In a museum filled with towering dinosaurs, six small trilobites tell a big story. Paleontologists Russell Bicknell and Brayden Holland from University of New England, NSW documented evidence of injuries on trilobite fossils at the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in Alberta, Canada, providing clues about predator-prey relationships in the Cambrian Period.

Trilobites were one of the oldest groups of arthropods—animals with exoskeletons and joint-legs, that includes insects and crustaceans. “A trilobite kind of looks like a slater (an isopod),” said Dr. Bicknell, “but has an exoskeleton that is made out of calcium carbonate, literal rock! And often they have a lot more spines than modern day isopods.”

This hard exoskeleton allowed trilobites to be easily preserved in the fossil record, and as one of the most diverse and successful arthropods in history, trilobites fill the Paleozoic fossil record. These creatures have been incredibly useful to paleontologists, from uncovering aspects of evolution to supporting continental drift. But they have also been ideal for studying predator-prey relationships. When a predator attacks a trilobite, and the trilobite manages to escape, the exoskeleton is left with injuries that carry over to fossils.

The researchers identified six abnormal trilobites from over 5000 specimens at the Tyrrell Museum, which is best known for its collection of dinosaurs but also hosts many invertebrate fossils.

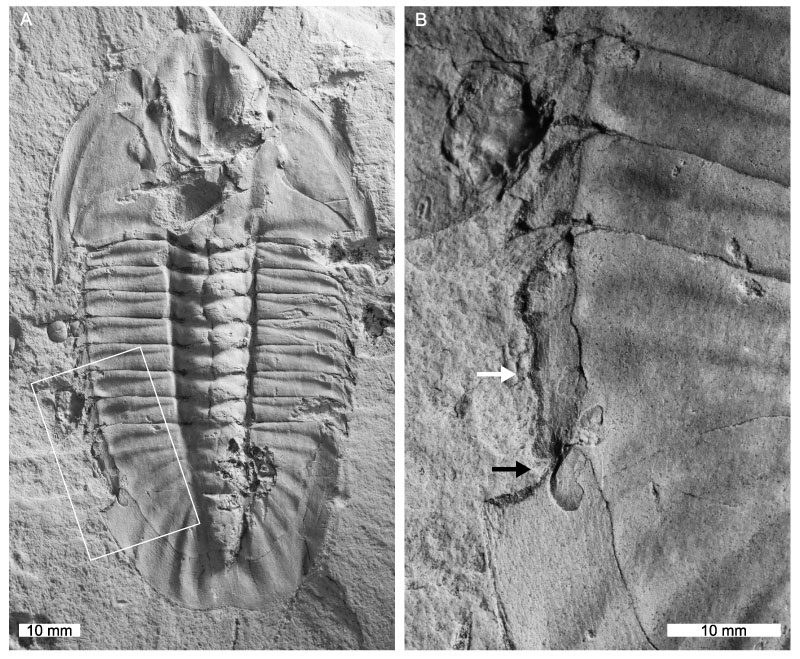

A V-shaped (black arrow) and W-shaped (white arrow) indentation on a trilobite fossil from the Tyrell museum collection. [Figure 4 in original article]“We look for specimens that have missing spines, indentations along the edge of the specimen, and any indication of callousing where there are parts missing,” said Dr. Bicknell. The most common evidence of predator attack is a “V” or “W”-shaped indentation in different parts of the exoskeleton.

A V-shaped (black arrow) and W-shaped (white arrow) indentation on a trilobite fossil from the Tyrell museum collection. [Figure 4 in original article]“We look for specimens that have missing spines, indentations along the edge of the specimen, and any indication of callousing where there are parts missing,” said Dr. Bicknell. The most common evidence of predator attack is a “V” or “W”-shaped indentation in different parts of the exoskeleton.

This evidence of injuries raises the question, who were the trilobites’ predators?

“Well this is an interesting question. Presently, we think that animals that had gnathobases on their legs, like horseshoe crabs, were likely the key injury makers,” said Dr. Bicknell.

Gnathobases are small spines on the upper legs used for breaking up hard-shelled critters, allowing predators to “bite” with their legs.

“Trilobites have these structures, so it is likely that trilobites may have been cannibals,” said Dr. Bicknell.

The researchers documented a variety of injuries and their likely causes, including the first evidence of injury on the trilobite species Hemirhodon amplipyge. They published their findings in Palaeontologia Electronica in July 2020.

While the Tyrrell collection primarily focuses on dinosaurs, this research highlights the value of searching through under-studied museum collections for hidden gems.

“[Museums] are perfect for conducting a 'Cook's Tour,' so to speak, of material— without needing to go out to sometimes some very isolated field localities,” said Dr. Bicknell. “They also give us an idea of where we might want to return to gather more material, if there is an abundance of abnormal specimens.”

To read more about this study, you can find the original article here.

Kerste Milik

Kerste Milik