Hannah Bird

Whilst indulging in a summer picnic or barbeque we may consider flies bothersome, but have you ever contemplated their evolution? Incredibly, many of their genera have astonishing longevity, establishing themselves in the Middle Triassic (247 to 237 million years ago) and with some living species existing for millions of years. There are 161 families of flies today, living in almost all environments on Earth. Perhaps it’s time to regard them a little more kindly and that is exactly what researchers from the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and their collaborators, have done for the last decade.

The Kishenehn Formation in northwestern Montana, USA, originates from the middle Eocene (45.8 to 46.6 million years ago) and is a site of exceptional preservation, known as a Lagerstätte. Tiny insects (Diptera) less than 1mm in length are preserved in mesmerising detail, including their wings, antennae, and even their colouration.

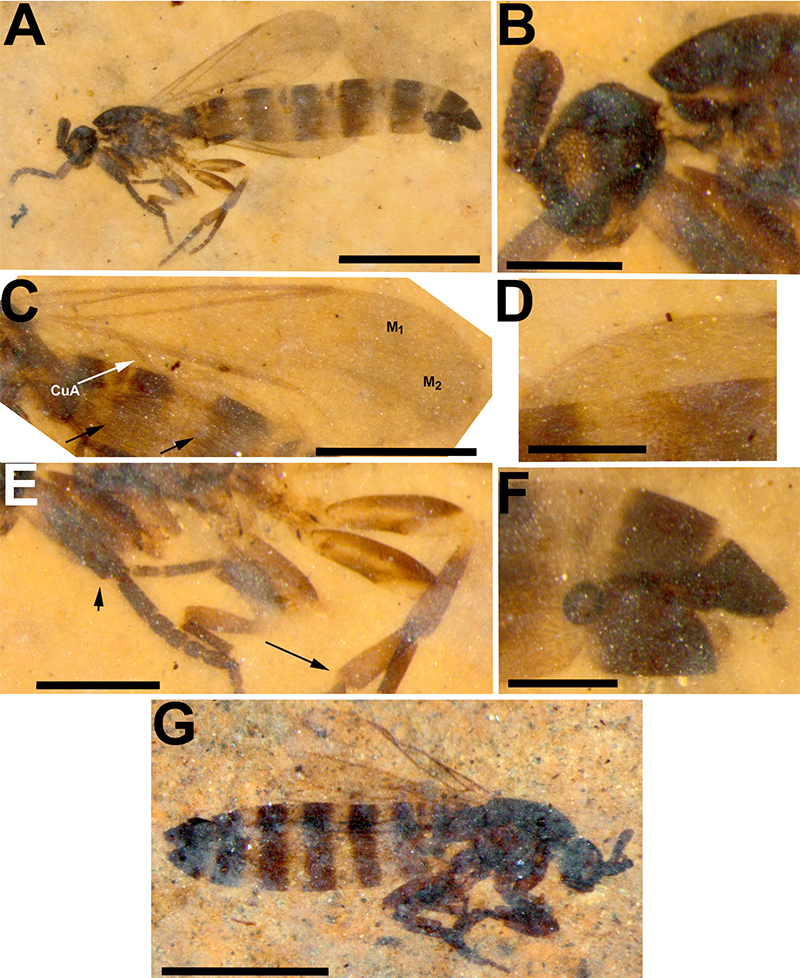

A – F. A female Psectrosciara makrochaites Amorim and Greenwalt sp. n. (USNM 625934). Detailed images reveal the head and antennae structure (B), wing veins (C), tiny hairs (microsetae) on the wing surface (D), legs (E), and genitalia (F). G. A female Psectrosciara crassieton Amorim and Greenwalt sp. n. (USNM 625035). Scale bars equal 1.0 mm (A, G), 0.5 mm (B), 0.3 mm (C) and 0.2 mm (D – F).Lead researcher Dr Dale Greenwalt reveals how these amazing specimens came to be preserved: “Our research has led us to believe that tiny flying insects were caught on the sticky surface of a green mat of algae on the surface of an ancient lake. The algae proliferated and surrounded, entombed and protected the insects. When the algal mat died and sank to the lake’s bottom, it retained the insects intact; subsequent burial in sediment, and a great deal of time, led to the production of fossiliferous shale. The exceptional preservation at the Kishenehn locality has resulted in fossils of tiny fragile insects that have not been found at other fossil localities; for example, it is one of the best places in the world to find fossil mosquitos. Most amazing is the presence of nine specimens of fossil blood-engorged mosquitos - the only such specimens known to science.”

A – F. A female Psectrosciara makrochaites Amorim and Greenwalt sp. n. (USNM 625934). Detailed images reveal the head and antennae structure (B), wing veins (C), tiny hairs (microsetae) on the wing surface (D), legs (E), and genitalia (F). G. A female Psectrosciara crassieton Amorim and Greenwalt sp. n. (USNM 625035). Scale bars equal 1.0 mm (A, G), 0.5 mm (B), 0.3 mm (C) and 0.2 mm (D – F).Lead researcher Dr Dale Greenwalt reveals how these amazing specimens came to be preserved: “Our research has led us to believe that tiny flying insects were caught on the sticky surface of a green mat of algae on the surface of an ancient lake. The algae proliferated and surrounded, entombed and protected the insects. When the algal mat died and sank to the lake’s bottom, it retained the insects intact; subsequent burial in sediment, and a great deal of time, led to the production of fossiliferous shale. The exceptional preservation at the Kishenehn locality has resulted in fossils of tiny fragile insects that have not been found at other fossil localities; for example, it is one of the best places in the world to find fossil mosquitos. Most amazing is the presence of nine specimens of fossil blood-engorged mosquitos - the only such specimens known to science.”

The process of finding such shale in the field to photographing the beautiful specimens requires splitting the shale along points of weakness (fortunately coinciding with the algal mat layers) but the specimens are so small they cannot be seen with the naked eye. The shale must be moistened and inspected with a magnifying lens to identify fossil-bearing pieces before scientists can determine which families they belong to and photograph them using a microscope. The process is time-consuming, with several months’ work required to process the samples (approximately a thousand insects each summer). Considerably more time is then required to identify them all to a particular species or genus.

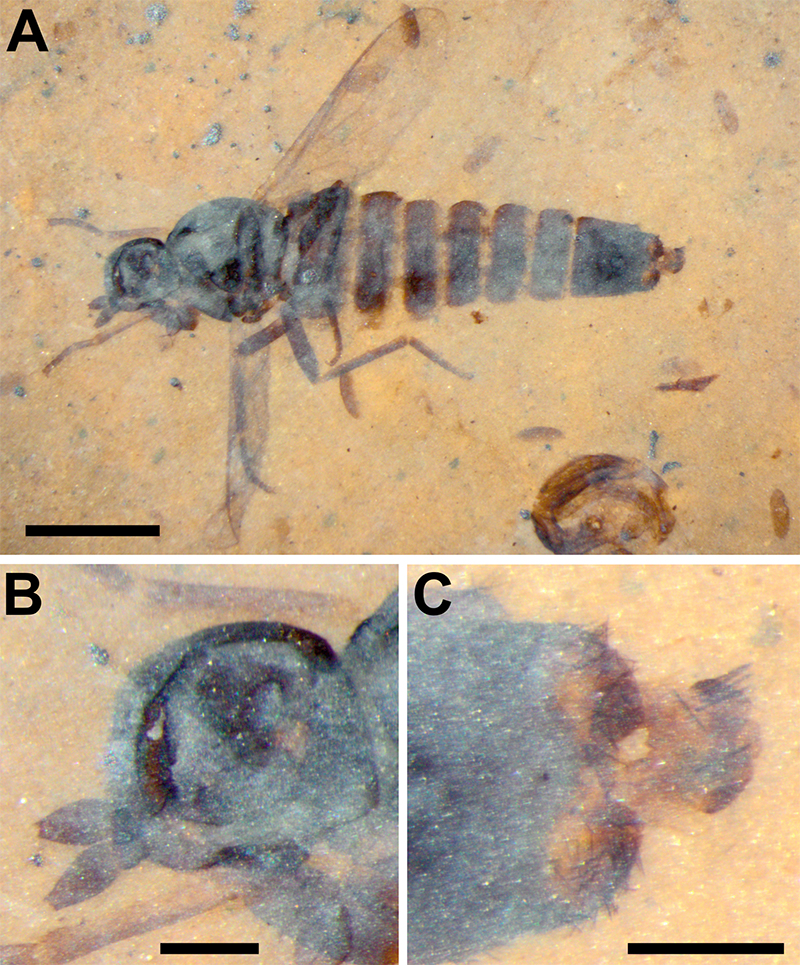

But the tenacity of the scientists has been worth it. The Kishenehn Formation has yielded 25 families and 38 fossil species, with many instances of the first fossil of a particualr genus being found, as well as the oldest definitive representitive of the Scenopinidae family (window flies), Brevitrichia messogenes.

A - C. A female Brevitrichia messogenes Greenwalt and Winterton sp. n. (USNM 620163). Detailed images show the head and antennae (B) and genitalia (C). Scale bars equal 1.0 mm (A) and 0.2 mm (B, C).

A - C. A female Brevitrichia messogenes Greenwalt and Winterton sp. n. (USNM 620163). Detailed images show the head and antennae (B) and genitalia (C). Scale bars equal 1.0 mm (A) and 0.2 mm (B, C).

Studying such insects is an important window into the diversity of life during the middle Eocene, a period of global warming, with Dr Greenwalt explaining how scientists can track changes in climatic conditions through these ancient organisms.

“The fossil evidence tells us that many of the flies from the Kishenehn locality had life cycles that included aquatic larvae (such as mosquitos). However, some of the fossil insects at the Kishenehn locality are related to modern insects that inhabit forests, an indication that the ancient lake(s) were surrounded by forests, a conclusion that is supported by other evidence. Modern flies that belong to the genus Tmemophlebia live on sandy dunes, so the descendants of 46-million-year-old Tmemophlebia carolinae appear to have transitioned through the desertification process that occurred in the western United States tens of millions of years after the Kishenehn shales were formed.”

This is a spectacular visual and theoretical insight into the diversity of insects living in and around a lake in semitropical Montana tens of millions of years ago, in an environment we may consider similar to present-day Florida.

To discover more about this research, read the full publication here.