The study of fossil macroinvertebrates from the Santana Group, Brazil: Legal and ethical challenges and neocolonial legacies in paleontology

The study of fossil macroinvertebrates from the Santana Group, Brazil: Legal and ethical challenges and neocolonial legacies in paleontology

Article number: 28.3.a51

https://doi.org/10.26879/1563

Copyright Paleontological Society, November 2025

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Appendices

Submission: 13 April 2025. Acceptance: 21 October 2025.

ABSTRACT

Fossil invertebrates from the Araripe Basin, located in Northeast Brazil, have long been the focus of extensive scientific research. The region’s precarious socioeconomic conditions, nonetheless, are frequently exploited by individuals involved in the illicit extraction and trafficking of fossils, resulting in their transfer abroad and subsequent deposition in foreign collections. Such specimens are often studied and described with minimal or no collaboration with scientists from their region of origin, a practice commonly characterized as “parachute science” - one of the many manifestations of “scientific colonialism”. This study presents a comprehensive literature review of publications concerning fossil invertebrates from the Santana Group (Araripe Basin). We compiled an updated inventory detailing the known repositories of these species, aiming to assess the extent to which they have been subject to such practices. Our findings reveal nearly five hundred described species, with approximately half of the holotypes deposited in institutions across Europe, Asia, and North America. Furthermore, over two hundred species were described in publications that did not include any Brazilian scientists as co-authors. We also examine the potential mechanisms by which these specimens may have been removed from the country and propose strategies to prevent and mitigate the ongoing loss of Brazil’s cultural and scientific heritage.

Matheus A. Macário. Paleontology and Paleoecology Laboratory, Department of Geology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. (Corresponding author) macario.cma@gmail.com

Aline M. Ghilardi. Paleontology and Paleoecology Laboratory, Department of Geology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. aline.ghilardi@ufrn.br

Elis M. G. Santana. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Diversidade Biológica e Recursos Naturais (PPGDR), Department of Biological Sciences, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, CE, Brazil. eg00063@mix.wvu.edu

Ednalva S. Santos. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Diversidade Biológica e Recursos Naturais (PPGDR), Department of Biological Sciences, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, CE, Brazil; Secretaria de Educação e Transportes, Araripina, PE, Brazil. ednalva.santos@urca.br

Anamaria Dal Molin. Entomological Collection, Department of Microbiology and Parasitology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. anamaria.dal.molin@ufrn.br

Letícia M. Haertel. Paleontology Museum Plácido Cidade Nuvens, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Santana do Cariri, CE, Brazil. lehaertel@gmail.com

Tito Aureliano. Paleontology and Paleoecology Laboratory, Department of Geology, Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Norte, Natal, RN, Brazil. Department of Biological Sciences, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, CE, Brazil. aureliano.tito@gmail.com

Allysson P. Pinheiro. Department of Biological Sciences, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, CE, Brazil. Paleontology Museum Plácido Cidade Nuvens, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Santana do Cariri, CE, Brazil. allysson.pinheiro@urca.br

Daniel Lima. Paleontology Museum Plácido Cidade Nuvens, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Santana do Cariri, CE, Brazil. danieljmlima@gmail.com

Antony Thierry de O. Salú. Araripe UNESCO Global Geopark, Crato, CE, Brazil. thierry.salu@urca.br

Juan C. Cisneros. Museu de Arqueologia e Paleontologia, Universidade Federal do Piauí, Teresina, PI, Brazil. juan.cisneros@ufpi.edu.br

Antônio Álamo Feitosa Saraiva. Laboratório de Paleontologia da URCA (LPU), Department of Biological Sciences, Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, CE, Brazil. alamocariri@yahoo.com.br

Keywords: scientific colonialism; taxonomic survey; paleontological heritage; data sovereignty; epistemic colonialism

Final citation: Macário, Matheus A., Ghilardi, Aline M., Santana, Elis M. G., Santos, Ednalva S., Molin, Anamaria Dal, Haertel, Letícia M., Aureliano, Tito, Pinheiro, Allysson P., Lima, Daniel, de O. Salú, Antony Thierry, Cisneros, Juan C., and Saraiva, Antônio Álamo Feitosa. 2025. The study of fossil macroinvertebrates from the Santana Group, Brazil: Legal and ethical challenges and neocolonial legacies in paleontology. Palaeontologia Electronica, 28(3):a51.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1563

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2025/5703-macroinvertebrates-from-the-santana-group

Copyright: November 2025 Paleontological Society

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits users to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided it is not used for commercial purposes and the original author and source are credited, with indications if any changes are made.

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

INTRODUCTION

The Araripe Basin, located in Northeast Brazil, is internationally recognized for its extensive fossil record, particularly from the Crato and Romualdo formations of the Santana Group (Lower Cretaceous). However, this paleontological abundance stands in stark contrast to the region’s socioeconomic challenges, marked by high poverty rates and significant income disparities (AtlasBR, 2022; IBGE, 2010). These conditions have historically facilitated the illicit trade of fossils (Farrar, 1999; Vilas-Boas et al., 2013). Over time, fossil extraction has become a source of supplementary income for some members of the local community, who, by engaging in such activities, may inadvertently expose themselves to legal risks.

Brazilian legislation has classified fossils as State property since 1942, prohibiting their commercialization and subjecting their extraction to prior authorization and oversight. Despite this and subsequent increasingly protective legal measures, Brazilian fossils continue to be illegally extracted, sold, and exported–frequently ending up in foreign institutions (Gibney, 2014). These specimens are often studied without the involvement of Brazilian researchers or institutions (Cisneros et al., 2022b), exemplifying a form of ‘parachute science’ that reproduces colonial dynamics in contemporary research (Odeny and Bosurgi, 2022, Minasny et al., 2020; Raja et al., 2022).

This practice has far-reaching consequences. Beyond violating national laws, the study of irregularly acquired fossils often undermines scientific rigor, as these specimens typically lack essential contextual data such as precise stratigraphic and geographic provenance (Cisneros et al., 2022b; Raja and Dunne, 2023). In some instances, fossils are deliberately altered to enhance their market value, as in the case of the dinosaur Irritator challengeri Martill et al., 1996 (Scheyer et al., 2023, Schade et al., 2023). Moreover, disputes over ownership and provenance have led to escalating legal and ethical tensions, eroding trust between local and foreign researchers. The publication of the “four-legged snake” Tetrapodophis amplectus Martill et al, 2015 (specimen BMMS BK 2-2), for example, triggered immediate controversy when Brazilian scientists questioned the fossil’s legal status and its deposition in a private foreign collection (Martill et al., 2015; Carvalho, 2015). The more recent case of the dinosaur “Ubirajara jubatus” (Caetano et al., 2023) extended beyond academic circles, sparking widespread public outcry (Cisneros et al., 2022a; Kashani et al., 2024).

While vertebrate fossils have often taken center stage in discussions of fossil repatriation and scientific colonialism, macroinvertebrates–particularly arthropods from the Crato Formation–are similarly subject to these dynamics. Invertebrate fossils comprise the majority of species described from the Araripe Basin, yet they have received relatively little attention in legal and ethical debates.

In this study, we present an updated inventory of macroinvertebrate fossils described from the Araripe Basin, detailing current repository data, authorship patterns, and whether publications report collection or export permits. Through this, we assess the extent to which these fossils have been subject to colonial scientific practices and examine their broader implications for heritage governance and research equity. Our findings offer new insights into the ongoing impact of the illegal fossil trade in the Araripe region. By addressing these issues, this study contributes to debates on fossil repatriation, ethical research practices, and the responsibilities of scientists working with paleontological heritage from historically exploited regions.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

To compile the complete historical record of fossil macroinvertebrate species from the Araripe Basin, covering the period from 1955 to 2025, we conducted systematic searches using the Periódicos CAPES search engine (http://periodicos.capes.gov.br). This metasearch platform aggregates data from most research databases, including EBSCO, OVID, CABI, BioOne, Clarivate’s Zoological Record, SCOPUS, and others. The search was conducted using CAFe (Federated Academic Community) access, which enables full-text retrieval from journals and publishers under contract with Brazilian federal universities. Our search queries included the following combinations: “Araripe+Basin”, “Crato+Formation'' or “Santana+Formation”, along with names of the main invertebrate groups (e.g., Mollusca, Crustacea, Arachnida, Myriapoda, Ephemeroptera, Neuroptera, etc.). Microarthropods such as Spinicaudata and Ostracoda, which are commonly used in stratigraphy, were not included (see Appendix 1 for a complete list of search terms).

Additionally, we reviewed prior syntheses on Brazilian fossil arthropods (Martins-Neto, 2005a; Martill et al., 2007; Moura-Júnior et al., 2018), as well as a review of fossil Neuropterida from Brazil, given the high species diversity within this superorder (Martins et al., 2023).

To assess potential ethical and legal issues and indicators of neocolonialist practices, we examined Brazilian legislation in effect at the time of collection and publication. We then analyzed factors commonly linked to colonial scientific practices (Galtung, 1967; Nicholas and Hollowell, 2007; Seth, 2009; Hira, 2015; Raja et al., 2022), particularly those identified by Cisneros et al. (2022b). We assessed: (1) whether holotypes were deposited in foreign institutions or private collections; (2) whether holotypes were deposited in Brazilian institutions, particularly in the Araripe region; (3) the composition of authorship, with a focus on the presence or absence of Brazilian researchers; (4) whether the publication included information on collection and/or export permits; and (5) whether the fossil has been repatriated to Brazil.

For this analysis, "foreign researchers" were defined as those affiliated with non-Brazilian institutions, whereas "Brazilian researchers" were defined as those affiliated with Brazilian institutions, regardless of nationality. This criterion was adopted because institutional affiliation, rather than nationality, more accurately reflects access to local infrastructure, funding opportunities, curatorial responsibilities, and legal accountability regarding fossil collection and research.

We acknowledge that some Brazilian nationals have developed academic careers abroad and may co-author or lead studies involving fossil specimens from Brazil. While such cases might appear as exceptions to the affiliation-based model, we argue that they are themselves symptomatic of the broader colonial legacy this study seeks to examine. The structural asymmetries that encourage or compel Brazilian scientists to work in foreign institutions–often due to unequal access to resources, visibility, and international prestige–highlight the persistence of neocolonial dynamics within global scientific systems. For this reason, we chose to use institutional affiliation as our primary analytical criterion, as it better captures the systemic conditions under which access, authorship, and scientific benefit are distributed.

To complement our analysis, we also evaluated the accessibility of surveyed publications to Brazilian researchers by determining how many were available through open-access on the journal’s platform or via Periódicos CAPES subscriptions accessed through the CAFe (Federated Academic Community). By considering both the physical location of holotypes and the accessibility of publications, we sought to identify structural barriers that may prevent local researchers from accessing not only the fossils themselves but also the relevant literature necessary for research, dissemination, and conservation efforts.

Finally, to investigate the illegal trade of Brazilian fossil macroinvertebrates, we conducted a targeted online search on Google for newspaper articles reporting fossil trafficking cases, legal actions against fossil smugglers, and historical interviews conducted with Brazilian paleontologists. We used the following keywords: "Araripe+Tráfico+fósseis," "Tráfico+fósseis+Ceará".

Institutional Abbreviations

AMNH, American Museum of Natural History, New York, USA; CPCA, Centro de Pesquisas Paleontológicas da Chapada do Araripe, Crato, Brazil; CV-MZUSP, Private Collection of Dra Maria Aparecida Vulcano (Currently at MZUSP), São Paulo, Brazil; DNPM (ANM), Agência Nacional de Mineração (former Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral), Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; IGc-USP (IGeo USP), Instituto de Geociências, Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; KMNH, Kitakyushu Museum and Institute of Natural History, Kitakyushu, Japan; KUMIP, Kansas University Museum of Invertebrate Paleontology, Lawrence, USA; LPU-URCA, Laboratório de Paleontologia da Universidade Regional do Cariri, Crato, Ceará, Brazil; MCNHBJ, Museu de Ciências Naturais e História de Bom Jardim, Jardim, Brazil; MCTI, Ministério da Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação, Brasília, Brazil; MfN-B, Museum für Naturkunde, Berlin, Germany; NHMUK, Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom; MNHN, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, France; MN-UFRJ, National Museum - Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; MPPCN, Museu de Paleontologia - Plácido Cidade Nuvens, Santana do Cariri, Ceará, Brazil; MZUSP, Museu de Zoologia da Universidade de São Paulo, São Paulo, Brazil; PC-MN, Private Collection of Dr Rafael Gioia Martins-Neto; PC-MS, Private Collection of Mr. Markus Sennlaub; SMNK, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Karlsruhe, Germany; SMNS, Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Stuttgart, Germany; UFABC, Universidade Federal do ABC, São Bernardo do Campo, São Paulo, Brazil; UFCA, Universidade Federal do Cariri, Ceará, Brazil; UFPE, Universidade Federal de Pernambuco, Recife, Brazil; UNESP, Universidade Estadual Paulista, Rio Claro, São Paulo, Brazil; UnG, Laboratório de Geociências da Universidade Guarulhos, Guarulhos, São Paulo, Brazil; WDC, Wyoming Dinosaur Center, East Thermopolis, Wyoming, EUA.

RESULTS

Our survey identified 491 fossil macroinvertebrate species described from the Santana Group, with 490 holotypes (see below), documented across 218 publications, including peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. Nearly half of all analyzed publications (104 out of 218; 47.7%) were authored exclusively by foreign researchers, with no Brazilian co-authors. The complete species list and references are provided in the Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

Our survey identified 491 fossil macroinvertebrate species described from the Santana Group, with 490 holotypes (see below), documented across 218 publications, including peer-reviewed articles and book chapters. Nearly half of all analyzed publications (104 out of 218; 47.7%) were authored exclusively by foreign researchers, with no Brazilian co-authors. The complete species list and references are provided in the Appendix 2 and Appendix 3.

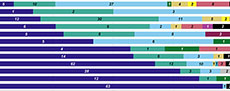

The earliest published description of a macroinvertebrate fossil from the Araripe Basin dates to 1955 (Demoulin, 1955), although no holotype was designated. Four additional species were described in 1964 and 1966 (Beurlen, 1964, 1966), followed by a publication gap until 1986. Since then, new species have been described nearly every year, except for 1993, with notable peaks in 1990 (72 species) and 2007 (37 species) (Figure 1).

Among all recorded species, hexapods account for the vast majority (452 species; 92.2%), followed by crustaceans (14 species; 2.9%), arachnids (12 species; 2.5%), mollusks (7 species; 1.5%), millipedes (3 species; 0.6%), and echinoderms (2 species; 0.4%).

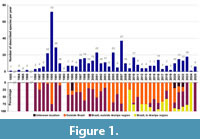

Nearly half of the surveyed holotypes (225 out of 490; 45.9%) are deposited in foreign collections, mainly in Germany (91; 40.4%) and the United States (84; 37.3%). Others are housed in France (15; 6.7%), Japan (12; 5.3%), Italy (5; 2.2%), the United Kingdom (4; 1.8%), Poland (2; 0.9%), Canada (1; 0.4%), and Spain (1; 0.4%). Only 11 species (4.9%) with holotypes abroad were described with the participation of Brazilian co-authors.

Nearly half of the surveyed holotypes (225 out of 490; 45.9%) are deposited in foreign collections, mainly in Germany (91; 40.4%) and the United States (84; 37.3%). Others are housed in France (15; 6.7%), Japan (12; 5.3%), Italy (5; 2.2%), the United Kingdom (4; 1.8%), Poland (2; 0.9%), Canada (1; 0.4%), and Spain (1; 0.4%). Only 11 species (4.9%) with holotypes abroad were described with the participation of Brazilian co-authors.

The foreign institutions that house the largest number of holotypes are the AMNH (USA, 71) and the SMNS (Germany, 66), followed by MNHN (France, 11), the WDC (USA, 8), the SMNK (Germany, 7), and the KMNH (Japan, 6) (Figure 2).

Among all surveyed fossil species, only 24 (5.0%) were described with holotypes deposited in institutions located within the Araripe region (MPPCN, LPU-URCA, UFPI-Picos, MCNHBJ, CPCA, and UFCA). Most holotypes preserved in Brazilian institutions are concentrated in the states of São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro (148; 55.8%), both located in the Southeast region. In São Paulo, the MZUSP holds 51 holotypes, including specimens formerly housed in the Vulcano Private Collection (see below), while the IGc-USP holds 28, and UnG, 23.

None of the analyzed publications describing holotypes held abroad included any reference to extraction or export permits. However, a few explicitly mentioned the purchase of fossil material. For example, Bechly (1998a) stated that the described fossil was acquired for US$800.00.

Of the 225 holotypes housed abroad, 18 are located in private foreign collections. Of these specimens, 10 are distributed between France (1), Spain (1), Germany (2), Italy (2), and Japan (4). For the remaining eight holotypes, the original publications did not specify the location of the private collections where the specimens were held.

In Brazil, 44 holotypes were originally described based on material from the so-called "Vulcano Collection", a private collection curated by Dr. Maria Aparecida Vulcano in São Paulo. This collection was formally transferred to MZUSP in 2018 (Durte and Silveira, 2023). Including both the Vulcano and Martins-Neto collections, a total of 108 species were described based on material from private collections in Brazil.

Of the 218 publications analyzed, 107 (49.1%) were not available online through journal websites or through access provided by the Periódicos CAPES system via the Federated Academic Community (CAFe). Additionally, 26 papers (12.1%) were not available in digital format at all, requiring searches for physical copies of journals or reliance on secondary sources such as reviews and species lists.

The results for each major group of fossil macroinvertebrates analyzed are presented in the subsections below.

Hexapoda

The first mention of fossil insects from the Araripe Basin was the report of ephemeropteran naiads by Costa-Lima (1950). These specimens were later described asProtoligoneuria limai Demoulin, 1955, although no holotype was designated, and no information was provided regarding the material repository. Research on Araripe fossil insects stalled until several species were described in the late 1980s (Pinto and Purper, 1986; Martins-Neto and Vulcano, 1988; Brandão et al., 1989), which reignited and accelerated studies in the region. Since then, new species of fossil insects from Araripe have been described almost every year.

Between the 1980s and 2000s, four major reviews of Brazilian Cretaceous paleoentomofauna were conducted (Martins-Neto, 1987a, 1999, 2005a; Petrulevicius and Martins-Neto, 2000). The most recent review, published in 2018 (Moura-Júnior et al., 2018), listed 379 fossil insects from the Araripe Basin. Since then, the number of described species has increased, totaling 452 fossil hexapod species.

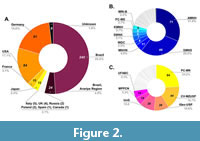

The repository locations of holotypes are unevenly distributed (Figure 3). The majority of surveyed holotypes (238; 52.7%) are held in Brazilian collections, followed by the USA (83; 18.4%) and Germany (82; 18.1%). Other countries with holotype material include France (15; 3.3%), Japan (12; 2.7%), Italy (5; 1.1%), Russia (2; 0.4%), Poland (2; 0.4%), the United Kingdom (2; 0.4%), Canada (1; 0.2%), and Spain (1; 0.2%).

The repository locations of holotypes are unevenly distributed (Figure 3). The majority of surveyed holotypes (238; 52.7%) are held in Brazilian collections, followed by the USA (83; 18.4%) and Germany (82; 18.1%). Other countries with holotype material include France (15; 3.3%), Japan (12; 2.7%), Italy (5; 1.1%), Russia (2; 0.4%), Poland (2; 0.4%), the United Kingdom (2; 0.4%), Canada (1; 0.2%), and Spain (1; 0.2%).

All holotypes of Trichoptera, Lepidoptera, Phasmatodea, and Mecoptera are deposited in Brazilian collections (see Appendix 2). Orthoptera has 95.5% of its holotypes in Brazil, while Diptera (77.8%), Neuroptera (67.4%), Blattaria (65.8%), and Ephemeroptera (58.3%) also have a majority of their holotypes within Brazilian institutions. In contrast, Odonata (91.4%), Dermaptera (83.3%), Hemiptera (80.3%), and Coleoptera (70.6%) have a higher number of holotypes abroad. All the holotypes of Mantodea, Megaloptera, and Coxoplectoptera - a proposed sister group to Ephemeroptera (Godunko et al., 2011), are located in foreign collections.

In addition to insects, an Entognathan hexapod, the dipluran Ferrojapyx vivax Wilson and Martill, 2001, has its holotype housed in Germany (SMNS). Of the 452 described species, only 15 (3.3%) were based on material deposited in institutions in the Araripe region, representing less than 7% of all hexapod holotypes in Brazil.

Nearly all Araripe fossil hexapods, except for one species (the Araripegryllus romualdoi Freitas et al., 2016), originate from the Crato Formation. Almost half of these specimens (206; 45.6%) were described without collaboration from Brazilian authors.

Crustacea

Unlike the insects, which are primarily from the Crato Formation, crustaceans are mostly found in the Romualdo Formation, although several specimens have also been recovered from the Ipubi Formation (Martins-Neto 2005a; Barros et al. 2020). The first macrocrustacean described for the Araripe Basin was the crab Araripecarcinus ferreirae Martins-Neto, 1987, from the Romualdo Formation. Since then, 14 additional species have been described, belonging to taxa including Brachyura, Dendrobranchiata, Caridea, Copepoda, and Stenopodidea.

Most holotypes (12; 85.7%) are in Brazilian collections, and the majority (9; 64.3%) are located within institutions in the Araripe region. The holotype of Kabatarina pattersoni Cressey and Boxshall, 1989, is in the United Kingdom (NHMUK), and another, Paleomattea deliciosa Maysey and Carvalho, 1995, is in the United States (AMNH).

Myriapoda

Myriapods from the Araripe Basin are represented by three described species from the Crato Formation:Velocipede bettimari Martill and Barker, 1998,Fulmenocursor tenax Wilson, 2001, and Cratoraricus oberlii Wilson, 2003. Additionally, a species tentatively assigned to the genus Rhysida Wood, 1982 (Martill et al., 2007) has been recorded. All specimens are currently in German museums (SMNK and SMNS).

Arachnida

A total of 12 fossil arachnid species have been recorded from the Araripe Basin, including representatives of Araneae, Acari, Scorpiones, Thelyphonida, and Amblypygi. All these species originate exclusively from the Crato Formation. The earliest described species in this group was the scorpion Araripescorpius ligabuei Campos, 1986. Half of the holotypes (6; 50%) are in German collections, while nearly half (5; 41.6%) are deposited in Brazil, and the remainder (1; 8.3%) is located in Northern Ireland.

A significant recent event in the context of Araripe fossil arthropods was the repatriation of the holotype of the palpimanid spider Cretapalpus vittari Downen and Selden, 2021 (see Advancements and Challenges section).

Marine Invertebrates

Marine invertebrates from the Araripe Basin are found exclusively in the Romualdo Formation and include two species of Echinodermata and seven species of Mollusca. Unlike the arthropods, all holotypes of these marine species are deposited in Brazilian collections, specifically at UFPE.

The known echinoderm species were described in 1966 by German paleontologist Karl Beurlen, at the time a professor in the Geology Department of UFPE, Recife, Brazil. Similarly, the seven known species of mollusks from the Araripe Basin are kept in the same collection. The first two fossil species of mollusks from Araripe were described by Karl Beurlen in 1964, and the others were published more recently, also by UFPE researchers, between 2015 and 2016 (Pereira et al., 2015, 2016).

DISCUSSION

In the following discussion, we first provide an overview of the Brazilian legislation concerning fossil heritage, contextualizing the legal framework that governs the collection, commercialization, and export of paleontological specimens. We then analyze the legal and ethical issues revealed by our study, with particular emphasis on the distribution and authorship of holotypes, and the implications these patterns hold for understanding scientific colonialism in macroinvertebrate fossil research from the Araripe Basin. Subsequently, we explore how a focus solely on holotypes fails to capture the full extent of extractive research practices, considering also the challenges posed by private collections and the role of undocumented specimens. Finally, we examine recent advances, persistent challenges, and outline future directions to promote more equitable and transparent research practices in the study of Araripe’s fossil macroinvertebrates.

Brazilian Legal Framework On Fossil Heritage

Since the enactment of Decree-Law No. 4.146 in 1942, Brazilian legislation has classified fossil deposits - and, consequently, the fossils contained therein - as State property, subjecting the extraction of fossil specimens to prior authorization and oversight by the National Mining Agency (“Agência Nacional de Mineração” or ANM), then known as the National Department of Mineral Production (“Departamento Nacional de Produção Mineral”, or DNPM)(Decreto-Lei n. 4.146, 1942).

Additionally, since 1934, all Brazilian Federal Constitutions have consistently granted special protection to National Cultural Heritage, with the Brazilian Federal Constitution of 1988 (currently in force) explicitly including paleontological sites as part of this heritage (Article 216,caput, item V), and stipulating that any damage or threat to such sites may be punished by law (Article 216, §4) (Constituição da República Federativa do Brasil, 1988). Article 20 of the 1988 Brazilian Federal Constitution also defines State property, with its section I incorporating attributions as the one enshrined in Article 1 of Decree-Law No. 4.146. Due to their public property designation, Brazilian fossils are neither subject to transfer of ownership through sale executed by any other entity or individual, nor by adverse possession, in light of Article 102 of the Brazilian Civil Code (Lei n. 10.406, 2002), being of an unavailable, inalienable, and imprescriptible nature.

Strengthening even further the Brazilian Legislation and regulations on fossil extraction and collection, the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation (“Ministério de Ciência, Tecnologia e Inovação” or MCTI), under the authority granted by Decree No. 98.830 of 1990, issued Ordinance No. 55 of 1990, regulating the specific issue of the collection of data and scientific materials by foreign researchers(Decreto n. 98.830, 1990; Portaria n. 55, 1990). The Ordinance states, among other provisions, that (1) a Brazilian institution must co-participate in the research and specimen collection process; (2) this co-participating institution is responsible for requesting collection authorization from the relevant agency; (3) an authorization from the MCTI is required to conduct the study and export specimens; and (4) all holotypes of fossil species, at least 30% of the specimens of each identified taxon, and any specimens deemed to be of national interest must remain in Brazil at the co-participating institution. Lastly, for fossil exports, it is mandatory to complete the Export Registration in the SISCOMEX - Integrated Foreign Trade System (Portal Único Siscomex, n.d.) of the Federal Revenue Service (“Receita Federal”), which requires proof of prior approval from the National Mining Agency (ANM) (see NCM 9705.29).

Brazil is also a State Party to multiple international treaties, declarations, and instruments protecting cultural heritage at an international level, and regulating their trade, export, and import within national territories. Most notably, Brazil is a State Party to the 1970 UNESCO Convention on the Means of Prohibiting and Preventing the Illicit Import, Export and Transfer of Ownership of Cultural Property, incorporated into national law through Decree No. 72.312 in 1973. The Convention lists "objects of paleontological interest" amongst the categories of cultural property (article 1a) and, among other obligations, requires State-parties to prohibit their import, export and trade without proper authorization, to adopt measures to prevent their illicit trade and, where cultural property has been unlawfully exported, to recover and return it to the country of origin (in particular, Articles 2 to 8)(Decreto n. 72.312, 1973).

Historical legacies and scientific asymmetries

Fossil collection in the Araripe Basin has a long and uneven history. Vertebrate specimens were among the first to attract attention from foreign naturalists, with early records by Spix and Martius describing fossil fishes from the Romualdo Formation as early as the 1820s (Carvalho and Santos, 2005). In contrast, invertebrate fossils were largely overlooked until the mid-20th century, with the earliest records appearing in the 1950s (Costa-Lima, 1950). This delayed attention is partially explained by their prevalence in the Crato Formation, where fossils are exposed primarily through limestone quarrying rather than natural outcrops. As extractive activities expanded, scientific interest in macroinvertebrate fossils gradually increased.

After Costa-Lima (1950), over nine years passed before additional studies were published (Beurlen, 1964, 1966; Campos, 1986; Pinto and Purper, 1986; Martins-Neto, 1987b, 1988a, 1988b; Martins-Neto and Vulcano, 1988). Until then, the dragonfly Gomphaeschnaoides obliquus (Wighton, 1987) was the only species described, based on material from a foreign collection.

From 1990 on, the scenario changed; in Grimaldi (1990), several dozen insect taxa are described based in the American Museum of Natural History (AMNH), without Brazilian co-authors. They mention communications with the Museum of Zoology of the University of São Paulo (MZUSP) and Brazilian paleontologist Dr. Rafael G. Martins-Neto, expressing their intent to return some holotypes and other specimens to MZUSP - yet this material has not been sent to Brazil to date. Notably, both Wighton (1987) and Grimaldi et al. (1990) state that the fossils they described had been donated to AMNH by Herbert R. Axelrod, an American entrepreneur, philanthropist, and tropical fish enthusiast, who had a vast private fossil collection.

The number of invertebrate species described from Araripe increased significantly in the 1990s and 2000s. During this period, it was common for multiple new taxa to be described within a single publication. The higher proportion of holotypes in Brazilian collections for certain groups is directly linked to the research focus of some local paleontologists. For example, Dr. Rafael G. Martins-Neto specialized in Orthoptera and Neuroptera (Hessel et al., 2010), resulting in a greater number of type materials for these groups in Brazil. His trajectory illustrates the critical importance of home-grown research efforts, highlighting that researchers with local access to specimens can develop long-term research agendas.

Publications on arachnids and crustaceans began in the 1980s (Campos, 1986; Martins-Neto, 1987b). As with insects, local researchers started the studies, but foreign scientists were later drawn to the topic, attracted by the outstanding fossil material, leading to the description of new species based on specimens taken abroad. However, the pattern observed for arachnids and crustaceans is different. Most arachnid holotypes have been described from fossils deposited in Germany, without the collaboration of local scientists. In contrast, most crustacean holotypes were described by Brazilian researchers, particularly by scientists based in Northeast Brazil, where the Araripe Basin is located. The majority of these holotypes are also housed in Brazilian collections. Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in the number of described fossil crustacean species from Araripe. Approximately 70% of currently known species have been described in this period.

Regarding myriapods, only three species have been described to date, the first in 1998 (Martill and Barker, 1998). All holotypes are currently in Germany. In contrast, all known echinoderm and mollusks are deposited at the UFPE, in Recife, Brazil. Thus, while some invertebrate groups are currently well represented in Brazilian collections, many holotypes of Araripe macroinvertebrates remain housed abroad, limiting local access to primary fossil material.

These historical dynamics result in persistent asymmetries between researchers working in Global South fossil-rich regions–such as northeastern Brazil–and those affiliated with foreign institutions, particularly in Europe and North America. These imbalances extend beyond access to fossil specimens, affecting authorship, funding, institutional visibility, and control over research agendas. While often normalized in paleontological literature, such disparities reflect broader structures of colonialism– epistemic colonialism (see: Quijano 2000, 2007), in which scientific authority is concentrated in historically dominant institutions, often to the detriment of those working closest to the fossil sites. These asymmetries continue to shape how paleontological knowledge is produced, validated, and disseminated (Raja et al., 2022). They also expose the need to address the issue of data sovereignty: the principle that researchers and institutions based in the regions where fossils originate should have facilitated access to the materials and data necessary to develop autonomous, continuous, and high-quality scientific research–contributing directly to local scientific and institutional development (Dunne et al., 2025).

Scientific Colonialism: Patterns, Scale, Persistence, and Impact

Our results reveal a complex and deeply entrenched pattern of scientific colonialism in the study of fossil macroinvertebrates from the Araripe Basin. Despite Brazil’s long-standing legal framework that protects fossils as inalienable state property, nearly half of all holotypes described from the region are currently housed in foreign institutions. This pattern reflects not only historical imbalances in scientific exchange but also enduring forms of epistemic injustice, whereby institutions in the Global North disproportionately benefit from the paleontological heritage of the Global South (e.g., Raja et al., 2022).

A clear geographic pattern also emerges from our data. Consistent with the findings of Cisneros et al. (2022b), Germany hosts the largest number of Araripe macroinvertebrate holotypes (91), followed by the United States (83), with additional specimens held in France (15), Japan (12), and Italy (5). These concentrations highlight favored destinations for Brazilian fossils and further illustrate asymmetrical flows of scientific material.

The exclusion of Brazilian researchers from a substantial proportion of the analyzed publications–especially those involving holotypes stored abroad–illustrates these dynamics. Among the 225 macroinvertebrate holotypes held in foreign collections, 214 (95.1%) were described without Brazilian co-authorship. This finding aligns with earlier studies on vertebrate and plant fossils from Araripe (Cisneros et al., 2022b) and raises serious concerns about the continued marginalization of local scientists in research conducted on their own country’s fossil heritage.

Beyond authorship, limited access to the resulting literature compounds these inequities. Nearly half of the articles analyzed in this study (107 out of 218; 49.1%) were not openly available through the publishing journals or via the CAPES Federated Academic Community (CAFe) access. In most cases, this was due to paywalls imposed by the publishers, but 26 articles (11.9%) were also delisted or unavailable (see Appendix 3). As a result, much of the scientific production on Araripe macroinvertebrates remains inaccessible to Brazilian researchers–particularly those based at regional institutions with limited financial and digital resources. Restricted access to both specimens and literature reinforces existing asymmetries in scientific participation, validation, and reuse.

The high concentration of holotypes in Germany likely reflects a combination of historical, institutional, and commercial dynamics. Germany has a long-standing tradition of paleontological research on exceptionally preserved fossil Lagerstätten (Seilacher et al., 1985; Schultze, 1990), which likely increased interest in the Crato and Romualdo formations. Additionally, the legal framework in Germany contributes to a permissive attitude toward fossil trade. Fossil regulation varies by federal state (Länder), and in many cases, only scientifically or publicly valuable fossils are protected as cultural heritage (Bloos, 2004). Common fossils can often be collected and sold freely, especially in regions with commercial excavation activity. In these contexts, the sale of fossils is routine and legally permitted. While the export of fossils deemed important may require authorization at the state or federal level, the general permissiveness of fossil commerce has fostered a perception among some collectors and researchers that acquiring fossils from abroad is acceptable, even when the specimens originate from countries where fossil commercialization is prohibited.

Large international fossil and mineral fairs, such as the one held annually in Munich, and the Taipei Natural History Show, may also have attracted the export of Araripe fossils to Germany and other countries by providing a commercial platform that connected fossil dealers with collectors and institutional buyers (e.g., Bechly, 1997, 1998b). Importantly, the sustained interest of specific German researchers and institutions in Araripe fossils contributed to generating international demand for these specimens, effectively incentivizing their collection and commercialization. This demand was further facilitated by favorable currency exchange rates, which made institutions and private collectors from economically stronger countries preferred buyers in international fossil markets. This combined historical, legal, academic, economic, and commercial framework has helped normalize the presence of illicitly exported fossils in German collections. A similar combination of permissive trade environments, sustained academic interest, favorable purchasing power, and historical collecting practices may also help explain the high number of Araripe holotypes currently held in the United States, France, and Japan.

Our analysis also uncovered a systematic and persistent disregard for national legal requirements. None of the publications reviewed included information on collection or export permits, and in some cases, authors explicitly mention the purchase of fossil material–an act that contravenes Brazilian law. Additionally, the failure to repatriate holotypes following the enactment of Ordinance No. 55/1990 may also be interpreted as irregular, given the legal obligation to retain such specimens within national territory. As all publications analyzed were produced after the promulgation of Decree-Law No. 4.146/194, it is plausible that most fossil material–if not all– currently housed in foreign institutions was obtained in violation of Brazilian laws. That such patterns have persisted underscores not only failures in ethical practice but also the role of global scientific and editorial systems in normalizing research that may be based on illicitly acquired specimens.

Beyond legal and ethical obligations, the continued publication of studies based on unverified or illicit fossil material reflects deeper structural issues within the scientific publishing system. Journals and peer reviewers often fail to question the legal provenance of fossil specimens, largely because fossils are not universally recognized or treated as cultural heritage in editorial policies (Chacon-Baca et al., 2023). As a result, manuscripts are typically evaluated only for their scientific merit, with no scrutiny from heritage experts, legal advisors, or local researchers who could raise critical concerns about provenance and legality. This narrow focus allows questionable research practices to persist unchecked. Addressing these systemic flaws requires not only the adoption of clear editorial guidelines mandating documentation (such as collection and export permits) but also a critical rethinking of who is included in the peer review process. These blind spots have contributed to the systemic marginalization of source countries and the normalization of publishing research based on illicitly acquired material, even in high-profile international journals.

Additionally, our findings expose regional asymmetries within Brazil itself. While 53.9% of Araripe fossil holotypes are housed in national collections, the vast majority are located in institutions in the Southeast–particularly in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro states. In contrast, only 5.0% of holotypes are deposited in institutions within the Araripe region. This distribution reproduces internal hierarchies of scientific capital and institutional infrastructure, limiting the ability of local researchers and students to access, study, and curate the fossils of their own region. Such dynamics exemplify internal colonialism (Casanova, 1965; Chaloult and Chaloult, 1979), a concept whereby resource-rich peripheral regions are structurally subordinated to dominant centers of power and knowledge production within the same country. Thus, scientific colonialism operates not only across international borders but also through intra-national disparities between historically privileged and marginalized regions. A similar pattern of internal asymmetry in fossil access and institutional visibility has also been described by Regalado-Fernández et al. (2025).

Colonial practices in science are deeply rooted in an outdated perception that certain scientists or institutions have an inherent right to access and study fossils from other countries or regions without reciprocal benefits–an expression of epistemic colonialism, discussed above. Addressing these systemic issues requires a concerted effort to establish ethical guidelines and collaborative frameworks that ensure equitable participation of local researchers and benefit to local communities.

Beyond Holotypes

Our findings show that holotype-focused analyses capture only a fraction of the broader problem. Many studies rely on additional fossil material–often hundreds of specimens–for comparative, phylogenetic, taphonomic, evolutionary, or taxonomic purposes (Shear and Edgecombe, 2010; Barling et al., 2015; Lee, 2016; Wolfe et al., 2016; Bezerra et al., 2021). For instance, Barling et al. (2015) reported using 92 fossils donated to the University of Portsmouth, UK, by an individual who acquired them from a German seller. Many of the same authors expanded this study in 2021, analyzing 115 odonate specimens from the SMNS, 110 from Portsmouth, and 64 donated as part of a doctoral project (Barling et al., 2021). In this latter study, the authors emphasized that the 64 fossils from the doctoral project should be returned to Brazil, and these specimens have since been transferred to the MPPCN collection.

Similarly, Lee (2016) examined 981 specimens of fossil cockroaches, including 48 fossils from the SMNS and 933 from a German company. Lee identified 11 taxa, 4 of which were new species. The company had its material seized by the Public Prosecutor's Office of Kaiserslautern, Germany, following a report made by a Brazilian paleontologist to the Federal Prosecution Service of Brazil (Andrade, 2021).

In another example, Bechly (1998a) described six new species based on 205 adults and 104 naiad Odonata specimens, and although the repository of the holotypes and paratypes is clearly stated, it is also mentioned that the remaining specimens are in private collections from Germany.

The Issue With Private Collections

Although the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN, 1999) - http://iczn.org does not explicitly discourage private collections, Recommendation 72F (Article 72) highlights the principle of “institutional responsibility.” This guideline underscores the importance of ensuring specimen accessibility for study and of publishing lists of name-bearing types held in custody–practices that private collections frequently fail to implement. It is also worth noting that the Code explicitly states that for species described after 1999, the type material must be indicated in the publication with a statement that “they will be (or are) deposited in a collection plus a statement indicating the name and location of that collection” (Article 16.4.2), that is, if such information is not included, the description is not valid. Recommendation 16C also reinforces that the name-bearing types should be deposited in an institution that maintains a research collection.

In many cases, the scientific value of fossil specimens becomes reified through publication, regardless of whether the physical specimens are traceable or accessible. This dynamics risks treating peer-reviewed papers as sufficient evidence in themselves–even when the holotype material is held inaccessible or its whereabouts are unknown. Such cases undermine taxonomic stability, as hypotheses based on unverifiable specimens cannot be independently tested or replicated. From an epistemological perspective, this reflects a reification of the publication process, in which scientific validity becomes anchored in an author’s prestige and journal status rather than empirical verifiability. This is a central feature of epistemic colonialism: the assumption that knowledge becomes legitimate merely by being published by researchers from dominant regions, even when the material evidence is inaccessible. In addition to these concerns, restricted access to materials also creates barriers for the general public, further limiting their engagement with scientific knowledge (Baker, 2016; Stark, 2018).

Among the holotypes discussed in this study, 18 (3.7%) were described based on fossils from private collections outside Brazil. Below, we summarize available information regarding their current repositories and situation:

1. The private collection of Mr. Jörg Wunderlich (Hirschberg, Germany) houses two holotypes of fossil arachnids: Cratosolpuga wunderlichi Selden, 1996, and Seldischnoplura seldeni Raven et al., 2015. In both publications, the location of the collection is indicated as the private collection of Mr. Jörg Wunderlich. In the Cratosolpuga publication, the authors state that the location is Straubenhardt, Germany. In the Seldischnoplura article, however, the location is given as Hirschberg, Germany. On Mr. Wunderlich's personal website (Wunderlich, 2018), he refers to a “Private Laboratory of Arachnology” located at his home address in Hirschberg, which likely corresponds to the current repository of both specimens.

2. The Baraffe Collection (Paris, France) is listed as the repository of the holotype of the odonate Araripegomphus cretacicus Nel and Paicheler, 1994; the authors state this specimen had no collection registration number at that time.

3. The Kurt Rumbucher Collection (location unknown) was identified as a repository by himself when he described two new species of neuropterans: Brasilopsychopsis kandleri Rumbucher, 1995, and Cratopsychopsis maiseyi Rumbucher, 1995. The same publication lists an additional 25 insect specimens from his personal collection but provides no further details on their status or location. Even though the location of the collection is unknown (Martins et al., 2023), this does not seem to impact the validity of the descriptions in ICZN terms, as they were published prior to 1999.

4. The Masayuki Murata Collection (Kyoto, Japan) contains four insect holotypes:Anomalaeschna berndschusteri Bechly et al., 2001 (Odonata); Cordulagomphus (Procordulagomphus) michaeli Bechly, 2007 (Odonata);Cratohexagenites longicercus Staniczek, 2007 (Ephemeroptera) and Cretoscolia brasiliensis Osten, 2007 (Hymenoptera). In the descriptions, all of these are indicated as deposited in “MURJ” (Murata Collection); Bechly (2007, p.146) indicates that some specimens from this collection are now at KMNH. There was a repatriation request for Cretoscolia brasiliensis, which was archived in 2016 (MPF-CE, 2016).

5. The private collection of Cristian Pella (Verbano Cusio Ossola, Italy) contains the holotype of Cratocroce araripensis Nel and Pella, 2020a (Neuroptera) and Araripenepa vetussiphonis Nel and Pella, 2020b (Hemiptera).

6. The private collection of Markus Sennlaub contains seven new species (including Odonata, Orthoptera, Hymenoptera, and Neuroptera) that were described between 2020 and 2022 (Nel and Pouillon, 2020; Jouault et al., 2020, 2021; Jouault and Nel, 2021a,b; Nel and Jouault, 2021). Valdiphlebia sennlaubi Nel and Pouillon, 2020 (Odonata). Curiosivespa sennlaubi Jouault et al., 2021 (Hymenoptera) was deposited in a museum (MHNE, Colmar, France), but the exact location of the remaining collection is unknown. Cratosirex sennlaubi Jouault et al. 2020 (Hymenoptera), Prosyntexis sennlaubi Jouault and Nel, 2021a (Hymenoptera), and Paraneliana sennlaubi Jouault and Nel, 2021b (Neuroptera) are indicated in their descriptions as to be donated to MHNE (Colmar, France) by the owner or upon the private collection owner’s death (Jouault et al., 2020; Jouault and Nel, 2021a,b; Martins et al., 2023). Cratoelcana rasnitsyni Nel and Jouault, 2021, and Pseudoacrida sennlaubi Nel and Jouault, 2021 (Orthoptera) are indicated as belonging to Sennlaub's private collection and that “will be deposited in a museum in Brazil” (Nel and Jouault, 2021); however, the lack of information regarding the location of either case indicates these likely constitute nomina nuda based on ICZN art. 16.4.2.

Recently, specimens from a private collection based in Switzerland were donated to MN-UFRJ by the Interprospekt Group, representing the Burkhart Pohl family. The lot comprises 1,104 fossils, including crustaceans and insects (Brasil, 2024). The Interprospekt Group maintains the Wyoming Dinosaur Center, which is a repository for some of the holotypes from the Araripe Basin (e.g., Appendix 2), but at this time, it is not known if the material donated includes holotypes.

Carvalho (1993) listed 20 insect specimens that were, at the time, deposited in Brazilian private collections. Since then, several of them were donated to museums. Martins et al. (2023) state that the majority of fossil arthropods from private collections in Brazil are now kept in public institutions. The known status of these collections is listed below:

1. The Vulcano Collection, with 44 holotypes and a large number of other fossils, was transferred to MZUSP in 2018 (Duarte and Silveira, 2023).

2. The Desirée Collection was donated to MN-UFRJ in 2001, and all specimens were registered in the paleobotany, paleovertebrate, and paleoinvertebrate collections (Sandro Scheffler, personal commun., 2024).

3. The Martins-Neto Collection used to be located in the office of the Brazilian Society of Paleoarthropodology and was transferred to the DNPM (ANM) office in Crato, Ceará. In 2020, however, the DNPM (now ANM) office was closed, and part of the material was transferred to UFABC, MPPCN, and USP-Ribeirão Preto (Martins et al., 2023; Max C. Langer, personal commun., 2023).

4. There is no information regarding the specimens that were in the Museu de Paleontologia ‘Força da Terra’ in São Paulo (see the discussion below).

The absence of clear information regarding the status or location of some collections and specimens prevents their verification or access. In such cases, where specimens are either untraceable, kept in inaccessible private holdings, or promised for future deposit without fulfillment, we argue that these names should be considered nomina nuda, as they do not meet the requirements for scientific reproducibility or institutional transparency.

Illegal Fossil Trafficking: Market Dynamics and Institutional Complicity

The illegal trade of Araripe fossils is not an isolated issue but part of a broader, economically motivated global phenomenon affecting paleontology and cultural heritage protection. This trade is shaped by scientific demand, collector preferences, and institutional complicity. One of the most striking examples is the case of Burmese amber, which rapidly became a highly desirable commodity following the publication of some high-profile fossils (e.g., Xing et al., 2015, 2016, 2018, 2020; Yu et al., 2019), even though its extraction and commercialization have been linked to violent conflicts in Myanmar (UN, 2019; Dunne et al., 2022). Similarly, in Morocco, strong market demand for particular types of fossils has led to the fabrication of specimens and mislabeling of provenance to match desirable localities (see: Sharpe et al., 2024).

In the case of macroinvertebrates, market preferences also seem to significantly influence scientific output. Highly recognizable and aesthetically appealing fossils, such as dragonflies (Odonata), are more likely to attract foreign collectors and curators. In contrast, more ambiguous, fragmentary, or less charismatic groups–such as echinoderms, crustaceans, or even orthopterans–tend to receive less attention. This market-driven selectivity not only affects which specimens are collected and exported but also introduces significant biases in the scientific representation and understanding of these groups. When commercial acquisitions replace systematic fieldwork, the result is a distorted representation of fossil diversity, ultimately affecting our broader understanding of past biodiversity.

In Araripe, these economic dynamics fostered the development of a multimillion-dollar fossil market (Fernandes and Angelo, 2002; FOLHA, 2004; TRF-3, 2014), structured to meet international demand. Reports of illegal Araripe fossil trade have been circulating in the media since the 1990s and cited in scientific papers since the 1980s (e.g., Silva and Arruda, 1984). Interviews with Brazilian researchers have repeatedly highlighted both how widespread this trade was between 1980 and 1990 and the conflicting views on the commercialization of fossils. For example, Dr. Maria Aparecida Vulcano described how fossils were openly sold at Praça da República in São Paulo during the 1980s, having been transported in shipments concealed in trucks carrying other goods, such as alcoholic beverages. According to her, some fossils arrived in São Paulo with designated consignees, while others, lacking specific recipients, were more frequently sold to foreign buyers, “often Americans” (Fontes, 1996). In another interview, Dr. Martins-Neto acknowledged that his research would not have been possible without access to fossils provided by a dealer in São Paulo. He even claims that the AMNH was among the institutions that most frequently acquired fossils to be taken to the United States (Angelo, 2001).

These commercial circuits were supported by local and international actors. There is a series of legal cases filed or still ongoing in Brazilian courts, and a few are particularly noteworthy due to the amount of material mentioned in the reports, spanning thousands of specimens. One such case concerns the fameless ‘Museu de Paleontologia Força da Terra’ in São Paulo (SP) (Fernandes and Angelo, 2002; FOLHA, 2004). This private institution previously held nine holotypes of fossil insects from Araripe, the current location of which is unknown (Martins-Neto, 2003, 2005b; Ruf et al., 2005). Part of this material was temporarily transferred to the Paleontology Museum of UNESP (Rio Claro, SP) after Federal Police intervention; however, the specimens were subsequently returned to the dealer through a court decision, and their final whereabouts remain unclear (Corradini, 2006).

Another prominent example is the German company m.s.-fossil (Bechly, 1997, 1998b), which not only commercialized Araripe fossils but also allegedly offered the right to name new species until the year 2000 (Fernandes and Angelo, 2002; Pessoa, 2007). This company reportedly operated within a transnational network that included a museum collection in the United States (Nascimento, 2014).

These cases illustrate that the illegal trade of fossils is not merely a matter of “weak enforcement” but a reflection of deeper systemic forces. It reflects a scientific economy in which market demand influences what is collected, described, and valued globally. Institutions such as museums and universities are not passive recipients in this process; they actively legitimize and valorize illicitly obtained material through acquisition, publication, funding, and exhibition. As such, they must assume greater ethical responsibility. The Araripe fossil trade serves as a compelling case study of how economic and institutional interests converge to perpetuate extractive models of science that reinforce biases in our understanding of past biodiversity and marginalize local communities.

Advancements, Challenges, and Recommendations

One of the most significant advancements in the protection of Araripe’s fossils has been UNESCO’s recognition of Araripe Geopark in 2006, which has helped promote ecotourism, educational outreach, and the preservation of the region’s paleontological heritage. This designation has strengthened local efforts to prevent illegal fossil trade while also fostering community engagement in conservation initiatives (Vilas-Boas et al., 2013).

Over the past decade, discussions surrounding the legal and ethical actions involving Araripe Basin fossils have gained significant international media attention (e.g., Ortega, 2021; Lenharo and Rodrigues, 2022; Warren and Price, 2023). The active involvement of the local scientific community, combined with public engagement through social media, has played a crucial role in efforts to protect and repatriate Brazilian fossils (e.g., Cisneros et al., 2021, 2022b; Kashani et al., 2024). Among the most notable cases are the return of the ‘Ubirajara’ specimen, the first feathered non-avian dinosaur fossil ever discovered in the basin. Its repatriation was a landmark event in the fight against local fossil trafficking and influenced the repatriation of other fossil specimens (Stewens, 2023). Following this case, additional fossils were successfully returned to Brazil, including the holotype of the spider Cretapalpus vittari Downen and Selden, 2021 - along with 35 other fossil spiders -, originally housed at the KUMIP (Freitas, 2021). After witnessing the ‘Ubirajara’ repatriation campaign on social media, the primary author engaged in a dialogue with Brazilian researchers and facilitated a formal agreement between KUMIP and MPPCN, leading to the successful repatriation of these specimens to Brazil (Leite, 2021; Queiroga, 2021).

Before the 'Ubirajara' case, Brazil's Federal Public Prosecutor's Office had been actively engaged in efforts to repatriate fossils illicitly trafficked out of the country, often based on reports from Brazilian researchers. One significant case involved the seizure of 998 fossils in France in 2013, including many fossil insects, which had been illegally extracted from Brazil's Araripe Basin. The heightened public awareness and international attention generated by the 'Ubirajara' campaign played an important role in facilitating the Ceará state government's decision to allocate funds for the repatriation of these fossils (Secom-PGR, 2022).

Since the ‘Ubirajara’ case, the Federal Prosecution Service, in partnership with MPPCN and in response to Brazilian researchers' reports, has additionally initiated multiple requests for the repatriation of Brazilian fossils from Europe and the United States. Parallel to these actions, increased law enforcement efforts have also been implemented since 2022 to improve monitoring of mining activities and curb illicit fossil trade (Ascom-PMCE, 2023a, 2023b, 2024a, 2024b; Ascom-SSPDS, 2024). The Environmental Military Police has conducted targeted operations in local limestone quarries, leading to the seizure of hundreds of fossils, many of which were insect specimens, all of which were transferred to MPPCN.

The Brazilian Society of Paleontology (SBP) has also taken a more proactive stance over the past decade, strengthening its advocacy for fossil repatriation. In collaboration with its associates and federal authorities, SBP has worked to demand the return of specimens held in foreign institutions while also engaging in dialogue with researchers, scientific societies, and journal editors to improve publication policies (Araújo-Júnior et al., 2024).

Public engagement campaigns have further contributed to local fossil protection efforts. Initiatives such as “Lugar de Fóssil é no Museu” (“Fossils belong in Museums”), promoted by MPPCN, have successfully encouraged private individuals to voluntarily return fossils to local institutions, leading to the recovery of over 1,050 specimens (Ascom-URCA, 2020). This initiative highlights the effectiveness of educational outreach in fostering public awareness about fossil conservation and repatriation.

Despite these advancements, fossil repatriation and protection remain complex and often controversial topics. Some Brazilian researchers have emphasized the role of foreign institutions in disseminating knowledge about Brazil’s geological heritage internationally (e.g., Carvalho et al., 2021), which may be interpreted as tacit acceptance of fossil collections remaining abroad. While such perspectives often aim to highlight Brazil’s paleontological significance on the global stage, they raise concerns about normalizing the long-standing removal of specimens in disregard of local laws, ultimately legitimizing both historical and ongoing cases of illegal fossil trafficking. This is particularly problematic given that many of these specimens are not publicly exhibited, but rather kept in restricted-access research collections–rendering them invisible to both the Brazilian public and the international community. Even when displayed, they are often accompanied by signage that emphasizes foreign expeditions or collectors, frequently omitting or misrepresenting the fossil’s true provenance. This not only fails to acknowledge Brazil’s scientific and cultural contributions but also reinforces extractivist narratives that glorify scientific appropriation and obscure local agency. In this light, justifying the retention of Brazilian fossils abroad may ultimately perpetuate the same colonial dynamics that repatriation efforts seek to dismantle. This ongoing debate reflects broader challenges related to fossil accessibility, research equity, and the role of national heritage in fostering scientific development within local communities and institutions.

Complicating the matter further is the resurgence of debates on the commercialization of fossils in Brazil. Organizations, such as the Brazilian Federation of Geologists (“Federação Brasileira de Geólogos” or FEBRAGEO), advocate for the regulation of fossil sales. The debate centers on whether the current legislation should be revised to allow controlled commercialization of common fossil specimens. FEBRAGEO argues that fossils should be classified as part of Brazil’s mineral heritage, which would permit their regulated sale (Kuhn, 2025). On the other hand, SBP, with the support of its associates, contends that fossils are and should remain regarded as natural and cultural heritage, emphasizing their scientific and historical value (Araújo-Júnior et al., 2024). They caution that commercializing fossils–even under regulation–risks irreversibly compromising scientific data and weakening conservation efforts. Regulating the sale of so-called “common” fossils is unlikely to deter the illegal trade in rare or scientifically valuable specimens. The fossil market is driven by scarcity and uniqueness: specimens perceived as new species or with exceptional preservation command significantly higher prices than generic material. As such, collectors and traders will continue to target unique fossils, regardless of regulatory frameworks that only apply to common ones. This market logic creates a feedback loop in which economically attractive taxa are prioritized for collection, reinforcing extraction biases in what is preserved, curated, and ultimately studied. Recognizing fossils as mineral commodities would not mitigate trafficking; instead, it risks legitimizing existing asymmetries and further entrenching extractive practices–ultimately undermining efforts toward equitable, ethical, and scientifically grounded fossil heritage management.

Brazil’s paleontological landscape has evolved significantly since the early days of research in Araripe. The number and diversity of active research groups have grown steadily, supported by national and state-level initiatives, particularly the expansion of higher education in Brazil, between 2000 and 2015 (Bello, 2025). This period saw the creation of new tenure-track faculty positions and increased availability of research funding and scholarships, which collectively contributed to the strengthening of paleontological research across the country, including in historically underfunded regions.

In recent years, the government of Ceará state has taken an especially active role in supporting local paleontological infrastructure. Following the international repercussions of the ‘Ubirajara’ repatriation campaign, the state allocated significant financial resources–totaling millions of reais–to local institutions and research groups in the Araripe region (Leite, 2025). These investments have enabled the consolidation of multiple paleontological research teams in the area, further reducing the need to export fossils for study and helping foster local scientific and economic development.

We advocate for the preservation of these specimens as close as possible to their collection sites, recognizing that museums and research centers can be drivers of local sustainable development (Guimarães, 2012; Sheppard, 2013; Barreto et al., 2016; Gustafsson and Ijla, 2017). This potential is particularly evident in the Araripe region, where several studies have demonstrated how paleontological heritage contributes to socioeconomic transformation and promotes more symmetrical collaborations between scientists and local communities. For example, Pinheiro and Silva-Júnior (2021), Fernandes et al. (2024) and Barros (2025) describe how MPPCN directly fosters geotourism and socioeconomic development in the area through scientific outreach and community engagement. Soares et al. (2018) and Leal et al. (2023), in turn, emphasize the role of Araripe UNESCO Global Geopark in promoting cultural revitalization, stimulating the regional economy, and supporting environmental conservation. In particular, Leite (2024) highlights the importance of paleontological handicrafts as a means of strengthening tourism and creating alternative income sources for local artisans–underscoring the broader socioeconomic impact of paleontology-driven initiatives in the region.

A particularly innovative example is provided by Machado-Filho and Oliveira (2024), who developed an educational and artisanal initiative in Santana do Cariri using fossil replicas made from powdered Pedra Cariri limestone, a byproduct of local quarrying. Originally commercialized, these replicas were later incorporated into formal education settings, contributing to heritage education, raising environmental awareness, and reconnecting the community with its fossil legacy. The project aligns with Municipal Law No. 954/2021, which mandates fossil education in local schools, and was supported by MPPCN (Lei Municipal n. 954, 2021). It illustrates how scientific engagement, artisanal knowledge, and educational policy can converge to foster inclusive, community-centered paleontological heritage management.

These developments demonstrate that meaningful change can be achieved through inclusive policies, community engagement, and institutional investment. They also demonstrate viable paths for fostering symmetrical collaborations between science and society. However, advancing a more equitable and ethical model of paleontological research will also require change from within the scientific establishment itself.

A critical area for improvement lies in scientific publishing. Journal editors, peer reviewers, and publishers should continue to strengthen transparency requirements regarding data sources, specimen provenance, research permits, and conflicts of interest. These policies, which have been particularly scrutinized in biomedical research (Lo and Field, 2009), could greatly benefit paleontology by ensuring greater accountability in fossil-related studies.

Some funding agencies have already implemented mandatory research ethics training for new grant recipients, while governmental bodies increasingly deny permit renewals to researchers who fail to meet reporting requirements for extant species collected and especially samples to be sent abroad (Lei n. 13.123, 2015; Portaria n. 1, 2017; Portaria n. 748, 2022). With the growing prevalence of online publishing, the demand for verifiability in research has increased, and applying these standards to paleontology would enhance both scientific integrity and data reproducibility.

Some recent examples underscore the growing pressure on journals to adopt stricter compliance policies. Notably, after widespread criticism of research on Myanmar amber–due to its links with armed conflict and human rights violations–several journals implemented bans or introduced stricter submission requirements for such material (Dunne et al., 2022). These editorial responses demonstrate that journals hold significant power and responsibility in defining the ethical boundaries of scientific publication. Yet, in paleontology, most journals remain reluctant to address cases of fossil illegal trafficking, even when the material lacks legal provenance or when national laws have clearly been violated. We recommend that journals adopt explicit policies requiring documentation of collection and export permits for fossil specimens, and that such information be made available during peer review and publication.

CONCLUSIONS

This study presents a comprehensive analysis of the legal, ethical, and epistemic challenges associated with the collection, study, and deposition of fossil macroinvertebrates from the Araripe Basin. Despite long-standing Brazilian legislation that classifies fossils as inalienable State property and prohibits their export without formal authorization, nearly half of all holotypes analyzed are currently held in foreign institutions. The vast majority of these specimens were described without the involvement of Brazilian researchers, reflecting persistent asymmetries in authorship, access, and scientific recognition.

These patterns are not isolated anomalies but symptomatic of a broader framework of scientific colonialism, in which research capital, institutional prestige, and specimen control are disproportionately concentrated in the Global North. Internal disparities within Brazil, particularly the marginal representation of Araripe institutions in the curation of local fossil material, further compound this exclusion. Additionally, limited access to key publications and the continued reliance on private collections–many of which lack transparency or appropriate curation–pose further barriers to equitable and reproducible science.

While recent initiatives have achieved progress in fossil repatriation, public engagement, and regulatory enforcement, structural challenges persist. A more comprehensive transformation is needed–one that integrates more ethical publication policies, verifiable specimen provenance, and inclusive international collaboration. Ensuring that fossil heritage remains accessible to, and benefits, the communities from which it originates is also a critical step toward fostering a more just and equitable scientific landscape.

Looking forward, the future of research on Araripe fossil macroinvertebrates depends on expanding equitable access to specimens, data, and publications. Strengthening local research infrastructure, fostering international collaborations based on mutual benefit, and enforcing ethical standards in scientific publishing are critical next steps. Targeted investments in Northeast Brazil could help reverse historical imbalances and ensure that macroinvertebrate paleontology contributes not only to academic knowledge but also to local development and heritage preservation. Reframing research agendas to center on regional leadership, legal compliance, and scientific transparency will be key to building a more inclusive and sustainable future for paleontological studies in the Araripe Basin.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their suggestions and adjustments. We would also like to thank the Palaeontologia Electronica team for their careful attention to the publication process. We would like to thank Dr. John D. Oswald, creator of the Lacewing Digital Library, and the Permanent Committee of the International Conferences on Ephemeroptera, for their efforts to facilitate access to an important scientific bibliography of paleoinvertebrate studies and entomology. We would like to thank all the scientists, civil servants, and the general public who have helped us in our efforts to make paleontology more ethical and accessible. The authors would like to thank the agencies that granted funds and scholarships to the authors. Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - CNPq: Macário, M.A. (PIBIC/CNPQ-157336/2024-7); Ghilardi, A.M. (CNPq/303719/2025-7). Fundação Cearense de Apoio ao Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico - FUNCAP: Aureliano, T. (FPD-0213-00295.01.01/23); Lima, D. (PV1-0187-00019.01.00/21); Pinheiro, A.P. (BP6-0241-00240.01.00/25). Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior - CAPES: Santana, E.M.G. and Santos, E.S. (CAPES-88887.738154/2022-00).

REFERENCES

Andrade, R. de O. 2021. No rastro dos fósseis contrabandeados. Revista Pesquisa Fapesp.

https://revistapesquisa.fapesp.br/no-rastro-dos-fosseis-contrabandeados/

Angelo, C. 2001. Paleontologia: Tráfico de fósseis pode ter 1a condenação. Folha de São Paulo.

https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/fsp/ciencia/fe0107200105.htm

Araújo-Júnior, H.I. de, Ghilardi, R.P., Ribeiro, V.R., Ribeiro, A.M., Barbosa, F.H. de S., Negri, F.R., and Scheffler, S.M. 2024. Scientific societies have a part to play in repatriating fossils. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 8:355–358.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41559-023-02296-2

Ascom-PMCE. 2023a. BPMA da PMCE recolhe três fósseis em pedreiras da cidade de Nova Olinda. Polícia Militar do Estado do Ceará.

https://www.pm.ce.gov.br/2023/07/18/bpma-da-pmce-recolhe-tres-fosseis-em-pedreiras-da-cidade-de-nova-olinda/

Ascom-PMCE. 2023b. Polícia Militar recolhe 27 fósseis durante fiscalizações em pedreiras. Governo do Estado do Ceará.

https://www.ceara.gov.br/2023/09/22/policia-militar-recolhe-27-fosseis-durante-fiscalizacoes-em-pedreiras/

Ascom-PMCE. 2024a. Polícia Militar recolhe 13 fósseis durante fiscalizações em pedreiras nos municípios de Nova Olinda e Santana do Cariri. Secretaria da Segurança Pública e Defesa Social.

https://www.sspds.ce.gov.br/2024/02/08/policia-militar-recolhe-13-fosseis-durante-fiscalizacoes-em-pedreiras-nos-municipios-de-nova-olinda-e-santana-do-cariri/

Ascom-PMCE. 2024b. PMCE recolhe 15 fósseis durante fiscalizações em pedreiras no Cariri. Secretaria da Segurança Pública e Defesa Social.

https://www.sspds.ce.gov.br/2024/07/04/pmce-recolhe-15-fosseis-durante-fiscalizacoes-em-pedreiras-no-cariri/

Ascom-SSPDS. 2024. PMCE recolhe 15 fósseis durante fiscalizações em pedreiras de Nova Olinda e Santana do Cariri. Governo do Estado do Ceará.

https://www.ceara.gov.br/2024/12/04/pmce-recolhe-15-fosseis-durante-fiscalizacoes-em-pedreiras-de-nova-olinda-e-santana-do-cariri/

Ascom-URCA. 2020. Campanha "Lugar de Fóssil é no Museu" já obteve 1050 fósseis para Museu Plácido Cidade Nuvens. Governo do Estado do Ceará.

https://www.ceara.gov.br/2020/01/22/campanha-lugar-de-fossil-e-no-museu-ja-obteve-1-050-fosseis-para-museu-placido-cidade-nuvens/