Review: The Bearded Lady Project. Challenging the Face of Science

Article number: 25.2.a3R

July 2022

Marsh, Lexi Jamieson and Currano, Ellen, editors. 2020, Columbia University Press. 181 pages. ISBN: 9780231198042. $40 from the publisher and $22.25 Amazon

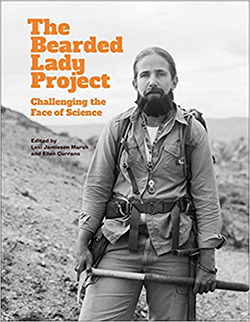

This book represents the capstone of both a fruitful and inspiring collaboration that began in 2014. Discussing around dinner on the gender biases still plaguing their respective fields, paleontologist Ellen Currano and filmmaker Lexi Jamieson Marsh laughed at the idea of having to put on a beard to solve their problems. This “wry joke” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. xvii) rapidly grew into a more serious topic of reflection and investigation. How could the addition of facial hair be associated with the acquisition of scientific status, even in the context of an informal conversation? How and when did having a beard become a criterion to recognize scientific ability and authority? Unexpectedly, a cathartic joke turned into a powerful heuristic tool. During the spring and summer of 2014, Marsh and Currano launchedThe Bearded Lady Project. They would ask women working in paleontology to be photographed in the field or in their laboratories while wearing fake beards. The beard-joke would serve as an effective icebreaker on issues related to gender inequalities and pervasive stereotypes in paleontology, and the field sciences in general. In just a few years, Marsh and Currano assembled an absolute lore of stunning, provocative black-and-white portraits, as well as a precious series of personal testimonies. Eventually, the collaboration grew into a multi-faceted project leading to the creation of a website (https://thebeardedladyproject.com/), the design of a touring exhibition, and the production of an almost hour-long documentary. The book effectively retraces some of the major steps of The Bearded Lady Project in essays penned by Marsh.

This book represents the capstone of both a fruitful and inspiring collaboration that began in 2014. Discussing around dinner on the gender biases still plaguing their respective fields, paleontologist Ellen Currano and filmmaker Lexi Jamieson Marsh laughed at the idea of having to put on a beard to solve their problems. This “wry joke” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. xvii) rapidly grew into a more serious topic of reflection and investigation. How could the addition of facial hair be associated with the acquisition of scientific status, even in the context of an informal conversation? How and when did having a beard become a criterion to recognize scientific ability and authority? Unexpectedly, a cathartic joke turned into a powerful heuristic tool. During the spring and summer of 2014, Marsh and Currano launchedThe Bearded Lady Project. They would ask women working in paleontology to be photographed in the field or in their laboratories while wearing fake beards. The beard-joke would serve as an effective icebreaker on issues related to gender inequalities and pervasive stereotypes in paleontology, and the field sciences in general. In just a few years, Marsh and Currano assembled an absolute lore of stunning, provocative black-and-white portraits, as well as a precious series of personal testimonies. Eventually, the collaboration grew into a multi-faceted project leading to the creation of a website (https://thebeardedladyproject.com/), the design of a touring exhibition, and the production of an almost hour-long documentary. The book effectively retraces some of the major steps of The Bearded Lady Project in essays penned by Marsh.

The Bearded Lady Project is a beautiful catalogue of black-and-white photographs, including more than 50 portraits and short essays. The essays are organized across three main sections, respectively titled, “Why Challenge the Face of Science”, “Women in Paleontology”, and “Behind the Lens”.

The first section lays out a series of justifications for The Bearded Lady Project . It includes introductory essays on what paleontology is, and the different places in which paleontologists carry their work. These two essays signal the intention of Marsh and Currano to have their message reach beyond the fields of paleontology. Nonetheless, additional essays discussing the history of bearded women as a scientific curiosity as well as the “lost legacy” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. 28) of women in paleontology demonstrate the editors’ intention to educate the paleontological community about the historicity of gender biases in science and in their own discipline. From this first section, the reader understands thatThe Bearded Lady Project is an attempt at reintegrating women in the visual landscape of paleontology while reinventing the visual codes that have informed the problematic, exclusive identity of paleontologists until now. As Currano puts it, “Black-and-white portraits of past paleontologists continue to make a lasting and often outdated impression on the field of paleontology. These images are memorable and stereotypical: male colonizers standing beside their dinosaur bone trophies, their unkempt beards badges of honor for time spent in the field.” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. 28)

The second collection of essays, “Women in Paleontology”, is certainly, apart from the images themselves, the most powerful segment of the book. It includes testimonies from 12 paleontologists who participated in The Bearded Lady Project . The value of this section derives in great part from the diversity of professional trajectories and generations represented. These short biographical essays provide the reader with the opportunity to learn directly from people who had to find their place within a field traditionally dominated by men. Some of them focus on the struggle against expectations and stereotypes; most highlight the unexpected support and opportunities that were found along the way; all contribute to a wide range of perspectives on education, academia, fieldwork, mentorship, teaching, and personal life, which allows the reader to build a more holistic vision of paleontology as a professional field and community. The section ends with an optimistic message by paleontologist Sara B. Pruss, stressing the progress that has been made since she entered the field: “We have much work to do as a community, but I think we are moving toward a place where we can take off the beards for good.” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. 145)

The ambition to provide the paleontological community with the tools to pursue its efforts toward more inclusivity and diversity is once again illustrated by essays on the definition of “woman” and “gender”, as well as on the concept of gender performativity. Punctuating the second section, these essays constitute an introduction to key questions and distinctions discussed by social scientists and philosophers. In this regard, the book serves to popularize gender studies research among the scientific community. Such popularization is most welcome considering the recurrent, widespread misrepresentation affecting that scholarship. In this regard, The Bearded Lady Project could prove to be a valuable resource in undergraduate and graduate courses to foster students’ awareness on issues related to gender, diversity, representation, and fairness within science.

The third section of the book, “Behind the Lens”, consists of four essays delving into and reflecting on the making of the photographs, the interviews, and the documentary. Marsh shares her intellectual and emotional journey through the evolution of the project. She humbly acknowledges that, despite her close friendship with Currano, she was nowhere near facing the same risks as her: “She knew her colleagues would be watching, and that what she said would follow her and potentially discredit her research.” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. 153) Such an observation forces the reader to better appreciate the courage, generosity, and artistry it took for this project to come to fruition. In her essay, Currano reflects on her interactions in the field with cinematographer Draper White and how they enabled her to “think more deeply about [her] science.” (Marsh and Currano, 2020, p. 157) Finally, portrait photographer Kelsey Vance shares the technical aspects and artistic choices behind the black-and-white portraits.

Something needs to be said about howThe Bearded Lady Project represents a formidable example of the kind of meaningful breakthrough the collaboration between artists and scientists can achieve. More importantly, the historical awareness with which Marsh, Currano, and their team have run the project clearly shows that the identity and social structure of scientific fields, and especially those as popular as paleontology, are inevitably informed by their representations. Harnessing the power of artistic mediums is and will continue to be of critical importance to encourage sustainable changes toward more diversity and equality within paleontology and the geosciences. We can only hope that The Bearded Lady Project will serve as a source of inspiration for future interdisciplinary collaborations looking for more inclusive ways of teaching, researching, and communicating on the deep history of life.