Upper Jurassic sauropod record in the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal): Geographical and lithostratigraphical distribution

Upper Jurassic sauropod record in the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal): Geographical and lithostratigraphical distribution

Article number: 20.2.27A

https://doi.org/10.26879/662

Copyright Society for Vertebrate Paleontology, June 2017

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Submission: 21 March 2016. Acceptance: 1 May 2017

{flike id=1865}

ABSTRACT

Sauropod remains are relatively abundant in the Upper Jurassic sediments of the Lusitanian Basin. These dinosaurs are recorded in several sub-basins formed during the third rifting episode related to the evolution of the Lusitanian Basin. The Kimmeridgian-Tithonian sedimentary sequence is dominated by siliciclastic deposits, indicating a continental environment. Sauropods are present all along this mainly terrestrial sequence, being recorded in the Alcobaça, Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo, Sobral, Freixial, and the Bombarral Formations, ranging from the early Kimmeridgian to the late Tithonian. Sauropoda is the most abundant dinosaur group in the Upper Jurassic fossil record of the Lusitanian Basin and is especially well-represented in the Bombarral and Turcifal Sub-basins. Several new specimens, so far unpublished, are reported here. The sauropod fauna identified mainly includes non-neosauropod eusauropods (including turiasaurs), diplodocoids (some specimens with diplodocine affinities), basal macronarians (non-camarasaurids and camarasaurids), and titanosauriforms (some specimens with brachiosaurid affinities). Macronarians, turiasaurs and diplodocoids are generally present along the entire Kimmeridgian-Tithonian continental to transitional deposits of the Lusitanian Basin, but the known fossil record for some more exclusive groups such as camarasaurids, brachiosaurids, and diplodocines, present a more restricted stratigraphic distribution.

Pedro Mocho. The Dinosaur Institute, Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County, 900 Exposition Blvd., 90007 CA, Los Angeles, USA; Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain; Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. pmocho@nhm.org

Rafael Royo-Torres. Fundación Conjunto Paleontológico de Teruel-Dinópolis/Museo Aragonés de Paleontología, av. Sagunto s/n. E-44002 Teruel, Spain. royo@dinopolis.com

Fernando Escaso. Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain; Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. fescaso@ccia.uned.es

Elisabete Malafaia. Instituto Dom Luiz, Universidade de Lisboa. Edifício C6, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal; Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência, Rua da Escola Politécnica 56/58, 1250-102 Lisboa, Portugal; Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. emalafaia@gmail.com

Carlos de Miguel Chaves. Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain. carlos.miguelchaves@gmail.com

Iván Narváez. Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain. i.narvaez.padilla@gmail.com

Adán Pérez-García. Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain; Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. paleontologo@gmail.com

Nuno Pimentel. Instituto Dom Luiz, Universidade de Lisboa, edifício C6, Campo Grande, 1749-016 Lisboa, Portugal. pimentel@fc.ul.pt

Bruno C. Silva. Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. bcsilva.paleo@gmail.com

Francisco Ortega. Grupo de Biología Evolutiva, Facultad de Ciencias, UNED, c/ Senda del Rey, 9, 28040 Madrid, Spain; Laboratório de Paleontologia e Paleoecologia, Sociedade de História Natural, Polígono Industrial do Alto do Ameal, Pav.H02 e H06, 2565-641, Torres Vedras, Portugal. fortega@ccia.uned.es

Keywords: Sauropoda; Upper Jurassic; Lusitanian Basin; Bombarral Sub-basin; Arruda Sub-basin; Turcifal Sub-basin

Mocho, Pedro, Royo-Torres, Rafael, Escaso, Fernando, Malafaia, Elisabete, de Miguel Chaves, Carlos, Narváez, Iván, Pérez-García, Adán, Pimentel, Nuno, Silva, Bruno C., and Ortega, Francisco. 2017. Upper Jurassic sauropod record in the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal): Geographical and lithostratigraphical distribution. Palaeontologia Electronica 20.2.27A: 1-50. https://doi.org/10.26879/662

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2017/1856-portuguese-sauropods

Copyright: © June 2017 Society of Vertebrate Paleontology. This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

INTRODUCTION

The Upper Jurassic sediments of the Lusitanian Basin (Portugal) are known to have yielded abundant fossil vertebrates, in particular dinosaurs, turtles, and crocodyliforms (e.g., Sauvage, 1897-98; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009, 2013). The sauropod fossil record is particularly rich in this basin, and several historical references deal with this clade (e.g., Sauvage, 1897-98; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957).

A systematic revision of the Portuguese taxa of the Late Jurassic was recently performed (for Dinheirosaurus see Mannion et al., 2012; Tschopp et al., 2015; Lusotitan see Mannion et al., 2013; Mocho et al., 2016c; and for Lourinhasaurus, see Mocho et al., 2014b). Several new occurrences have also been reported (Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mateus, 2005; Royo-Torres et al., 2006; Yagüe et al., 2006; Mateus, 2009; Royo-Torres et al., 2009; Ortega et al., 2010; Mannion et al., 2012; Mocho et al., 2012, 2013a, 2013b; Mateus et al., 2014; Mocho et al., 2014a, 2016b, 2017). This new information suggests a more diverse scenario for sauropod fauna during the Late Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin than previously considered, with the identification of a clade previously unidentified in this basin, the non-neosauropod eusauropod group Turiasauria. Royo-Torres et al. (2006) suggested the presence of Turiasauria in the Portuguese Upper Jurassic record, and this hypothesis was subsequently corroborated by the presence of new teeth and postcranial material (Mateus, 2009; Royo-Torres et al., 2009; Ortega et al., 2010; Mocho et al., 2012; Royo-Torres et al., 2014a; Mocho et al., 2016b). Four taxa, so far exclusively, were described in the Upper Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin: the camarasaurid Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas et al., 1998; Mocho et al., 2014b); the diplodocid Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis (Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Mannion et al., 2012; recently referred as Supersaurus lourinhanensis by Tschopp et al., 2015), the basal macronarian and putative brachiosaurid Lusotitan atalaiensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mannion et al., 2013), and the turiasaur Zby atlanticus (Mateus et al., 2014).

The relationships between the Portuguese Upper Jurassic record and North American Morrison Formation dinosaur fauna have been widely discussed. The relatively abundant Portuguese vertebrate fossil record is important in understanding the relationships between North American and European fauna in this period. A combination of shared and exclusive taxa has been used as an argument to justify processes of dispersion and vicariance (Galton, 1980; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Escaso et al., 2007a; Ortega et al., 2013). The relationship of the Portuguese Late Jurassic sauropods to taxa from the North American Upper Jurassic Morrison Fm. (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957) is currently believed to be less close than to other dinosaur groups (Galton, 1980; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Mateus and Antunes, 2003; Escaso et al., 2007a; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2010a, 2010b; Hendrickx and Mateus, 2014; Malafaia et al., 2015) with no species or even genera reported on either side of the Atlantic. Recently, Tschopp et al. (2015) have suggesed the presence of the genus Supersaurus in the Upper Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin.

The present study provides a stratigraphic context for the Portuguese Late Jurassic sauropods from the Lusitanian Basin, considering several geological areas, such as the Bombarral (Bombarral-Alcobaça and Consolação), Turcifal, and Arruda Sub-basins. Many specimens are reported and briefly analysed here for the first time, including several specimens found in Torres Vedras, Lourinhã, Peniche, Caldas da Rainha, and Pombal. Several specimens are under preparation for study, but a preliminary systematic evaluation is presented here. This study aims to provide information about the composition of the sauropod fauna in the Upper Jurassic sequence of the Lusitanian Basin.

Geological Context

The Lusitanian Basin is located in the west region of the Iberian Peninsula, and it is related to the opening of the North Atlantic. This N-S elongated basin has a maximum extension of 225 km x 70 km (Kullberg, 2000). It is part of a set of marginal and peri-North Atlantic basins, which began to be differentiated in the Triassic due to the fragmentation of Pangaea, and evolved during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, when this shore of the Atlantic became a passive margin (Ribeiro et al., 1979; Boillot et al., 1978; Kullberg et al., 2006; Pena dos Reis et al., 2011; Kullberg et al., 2013). The Lusitanian Basin sedimentary sequence was deposited from the Middle Triassic (?Ladinian - Carnian) (Rocha et al., 1996) to the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) (Rey, 1999) (Figure 1). The evolution of the basin took place mainly in an extensional tectonic context (Kullberg et al., 2006) and in some regions, this sedimentary sequence reaches a thickness of 5000 m (Ribeiro et al., 1979). From the Late Cretaceous onwards, alpine compressive episodes led to the cessation of sedimentation and ultimately the inversion of the basin, with predominant up-lift and the exposure of most of its Mesozoic sequence.

The Lusitanian Basin is located in the west region of the Iberian Peninsula, and it is related to the opening of the North Atlantic. This N-S elongated basin has a maximum extension of 225 km x 70 km (Kullberg, 2000). It is part of a set of marginal and peri-North Atlantic basins, which began to be differentiated in the Triassic due to the fragmentation of Pangaea, and evolved during the Jurassic and Cretaceous, when this shore of the Atlantic became a passive margin (Ribeiro et al., 1979; Boillot et al., 1978; Kullberg et al., 2006; Pena dos Reis et al., 2011; Kullberg et al., 2013). The Lusitanian Basin sedimentary sequence was deposited from the Middle Triassic (?Ladinian - Carnian) (Rocha et al., 1996) to the Late Cretaceous (Turonian) (Rey, 1999) (Figure 1). The evolution of the basin took place mainly in an extensional tectonic context (Kullberg et al., 2006) and in some regions, this sedimentary sequence reaches a thickness of 5000 m (Ribeiro et al., 1979). From the Late Cretaceous onwards, alpine compressive episodes led to the cessation of sedimentation and ultimately the inversion of the basin, with predominant up-lift and the exposure of most of its Mesozoic sequence.

The Upper Jurassic sequence is the focus of this study, and represents the main subsidence phase of the basin, with an accumulation of over 3 km in sedimentary thickness, in a short period, at its main depocenters (Pena dos Reis et al., 1996, 2000). It ranges from the middle Oxfordian to the boundary with the Lower Cretaceous (Schneider et al., 2009). The Upper Jurassic sedimentary sequence represents a third rifting episode (Rasmussen et al., 1998; Kullberg et al., 2006), marked by intense subsidence and an internal differentiation in three main sectors (Rocha and Soares, 1984). The northern sector extends from Coimbra to the Nazaré fault and is characterized by lower subsidence; the central sector extends from this main tectonic line to the Lisboa area and presents the maximum subsidence; and the southern sector extends from Lisboa to the alpine Arrabida chain, with the lowest subsidence. This episode of rifting was marked by an important sedimentary input into the whole basin, which progressively filled the basin (Guéry, 1984; Hill, 1988; Wilson, 1988; Pena dos Reis et al., 2000; Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013). From the lower Kimmeridgian up to the top of the Upper Jurassic, the sedimentary sequence was dominated by abundant siliciclastic inputs, with a mainly continental and transitional signature (e.g., Hill, 1988; Manuppella et al., 1999; Kullberg et al., 2006). As accommodation space decreased, coastal environments became shallower and siliciclastics prograded into the basin, with the gradual development of fluvial environments, giving origin to a predominantly braided fluvial sedimentation in Berriasian times (Torres Vedras Group). Late Jurassic paleogeographic reconstructions point to a narrow trough developing from NE proximal areas to SW distal areas, with both longitudinal axial drainage and lateral inputs from the eastern and western basement borders (Pena dos Reis et al., 2011). Palaeoenvironments grade from proximal braided fluvial deposits to distal fine-grained meandering, and even deltaic to coastal deposits. Siliciclastics are clearly predominant, but some minor carbonate and shell-rich intercalations may be found, particularly in distal areas (Pena dos Reis et al., 2011).

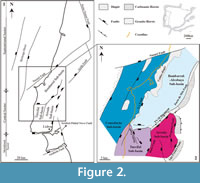

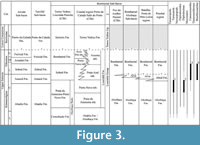

The central sector corresponds mainly to distal fluvio-deltaic and coastal environments, which produced the richest fossil record of terrestrial vertebrates in the Lusitanian Basin (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009). No sauropod osteological remains have yet been identified in the Upper Jurassic of the southern or northern sectors of the Lusitanian Basin. The Central Sector of the Lusitanian Basin has been divided into three Upper Jurassic sub-basins, the Turcifal, Arruda, and Bombarral (Figure 2.1), based on isopachs and facies distribution (Pena dos Reis et al., 1996, 2000). The stratigraphy of the Upper Jurassic sequence of the Lusitanian Basin is complex, due the profuse lateral heterogeneity and the proposal of several and different stratigraphic approaches (e.g., Hill, 1988; Leinfelder, 1993; Manuppella et al., 1999; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009; Martinius and Gowland, 2011; Taylor et al., 2014). Figure 3 presents the stratigraphic correlations between the nomenclature proposed for the areas considered in this manuscript: i) Turcifal Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Pereda-Suberbiola et al., 2005; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009); ii) Arruda Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006); iii) Consolação Sub-basin areas: Torres Vedras-Lourinhã-Peniche (stratigraphy based on Manuppella et al., 1999), Foz do Arelho-Nazaré coastal sector (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Azerêdo et al., 2010); iv) Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Azerêdo et al., 2010); v) Batalha-Leiria region (stratigraphy based on Manuppella et al., 2000; Kullberg et al. 2006; Escaso et al., 2007a), and vi)

The central sector corresponds mainly to distal fluvio-deltaic and coastal environments, which produced the richest fossil record of terrestrial vertebrates in the Lusitanian Basin (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009). No sauropod osteological remains have yet been identified in the Upper Jurassic of the southern or northern sectors of the Lusitanian Basin. The Central Sector of the Lusitanian Basin has been divided into three Upper Jurassic sub-basins, the Turcifal, Arruda, and Bombarral (Figure 2.1), based on isopachs and facies distribution (Pena dos Reis et al., 1996, 2000). The stratigraphy of the Upper Jurassic sequence of the Lusitanian Basin is complex, due the profuse lateral heterogeneity and the proposal of several and different stratigraphic approaches (e.g., Hill, 1988; Leinfelder, 1993; Manuppella et al., 1999; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009; Martinius and Gowland, 2011; Taylor et al., 2014). Figure 3 presents the stratigraphic correlations between the nomenclature proposed for the areas considered in this manuscript: i) Turcifal Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Pereda-Suberbiola et al., 2005; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009); ii) Arruda Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006); iii) Consolação Sub-basin areas: Torres Vedras-Lourinhã-Peniche (stratigraphy based on Manuppella et al., 1999), Foz do Arelho-Nazaré coastal sector (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Azerêdo et al., 2010); iv) Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Azerêdo et al., 2010); v) Batalha-Leiria region (stratigraphy based on Manuppella et al., 2000; Kullberg et al. 2006; Escaso et al., 2007a), and vi) Pombal region (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Malafaia et al., 2010a). This nomenclature will be used in the present study. The term Lourinhã Formation was proposed by Hill (1988) and has been widely used in vertebrate paleontological literature. This formation was defined on the coastal sections south of São Bernardino (Peniche) to Porto da Calada (Mafra). This formation seems to be coincident with the upper part of the Alcobaça, Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo, Sobral, Freixial, and Bombarral Formations referenced by other authors, including the Portuguese Geological Surveys (e.g., Manuppella et al., 1999). The use of this unit outside the area corresponding to the Consolação Sub-basin of Taylor et al. (2014) is not completely established in literature (e.g., Hill, 1988; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009; Ribeiro and Mateus, 2012; Kullberg et al., 2013; Mateus et al., 2013). Yagüe et al. (2006) therefore incorporate the entire Alcobaça Formation and the previously defined Lourinhã Formation into a new lithostratigraphic unit, the Lourinhã Group. The stratigraphic proposals of Hill (1988) and Yaguë et al. (2006) are also presented in the Figure 3.

Pombal region (stratigraphy based on Kullberg et al., 2006; Malafaia et al., 2010a). This nomenclature will be used in the present study. The term Lourinhã Formation was proposed by Hill (1988) and has been widely used in vertebrate paleontological literature. This formation was defined on the coastal sections south of São Bernardino (Peniche) to Porto da Calada (Mafra). This formation seems to be coincident with the upper part of the Alcobaça, Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo, Sobral, Freixial, and Bombarral Formations referenced by other authors, including the Portuguese Geological Surveys (e.g., Manuppella et al., 1999). The use of this unit outside the area corresponding to the Consolação Sub-basin of Taylor et al. (2014) is not completely established in literature (e.g., Hill, 1988; Kullberg et al., 2006; Schneider et al., 2009; Ribeiro and Mateus, 2012; Kullberg et al., 2013; Mateus et al., 2013). Yagüe et al. (2006) therefore incorporate the entire Alcobaça Formation and the previously defined Lourinhã Formation into a new lithostratigraphic unit, the Lourinhã Group. The stratigraphic proposals of Hill (1988) and Yaguë et al. (2006) are also presented in the Figure 3.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

The studied material is mainly deposited in Portuguese institutions, excluding one specimen found in the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Paris, France) (see list in Appendix 1). All the specimens are described and discussed based on direct observations. We use “Romerian” terms for anatomical structures for the structures (e.g., “centrum”) and their orientation (e.g., “anterior”) (Wilson, 2006). This study applies the landmark-based terminology of Wilson (1999, 2012) and Wilson et al. (2011) for vertebral laminae and fossae.

Anatomical Abbreviations

aacet, articulation for the acetabulum; acc, acromial crest; acet, acetabulum; ant. spdl, anterior spinodiapophyseal lamina; asp, ascending process; aspa, articular surface for the ascending process; awf, apical wear facet; br, bridge; cc, cnemial crest; cml, camellae; cpol, centropostzygapophyseal lamina; cr, caudal rib; cwf, carina wear facet; di, diapophyses; dpc, deltopectoral crest; ec, epicondyle; f, fossa; fic, fibular condyle; ft, fourth trochanter; gl, glenoid; gr, groove; ibi, incipient bifurcation; ilped, iliac peduncle; isped, ischiatic peduncle; lag, labial groove; lb, lateral bulge; lf, lingual facets; lic, lingual crest; lt, lateral trochanter; hy, hyposphene; lat.spol, lateral spinopostzygapophyseal lamina; of, obturator foramen; pafc, posterior astragalar fossa crest; paf, posterior astragalar fossa; pcdl, posterior centrodiapophyseal lamina; pcpl, posterior centroparapophyseal lamina; pfr, pneumatic foramen; podl, postzygodiapophyseal lamina; posl, postspinal lamina; post. spdl, posterior spinodiapophyseal lamina; poz, postzygapophyses; prsl, prespinal lamina; prdl, prezygodiapophyseal lamina; prz, prezygapophyses; spof, spinopostzygapophyseal fossa; spol, spinopostzygapophyseal lamina; sprf, spinoprezygapophyseal fossa; sprl, spinoprezygapophyseal lamina; tap, triangular aliform process; tb, tuberosity; tia, tibial articular surface; tic, tibial condyle; vh, ventral hollow; vlc, ventrolateral crest; vpr, ventral process.

Institutional Abbreviations

MG, Museu Geológico (Lisboa, Portugal); ML, Museu da Lourinhã (Lourinhã, Portugal); MMPM, Museu Municipal de Porto de Mós (Porto de Mós, Portugal); MMB, Museu Municipal do Bombarral (Bombarral, Portugal); MMLT, Museu Municipal Leonel Trindade (Torres Vedras, Portugal); MNHN, Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle (Paris, France); MNHNUL, Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa, Portugal); SHN, Sociedade de História Natural, plus JJS for the José Joaquim dos Santos collection (Torres Vedras, Portugal).

UPPER JURASSIC SAUROPOD RECORD OF THE LUSITANIAN BASIN

The sauropod record will be presented as following a palaeogeographic distribution, corresponding mainly to the Upper Jurassic sub-basins of the central sector (Figure 2), however, it must be noted that these sub-basins have been defined based on, essentially, geodynamic features, namely the existence of three depocentres separated by main tectonic fault lines and by less subsident areas. These areas could eventually represent paleotopographic highs, which may account for some palaeogeographic differences between sub-basins. Sub-basins could therefore represent low-lands where water, vegetation, and vertebrates would have had better conditions in which to develop and accumulate. If so, these areas might represent different contemporaneous communities, occupying slightly different habitats or palaeoenvironments, more or less open to coastal influences or connections.

Bombarral Sub-basin

The Bombarral Sub-basin is the widest Upper Jurassic sub-basin of the central sector of the Lusitanian Basin. It is also the richest area with respect to fossil sites with vertebrates (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Ortega et al., 2009). This basin is delimited in the north by the Nazaré Fault and in the east and south by the Porto-Tomar, Arrife, and Torres-Vedras-Montejunto Faults (Kullberg, 2000; Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013; Figure 2.1). The Torres Vedras-Montejunto Fault separates the Bombarral Sub-basin from the half-graben Turcifal and Arruda Sub-basins (Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013). Taylor et al. (2014) established two new sub-basins replacing the Bombarral Sub-Basin, called the Consolação and Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basins (Figure 2.2).

The Consolação Sub-basin is located on the west of the Lourinhã Fault and the Caldas Diapir, and is bounded in the north by the Nazaré Fault (Figure 2.2). This sub-basin includes the Upper Jurassic coastal sector from Praia da Consolação (Peniche) to Santa Cruz (Torres Vedras) and some Upper Jurassic cliffs north of Peniche, and from Nazaré to Foz do Arelho. The remaining area of the previously defined Bombarral Sub-basin, and that on the east of the Lourinhã Fault and the Caldas Diapir, is now included in the Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin (Figure 2.2; Taylor et al., 2014). We follow the sub-division of the Lusitanian Basin Central Sector proposed by Kullberg et al. (2006, 2013) always referring to the correspondent nomenclature proposed by Taylor et al. (2014).

The presence of several dinosaur remains in the Bombarral Sub-basin has been reported since the end of the nineteenth century (e.g., Sauvage, 1897-98; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003), most notably those from Upper Jurassic sediments outcropping in the Lourinhã, Peniche, and Pombal municipalities (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Antunes and Mateus, 2003). Several occurrences of non-sauropod dinosaurs (theropods, ornithopods, and thyreophorans) were also reported. Theropod fauna are comprised of basal forms representing Ceratosauria (Ceratosaurus sp.), Megalosauroidea (Torvosaurus gurneyi), and Allosauroidea, such as Allosaurus and Lourinhanosaurus antunesi (e.g., Dantas, 1987; Mateus et al., 1997; Mateus, 1998; Dantas et al., 1999; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Mateus and Antunes, 2000a, 2000b; Rauhut, 2000; Mateus, 2005, 2006; Mateus et al., 2006; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2008, 2010a, 2010b; Hendrickx and Mateus, 2012, 2014; Malafaia et al., 2015, 2016, 2017). Derived theropods are also represented by mostly isolated specimens related to the clade Coelurosauria, including the basal tyrannosauroid Aviatyrannis, indeterminate dromeosaurids, and several teeth attributed to cf. Archaeopteryx (Weigert, 1995; Zinke, 1998; Zinke and Rauhut, 1994; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mateus, 2005; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2010a, 2014). The most important Bombarral Sub-basin theropod fossil sites are reported from Andrés in Pombal (Dantas et al., 1999; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2010a), Paimogo in Lourinhã (Dantas, 1987; Mateus et al., 1997), Vale de Pombas-Praia Vermelha coastal cliffs in Lourinhã-Peniche (Mateus, 2005; Hendrickx and Mateus, 2014), and the Guimarota mine in Leiria (Zinke, 1998; Rauhut, 2000, 2003; Rauhut and Fechner, 2005).

The Bombarral Sub-basin is also rich in ornithischian remains, with the presence of at least four ornithopod and three thyreophoran forms. Several historical specimens were referred to the genus Omosaurus (Zbyszewski, 1946; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), but some part of this material, as well as new specimens, were later assigned to the genus Dacentrurus (e.g., Galton, 1991; Maidment et al., 2008; Ortega et al., 2009). This genus is also present in the Spanish Villar del Arzobisbo Formation (Kimmeridgian-Berriasian in age), as the only known shared dinosaur genus between these territories for the Late Jurassic (Cobos et al., 2010; Cobos and Gascó, 2013). More recently, two other stegosaurian forms were identified in the Upper Jurassic levels of the Bombarral Sub-basin. Escaso et al. (2007a) referred a partial individual found in Casal Novo (Alcobaça Fm., Leiria) to the North American Morrison Fm. genus Stegosaurus, proposing a Late Jurassic contact for the Iberian and North American fauna. Mateus et al. (2009) established a new stegosaurian taxon, Miragaia longicollum, a form closely related to Dacentrurus. Cobos et al. (2010) proposed Miragaia as synonymous with of Dacentrurus, a hypothesis followed by Escaso (2014) and Maidment et al. (2015).

The Upper Jurassic ornithopod record of the Bombarral Sub-basin is represented by the dryosaurid Eousdryosaurus (Escaso et al., 2014) and two styracosternans: Camptosaurus (=Uteodon) aphanoecetes, previously identified in the Morrison Formation (Escaso et al., 2010a, 2010b) and the exclusive Portuguese form Draconyx loureiroi (Mateus and Antunes, 2001). Another ornithopod, based on teeth from the Guimarota mine, was described as Phyllodon henkeli (Thulborn, 1973). Rauhut (2001) referred some additional teeth as well as three partial dentaries to this taxon.

Other vertebrate groups have been reported, such as fishes (Sauvage, 1897-98; Kriwet, 2000; Balbino, 2003), amphibians (Wiechmann, 2000), turtles (Sauvage, 1897-98; Bräm, 1973; Antunes et al., 1988; Gassner, 2000; Pérez-García and Ortega, 2011; Pérez-García, 2015); sphenodonts (Ortega et al., 2006; Malafaia et al., 2010a), squamates (Seiffert, 1973; Broschinski, 2000; Caldwell et al., 2015), pterosaurs (Dantas, 1987; Wiechmann and Gloy, 2000), crocodyliforms (Sauvage, 1897-98; Krebs and Schwarz, 2000; Schwarz and Fechner, 2004; Schwarz and Salisbury, 2005; Tennant and Mannion, 2014; Russo et al., 2017), mammals (e.g., Hahn, 1971; Krusat, 1980; Hahn and Hahn, 2000; Krebs, 2000; Martin, 2000; Martin and Nowotny, 2000; Martin, 2005), and possible plesiosaurs (Castanhinha and Mateus, 2007).

The sauropods are well represented in this sub-basin, being recognised in many fossil sites, with numerous occurrences (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mateus, 2005; Mocho et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014a, 2016a, 2017). We will report the sauropod record in the following different areas of the Bombarral Sub-basin: i) northern region of Maciço Calcário Estremenho; ii) coastal sector from Foz do Arelho to Nazaré; iii) Alcobaça, Bombarral and A-dos-Cunhados; iv) North Peniche; and v) Praia da Consolação-Lourinhã-Torres Vedras coastal sector. This subdivision seems useful considering the profuse lateral lithological heterogeneity and the proposal of several stratigraphic approaches for each area within this sub-basin, and also to provide a more accurate overview of the abundant sauropod fossil record in the Bombarral Sub-basin.

Northern region of Maciço Calcário Estremenho (Figure 4, Figure 5). The region north of the Maciço Calcário Estremenho (MCE) is rich in transitional to continental Upper Jurassic deposits (Camarate França and Zbyszewski, 1963; Teixeira et al., 1966; Manuppella et al., 2000), including several fossil sites in the Pombal, Leiria, Batalha, and Porto-de-Mós municipalities. Several important vertebrate sites are identified in this area, notably the Guimarota mine (Leiria), and Andrés (Pombal) and Casal Novo (Batalha) quarries (e.g., Peréz-Moreno et al., 1999; Rauhut, 2000; Escaso et al., 2007a; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2010a). The sauropod record is relatively poor in this sector of the Bombarral Sub-basin and is mainly based on incomplete specimens (Figure 5). Samples come from sediments in the Alcobaça and Bombarral Formations (Figure 4.2-3, Figure 5), and there is published and unpublished material (e.g., Malafaia et al., 2010a; Mocho et al., 2016a, 2017). The Alcobaça Fm. is interpreted as having been deposited in marine environments, transiting to fluvio-lacustrine deposits at the top of the formation. In this area, the Alcobaça Fm. is lower Kimmeridgian-lower Tithonian in age, being considered as laterally correlated with the marine Abadia Fm., present in the south of the Lusitanian Basin Central Sector (Manuppella et al., 2000). Some important fossil sites found in the Alcobaça Fm. correspond to fluvial (Escaso et al., 2007a) and lagoonal deposits (Schudack, 2000). The Bombarral Fm. is composed of fluvio-lacustrine deposits, dated to the late Kimmeridgian-Tithonian (Manuppella et al., 2000).

Northern region of Maciço Calcário Estremenho (Figure 4, Figure 5). The region north of the Maciço Calcário Estremenho (MCE) is rich in transitional to continental Upper Jurassic deposits (Camarate França and Zbyszewski, 1963; Teixeira et al., 1966; Manuppella et al., 2000), including several fossil sites in the Pombal, Leiria, Batalha, and Porto-de-Mós municipalities. Several important vertebrate sites are identified in this area, notably the Guimarota mine (Leiria), and Andrés (Pombal) and Casal Novo (Batalha) quarries (e.g., Peréz-Moreno et al., 1999; Rauhut, 2000; Escaso et al., 2007a; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2010a). The sauropod record is relatively poor in this sector of the Bombarral Sub-basin and is mainly based on incomplete specimens (Figure 5). Samples come from sediments in the Alcobaça and Bombarral Formations (Figure 4.2-3, Figure 5), and there is published and unpublished material (e.g., Malafaia et al., 2010a; Mocho et al., 2016a, 2017). The Alcobaça Fm. is interpreted as having been deposited in marine environments, transiting to fluvio-lacustrine deposits at the top of the formation. In this area, the Alcobaça Fm. is lower Kimmeridgian-lower Tithonian in age, being considered as laterally correlated with the marine Abadia Fm., present in the south of the Lusitanian Basin Central Sector (Manuppella et al., 2000). Some important fossil sites found in the Alcobaça Fm. correspond to fluvial (Escaso et al., 2007a) and lagoonal deposits (Schudack, 2000). The Bombarral Fm. is composed of fluvio-lacustrine deposits, dated to the late Kimmeridgian-Tithonian (Manuppella et al., 2000).

Near Pombal, sauropod fossils were only identified in the sediments of the Bombarral Formation. A great accumulation of fossils representing a relatively diverse vertebrate fauna was identified at the Andrés locality in the Tithonian levels of the Bombarral Fm. (Dantas et al., 1999; Pérez-Moreno et al., 1999; Malafaia et al., 2007, 2009a, 2010a). Several teeth and postcranial material assigned to Sauropoda were collected at this fossil site (Figure 5.5). A preliminary analysis of the teeth allowed the recognition of four different morphotypes: spatulate, heart-, compressed cone-chisel-, and peg-shaped, which led Malafaia et al. (2010a) to suggest the presence of forms related to Diplodocoidea, Turiasauria, and Titanosauriformes. However, the presence of compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth in Europasaurus (Sander et al., 2006), which was recently considered as a non-titanosauriform macronarian (Carballido and Sander, 2014), might indicate that this tooth morphology was already present in non-titanosauriform macronarians. More teeth and postcranial elements from the Andrés site are being prepared (EM, personal commun., 2015).

Also in the Pombal area, a middle/posterior caudal vertebra (Figure 5.4, MG 4811) was found in Albergaria dos Doze (Pombal), probably from the Bombarral Formation (Figure 4.2). Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) attributed this element to the theropod Megalosaurus pombali. Subsequently, Mateus (2005) considered this vertebra to belong to an indeterminate theropod. This vertebra probably corresponds to an indeterminate sauropod based on its general morphology, transversely convex ventral face and an anteroposteriorly short neural arch. A middle or posterior dorsal neural spine was also found in this area, near Vermoil (Bombarral Fm., Figure 5.8-9, MNHN.unnumbered). This neural spine probably represents a eusauropod due the presence of a transversely expanded neural spine and a well-defined prespinal lamina (Mocho et al., 2017). More recently, a new fossil site containing a partial sauropod skeleton (dorsal vertebrae and ribs) was found in Pombal (Figure 5.14) during fieldwork carried out by the Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa, Portugal).

Also in the Pombal area, a middle/posterior caudal vertebra (Figure 5.4, MG 4811) was found in Albergaria dos Doze (Pombal), probably from the Bombarral Formation (Figure 4.2). Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) attributed this element to the theropod Megalosaurus pombali. Subsequently, Mateus (2005) considered this vertebra to belong to an indeterminate theropod. This vertebra probably corresponds to an indeterminate sauropod based on its general morphology, transversely convex ventral face and an anteroposteriorly short neural arch. A middle or posterior dorsal neural spine was also found in this area, near Vermoil (Bombarral Fm., Figure 5.8-9, MNHN.unnumbered). This neural spine probably represents a eusauropod due the presence of a transversely expanded neural spine and a well-defined prespinal lamina (Mocho et al., 2017). More recently, a new fossil site containing a partial sauropod skeleton (dorsal vertebrae and ribs) was found in Pombal (Figure 5.14) during fieldwork carried out by the Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa, Portugal).

A large area with Upper Jurassic continental sediments from the Alcobaça and Bombarral Formations is located across the localities of Batalha, Vila Nova de Ourém, Leiria, and Porto-de-Mós. In the Alcobaça Fm., one of the most important accumulations was found in the Guimarota mine, in Leiria (e.g., Rauhut, 2000). The Guimarota fossil record is relatively poor in sauropod remains, but some small teeth referred to Brachiosauridae (Rauhut, 2000), or to cf. Lusotitan atalaiensis (Mateus, 2005) were found (Figure 5.2-3). Sauvage (1897-98) and Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) also reported some localities with dinosaur remains near Vila Nova de Ourém and Porto de Mós (probably from the Alcobaça Fm.). Two teeth, one had a heart-shaped morphology probably referrable to Turiasauria (Figure 5.6-7, MG 16; Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b) and other had a compressed cone-chisel-shaped morphology (Figure 5.1, MG 8779) common in Titanosauriformes, but also found in the basal macronarian Europasaurus (Sander et al., 2006; Carballido and Sander, 2014). A posterior caudal vertebra (MMPM.P/554) from an indeterminate sauropod was also found in Fonte do Oleiro (Alcobaça Fm.), south of the town of Porto de Mós (Mocho et al., 2017).

Mocho et al. (2017) described some sauropod specimens found close to the town of Batalha, and they are deposited in the collections of the Museu Geológico and Museu Municipal de Porto-de-Mós, including: i) a partial dorsal centrum and a partial caudal series collected in Abadia (Figure 5.10-13, MG 4974), and ii) a set of sauropod bones including dorsal and caudal vertebrae and a fragmentary ischium from Batalha, which might represent a member of Diplodocinae (Figure 5.15-18, MG 30389). The stratigraphic and geographic context of these specimens is not clear, and they might pertain to the Alcobaça Fm. or to the Bombarral Fm.

The presence of non-neosauropod eusauropods, probably turiasaurs, indeterminate diplodocoids (including members of Diplodocinae), and macronarians, was identified in the area located in the north of the Maciço Calcário Estremenho (Figure 4.1).

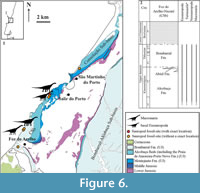

Coastal sector from Foz do Arelho to Nazaré (Figure 6, Figure 7). An extensive sector with Upper Jurassic sediments in the Bombarral (following Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013; Azerêdo et al., 2010), or Consolação Sub-basin (following Taylor et al., 2014), crops westwards out of the Caldas Diapir (Figure 6.1). This sequence extends from the coastal cliffs of Foz do Arelho to Nazaré (e.g., Hill, 1988; Kullberg et al., 2006), and includes sediments of the Alcobaça (Kimmeridgian to basal Tithonian) and Bombarral (Tithonian) Formations (Figure 6.2) (Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013; Schneider et al., 2009; Azerêdo et al., 2010). Both formations are particularly rich in fossil vertebrate finds. One of the most important fossil sites is the historical site in Murteiras (Caldas da Rainha) (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), due the presence of several specimens referred to Dacentrurus (Galton, 1991; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Maidment et al., 2008; Escaso, 2014). No sauropod remains were reported there, however (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957).

Coastal sector from Foz do Arelho to Nazaré (Figure 6, Figure 7). An extensive sector with Upper Jurassic sediments in the Bombarral (following Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013; Azerêdo et al., 2010), or Consolação Sub-basin (following Taylor et al., 2014), crops westwards out of the Caldas Diapir (Figure 6.1). This sequence extends from the coastal cliffs of Foz do Arelho to Nazaré (e.g., Hill, 1988; Kullberg et al., 2006), and includes sediments of the Alcobaça (Kimmeridgian to basal Tithonian) and Bombarral (Tithonian) Formations (Figure 6.2) (Kullberg et al., 2006, 2013; Schneider et al., 2009; Azerêdo et al., 2010). Both formations are particularly rich in fossil vertebrate finds. One of the most important fossil sites is the historical site in Murteiras (Caldas da Rainha) (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), due the presence of several specimens referred to Dacentrurus (Galton, 1991; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Maidment et al., 2008; Escaso, 2014). No sauropod remains were reported there, however (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957).

Sauropod remains collected in the Alcobaça Formation (following Camarate França and Zbyszewski, 1963; Azerêdo et al., 2010), outcropping in this sector of the Bombarral Sub-basin, (Figure 6.1) include axial elements (Figure 7.1-3, MMPM.P/551) found close to São Martinho do Porto (Mocho et al., 2017), and some unpublished caudal vertebrae and pelvic fragments (Figure 7.18, SHN 537) found in Salir do Porto. An anterior dorsal neural spine (Figure 7.8, MG 4920; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957) of an indeterminate eusauropod from Foz do Arelho (Caldas da Rainha) was collected from sediments of the Bombarral Fm.

Several teeth were collected in this coastal area, corresponding to different morphotypes: i) heart-shaped teeth (Figure 7.4-7, 7.11-15, 7.16-17), tentatively referred to Turiasauria (see Royo-Torres and Upchurch, 2012; Royo-Torres et al., 2009; Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b); ii) spatulate teeth (Figure 7.9-10; unpublished material housed in MG and SHN) referred to an indeterminate eusauropod (probably a macronarian); and iii) compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (unpublished material housed in the SHN), referred to Macronaria. The first of these morphotypes is the most abundant in this coastal sector.

Several teeth were collected in this coastal area, corresponding to different morphotypes: i) heart-shaped teeth (Figure 7.4-7, 7.11-15, 7.16-17), tentatively referred to Turiasauria (see Royo-Torres and Upchurch, 2012; Royo-Torres et al., 2009; Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b); ii) spatulate teeth (Figure 7.9-10; unpublished material housed in MG and SHN) referred to an indeterminate eusauropod (probably a macronarian); and iii) compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (unpublished material housed in the SHN), referred to Macronaria. The first of these morphotypes is the most abundant in this coastal sector.

The known and the new occurrences put in evindece a relatively high potential for future discoveries in this area, However, the so far published (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b, 2017) and unpublished material of sauropods only allows identification of indeterminate sauropods and eusauropods, possibly members of Turiasauria, and indeterminate macronarians. The presence of several compressed cone-chisel teeth in the sedimentary sequence suggests the presence of macronarian forms within the clade formed by Europasaurus + Titanosauriformes (Figure 6.2).

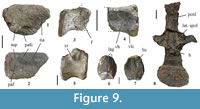

Alcobaça, Bombarral, and A-dos-Cunhados (Figure 8, Figure 9). A large area with Upper Jurassic sediments, included within the Bombarral Sub-basin, is found east of the Lourinhã Fault and the Caldas Diapir, defined as the Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin by Taylor et al. (2014) (Figure 8.1). This area is poorly prospected when compared with other areas, such as the coastal sector from Praia da Consolação to Torres Vedras. In fact, this area is generally covered by soil with natural vegetation or agriculture, resulting in only a few outcrops that could produce vertebrate fossils. The most important localities are Moita dos Ferreiros (Mateus, 2005; Mannion et al., 2012) and Miragaia, where the type material for Miragaia longicollum was found (Mateus et al., 2009). Sauropod remains are scarce in this area (Figure 8.1), although there are also some specimens housed in private collections (e.g., Mateus, 2005; pers. observ., PM), such as a partial tail of an indeterminate sauropod, collected near the town of Bombarral.

Alcobaça, Bombarral, and A-dos-Cunhados (Figure 8, Figure 9). A large area with Upper Jurassic sediments, included within the Bombarral Sub-basin, is found east of the Lourinhã Fault and the Caldas Diapir, defined as the Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin by Taylor et al. (2014) (Figure 8.1). This area is poorly prospected when compared with other areas, such as the coastal sector from Praia da Consolação to Torres Vedras. In fact, this area is generally covered by soil with natural vegetation or agriculture, resulting in only a few outcrops that could produce vertebrate fossils. The most important localities are Moita dos Ferreiros (Mateus, 2005; Mannion et al., 2012) and Miragaia, where the type material for Miragaia longicollum was found (Mateus et al., 2009). Sauropod remains are scarce in this area (Figure 8.1), although there are also some specimens housed in private collections (e.g., Mateus, 2005; pers. observ., PM), such as a partial tail of an indeterminate sauropod, collected near the town of Bombarral.

Some older occurrences from the Alcobaça Formation were found in the Alcobaça, Bombarral, and A-dos-Cunhados regions (Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin) and referred to Sauropoda (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957): i) an heart-shaped tooth (Figure 9.6-7) from Fervença (Sauvage, 1897-98; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), tentatively referred to an indeterminate eusauropod probably related to Turiasauria (Mocho et al., 2016b); and ii) a posterior caudal vertebra from Chiqueda de Cima (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), representing an indeterminate sauropod. Some elements were found in the Bombarral Fm.: i) an anterior caudal vertebra (Figure 9.5, MG 4804) of an indeterminate eusauropod from Salir de Matos; ii) a middle caudal vertebrae (Figure 9.3-4, MG 4819, 4821, 4826) of an indeterminate diplodocine from São Gregório da Fanadia; and iii) a large left astragalus (Figure 9.1-2, MMPM.P/75) attributed to an indeterminate eusauropod was found in Imaginário (Caldas da Rainha) (Mocho et al., 2016a, 2017).

An incomplete skeleton composed of axial elements (cervical and dorsal vertebrae; Figure 9.8, ML 418), considered as aff. Dinheirosaurus (Antunes and Mateus, 2003) and Apatosaurus sp. (Mateus, 2005), was found close to Moita dos Ferreiros (Lourinhã, Bombarral Formation). These elements are poorly preserved. Mannion et al. (2012) distinguished this specimen from Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis and suggested that it might represent a second diplodocid taxon from the Upper Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin. Tschopp et al. (2015) suggested that it represents an indeterminate diplodocine different from Dinheirosaurus. The full preparation of the dorsal vertebrae of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis will be important to test this hypothesis.

An incomplete skeleton composed of axial elements (cervical and dorsal vertebrae; Figure 9.8, ML 418), considered as aff. Dinheirosaurus (Antunes and Mateus, 2003) and Apatosaurus sp. (Mateus, 2005), was found close to Moita dos Ferreiros (Lourinhã, Bombarral Formation). These elements are poorly preserved. Mannion et al. (2012) distinguished this specimen from Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis and suggested that it might represent a second diplodocid taxon from the Upper Jurassic of the Lusitanian Basin. Tschopp et al. (2015) suggested that it represents an indeterminate diplodocine different from Dinheirosaurus. The full preparation of the dorsal vertebrae of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis will be important to test this hypothesis.

In summary, the dinosaur fauna in the Alcobaça, Bombarral and A-dos-Cunhados area are poorly understood. The recorded sauropod fauna in this area is composed of indeterminate taxa, and indeterminate eusauropods (some tentatively assigned to Turiasauria), and indeterminate diplodocines. One of the diplodocine specimens (ML 418) might represent a diplodocine different from Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis (Mannion et al., 2012; Tschopp et al., 2015).

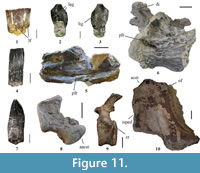

North Peniche (Figure 10, Figure 11). An Upper Jurassic section, including the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo and Bombarral Formations, crops out north of the town of Peniche (Manuppella et al., 1999; Azerêdo et al., 2010) (Figure 10). Some stratigraphic approaches have suggested the presence of the Sobral Fm. along this sequence (e.g., Hill, 1988; Martinius and Gowland, 2011) (Figure 10.2). This section is not very large (its maximum length is about 2 km), but it is rich in fossil sites, some of them known since the first half of the twentieth century. The most important dinosaur site is located in Pedras Muitas (Peniche) where remains of sauropods and stegosaurs have been collected (Zbyszewski, 1946; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957). Their precise location is not clear. According to the available stratigraphic information (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Camarate França et al., 1960; Hill, 1988; Bernardes, 1992; Schneider et al., 2009; Azerêdo et al., 2010; Martinius and Gowland, 2011; Taylor et al., 2014), these elements probably came from sediments of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Fm. Some partial middle and posterior sauropod cervical vertebrae (MG 4915, 4916, 4917 and 4919) were found in Pedras Muitas. These remains include a misidentified cervical vertebra, previously considered part of an Omosaurus individual (Zbyszewski, 1946, pl. I, figure 1). This specimen includes middle and posterior cervical vertebrae (Figure 11.5-6), which have been subject to a systematic revision and might represent a neosauropod form due the presence of polycamerate cervical vertebrae with bifurcated neural spine.

North Peniche (Figure 10, Figure 11). An Upper Jurassic section, including the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo and Bombarral Formations, crops out north of the town of Peniche (Manuppella et al., 1999; Azerêdo et al., 2010) (Figure 10). Some stratigraphic approaches have suggested the presence of the Sobral Fm. along this sequence (e.g., Hill, 1988; Martinius and Gowland, 2011) (Figure 10.2). This section is not very large (its maximum length is about 2 km), but it is rich in fossil sites, some of them known since the first half of the twentieth century. The most important dinosaur site is located in Pedras Muitas (Peniche) where remains of sauropods and stegosaurs have been collected (Zbyszewski, 1946; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957). Their precise location is not clear. According to the available stratigraphic information (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Camarate França et al., 1960; Hill, 1988; Bernardes, 1992; Schneider et al., 2009; Azerêdo et al., 2010; Martinius and Gowland, 2011; Taylor et al., 2014), these elements probably came from sediments of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Fm. Some partial middle and posterior sauropod cervical vertebrae (MG 4915, 4916, 4917 and 4919) were found in Pedras Muitas. These remains include a misidentified cervical vertebra, previously considered part of an Omosaurus individual (Zbyszewski, 1946, pl. I, figure 1). This specimen includes middle and posterior cervical vertebrae (Figure 11.5-6), which have been subject to a systematic revision and might represent a neosauropod form due the presence of polycamerate cervical vertebrae with bifurcated neural spine.

Other sauropod remains were also identified to the north of Peniche. Most of these specimens are deposited in the collections of the MG, ML and SHN. A currently unpublished, partial spatulate tooth (Figure 11.1, MG 8783), bearing lingual facets, was found in Baleal. It can be attributed to an indeterminate eusauropod, possibly a basal macronarian. This tooth morphology is common in mamenchisaurids (Ouyang and Ye, 2002), basal macronarians (Osborn and Mook, 1921; Gilmore, 1925; Ostrom and McIntosh, 1966), and in the euhelopodid Euhelopus (Wilson and Upchurch, 2009). Heart-shaped teeth (Figure 11.2-3) are also reported from this area (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), which indicate the presence of turiasaurian eusauropods in the outcropping sediments north of Peniche. The SHN houses several specimens from Baleal, Pedras Muitas, and Almagreira (Figure 10.3), which still need preparation, including several axial and appendicular elements (e.g., Figure 11.8-10). One of those specimens is an anterior caudal vertebra with a slightly procoelous centrum (Figure 11.9, SHN 180). The overall morphology (e.g., slightly procoelous centrum and short neural spine with distal rugosities) resembles that of the anterior caudal vertebrae collected from the Spanish sediments of the Villar de Arzobispo Formation, in San Lorenzo (Riodeva), attributed by Cobos et al. (2011) to Turiasauria. The procoelous condition is shared with several clades within Eusauropoda (e.g., Wilson, 2002; Upchurch et al., 2004). Some compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (Figure 11.4, 11.7) collected in the Baleal-Pedras Muitas coastal section are deposited in the SHN collections.

Other sauropod remains were also identified to the north of Peniche. Most of these specimens are deposited in the collections of the MG, ML and SHN. A currently unpublished, partial spatulate tooth (Figure 11.1, MG 8783), bearing lingual facets, was found in Baleal. It can be attributed to an indeterminate eusauropod, possibly a basal macronarian. This tooth morphology is common in mamenchisaurids (Ouyang and Ye, 2002), basal macronarians (Osborn and Mook, 1921; Gilmore, 1925; Ostrom and McIntosh, 1966), and in the euhelopodid Euhelopus (Wilson and Upchurch, 2009). Heart-shaped teeth (Figure 11.2-3) are also reported from this area (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), which indicate the presence of turiasaurian eusauropods in the outcropping sediments north of Peniche. The SHN houses several specimens from Baleal, Pedras Muitas, and Almagreira (Figure 10.3), which still need preparation, including several axial and appendicular elements (e.g., Figure 11.8-10). One of those specimens is an anterior caudal vertebra with a slightly procoelous centrum (Figure 11.9, SHN 180). The overall morphology (e.g., slightly procoelous centrum and short neural spine with distal rugosities) resembles that of the anterior caudal vertebrae collected from the Spanish sediments of the Villar de Arzobispo Formation, in San Lorenzo (Riodeva), attributed by Cobos et al. (2011) to Turiasauria. The procoelous condition is shared with several clades within Eusauropoda (e.g., Wilson, 2002; Upchurch et al., 2004). Some compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (Figure 11.4, 11.7) collected in the Baleal-Pedras Muitas coastal section are deposited in the SHN collections.

The systematic affinities of the sauropod remains collected north of Peniche still need to be established in a detailed study. However, the currently available information allows the identification of possible turiasaurs and basal macronarians, including members of the clade that includes Titanosauriformes and Europasaurus (Figure 10).

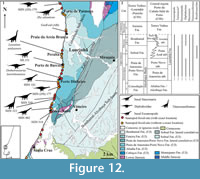

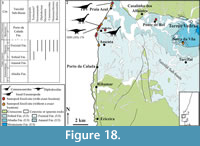

Praia da Consolação-Lourinhã-Torres Vedras coastal sector (Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15). This is the richest area in the Lusitanian Basin concerning Upper Jurassic dinosaur remains (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009, 2013) (Figure 12.1). A thick Upper Jurassic sedimentary sequence crops out in this sector and includes deposits of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo, Sobral and Bombarral Formations. This continental sedimentary sequence was deposited above the marine Abadia Fm. (Manuppella et al., 1999) (Figure 12.2). The type specimens of Lusotitan atalaiensis, Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis and Zby atlanticus (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas et al., 1992; Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mannion et al., 2012, 2013; Mateus et al., 2014) were found in this area of the Bombarral Sub-basin (Consolação Sub-basin following Taylor et al., 2014). In addition, many published and unpublished specimens, most of them housed in the palaeontological collections of the MG, ML, and SHN, were also collected in this area (Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Mateus, 2005; Yaguë et al., 2006; Mannion et al., 2012; Mocho et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014a).

Praia da Consolação-Lourinhã-Torres Vedras coastal sector (Figure 12, Figure 13, Figure 14, Figure 15). This is the richest area in the Lusitanian Basin concerning Upper Jurassic dinosaur remains (e.g., Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009, 2013) (Figure 12.1). A thick Upper Jurassic sedimentary sequence crops out in this sector and includes deposits of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo, Sobral and Bombarral Formations. This continental sedimentary sequence was deposited above the marine Abadia Fm. (Manuppella et al., 1999) (Figure 12.2). The type specimens of Lusotitan atalaiensis, Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis and Zby atlanticus (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas et al., 1992; Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mannion et al., 2012, 2013; Mateus et al., 2014) were found in this area of the Bombarral Sub-basin (Consolação Sub-basin following Taylor et al., 2014). In addition, many published and unpublished specimens, most of them housed in the palaeontological collections of the MG, ML, and SHN, were also collected in this area (Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Mateus, 2005; Yaguë et al., 2006; Mannion et al., 2012; Mocho et al., 2013a, 2013b, 2014a).

The Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation crops out in several areas along this sector, especially in the sedimentary sections from São Bernardino to Paimogo and from Porto Dinheiro to Praia de Santa Rita (Hill, 1988; Manuppella et al., 1999; Mateus et al., 2013). This late Kimmeridgian-basal Tithonian formation (Fürsich, 1981; Manuppella et al., 1999) is well-known for its abundant dinosaur fossil remains, including several sauropod specimens (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Dantas, 1990; Manuppella et al., 1999; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Ortega et al., 2009). This formation is interpreted as having been deposited in a distal alluvial to fluvial meandriform environment (Hill, 1988, 1989).

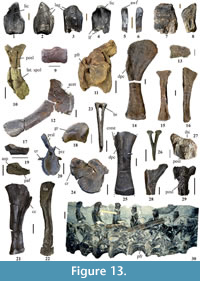

The holotype of Zby atlanticus (Figure 13.13-16, ML 368) was found in the Vale de Pombas cliffs (north of Forte de Paimogo), in the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation. This partial skeleton includes a tooth, a chevron, a right partial scapula, and coracoid, an almost complete right forelimb, and some indeterminate elements (Mateus, 2005, 2009; Mateus et al., 2014; pers. observ. PM). The material of Zby atlanticus was first attributed to the North American Morrison genus Camarasaurus (Mateus, 2005), and subsequently to Turiasaurus riodevensis (Mateus, 2009). Mateus et al. (2014) described the species Zby atlanticus as a member of Turiasauria. The affinities between Zby and the members of the Turiasauria clade were previously noted by other authors (Mateus, 2009; Mocho et al., 2012; Royo-Torres and Upchurch, 2012).

The holotype of Zby atlanticus (Figure 13.13-16, ML 368) was found in the Vale de Pombas cliffs (north of Forte de Paimogo), in the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation. This partial skeleton includes a tooth, a chevron, a right partial scapula, and coracoid, an almost complete right forelimb, and some indeterminate elements (Mateus, 2005, 2009; Mateus et al., 2014; pers. observ. PM). The material of Zby atlanticus was first attributed to the North American Morrison genus Camarasaurus (Mateus, 2005), and subsequently to Turiasaurus riodevensis (Mateus, 2009). Mateus et al. (2014) described the species Zby atlanticus as a member of Turiasauria. The affinities between Zby and the members of the Turiasauria clade were previously noted by other authors (Mateus, 2009; Mocho et al., 2012; Royo-Torres and Upchurch, 2012).

Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) reported the presence of some specimens collected north of the Forte de Paimogo (Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation). Non-sauropod dinosaurs were also found in this locality (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Escaso et al., 2008; Hendrickx and Mateus, 2014). A partial caudal series (MG 4978), with 15 caudal vertebrae, was found in São Bernardino (Peniche). A partial right humerus (Figure 13.25, MG 4976) of a sauropod was found in Praia dos Frades (Peniche) and was attributed to Apatosaurus alenquerensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957). This humerus has a crest on the posterior face of the proximal end, which is here identified as a shared feature with the humerus of Duriatitan humerocristatus, from the British lower Kimmeridge Clay Fm. (Barrett et al., 2010), being considered as cf. Duriatitan humerocristatus (Mocho et al., 2016a). An unpublished metacarpal I (SHN 583) found in Praia dos Frades (Peniche) shares the morphology of metacarpal I of Turiasaurus riodevensis and Zby atlanticus with the presence of a rough platform on the laterodorsal border of the distal end. It is thus tentatively considered as cf. Turiasauria.

A so far unprepared diplodocid specimen (Figure 13.27, SHN (JJS) 179) from Praia da Vermelha (Peniche, Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation), comprises axial and appendicular elements (Peniche; Mocho et al., 2014a). The morphology of the neural spines (posterior dorsal or anterior caudal), with a well-defined prespinal lamina, a rectangular shape (anteroposteriorly compressed), and with a slight dorsal bifurcation, is similar to the apomorphic morphology in the posterior dorsal and anterior caudal neural spines of diplodocids, such as Supersaurus, Dinheirosaurus, Diplodocus, and Barosaurus (e.g., Hatcher, 1901; Lull, 1919; McIntosh, 2005; Mannion et al., 2012; pers. observ., PM). Other unprepared sauropod specimens from this sector, also from the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Fm., are housed in the collections of the SHN and ML (see list of Mateus, 2005, for ML specimens; pers. observ., PM). Several teeth have also been found between Forte de Paimogo and Praia da Consolação, including heart-shaped teeth, probably referable to Turiasauria (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), spatulate teeth (e.g., SHN 516, SHN 540), attributed to indeterminate eusauropods, probably basal macronarians, and compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (e.g., SHN 546), a morphology shared with titanosauriforms and the basal macronarian Europasaurus. A skull fragment bearing heart-shaped teeth was found in Praia dos Frades (Figure 13.7-8, SHN 582) and probably represents a turiasaurian sauropod.

To the south of Porto Dinheiro, the type locality of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis (Dantas et al., 1992; Bonaparte and Mateus, 1999; Mannion et al., 2012), an extensive section of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation crops out. The border between the municipalities of Torres Vedras and Lourinhã is located in this relatively poorly prospected area. New discoveries reveal a rich dinosaur fauna, including theropods, ornithopods, thyreophorans, and sauropods, as well as other vertebrate groups, such as turtles and crocodyliforms (e.g., Malafaia et al., 2008; Escaso et al., 2010a, 2010b; Pérez-García and Ortega, 2011). Several fossil sites containing sauropods were found in this area, including some partial skeletons.

The first remains of the holotype of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis were identified in 1987, in the cliffs of Porto Dinheiro. Consequently, in 1988 and 1991, a team composed of members of the Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa, Portugal), Salamanca University (Salamanca, Spain) and GEAL (Lourinhã, Portugal) proceeded to the extraction of a series of partially articulated cervical and dorsal vertebrae, with associated dorsal ribs, as well as caudal vertebrae and pelvic elements (Figure 13.28-30, Figure 14.1) (Dantas et al., 1992). Bonaparte and Mateus (1999) defined a new diplodocid taxon, Dinheirosaurus alenquerensis, considered as a diplodocine form closely related to the North American Late Jurassic Supersaurus (Rauhut et al., 2005; Whitlock, 2011; Mannion et al., 2012; Tschopp and Mateus, 2013; Tschopp et al., 2015). In fact, Tschopp et al. (2015) suggested that Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis might represent a species of Supersaurus, proposing the new combination Supersaurus lourinhanensis. Several remains of the type specimen (ML 414), including several caudal vertebrae (pers. observ., FO and PM), need to be prepared for the confirmation or refutation of this hypothesis. The Dinheirosaurus type locality is stratigraphically close to the boundary between the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo and Sobral Formations (Manuppella et al., 1999; field observations, PM).

The first remains of the holotype of Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis were identified in 1987, in the cliffs of Porto Dinheiro. Consequently, in 1988 and 1991, a team composed of members of the Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa, Portugal), Salamanca University (Salamanca, Spain) and GEAL (Lourinhã, Portugal) proceeded to the extraction of a series of partially articulated cervical and dorsal vertebrae, with associated dorsal ribs, as well as caudal vertebrae and pelvic elements (Figure 13.28-30, Figure 14.1) (Dantas et al., 1992). Bonaparte and Mateus (1999) defined a new diplodocid taxon, Dinheirosaurus alenquerensis, considered as a diplodocine form closely related to the North American Late Jurassic Supersaurus (Rauhut et al., 2005; Whitlock, 2011; Mannion et al., 2012; Tschopp and Mateus, 2013; Tschopp et al., 2015). In fact, Tschopp et al. (2015) suggested that Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis might represent a species of Supersaurus, proposing the new combination Supersaurus lourinhanensis. Several remains of the type specimen (ML 414), including several caudal vertebrae (pers. observ., FO and PM), need to be prepared for the confirmation or refutation of this hypothesis. The Dinheirosaurus type locality is stratigraphically close to the boundary between the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo and Sobral Formations (Manuppella et al., 1999; field observations, PM).

Another partial diplodocid individual was found in Valmitão (Lourinhã), south of Porto Dinheiro (Mocho et al., 2014a). This specimen and the Dinheirosaurus holotype are the most complete diplodocids of the European Upper Jurassic record. The Valmitão specimen (SHN (JJS) 177) comprises elements of the axial skeleton (dorsal?, sacral, and anterior caudal vertebrae; ribs and chevrons) and pelvic girdle (ilia, ischia, and pubis) (Figure 13.10-12). SHN (JJS) 177 can be referred to Flagellicaudata on the basis of the presence of an expanded distal end of the ischia (following Whitlock, 2011). Rectangular anterior caudal neural spines in anterior view and the presence of diapophyseal laminae on the anterior caudal ribs support the assignation of SHN (JJS) 177 to Diplodocidae (sensu Whitlock, 2011). The presence of wing-like, anterior caudal ribs, dorsal concavity in the neural spines (slightly bifurcated), and ventral and lateral pneumaticity, suggest that the SHN (JJS) 177 is closely related to diplodocines, such as Diplodocus, Barosaurus, and Tornieria (Osborn, 1899; Hatcher, 1901; Lull, 1919; McIntosh, 2005; Remes, 2006; Whitlock, 2011; Tschopp et al., 2015).

Many sauropod specimens from the coastal cliffs between Porto Dinheiro and Santa Rita are housed in the SHN, and most still require preparation. Mateus (2005) also reported an appreciable number of specimens from this area and deposited in the ML. In 2003 and 2009, the SHN excavated a partial and articulated skeleton (Figure 14.2-3) in Santa Rita (Torres Vedras), including a partial tail and pelvis, associated with limb bones (Figure 13.26, SHN 534). The systematic affinities of this specimen still need to be clarified. Close to this quarry is the type locality of the pleurosternid turtle Selenemys lusitanica, also from the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Formation (Pérez-García and Ortega, 2011). Another fossil site prospected by the SHN is located in Porto Novo (Torres Vedras). Several axial and appendicular sauropod bones were recovered there. This specimen (SHN 002) shares the general morphology of the forelimb bones with the camarasaurid Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis; nevertheless, no diagnostic features can be identified. These two fossil sites are stratigraphically close to the upper boundary of the Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Fm. with the Sobral Fm. (Manuppella et al., 1999; field observations, PM). Another specimen (SHN 530), including sacral and caudal vertebrae, and appendicular bones (Figure 13.23-24), was found in the cliffs of Praia da Corva (Torres Vedras). The anterior caudal vertebrae (Figure 13.24) resemble the morphology present in Iberian turiasaurs (e.g., Casanovas et al., 2001), with slightly procoelous centra and fan-like caudal ribs, lacking the lateral and ventral pneumaticity and dorsalised neural spine, which would be typical of diplodocids (e.g., Hatcher, 1901; McIntosh, 2005; Remes, 2006). This specimen also preserves long and bridged anterior chevrons. An unpublished set of anterior, middle, and posterior caudal vertebrae (Figure 13.9), probably belonging to a single individual, was also found at Praia da Corva (SHN 523). It might represent an indeterminate titanosauriform, based on the presence of anteriorly displaced neural arches, pneumatic fossae (as occur in Giraffatitan or Andesaurus, Mannion and Calvo, 2011; Wedel and Taylor, 2013), and dorsoventrally compressed centrum. Finally, an also unpublished medium-sized individual (SHN 181) found in Valmitão is currently being prepared and described. It includes caudal vertebrae, and pectoral, pelvic, and hindlimb elements (Figure 13.19-22). This specimen presents several peculiar features and probably represents a new sauropod taxon. Furthermore, several teeth belonging to different morphotypes were recovered from the area between Porto Dinheiro and Santa Rita. These specimens include spatulate (Figure 13.3-4, SHN 513), and heart- (Figure 13.1-2, see Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), and compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (Figure 13.5-6, SHN 574, 575, 578).

The Sobral Formation is a lateral equivalent of the lowest part of the Bombarral Fm., representing a regional transgression (e.g., Hill, 1988). The Sobral Fm. was deposited in a deltaic to marginal marine environment (Hill, 1988; Manuppella et al., 1999). In the western part of the Bombarral Sub-basin (i.e., Consolação Sub-basin, following Taylor et al., 2014), this formation crops out in the coastal section from Peralta to Porto Dinheiro. Several sauropod specimens from the Sobral Fm. were reported, most notably the lectotype of Lusotitan atalaiensis. It was found in the Peralta cliffs, close to the Atalaia locality (Lourinhã). Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) originally considered this specimen to represent a new species of Brachiosaurus (at that time the genus Brachiosaurus included two species, the North American B. altithorax and the African B. brancai). Subsequently, Antunes and Mateus (2003) established the new genus, Lusotitan, to denominate this specimen. Mannion et al. (2013) presented a systematic revision of the Peralta specimen, considering it a basal macronarian, and, possibly, a brachiosaurid. The brachiosaurid affinities were recently supported by Mocho et al. (2016c). This specimen includes dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, dorsal ribs, chevrons, pelvic, forelimb, and hindlimb elements (Figure 15.9-14; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mannion et al., 2013; Mocho et al., 2016c). Several sauropod teeth were found at Peralta, including spatulate (Figure 15.1-2, Mocho et al., 2011) and heart- (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), and compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (Figure 15.3-6). Some isolated bones were also found in this region (Figure 15.7).

The Sobral Formation is a lateral equivalent of the lowest part of the Bombarral Fm., representing a regional transgression (e.g., Hill, 1988). The Sobral Fm. was deposited in a deltaic to marginal marine environment (Hill, 1988; Manuppella et al., 1999). In the western part of the Bombarral Sub-basin (i.e., Consolação Sub-basin, following Taylor et al., 2014), this formation crops out in the coastal section from Peralta to Porto Dinheiro. Several sauropod specimens from the Sobral Fm. were reported, most notably the lectotype of Lusotitan atalaiensis. It was found in the Peralta cliffs, close to the Atalaia locality (Lourinhã). Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957) originally considered this specimen to represent a new species of Brachiosaurus (at that time the genus Brachiosaurus included two species, the North American B. altithorax and the African B. brancai). Subsequently, Antunes and Mateus (2003) established the new genus, Lusotitan, to denominate this specimen. Mannion et al. (2013) presented a systematic revision of the Peralta specimen, considering it a basal macronarian, and, possibly, a brachiosaurid. The brachiosaurid affinities were recently supported by Mocho et al. (2016c). This specimen includes dorsal, sacral, and caudal vertebrae, dorsal ribs, chevrons, pelvic, forelimb, and hindlimb elements (Figure 15.9-14; Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957; Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mannion et al., 2013; Mocho et al., 2016c). Several sauropod teeth were found at Peralta, including spatulate (Figure 15.1-2, Mocho et al., 2011) and heart- (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), and compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (Figure 15.3-6). Some isolated bones were also found in this region (Figure 15.7).

Porto das Barcas is another relevant locality concerning dinosaur remains. The holotype of the ornithopod Eousdryosaurus (Dantas et al., 2000; Escaso et al., 2014) and nests with theropods eggs tentatively referred to Torvosaurus (Castanhinha et al., 2009; Araújo et al., 2013), were found there. Several sauropod specimens from Porto das Barcas were referred to Apatosaurus alenquerensis by Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957), including caudal vertebrae (MG 8800, 8805). MG 30390 is an unpublished partial skeleton that represents an indeterminate eusauropod, according to the presence of procoelous anterior caudal vertebrae, which are only known in Eusauropoda, such as mamenchisaurids, turiasaurs, diplodocids, and titanosaurs (e.g., Salgado, 1997; Wilson, 2002; Upchurch et al., 2004; Carballido and Sander, 2014). Another partial skeleton from Porto das Barcas is housed in the ML (ML 351), including a partial caudal series, sacrum and fibula (Antunes and Mateus, 2003; Mateus, 2005). Antunes and Mateus (2003) and Mateus (2005) referred this specimen to Lourinhasaurus alenquerensis, but this specimen does not bear diagnostic features that support this taxonomic assignment. The detailed preparation and study of this material is in process (RC, personal commun., 2015). Other specimens from this locality are housed in the ML and SHN (Mateus, 2005, pers. observ, PM), including heart-shaped (Mocho et al., 2012, 2016b), and compressed cone-chisel-shaped teeth (e.g., SHN 576). From Lage Fria (Porto das Barcas), Tschopp, and Mateus (2012) described a sternal plate (ML 684), suggesting that it might pertain to Turiasaurus riodevensis or Lusotitan atalaiensis. Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957, pl. XIII, figure 31-33) identified one vertebra from Porto das Barcas (MMLT 602528) as a posterior dorsal vertebra of Megalosaurus pombali. However, it represents an anterior caudal vertebra of an indeterminate sauropod. Another sauropod caudal vertebra (MMLT 602529) from Porto das Barcas was found in the collections of the MMLT, and probably corresponds to a vertebra mentioned by Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957, pg. 38). This vertebra represents an indeterminate sauropod.

The Tithonian Bombarral Formation crops out in the coastal section from Praia da Areia Branca to Paimogo (including Vale de Frades) (Figure 12.1). This formation lies above the Sobral Fm. (on the Forte de Paimogo locality) and Praia da Amoreira-Porto Novo Fm. (Hill, 1988; Manuppella et al., 1999). Furthermore, the Bombarral Fm. crops out in a wide area to the east of the Lourinhã Fault, from A-dos-Cunhados to Alcobaça (an area included in the Bombarral-Alcobaça Sub-basin by Taylor et al., 2014). The Bombarral Fm. was deposited in a coastal lagoonal to meandering fluvial environment (Manuppella et al., 1999).

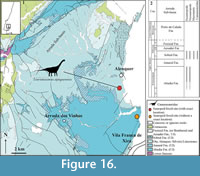

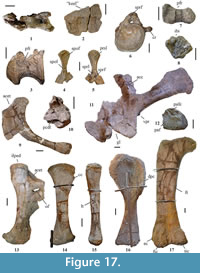

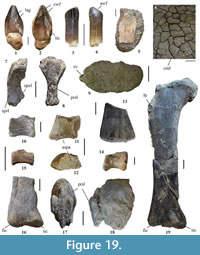

West of the Lourinhã Fault, the Bombarral Formation crops out between Peralta and Vale de Frades (south of Paimogo), and from south of Santa Rita to the town of Santa Cruz. Some bones from the Bombarral Fm. were reported by Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957). A partial left femur (Figure 15.15, MG 4986) was found in Praia da Areia Branca and was originally referred to Brachiosaurus atalaiensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957). It has recently been reinterpreted as an indeterminate titanosauriform (Mannion et al., 2013). Two caudal vertebrae housed in the palaeontological collections of the Museu Nacional de História Natural e da Ciência (Lisboa) were recovered in Areia Branca: an anterior caudal vertebra previously referred to Brachiosaurus atalaiensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957), and a procoelous anterior caudal centrum (Figure 15.8, MNHNUL.P.R27) referred to Apatosaurus alenquerensis (Lapparent and Zbyszewski, 1957). The first element can only be identified as an indeterminate sauropod. The second bone is recognised as belonging to an indeterminate eusauropod, based on the procoelous condition, a feature present in several eusauropod groups (e.g., Salgado et al., 1997; Wilson, 2002; Upchurch et al., 2004; Carballido and Sander, 2014). Lapparent and Zbyszewski (1957, pg. 17) reported the occurrence of a small femur from a sauropod from Vale de Frades, but its present whereabouts are unknown.