| |

DESCRIPTION OF THE RIB CAGE,

FORELIMB, AND GIRDLE

The anatomy of the ribs, pectoral girdle, and forelimb of

Chasmosaurus irvinensis is closely comparable to that described in other

ceratopsids (e.g., Hatcher et al. 1907; Brown 1917; Lull 1933, Dodson et al.

2004). The anatomy of the ribs, pectoral girdle, and forelimb of

Chasmosaurus irvinensis is closely comparable to that described in other

ceratopsids (e.g., Hatcher et al. 1907; Brown 1917; Lull 1933, Dodson et al.

2004).

Almost all of the ribs and presacral vertebral column of CMN

41357 are preserved. Although the vertebral column is badly distorted and some

of the ribs are crushed, there is a good representative sample of relatively

undistorted ribs from all regions of the rib cage. They confirm that the

posterior cervical and anterior-most thoracic ribs turn sharply ventrally at

their necks, and are otherwise almost completely straight, resulting in a

distinctly narrow chest between the pectoral girdles (Paul and Christiansen

2000).

A gentle curvature develops by the fourth or fifth thoracic rib, and by

about the ninth thoracic rib, the rib cage forms a broad barrel. A gentle curvature develops by the fourth or fifth thoracic rib, and by

about the ninth thoracic rib, the rib cage forms a broad barrel.

Both scapulocoracoids are preserved (Figure 1). Although the

coracoids have been folded under slightly, the morphology of the elements is

clear. The medial surface of the scapular blade is only slightly concave. The

strongly concave coracoid contribution to the glenoid "closes" the articular

surface proximally, resulting in a glenoid that faces at right angles to the

long axis of the scapulocoracoid.

The humerus, ulna, and radius (Figure 2, Figure 3) are all slightly

crushed, but are well preserved and can be articulated without difficulty. As in

other neoceratopsids (e.g., Johnson and Ostrom 1995), the proximal humeral

condyle is located on the dorsal (external) surface of the proximal humeral

expansion and is offset to a position posterior to the axis of the humeral

shaft. The distal expansion bears two distal condyles separated by a groove (the

trochlea) to receive a ridge on the proximal articular surface of the ulna. The

anterior (preaxial) condyle bears a convex capitular facet on its ventral

(extensor) surface to receive the radius. The humerus, ulna, and radius (Figure 2, Figure 3) are all slightly

crushed, but are well preserved and can be articulated without difficulty. As in

other neoceratopsids (e.g., Johnson and Ostrom 1995), the proximal humeral

condyle is located on the dorsal (external) surface of the proximal humeral

expansion and is offset to a position posterior to the axis of the humeral

shaft. The distal expansion bears two distal condyles separated by a groove (the

trochlea) to receive a ridge on the proximal articular surface of the ulna. The

anterior (preaxial) condyle bears a convex capitular facet on its ventral

(extensor) surface to receive the radius.

The proximal articular surface of the

ulna is divided into two concave surfaces by a ridge that fits into the

trochlear notch of the humerus. The posterior of these two surfaces articulates

with the anterior half of the posterior distal humeral condyle, and the anterior

surface with the posterior half of the anterior humeral condyle. A prominent olecranon projects proximally from the rim of the articular surface. The radius

bears an oval, concave terminal facet that articulates with the ventral (capitular)

surface of the anterior humeral condyle. When the epipodium is in articulation

with the humerus, the proximal head of the radius lies in a bowl-shaped

depression on the flexor surface of the ulna. The long axes of the ulna and

radius diverge distally. The distal end of the epipodium, formed by the expanded

distal ends of the two bones, forms a broad arc. The proximal articular surface of the

ulna is divided into two concave surfaces by a ridge that fits into the

trochlear notch of the humerus. The posterior of these two surfaces articulates

with the anterior half of the posterior distal humeral condyle, and the anterior

surface with the posterior half of the anterior humeral condyle. A prominent olecranon projects proximally from the rim of the articular surface. The radius

bears an oval, concave terminal facet that articulates with the ventral (capitular)

surface of the anterior humeral condyle. When the epipodium is in articulation

with the humerus, the proximal head of the radius lies in a bowl-shaped

depression on the flexor surface of the ulna. The long axes of the ulna and

radius diverge distally. The distal end of the epipodium, formed by the expanded

distal ends of the two bones, forms a broad arc.

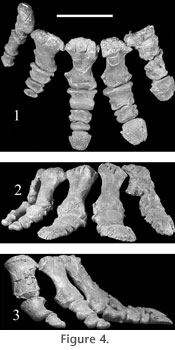

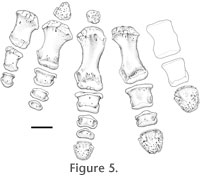

As in other well-preserved neoceratopsid forelimbs (e.g.,

Centrosaurus AMNH 5351, Brown 1917), all but the third and fourth distal

carpals are absent, and probably never ossified. The entire metacarpus and manus

(Figure 4) are well preserved in articulation. Five digits are present. As in

Centrosaurus apertus (Brown 1917), the phalangeal formula is 2-3-4-3-2

(Figure 5). Terminal phalanges of digits 1-3 show clear evidence of keratinous

hooves.

Terminal phalanges 1 and 2 are distinctly larger, suggesting that the preaxial (medial) side of the manus bore most of the weight or sustained more

stress during locomotion. The distal-most phalanx on each of digits 4 and 5

bears what appears to be a terminal articular facet. However, as in the

similarly articulated and well-preserved mani of Centrosaurus apertus

(Brown 1917), there is no trace of a hoof-bearing terminal phalanx associated

with either digit, suggesting that they were not present in life, or possibly

never ossified. The distal articular facets of the metacarpals have extensive

dorsal exposure, indicating considerable potential for dorsiflexion of the manus,

permitting a digitigrade stance. The combined proximal articular surface of the

articulated metacarpus forms a broad arch (Figure 4.1). As a result, the

digits are distinctly splayed (Figure 4.1). Terminal phalanges 1 and 2 are distinctly larger, suggesting that the preaxial (medial) side of the manus bore most of the weight or sustained more

stress during locomotion. The distal-most phalanx on each of digits 4 and 5

bears what appears to be a terminal articular facet. However, as in the

similarly articulated and well-preserved mani of Centrosaurus apertus

(Brown 1917), there is no trace of a hoof-bearing terminal phalanx associated

with either digit, suggesting that they were not present in life, or possibly

never ossified. The distal articular facets of the metacarpals have extensive

dorsal exposure, indicating considerable potential for dorsiflexion of the manus,

permitting a digitigrade stance. The combined proximal articular surface of the

articulated metacarpus forms a broad arch (Figure 4.1). As a result, the

digits are distinctly splayed (Figure 4.1).

|