chiapas (Langenheim et al., 1967). U.S.A. - late Cretaceous to Paleocene, Colorado (Newman, 1965); late Paleocene, South Carolina (Van Pelt et al., 2000); late Eocene, Yazoo Clay, Mississippi (Tschudy and van Loenen, 1970); late Eocene, Mississippi and Alabama (Frederiksen, 1980a); Paleocene - late Eocene, South Carolina (Frederiksen, 1980b); Eocene, Mississippi embayment (Tschudy, 1973); Miocene, Massachusetts (Frederiksen, 1984); early Eocene, Tennessee (Elsik and Dilcher, 1974). Central America - Oligocene San Sebastión Formation, Puerto Rico (Graham and Jarzen, 1969); Eocene Gatuncillo Formation, Panamá (Graham, 1985); early Miocene Cucaracha Formation and La Boca Formation (Graham, 1988); Mio-Pliocene of Haiti (Graham, 1990b). Europe - Eocene, England (Wilkinson and Boulter, 1980).

Momipites tenuipolus Anderson, 1960

Figure 4.11

Material. Samples Pb-8872(2), Pb-8898(3) and Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Triporate. Exine tectate, psilate, 0.8 µm thick with a polar thinning.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 16.8 (17.3) 18 µm, based upon three measured specimens.

Other occurrences. U.S.A. - early Paleogene, San Juan Basin, New Mexico (Anderson, 1960); late Paleocene Silverado Formation, California (Gaponoff, 1984); Paleocene, Virginia (Frederiksen, 1979, 1998); early Eocene, Gulf Coast (Frederiksen, 1980b).

Order GARRYALES Lindley, 1846

Family EUCOMMIACEAE Engler, 1907

Genus EUCOMMIA Oliver, 1890

Type species. Eucommia ulmoides Oliver, 1890

Eucommia pollen type

Figure 3.16

Material. Samples Pb-9138, Pb-8898, Pb-9340, Pb-8896, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular, subprolate. Tricolporoidate, with two large colpi: one measuring 24 μm long and a smaller one 17.6 µm long. Exine atectate, 0.8 - 1 µm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 17-30 µm, polar diameter 22-35 µm, 13 specimens measured, five specimens measured.

Comparison. Eucommia sp. from the Cuayuca Formation has similar dimensions to E. ? leopoldae (Frederiksen et al. , 1983) and the Eucommia type (Frederiksen, 1988), but differs from both because they are tricolporate whereas the Eucommia herein described is distinctively tricolporoidate as seen in the Eucommia described by Erdtman (1972). It is also similar to Eucommia cf. E. ulmoides illustrated by Leopold (1974, plate 39, figure 13) and Wingate (1983, plate 2, figure 10).

Other occurrences. This genus was recorded in Mexico from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene of the San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006). U.S.A. - middle Eocene of Kisinger, Wyoming (Leopold, 1974); Eocene, Nevada (Wingate, 1983); early Eocene into middle Eocene, Gulf Coast (Frederiksen, 1988); middle Eocene, Hominy Peak Formation, San Diego, California (Frederiksen, 1983); Eocene, Teton Range, Wyoming (Love et al. , 1978); late Oligocene of Florissant Formation, Colorado (Leopold and Scott, 2001).

Order GENTIANALES Lindley, 1833

Family APOCYNACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus LANDOLPHIA Palisot de Beauvois, 1806

Type species. Landolphia owariensis Palisot de Beauvois, 1806

Landolphia pollen type

Figure 5.4

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, oblate spheroidal. Tricolporate, endoaperture with costae converging with meridional edges of endoapertures indistinct (El Ghazali, 1990). Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8-1 µm thick, reticulate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 27-33 µm, polar diameter 27-34 µm, two specimens measured. Equatorial diameter in polar view 27-29 µm, two specimens measured.

Comparisons. Landolphia comorensis Benth. and Hook has similar breviectoapertures as the Landolphia pollen type from Cuayuca Fm., although L. comorensis has endoapertures with transverse converging edges and indistinct meridional edges (Erdtman, 1972). The Landolphia pollen type herein described has endoapertures with converging transverse costae and indistinct meridional edges.

Other occurrences . This is the first report of the genus in Mexican fossil associations. Apocynaceae pollen grains have been reported from late Eocene to early Miocene from Cameroon (Salard-Cheboldaeff, 1981).

Family RUBIACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus SABICEA Aublet, 1775

Type species. Sabicea cinerea Aublet, 1775

Sabicea pollen type

Figure 5.20

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Triporate, lolongate pore. Exine semitectate, columellate, 2 µm thick, microreticulate, simplicolumellate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 27 μm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Pollen grains of the genus Sabicea, with finely reticulate exine and dimensions ranging from 32 to 36 μm, have been reported for the Miocene of Panama (Graham, 1987); however, the Sabicea pollen type recovered from the Cuayuca Formation is smaller (27 μm in equatorial diameter).

Other occurrences. Central America - early Miocene La Culebra Formation, Panama (Graham, 1987). There are no previous records of this genus in Mexico.

Order MALPIGHIALES Martius, 1835

Family EUPHORBIACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus CLAVAINAPERTURITES Hammen and Wymstra, 1964

Type species. Clavainaperturitesclavatus Hammen and Wymstra, 1964

Clavainaperturites sp.

Figure 4.14

Material. Sample Pb-9147, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spheroidal. Inaperturate. Exine tectate, 2.4 µm thick, sculture baculate with crotonoid pattern showing groups of five to six supratectal bacula.

Dimensions. Diameter 55 x 52 µm, one specimen measured .

Comparisons. Clavainaperturites sp. is very similar to the C. cf. clavatus (35 µm) from the Nuer Formation, Southeast Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008), although the specimen from the Cuayuca Formation is larger than the taxon from Sudan.

Other occurrences. There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico. This genus has been reported in the Paleocene of Southeast Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008); and in the Oligocene of British Guyana (Van der Hammen and Wymstra, 1964).

Genus GLYCYDENDRON Ducke, 1922

Type species. Glycydendron amazonicum Ducke, 1922

Glycydendron pollen type

Figures 3.14-15

Material. Sample Pb-9137, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb circular. Tricolpate, colpi with irregular margin. Exine intectate, 1.2-1.5 µm thick, echinate, spines 1.2-2 µm high are very thick at their bases in contrast with the thin flexible apices.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 31 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Glycydendron pollen type is intectate, echinate, and similar to the specimen described from the Miocene Uscari Formation (Graham, 1987), but it is of smaller dimensions. In contrast, the Glycydendron pollen type from the Cuayuca Formation has echinae with flexible apices which are thinner than those described by Graham (1987) from the Miocene of Costa Rica.

Other occurrences. Central America - Miocene Uscari Formation, Costa Rica (Graham, 1987). There are no previous records of the genus in Mexico.

Family LINACEAE de Candolle ex Perleb, 1818

Genus LINUM Linnaeus, 1753

Type species. Linum usitatissimum Linnaeus, 1753

Linum pollen type

Figure 4.15

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb subcircular. Tricolpate, the broad and large colpi make a small polar area. Exine semitectate columellate, 3 µm thick, microreticulate to striate, supragemmate, gemmae 2-3.5 µm in diameter, distributed irregularly over the surface of the grain.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 48-53 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Tricolpate pollen grain characterized by large size (Wingate, 1983: 44 x 49 µm) and gemmate ornamentation has been reported from the Elko Formation (Wingate, 1983, plate 2, figure 12). The tricolpate pollen type 1 from the Elko Formation is not semitectate microreticulate like the Linum pollen type from the Cuayuca Formation, and has a thinner exine.

Other occurrences. This is the first mention of the genus in the Mexican fossil record. This taxon is also recorded from the European middle Eocene to early Oligocene, Ebro Basin, Spain (Cavagnetto and Anadón, 1996).

Family MALPIGHIACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus MALPIGHIACEOIDITES Takahashi and Jux, 1989

Type species. Malpighiaceoidites periporifer Takahashi and Jux, 1989

Malpighiaceoidites sp.

Figures 5.6, 5.10

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spheroidal. Perisyncolporate, six to eight pores distributed irregularly and joined with colpi. Exine atectate, 1.5-2 µm thick, supraverrucate, verrucae irregular supratectal, 0.5-4 µm wide.

Dimensions. Diameter 25 (29.9) 33.6 µm, five specimens measured.

Comparisons. The Malpighiaceoidites sp. has pores connected by thin colpal bands, like the Type A described by Martin (2002); nevertheless, the Malpighiaceoidites sp. exhibits verrucae bigger than those presented by Type A of Martin (2002). Malpighiaceae specimens recovered in Central America by Graham (1985, 1988, 1989, 1990b) are different from those of the Cuayuca Formation. Perisyncolporites pokornyi reported from the Miocene of Venezuela (Lorente, 1986) and from the Río Turbio Formation (Eocene) from Argentina (Fernández et al., 2012) has a thicker exine without the distinctive verrucae present in the Cuayuca Formation specimen.

Other occurrences. The genus Malpighiaceoidites has been recovered only from the Miocene of Venezuela (Lorente, 1986), Paleocene of São Paulo, Brazil (Lima et al., 1991), Eocene of Argentina (Fernández et al., 2012), and Tertiary rocks from southeastern Australia (Martin, 2002).

Genus PERISYNCOLPORITES Germeraad et al., 1968

Type species. Perisyncolporites pokornyi Germeraad et al., 1968

Perisyncolporites sp.

Figure 5.5

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, apolar, radiosymmetric, spheroidal. Perisyncolporate, colpi with one or two endoapertures with irregular distribution, ora 2.5-4 µm in diameter, with costae. Exine tectate, 0.8-1 µm thick, suprarrugulate.

Dimensions. Diameter 34.4 µm x 32 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. This taxon resembles Perisyncolporitespokornyi from the middle Eocene of Florida, U.S.A. (Jarzen et al., 2010), although P. pokornyi has a thicker exine (Jarzen et al., 2010: 2.5 - 3 µm) and a smaller size (23-26 µm).

Other occurrences. U.S.A. - Middle Miocene, Florida (Jarzen and Klug, 2010). This genus has also been reported from the Paleogene of the Caribbean region and Nigeria (Germeraad et al. , 1968; Graham, 1990b) and the Paleogene of South America (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001).

Order MALVALES Lindley, 1833

Family MALVACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus BOMBACACIDITES Couper, 1960

Type species. Bombacaciditesbombaxoides Couper, 1960

Bombacacidites sp.

Figure 3.23

Material. Samples Pb-9334 and Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb tringular obtuse. Tricolporate, apertures interangular with exinal thickenings. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 μm thick, reticulate, heterobochate, apocolpial lumina of 1.6 μm are larger than mesocolpial lumina <0.8 μm.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 21.2 µm, based on one measured specimen.

Comparisons. The Bombacacidites sp. (in this contribution) is similar in size (16-20 µm) to Bombacacidites sp. 2 in Frederiksen (1988), although the Bombacacidites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation has wider brochi (0.8 - 1.6 µm) than Bombacacidites sp. 2 from the eastern Gulf Coast (Frederiksen, 1988: 0.5 - 1 µm). The specimen herein studied is also similar in the thickness of the exine and the width of the luminae at apocolpia to Bombacacidites sp. 2 described by Jaramillo and Dilcher (2001) from the middle Paleogene of Colombia, but differs in having a smaller equatorial diameter (Bombacacidites sp. of Cuayuca: 21.2 µm; Bombacacidites sp. 2: 33 to 40 µm). Another similar specimen to the Bombacacidites sp. from the Cuayuca Formation was described as middle Eocene at the Kissinger Lakes locality (Leopold, 1974, plate 45, figures 2-3).

Other occurrences. This genus has been recorded in Mexico from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation, Puebla (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999). U.S.A. - middle Eocene, San Diego, California (Frederiksen et al. , 1983); Eocene and Eocene-Oligocene of the Gulf Coast (Elsik, 1974; Frederiksen, 1988); middle Eocene, Kisinger, Wyoming (Leopold, 1974); middle Eocene from Pine Island, Florida, U.S.A. (Jarzen and Klug, 2010).

Order MYRTALES Lindley, 1833

Family ONAGRACEAE Jussieu, 1789

Genus CORSINIPOLLENITES Nakoman, 1965

Type species. Corsinipollenites oculus-noctis (Thiergart, 1940) Nakoman, 1965

Corsinipollenites sp. 1

Figure 4.1

Material. Samples Pb-9343, Pb-9340, and Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Triporate, annulate, annulus 7 μm thick, pores aspidate with granulate structure. Exine tectate, 1-1.6 μm thick, psilate, with microreticular endopattern.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 24-38.4 µm, four specimens measured.

Comparisons. Corsinipollenites. sp. 1 (in this paper) shows smaller dimensions and more aspidate pores compared to Corsinipollenites sp. 2 and Corsinipollenites sp. 3 of the Cuayuca assemblage. Corsinipollenites sp.1 has a more protruding pore and annuli thicker than those reported by Jaramillo and Dilcher (2001) which have annulus 2 μm thick, as well as that recovered from middle Eocene of Florida, with annulus 2-4 μm wide (Jarzen and Klug, 2010).

Other occurrences. In Mexico, the genus is reported to be from late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 2006). Jaramillo and Dilcher (2001) reported Corsinipollenites in the Paleocene of Colombia; it is also mentioned in the Paleocene of Merida Andes, western Venezuela (Pocknall and Jarzen, 2009) and in the early to middle Eocene from Pine Island, Florida (Jarzen and Klug, 2010) and Oligocene of Germany (Thiergart, 1940). More data on the distribution of this genus in the U.S.A. and northern South America is in Jarzen and Klug (2010).

Corsinipollenites sp. 2

Figure 4.3

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular.Triporate, pores aspidate. Exine tectate, 0.8 μm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 32.8 x 71.2 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Corsinipollenites sp. 2 is different from Corsinipollenites sp. 1 and Corsinipollenites sp. 3 of the same association, because it is larger, with a thinner exine and pores that are not as aspidate as in the other species of Corsinipollenites described in this contribution. This taxon is larger and has a thinner exine than Corsinipollenitesatlantica from Argentina (Barreda and Palamarczuk, 2000b) and Corsinipollenites cf. psilatus from the Melot Basin, southeast Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008).

Corsinipollenites sp. 3

Figure 4.2

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb triangular. Triporate, pores aspidate. Exine tectate, granulate, 0.8-1 μm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 41-50 µm, three specimens measured.

Comparisons. This species of Corsinipollenites exhibits a characteristic pore with evident granulate structure. Although granulate structure is present in Corsinipollenites sp. 1 and Corsinipollenites sp. 2, more aspidate pores are present in Corsinipollenites sp. 1; Corsinipollenites sp. 2 presents less aspidate pores than the other two species described. Corsinipollenites sp. 3 has similar dimensions and annulus thickness to Corsinipollenitesatlantica described from the Argentinian Oligocene-Miocene by Barreda and Palamarczuk (2000b); nevertheless, the exine of C. atlantica is thicker. This taxon closely resembles Corsinipolleites cf. psilatus from the Melot Basin, southeast Sudan (Eisawi and Schrank, 2008).

Order RANUNCULALES Lindley, 1833

Genus RANUNCULACIDITES Van der Hammen, 1956 ex Van der Hammen and Wijmstra, 1964

Type species. Ranunculacidites operculatus (Van der Hammen and Wijmstra, 1964) Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001

Ranunculacidites cf. communis Sah, 1967

Figure 5.13

Material. Samples Pb-9334 and Pb-9340, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, oblate spheroidal. Tricolporate, pantoperculate. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 μm thick, microreticulate, brochi 0.8 μm.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 23 µm, polar diameter 23 µm, one specimen measured.

Comparisons. Ranunculaciditescommunis from the late Neogene of Africa (Sah, 1967) differs from R. operculatus from the middle Miocene of Florida (U.S.A.) in having a fine reticulum instead of a psilate exine (Jarzen and Klug, 2010). Ranunculaciditescommunis (Sah, 1967) differs from R. cf. communis by having shorter colpi and a thick plug pontoperculum.

Other occurrences. There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico. Ranunculaciditesoperculatus has been recovered from the middle Miocene of Florida (Jarzen and Klug, 2010) and from the Paleogene of central Colombia (Jaramillo and Dilcher, 2001).

Ranunculacidites operculatus

Figure 5.21

Material. Sample Pb-9334(4), Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb oval triangular. Tricolpate, pontoperculate. Exine tectate, 0.8 μm thick, psilate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 20 µm based on one measured specimen.

Other occurrences. Mexico - Oligocene to Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); Pliocene of Veracruz (Graham, 1975). Central America - early Miocene La Culebra Formation (Graham, 1988); early Miocene of Uscari, Costa Rica (Graham, 1987); Pleistocene of Panamá (Bartlett and Barghoorn, 1973); Pleistocene of El Salvador and Guatemala (Tsukada and Deevey, 1967); early Miocene La Boca Formation, Panamá (Graham, 1989). Carribean islands - Oligocene of Puerto Rico (Graham and Jarzen, 1969); late Miocene to Pliocene of Haiti (Graham, 1990b). South America - Eocene and Miocene of Venezuela (Lorente, 1986); Oligocene to early Miocene of Venezuela (Rull, 2001, 2003); middle Eocene of Tibu, Colombia (Gonzalez-Guzman, 1967); Cenozoic of Brazil (Regali et al., 1974); late Oligocene to Miocene of Santa Cruz Province, Argentina (Barreda and Palamarczuk, 2000a); Tertiary of Colombia and British Guyana (Van der Hammen and Wymstra, 1964).

Order ROSALES Lindley, 1833

Genus RHAMNACEAEPOLLENITES Thielle-Pfeiffer, 1980

Type species. Rhamnaceaepollenites triquetrus Thielle-Pfeiffer, 1980

Rhamnaceaepollenites sp.

Figure 5.22

Material. Sample Pb-9334, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, oblate spheroidal. Tricolporate, endoapertures 5 x 4 µm with margo. Exine semitectate, columellate, 0.8 µm thick, microreticulate to tectate perforate, heterobrochate, brochi less than 1 μm.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 13 µm, polar diameter 13-19 µm, two specimens measured.

Comparisons. Rhamnaceaepollenites sp. has dimensions similar to the type species R. triquetrus (Jansonius and Hills, 1976: 18-20 µm), and presents a faint to distinct reticulate exine (Jansonius and Hills, 1976: card number 3904) which is considered heterobrochate.

Other occurrences. There are no previous records of this taxon in Mexico. This genus has been reported from the Miocene of Turkey (Kayseri and Akgün, 2008).

Family ULMACEAE Mierbel, 1815

Genus ULMIPOLLENITES Wolff, 1934

Type species. Ulmipollenites undulosus Wolff, 1934

Ulmipollenites sp.

Figure 5.18

Material. Samples Pb-9137, Pb-9343, Pb-8896, Pb-8872, Pb-9141, Pb-9138, Pb-8898, Pb-9339, Pb-9340, and Pb-9147, Palynology Laboratory, IGLUNAM.

Description. Monad pollen, isopolar, radiosymmetric, amb subcircular. Tetraporate or pentaporate. Exine tectate, 1 µm thick, suprarugulate.

Dimensions. Equatorial diameter 17-33 µm, five specimens measured.

Comparisons. Considering dimensions and number of pores, Ulmipollenites sp. is similar to U. krempii from the Eocene of California, U.S.A. (Frederiksen et al., 1983) and U. undulosus (Jansonius and Hills, 1976: card number 3121); but the rugulae are less conspicuous in our specimens.

Other occurrences. Mexico - Ulmipollenites has been recovered from the late Eocene to early Oligocene Pie de Vaca Formation (Martíne--Hernández and Ramírez-Arriaga, 1999); Oligocene San Gregorio Formation (Martínez-Hernández and Ramírez, 2006); Oligo-Miocene of Chiapas (Biaggi, 1978); Neogene (Palacios and Rzedowski, 1993); Pliocene, Paraje Solo, Veracruz (Graham, 1975). U.S.A. - late Miocene Valentine Formation, Nebraska (MacGinitie, 1962); late Eocene, Jackson Group, Mississippi and Alabama (Frederiksen, 1980a); Eocene of California (Frederiksen, 1989) and middle Miocene of Florida (Jarzen and Klug, 2010). Initially found in the Tertiary of Germany by Wolff (1934) and Thomson and Plug (1953).

DISCUSSION

The Cuayuca Formation yields rich and diverse palynoflora composed of 97 taxa. Spores are represented by 13.4% (n=13) and gymnosperms 7.2% (n= 7) of the taxa, whereas angiosperms are the most diverse plant group, represented by 76.3% (n= 74) with dominance of Dicotyledonae (66%; n=64) over the Monocotyledonae (10.3%; n=10). Finally, algae are also present with 3.1% (n=3). The present contribution deals with the taxonomy and systematics of selected angiosperm pollen grains (Monocotyledonae and Dicotyledonae) recovered from the Cuayuca Formation (Table). The Monocotyledonae pollen grains are represented by monosulcate and monoporate aperture types; on the other hand, Dicotyledonae pollen grains include colpate, colporate, colporoidate, porate and inaperturate pollen types.

Vegetation types represented in the Cuayuca Formation palynoflora are suggested as a result of comparison between botanical affinities of fossil taxa and the most representative plants reported for current vegetation (Rzedowsky, 2006; Fernández-Nava et al., 1998), as well as comparison between percentages from fossil assemblages against current pollen rain (Velázquez, 2008; Palacios and Rzedowsky, 1993). In general, the palynoflora from the Cuayuca Formation includes taxa belonging to semiarid vegetation such as tropical deciduous forest, chaparral, grassland, and arid tropical scrub, in which angiosperms are one of the main representatives (Table); besides, two temperate vegetation types have been suggested: Pinus forest and cloud forest.

It is important to mention that in the analysis of fossil pollen association, several taphonomic factors must be considered. Since pollen assemblages represent the admixture of a number of plant communities in accordance with their distribution, type of pollen dispersal, biological habit, and proximity to the depositional area, their representativeness will vary greatly in any given space. Despite the previous consideration, hierarchical clustering analysis supports the hypothesis that several plant communities existed at the time of deposition (Figure 6). This analysis was carried out considering the total count of each taxon in order to know whether plant communities were grouped independently. Cluster analysis shows highlighted taxa according to the vegetation type in which they are usually found (Rzedowsky, 2006). In general, three groups are shown in the cladogram. First of all, node A groups four types of vegetation, of which most taxa belong to cloud forest, although elements of tropical deciduous forest, arid tropical scrub, and chaparral are also included. On the other hand, even though most of the taxa included in node B are currently common in tropical deciduous forest (subnodes B-2 and B-3), there are also representatives of cloud forest grouped principally in subnodes B-1 and B2, besides two taxa in B-3. Finally, node C contains Pinus forest and scarce taxa from chaparral, cloud forest, and tropical deciduous forest (Figure 6).

It is important to mention that in the analysis of fossil pollen association, several taphonomic factors must be considered. Since pollen assemblages represent the admixture of a number of plant communities in accordance with their distribution, type of pollen dispersal, biological habit, and proximity to the depositional area, their representativeness will vary greatly in any given space. Despite the previous consideration, hierarchical clustering analysis supports the hypothesis that several plant communities existed at the time of deposition (Figure 6). This analysis was carried out considering the total count of each taxon in order to know whether plant communities were grouped independently. Cluster analysis shows highlighted taxa according to the vegetation type in which they are usually found (Rzedowsky, 2006). In general, three groups are shown in the cladogram. First of all, node A groups four types of vegetation, of which most taxa belong to cloud forest, although elements of tropical deciduous forest, arid tropical scrub, and chaparral are also included. On the other hand, even though most of the taxa included in node B are currently common in tropical deciduous forest (subnodes B-2 and B-3), there are also representatives of cloud forest grouped principally in subnodes B-1 and B2, besides two taxa in B-3. Finally, node C contains Pinus forest and scarce taxa from chaparral, cloud forest, and tropical deciduous forest (Figure 6).

The existence of Pinus forest ( Pinuspollenites: 43.6 - 55.4%) and cloud forest with abundance of Engelhardia - Alfaroa - Oreomunnea ( Momipites: 10.5 - 16.7%) during late Eocene - early Oligocene have also been corroborated by means of comparison between percentages in Cuayuca Formation pollen fossil assemblages and current pollen rain (Velázquez, 2008; Palacios and Rzedowsky, 1993).

The palynoflora is interpreted to have been deposited in a shallow lacustrine environment under semiarid conditions. The local semiarid vegetation surrounding the lake included grassland, arid tropical scrub, and tropical deciduous forests. Upland plant communities are represented by Pinus forest and cloud forest (Ramírez-Arriaga et al., 2006, 2008).

PAE Analysis between Cuayuca Formation Sections

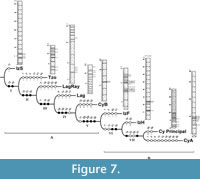

PAE analysis included the presence/absence of 44 palynomorphs (Appendix 3) and resulted in one cladogram in which L= 89, CI = 0.50 and RI = 0.54 (Figure 7). Upon analysis, the cladogram shows that the base of the tree -node I- groups Tzompahuacan (Tzo) with all other clades due to the presence of Liliacidites (13) and Tubulifloridites (42). Level II clusters Lagunillas de Rayón (LagRay) with node III sections based on the presence of Alnus vera (15), Quercoidites (31) and Rhoipites aff. cryptoporus (32).

PAE analysis included the presence/absence of 44 palynomorphs (Appendix 3) and resulted in one cladogram in which L= 89, CI = 0.50 and RI = 0.54 (Figure 7). Upon analysis, the cladogram shows that the base of the tree -node I- groups Tzompahuacan (Tzo) with all other clades due to the presence of Liliacidites (13) and Tubulifloridites (42). Level II clusters Lagunillas de Rayón (LagRay) with node III sections based on the presence of Alnus vera (15), Quercoidites (31) and Rhoipites aff. cryptoporus (32).

Cupressacites/Taxodiaceaepollenites (7), Monoporopollenites (12) and Chenopodipollis (20) provide support for node III to group Lagunillas (Lag) with node IV. Clade IV relates the Cuayuca “B” section with node V because they share Momipites microcoryphaeus (25), Myrtaceidites (28) and Ulmipollenites (43). Node V associates the Cuayuca B section with node VI based on the presence of Momipites tenuipolus (26), Platanoidites (29), Rugulitriporites (33) and Armeria type (38). Izúcar de Matamoros “F” section and node VII share Eucommia (21) and Striatricolporites (35). Finally, the derived state -node VII- shows cladistic relationship between the Cuayuca Principal section and Cuayuca Section A (CyA) due to the presence of Aglaoreidia (10) and Aeschynomene (37).

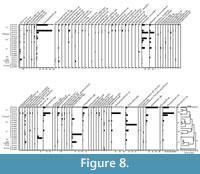

PAE analysis applied to Cuayuca sections expresses historical links, related by space-time (Figure 7). According to field observations, sections grouped at the base of the cladogram correspond to the base of the Cuayuca Mcy Member (Figure 7: group A); in contrast, the most derived sections shown in the cladogram are located within the upper layers (Figure 7: group B) of the Cuayuca Formation. On the other hand, basal sections were less diverse, while more derived sections are the most diverse and yield a great abundance of palynomorphs (Figure 8).

PAE analysis applied to Cuayuca sections expresses historical links, related by space-time (Figure 7). According to field observations, sections grouped at the base of the cladogram correspond to the base of the Cuayuca Mcy Member (Figure 7: group A); in contrast, the most derived sections shown in the cladogram are located within the upper layers (Figure 7: group B) of the Cuayuca Formation. On the other hand, basal sections were less diverse, while more derived sections are the most diverse and yield a great abundance of palynomorphs (Figure 8).

Finally, index taxa such as Aglaoreidia (10), Eucommia (21), Momipites tenuipolus (26), and Armeria (38) are found among the taxa defining the most derived hierarchic levels. On the other hand, two index taxa are located at different hierarchic levels: Ranunculacidites operculatus (30) and Thomsonipollissabinetownensis (36).

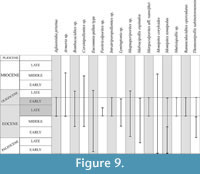

CONISS Analysis