|

|

REsults

Virtual skeletal mount of Plateosaurus

Vertebral column. Plateosaurus has 10 cervicals (plus a

rudimentary proatlas), 15 dorsal and three sacral vertebrae. The tail is

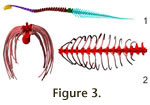

composed of 45 vertebrae in GPIT1. Figure 3.1 shows a lateral view of the

cervical, dorsal, and caudal series of GPIT1 in osteologically neutral position. Vertebral column. Plateosaurus has 10 cervicals (plus a

rudimentary proatlas), 15 dorsal and three sacral vertebrae. The tail is

composed of 45 vertebrae in GPIT1. Figure 3.1 shows a lateral view of the

cervical, dorsal, and caudal series of GPIT1 in osteologically neutral position.

The cervical column articulates in a nearly straight line, parallel to the long

axis of the cervical centra. However, this line is not perpendicular to the

anterior and posterior faces of the vertebrae, but ascends anteriorly.

Therefore, ONP displaces the head dorsally, resulting in a skull position at or

above shoulder height, depending on the angle of the anterior face of the first

dorsal relative to the exterior.

The anterior dorsals arch dorsally (dorsals 1 through 4), while the middle part curves

markedly ventrally (dorsals 5 through 10). Further posteriorly the dorsal column is

nearly straight. In all, the downward curve results in a ventral rotation of the

long axis of dorsal 5 by 22°, while the anterior upward curve angles the base of the

neck up by 12° compared to dorsal 5, and 15° down compared to D15. Therefore, if the

sacrum is placed with its long axis horizontal, the neck is attached at a slight

downward angle, and the 'stepping up' of the cervical is required to bring the

head to above shoulder level in ONP. This position is similar to that of SMNS

13200 as figured in Huene (1926). The slightly different curvature of SMNS 13200

can be explained by the damaged dorsal 6 and the slight disarticulation between

dorsals 4 and 5 (Huene 1926: plate II).

In the anterior tail, the neutral pose placing the centra faces parallel (ONP)

cannot be created. Nearly all vertebra show slight keystoning. As noted by

Moser

(2003), this keystoning is intrinsic to the osteology, but its degree varies. In

GPIT1 the variance is lower than in the material from Ellingen (Germany)

described in detail by Moser

(2003), which may be caused by a lower degree of taphonomic deformation. If the centra are placed at an angle to bring their

anterior and posterior faces into a parallel position, the haemal arches can not

be fitted to their articulation surfaces on the vertebrae. Neutral pose is

supposed to provide the maximum contact of articular surfaces. Omitting the

haemal arches, or moving them out of close articulation, would violate that

principle. To accommodate the zygapophyses in articulation dorsally and the

haemal arches in close articulation ventrally, the intervertebral disks were

reconstructed as having slightly greater thickness ventrally than dorsally,

i.e., slightly wedge-shaped. Adjustment for the haemal arches results in a

straight tail, with varying intervertebral disc thickness and shape.

Ribcage. The articulations between ribs and dorsal

vertebrae show that the anterior body was narrow from side to side (Figure 3.2).

As in all dinosaurs, the ribs of Plateosaurus have two heads (Huene

1926), the dorsal capitulum that articulates with the diapophysis on the

transverse process of the vertebra, and the ventral tuberculum, which contacts

the parapophysis. The ribs move by rotating around the axis connecting the two

articulations (Mallison in press). Whether the rib motion enlarges the ribcage

volume, e.g., for breathing in as in humans, or whether the rib motion has no

influence on the body volume depends on the orientation of the axis. In

Plateosaurus, the first five dorsal ribs move antero-posteriorly, while all

later body ribs swing outwards, increasing the volume of the body cavity (Mallison

in press). For the analysis presented here, an intermediate position of the ribs

was chosen. In- or exhalation does not significantly change the position of the

COM, because there is practically no antero-posterior motion of large tissue

volumes.

Pectoral girdle and forelimb. The pectoral girdle and

the functionally associated axial elements are incompletely preserved in GPIT1.

Only the co-ossified scapula and coracoid are preserved on each side, while the

left clavicle and sternals are missing. The right clavicle is partially

preserved and attached to the coracoid by sediment. It is a thin rod, as

described by Huene (1926). The scapulacoracoids follow the usual prosauropod

pattern in their general morphology, but show a number of peculiarities (Remes

2008), some of which have a profound impact on the interpretation of possible

locomotion poses. Most importantly, the glenoid is a simple trough, restricted

to the caudal margin of the scapulocoracoid. It does not extend to the lateral

surface of scapula or coracoid, and only the anteromedial rotation of the entire

scapulacoracoids leads to a caudoventrolateral orientation of the glenoid.

If the scapula is placed at an angle shallower than 45° in reference to the

sacrum–1st dorsal line, either the pectoral girdle projects forward

beyond the second to last cervical, a position contrary to all articulated

finds, or the scapular blade overlaps beyond the fifth dorsal. Due to the

lateral expansion of the ribcage during breathing, this would lead to lateral

displacement of the dorsal end of the scapula, and thus require a hinge-joint

motion between the coracoids. The forelimbs would therefore move laterally with

each breath. Additionally, any force pressing dorsally on the glenoid, e.g.,

compressive forces in the forelimb during locomotion, would tend to rotate the

scapula anterodorsally. A placement of the scapula steeper than 65° is

unreasonable, as it would lead to a nearly horizontal orientation of the

coracoids, and direct the glenoid exclusively posteriorly.

Angles of the scapula between 45° and 65° appear reasonable, as they do not push

the coracoids too far forward, but also place the tip of the scapular blade at

the level of the fourth dorsal (Figure 4.1). Such a position, with tightly

spaced coracoids, is biomechanically advantageous, as the girdle then can form a

strong brace, both for projecting large forces through the arms, and as a

support structure when the animal is lying on the ground.

Remes (2008) also

suggested this arrangement based on an analysis of the myology in basal

sauropodomorphs. In Massospondylus, a close relative of Plateosaurus,

Yates and Vasconcelos (2005) found articulated clavicles that were arranged in a furcula-like manner, touching at the midline. This further confirms the narrow

arrangement of the shoulder girdle. For Plateosaurus, this condition of

touching but not co-ossified coracoids and clavicles was already explicitly

mentioned by Huene (1926) in several skeletons. The scapulae cannot be separated

laterally and shifted dorsoposteriorlys on the side of the ribcage as suggested

by the mounts in the SMNS. It is important to note that dorsolaterally shifting

the scapulocoracoids forces a quadrupedal Plateosaurus into a sprawled

forelimb posture, with an extremely reduced functional forelimb length. Angles of the scapula between 45° and 65° appear reasonable, as they do not push

the coracoids too far forward, but also place the tip of the scapular blade at

the level of the fourth dorsal (Figure 4.1). Such a position, with tightly

spaced coracoids, is biomechanically advantageous, as the girdle then can form a

strong brace, both for projecting large forces through the arms, and as a

support structure when the animal is lying on the ground.

Remes (2008) also

suggested this arrangement based on an analysis of the myology in basal

sauropodomorphs. In Massospondylus, a close relative of Plateosaurus,

Yates and Vasconcelos (2005) found articulated clavicles that were arranged in a furcula-like manner, touching at the midline. This further confirms the narrow

arrangement of the shoulder girdle. For Plateosaurus, this condition of

touching but not co-ossified coracoids and clavicles was already explicitly

mentioned by Huene (1926) in several skeletons. The scapulae cannot be separated

laterally and shifted dorsoposteriorlys on the side of the ribcage as suggested

by the mounts in the SMNS. It is important to note that dorsolaterally shifting

the scapulocoracoids forces a quadrupedal Plateosaurus into a sprawled

forelimb posture, with an extremely reduced functional forelimb length.

The width of the shoulder girdle has been differently reconstructed with the

'old' museum mounts in the SMNS separating the coracoids by more than the length

of a coracoid and placing the scapula blade almost parallel to the dorsal

series. However, these mounts show a grossly exaggerated width of the ribcage.

GPIT1 and GPIT2 were mounted with a narrower arrangement by Huene, as was AMNH

6810, another excellently preserved skeleton from Trossingen. As shown by

Mallison (2007,

in press), the ribcage is high-oval in the shoulder area, and

only widens further posteriorly. Also, the anterior ribs sweep caudally

slightly, allowing for a narrow girdle architecture, with steeply inclined

scapula blades and medially almost contacting coracoids. Motion is restricted to

antero-posterior sweeps (Mallison in press) only in the first five dorsal ribs,

while further posteriorly there is a significant lateral expansion.

Huene (1926)

already mentioned that in SMNS 13200 these five ribs are significantly thicker

and sturdier than those of more posterior dorsals (see

Figure 4.1). They also

have a flattened cross-section. This flattening is not caused by the ribs'

attachment to the sternum, as the rough thickened distal ends indicating

attachment are found on the first eight ribs. The most plausible explanation is

that only the first five ribs had to absorb large forces transmitted through the

pectoral girdle. Recently,

Fujiwara et al. (2009) indeed found that more robust

ribs are present where the M. serratus attaches to the ribcage in quadrupeds.

The proximal end of the humerus is broad and dorso-ventrally compressed. This

indicates that a rotation of the humerus head in the glenoid, as is seen in

animals with sprawling gaits (Goslow and Jenkins 1983;

Landsmeer 1983,

1984;

Meers 2003), was not possible. Due to the simple shape of the glenoid,

protraction-extension is limited to an ~80° angle, from 55° to 135° in relation

to the long axis of the scapular blade (Figure 4.2). Therefore, if the scapula

is placed at a 35° angle from the horizontal, the humerus can not be protracted

beyond vertical. The possible amount of abduction can not be ascertained, but

any angle greater than 30° leads to an instable position, in which only limited

forces can be placed on the joint. Large forces would lead to a medial shifting

of the humeral head, as the glenoid does not contain it laterally in any way.

These findings, more details on which can be found in Mallison (in press),

confirm the results of

Bonnan and Senter (2007). Due to the medial rotation of

the glenoid axis, retraction of the humerus displaces the elbow laterally. A

purely parasagittal motion of the humerus seems not possible. The cranioventral

torsion of the distal end of the humerus relative to the proximal end is usually

45° in prosauropods (Remes 2008), but only 30° in Plateosaurus.

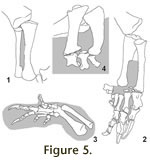

Radius and ulna can only be articulated with the distal end of the humerus if

they are placed into close proximity with each other (Mallison in press, fig.

5). The imperfect preservation of the distal humeral condyles allows separating

radius and ulna by a few millimeters or up to about 2 cm. A tight arrangement

seems more realistic, especially since the lateral side of the triangular distal

end of the ulna forms an articular surface conforming to the shape of the

proximal radius. Distally, both bones do not form contact surfaces, and are

spaced slightly apart in all articulated finds (Figure 5). In GPIT2, the left

radius and ulna each show a small deformation where they were pressed into each

other during fossilization. This relatively tight placement allows only minimal

motion between radius and ulna, making full pronation by rotation of the radius

impossible. Several other factors also indicate that Plateosaurus was not

capable of significantly pronating the hand this way: the proximal end of the

radius is oval in circumference, with a ratio between the longest and shortest

axes of 1.8:1 (Mallison in press, fig. 5). Rotating the radius head requires a

circular circumference as seen in humans and cats. Only a sliding motion, which

is not seen in any extant animal capable of pronation, remains possible. Bonnan and Senter (2007) investigated the ability to pronate the manus

using an extant phylogenetic bracket approach and found none of the extant

outgroup taxa capable of pronation. Additional evidence comes from the skeletons

that were found in articulation in Trossingen (GER) and Frick (CH). The animals

were trapped in mud (Sander 1992), their hindlimbs stuck while the forelimbs

were still free. A quadruped should in such a situation attempt to push itself

out of the mud with its forelimbs. However, not a single one of the skeletons

shows a forelimb with a pronated manus close to the body midline. Rather, the

arms are widely spread (SMNS F33), placed under the belly with the palm facing

dorsally (MSF 23 right arm), or widely abducted with strongly flexed elbow,

wrist, and fingers and medially directed palm in full supination (MSF 23 left

arm). Huene (1928: plate X) figured a quarry map of GPIT1, the only find in

which one arm potentially shows manus pronation (left forelimb). However, the

overlap pattern of the girdle and limb bones (right scapula overlaps right

humerus, left humerus wedged between the coracoids, etc.) indicates that the

skeleton was significantly displaced in a semi-macerated state, so that the

position of the manus as found is not indicative of the potential motion range

in vivo. Radius and ulna can only be articulated with the distal end of the humerus if

they are placed into close proximity with each other (Mallison in press, fig.

5). The imperfect preservation of the distal humeral condyles allows separating

radius and ulna by a few millimeters or up to about 2 cm. A tight arrangement

seems more realistic, especially since the lateral side of the triangular distal

end of the ulna forms an articular surface conforming to the shape of the

proximal radius. Distally, both bones do not form contact surfaces, and are

spaced slightly apart in all articulated finds (Figure 5). In GPIT2, the left

radius and ulna each show a small deformation where they were pressed into each

other during fossilization. This relatively tight placement allows only minimal

motion between radius and ulna, making full pronation by rotation of the radius

impossible. Several other factors also indicate that Plateosaurus was not

capable of significantly pronating the hand this way: the proximal end of the

radius is oval in circumference, with a ratio between the longest and shortest

axes of 1.8:1 (Mallison in press, fig. 5). Rotating the radius head requires a

circular circumference as seen in humans and cats. Only a sliding motion, which

is not seen in any extant animal capable of pronation, remains possible. Bonnan and Senter (2007) investigated the ability to pronate the manus

using an extant phylogenetic bracket approach and found none of the extant

outgroup taxa capable of pronation. Additional evidence comes from the skeletons

that were found in articulation in Trossingen (GER) and Frick (CH). The animals

were trapped in mud (Sander 1992), their hindlimbs stuck while the forelimbs

were still free. A quadruped should in such a situation attempt to push itself

out of the mud with its forelimbs. However, not a single one of the skeletons

shows a forelimb with a pronated manus close to the body midline. Rather, the

arms are widely spread (SMNS F33), placed under the belly with the palm facing

dorsally (MSF 23 right arm), or widely abducted with strongly flexed elbow,

wrist, and fingers and medially directed palm in full supination (MSF 23 left

arm). Huene (1928: plate X) figured a quarry map of GPIT1, the only find in

which one arm potentially shows manus pronation (left forelimb). However, the

overlap pattern of the girdle and limb bones (right scapula overlaps right

humerus, left humerus wedged between the coracoids, etc.) indicates that the

skeleton was significantly displaced in a semi-macerated state, so that the

position of the manus as found is not indicative of the potential motion range

in vivo.

The carpus is not well preserved in GPIT1 and GPIT2, but MNHB Skelett XXV from

Halberstadt has five carpals. The proximal row consists of two large elements

that are shallow triangular in plantar view. The radiale has contact with the

radius, metacarpal I, and the ulnare, as well as a small articulation with a

distal carpal. The ulnare is situated between the ulna and the distal carpals.

It is unclear whether it had any contact to the radius. The distal carpal row is

formed by a flat, box-shaped bone closely corresponding to the form of and in

close contact with the proximal end of metacarpal II, and two small rounded

elements situated between the ulna and metacarpals III and IV. These do not

block metacarpal V from contact with the ulna. The range of motion in the carpus

is difficult to determine.

Bonnan and Senter (2007) concluded that rotational or

twisting motions are made impossible by the block-like structure of the carpus.

Extension and strong flexion, however, possibly to a similar degree as in

humans, appear possible.

Metacarpals I through III articulate tightly with their proximal ends. Distally,

they show minimal splaying. Metacarpal IV also has an articulation surface for

metacarpal III, but angles laterally 20°. Metacarpal V has two distinct

articulation surfaces, and contacts both metacarpal IV and the ulna. It angles

laterally about 50° from metacarpal III.

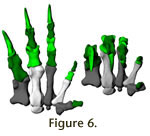

The manus digits of Plateosaurus are highly unequal, with digit I

developed as a strong grasping claw, and digit IV and V much reduced.

Paul

(1987, 1997,

2000) depicted Plateosaurus in a The manus digits of Plateosaurus are highly unequal, with digit I

developed as a strong grasping claw, and digit IV and V much reduced.

Paul

(1987, 1997,

2000) depicted Plateosaurus in a quadrupedal pose, with the

first digit medially rotated by almost 90°, so that the claw is in a horizontal

position at mid-stance. Digital manipulation of the scans of GPIT1 shows that

this angle is close to 27° during hyperextension and decreases to only 13° at

maximum flexion, because the significant size difference in the articular

condyles of metacarpal I are partially countered by an asymmetrically shaped

proximal articulation surface on the first phalanx of digit I. The significance

of the size difference lies with the larger medial condyle being subjected to

higher forces, not with a canting of the main axis of the digit. Additionally,

as pointed out by Galton (1976), in Anchisaurus, which has a similarly

shaped hand, during flexion the ungual phalanx rotates laterally, and thus

nearly lines up with the second and third digits. The latter are unremarkable,

with strong claws. However, it is important to note that hyperextension is less

pronounced than in the toes, even though there are distinct but shallow

hyperextension pits. In contrast to the first three, digits IV and V do not show

well-developed trochleae, resulting in greater freedom of motion but a reduced

ability to withstand forces. The entire hand (Figure 6,

Video 2) appears to be

adapted to strong grasping, with some ability to oppose digits IV and V. quadrupedal pose, with the

first digit medially rotated by almost 90°, so that the claw is in a horizontal

position at mid-stance. Digital manipulation of the scans of GPIT1 shows that

this angle is close to 27° during hyperextension and decreases to only 13° at

maximum flexion, because the significant size difference in the articular

condyles of metacarpal I are partially countered by an asymmetrically shaped

proximal articulation surface on the first phalanx of digit I. The significance

of the size difference lies with the larger medial condyle being subjected to

higher forces, not with a canting of the main axis of the digit. Additionally,

as pointed out by Galton (1976), in Anchisaurus, which has a similarly

shaped hand, during flexion the ungual phalanx rotates laterally, and thus

nearly lines up with the second and third digits. The latter are unremarkable,

with strong claws. However, it is important to note that hyperextension is less

pronounced than in the toes, even though there are distinct but shallow

hyperextension pits. In contrast to the first three, digits IV and V do not show

well-developed trochleae, resulting in greater freedom of motion but a reduced

ability to withstand forces. The entire hand (Figure 6,

Video 2) appears to be

adapted to strong grasping, with some ability to oppose digits IV and V.

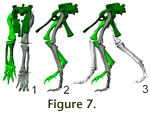

Pelvic girdle and hindlimb. The hindlimb of Plateosaurus

(Figure 7) shows a number of adaptations to cursoriality compared to basal

archosaur taxa. The femur is long, and its head is medially offset, indicating a

parasagittal limb posture, as already concluded by

Huene (1926,

1928). The

distal femoral condyles in Plateosaurus face slightly caudally, which

indicates that the knee could not be fully straightened. Combined with the

longitudinal curvature of the femur shaft and its sub-circular cross-section

this means that Plateosaurus had a permanently flexed limb posture, and

that the femur was not held vertically during standing or at mid-stance. longitudinal curvature of the femur shaft and its sub-circular cross-section

this means that Plateosaurus had a permanently flexed limb posture, and

that the femur was not held vertically during standing or at mid-stance.

In anterior view, the probable rotation axis of the knee joint is canted against

the shaft of the femur by approximately 70° (Figure 7.1). The axis of the

proximal end is hard to determine, but appears to be roughly parallel to that of

the knee. If the femur is placed in the acetabulum so that the axis of the knee

joint is horizontal, the shaft is inclined medially and the approximate center

of the knee is placed directly ventrally from the hip joint. In

Figure 7.1, the

femur is shown adducted slightly more, so that the first pedal digit is placed

under the body midline. Such a position under or nearly under the COM is

necessary for walking gaits in bipeds, and today seen in practically all

quadrupeds.

Gatesy (1990) showed that non-avian dinosaurs use femur retraction as the major

component in caudally directed foot displacement, thus generating most of the

required force in the M. caudofemoralis. As this was certainly also the case in

Plateosaurus, it is reasonable to assume that the femur covered a large arch

during locomotion. A limit on protraction is imposed by the pubes at low

abduction angles. Retraction is not hindered by the ischia, so a maximum angle

must be estimated based on the path of the M. caudofemoralis longus and its

maximum contraction. This at best is educated guesswork, but it seems

reasonable, given the position of the tail in relation to the pelvis, to assume

that during locomotion retraction was limited to a position in which the femur

shaft is parallel to the ischia, as at this point all ischiofemoral musculature

has no retraction function left at all. If this is correct, then the angle that

the femur can cover without significant abduction is 65°.

Figure 7.2 depicts the hindlimbs and pelvic girdle in lateral view, with a suggested stride length of 1

m for a normal walk. This correlates roughly to a walking speed of 3.7 km/h,

using an average of Alexander's (1976) and

Thulborn's (1990) formulas. For this

stride length, the femora need only cover a 50° angle. For angles larger than

65°, abduction is required so that the femur passes the pubis laterally, or

retraction to beyond the level of the ischia. Compared to the neutral position

chosen here (distal end of femur directly ventral from acetabulum in anterior

view), the former requires 20° abduction. It appears therefore doubtful whether

significantly larger protractions than to the level of the pubis were possible.

Not only is all pubofemoral musculature ineffective for protraction when the

femur is close to the pubis and has a purely adducting effect. Also, there is no

greatly enlarged proacetabular process on the ilium of Plateosaurus.

Therefore, the iliofemoral muscles that still have a protracting component are

weak. Passive protraction, e.g. by transfer of rotational inertia from the shank

to the thigh, is possible, but only effective at very high limb swing speeds

(running gaits). One must assume that femur motion during normal locomotion was

limited to the mentioned 65° at medium speeds, while slower speeds probably used

less retraction. The center of mass was located in front of the acetabulum, and

mid-stance position as reconstructed here was at slight protraction (20° from

vertical, Figure 7.2).

The tibia shaft is straight, and the tibia expands slightly proximally, but

there is no distinct cnemial crest projecting anteriorly in lateral view. Knee

extension therefore did not form a major part of locomotory limb motions,

excluding the possibility of a hopping gait as suggested by

Jaekel (1913-14),

and probably also a bounding gallop as suggested by

Paul (2000). In the tibia

and fibula there is no canting between the long axis of the shaft and the

apparent joint axes. Distally, the tibia articulates tightly with the massive astragalus. Four more carpals, a calcaneum and three distal tarsals, are

preserved in GPIT1. On the left foot of MB.R.4404, three distal tarsals with

very similar shapes to those of GPIT1 are preserved, so the likeliness of

taphonomic deformation is low. The ankle is wide and flattened, with no bony

structure forming a pronounced heel, and no indication of a large cartilaginous

projection. Therefore, extension moments around the ankle were either low or

created primarily through high muscular forces. In contrast, mammals use a large

lever arm in their ankles, the tuber calcanei (Romer 1949). The ankle of GPIT1

forms a hinge joint, the axis of which is almost parallel to the knee (Figure

7.1). The range of motion is large, covering at least 170°. This would allow any

limb pose from straight to completely folded, as in resting birds. Astragali of

other individuals show a very similar morphology, if taphonomic deformation is

taken into account. As a result of the arrangement of the joint axes, placing

the femur canted inwards so that the knee axis is horizontal results in a

vertical position of the lower limb, and places the third toe ventrally below

acetabulum in anterior view (but not in lateral view, because the COM lies in

front of the acetabulum).

The metatarsals articulate tightly (Figure 8.1), with clearly demarcated, large

articulation facets on their lateral sides. These, however, do not run down the

shafts to a great extent, since the proximal articular ends are much wider than

the shafts. Some previous reconstructions (e.g., the 'old' SMNS mounts) have

therefore been created with splayed metatarsals. However, such a placement is

not supported by the skeletons found in Trossingen, Halberstadt, and Frick,

where all feet found in articulation show the metatarsals closely touching

proximally and almost touching distally (Figure 8.2-4). There is no splaying in

these finds, which would also be biomechanically unsound. Splayed metatarsals

result in a larger, thus heavier foot, which decreases the swing frequency of

the limb. Additionally, splaying causes lateral bending moments in the lateral

and medial metatarsals. These could result in adaptation of the shape of the

metatarsals and toes, e.g., unequal condyles on the interphalangeal joints and

asymmetrical metatarsal shaft cross sections, as well as laterally curved

metatarsal shafts, which are not present in Plateosaurus. A broader foot

would offer more lateral stability, but in extant cursors feet are reduced in

size, because the above mentioned factors outweigh the advantage of slightly

greater stability. Only animals regularly walking on instable substrates such as

snow and sand (e.g., arctic foxes and camels, respectively) show slightly larger

support areas than their relatively moving on stable ground. Even in them the

size increase in the foot is proportionally much smaller than splaying of the

metatarsals would create in Plateosaurus. The metatarsals articulate tightly (Figure 8.1), with clearly demarcated, large

articulation facets on their lateral sides. These, however, do not run down the

shafts to a great extent, since the proximal articular ends are much wider than

the shafts. Some previous reconstructions (e.g., the 'old' SMNS mounts) have

therefore been created with splayed metatarsals. However, such a placement is

not supported by the skeletons found in Trossingen, Halberstadt, and Frick,

where all feet found in articulation show the metatarsals closely touching

proximally and almost touching distally (Figure 8.2-4). There is no splaying in

these finds, which would also be biomechanically unsound. Splayed metatarsals

result in a larger, thus heavier foot, which decreases the swing frequency of

the limb. Additionally, splaying causes lateral bending moments in the lateral

and medial metatarsals. These could result in adaptation of the shape of the

metatarsals and toes, e.g., unequal condyles on the interphalangeal joints and

asymmetrical metatarsal shaft cross sections, as well as laterally curved

metatarsal shafts, which are not present in Plateosaurus. A broader foot

would offer more lateral stability, but in extant cursors feet are reduced in

size, because the above mentioned factors outweigh the advantage of slightly

greater stability. Only animals regularly walking on instable substrates such as

snow and sand (e.g., arctic foxes and camels, respectively) show slightly larger

support areas than their relatively moving on stable ground. Even in them the

size increase in the foot is proportionally much smaller than splaying of the

metatarsals would create in Plateosaurus.

All toes of GPIT1 are almost straight, in contrast to Skelett XXV (MB.R.4404)

from Halberstadt, in which the fourth toe curves laterally. Similarly, in GPIT1

toes 1 through 3 are canted slightly medially compared to the long axis of the

metatarsus, though beveled distal condyles of the metatarsals. The fourth

metatarsal, however, is canted laterally. In contrast, in Skelett XXV, toes 1

through 3 are canted strongly medially, and the base of the fourth toe is

perpendicular to the long axis of the metatarsus. It is unclear whether this

difference is caused by intraspecific variation, or indicates that the two

individuals belong to separate species.

The hindlimb digits of GPIT1 allow somewhat larger hyperextension angles than in

the forelimb, indicative of a highly digitigrade to unguligrade stance just

before toe lift-off. This adds to the greater effective limb length in the

hindlimb compared to the lower hyperextension angles in the forelimb. Further

indicators for digitigrady are the dorsoventrally flattened cross-sections of

the metatarsal shafts and the lack of proximal-distal arching in the metatarsus,

both indicating low craniocaudal bending moments.

Poses of the entire skeleton

In the following, both bipedal and quadrupedal poses are described, and their

biomechanical implications are addressed.

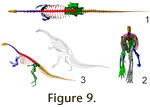

B ipedal poses. For a bipedal, theropod-like posture, the

hindlimb of Plateosaurus can be placed in accordance with the evidence on

bone loading derived from longbone curvature and cross sections. The femur is

inclined forward at a protraction angle around 20°. The knee is flexed, and the

tibia and fibula inclined slightly posteriorly. The ankle is also slightly

flexed, placing the metatarsus in a vertical or, more probably, sub-vertical

position at midstance (Figures 1.2,

9.1, 9.2,

Video 1). ipedal poses. For a bipedal, theropod-like posture, the

hindlimb of Plateosaurus can be placed in accordance with the evidence on

bone loading derived from longbone curvature and cross sections. The femur is

inclined forward at a protraction angle around 20°. The knee is flexed, and the

tibia and fibula inclined slightly posteriorly. The ankle is also slightly

flexed, placing the metatarsus in a vertical or, more probably, sub-vertical

position at midstance (Figures 1.2,

9.1, 9.2,

Video 1).

Any bipedal posture is only feasible if the COM is supported by the hindfeet. If

the COM rests close to the hips, the exact orientation of the vertebral column

does not matter. If it is placed further forward, so that the hindlimb does not

support it when the back is in a subhorizontal position, the simplest way to

change the anteroposterior position of the COM is to tilt the vertebral column.

The steeper it is placed, the further back the COM moves.

Huene 1928 suggested a

fairly steep position for rapid locomotion (Figure 9.3), similar to the then

prevailing view of Iguanodon (Dollo 1893) and other bipedal dinosaurs.

Later, a paradigm shift lead to almost universal agreement that most dinosaurs

had subhorizontal backs when walking bipedally (e.g.,

Norman 1980;

Bakker 1986;

Paul 1987). The main reason for the latter posture is the far greater femur

retraction range that it allows compared to a more upright posture.

Plateosaurus can be placed bipedally in either position (Figures 1.2,

9.1-3), but the more upright posture limits locomotion speed significantly. An

upwards angle of at least 45° is required for the long axis of the sacrum to

create a significant backwards shift of the COM. However, already at 30° (Figure

9.3), the femur must be retracted to the level of the ischia, so that only very

small steps are possible. Also, if the COM lies so far posteriorly that this

pose (30° upwards rotation) is balanced, rotating the body around the hips

requires very little energy, due to the small moment arm. Therefore, it seems

more reasonable to assume that a bipedal Plateosaurus might feed with a

steeply inclined vertebral column (Figure

9.3), but use a subhorizontal posture

(Figure 1.2) for locomotion.

In a bipedal pose with a subhorizontal back, the neutral pose of the vertebral

column leads to a head position above the highest point of the back. The animal

can thus cover a 360° arc by a small neck motion alone, i.e., there is no blind

area. In order to bring the snout to the ground, e.g. for drinking, a slight

increase in hindlimb flexion and moderate ventriflexion of the anterior two

thirds of the thoracic vertebral column and maximum ventriflexion of the neck is

sufficient (Mallison in press, contra

Huene 1928), but even a slight seesaw

motion that rotates the anterior body down (as suggested to be necessary by

Huene [1928]) does not inhibit rapid flight. In contrast, to bring the hands to

the ground for grasping requires significant flexion of the hindlimbs, with

greatly increases joint torques required to sustain the pose. Essentially, the

animal must kneel or squat down when manipulating objects at ground level for a

prolonged time, or use a front limb for support. Dual-handed grasping is then

impossible. Rainforth's (2003) redescription of the ichnofossil Otozoum

pointed out that one track shows a bipedal animal, potentially a prosauropod,

using both hands, palms facing medially, to support itself, probably while

squatting down.

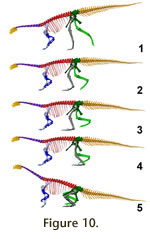

Quadrupedal poses. In a quadrupedal pose the forelimbs must be

able to take strides of a significant length. If a stride length of only 0.4 m

is to be possible, the height of the glenoid above the ground when placing the

manus on the ground can not be more than 0.6 m. Due to this extremely short

forelimb length, the vertebral column slope downwards so that the 1stdorsal

– 2ndsacral line slopes by 19° for a digitigrade

Figure 10.1), and 9°

for a semi-plantigrade model (Figure 10.2). In a fully plantigrade (FVP) model,

whether with a strongly protracted or nearly vertical femur position, the head

is at or slightly above the same height as the sacrum (Figure 10.3-4). These

postures bring the manus on the ground without introducing strong ventriflexion

in the dorsal series, and retain room for femur excursions during locomotion.

The effective forelimb/hindlimb length ratios (i.e., height of glenoid divided

by height of acetabulum in midstance pose) are 0.45 for the digitigrade, 0.54

for the semi-plantigrade, and 0.59 for the plantigrade model. In all these

positions the motion of the hindlimb is significantly limited compared to a

bipedal posture. In the digitigrade model, the femur can be protracted roughly

20° less than in a bipedal pose, reducing stride length. In the semi- and

plantigrade models, limb protraction requires extreme flexion of the ankle while

the free limb passes the supporting limb, due to the great length of the pes

compared to the tibia. In such a pose femur retraction cannot be the main

component of protraction unless the animal uses a sprawling posture, in direct

contradiction to the osteological evidence (see

Gatesy 1990). Quadrupedal poses. In a quadrupedal pose the forelimbs must be

able to take strides of a significant length. If a stride length of only 0.4 m

is to be possible, the height of the glenoid above the ground when placing the

manus on the ground can not be more than 0.6 m. Due to this extremely short

forelimb length, the vertebral column slope downwards so that the 1stdorsal

– 2ndsacral line slopes by 19° for a digitigrade

Figure 10.1), and 9°

for a semi-plantigrade model (Figure 10.2). In a fully plantigrade (FVP) model,

whether with a strongly protracted or nearly vertical femur position, the head

is at or slightly above the same height as the sacrum (Figure 10.3-4). These

postures bring the manus on the ground without introducing strong ventriflexion

in the dorsal series, and retain room for femur excursions during locomotion.

The effective forelimb/hindlimb length ratios (i.e., height of glenoid divided

by height of acetabulum in midstance pose) are 0.45 for the digitigrade, 0.54

for the semi-plantigrade, and 0.59 for the plantigrade model. In all these

positions the motion of the hindlimb is significantly limited compared to a

bipedal posture. In the digitigrade model, the femur can be protracted roughly

20° less than in a bipedal pose, reducing stride length. In the semi- and

plantigrade models, limb protraction requires extreme flexion of the ankle while

the free limb passes the supporting limb, due to the great length of the pes

compared to the tibia. In such a pose femur retraction cannot be the main

component of protraction unless the animal uses a sprawling posture, in direct

contradiction to the osteological evidence (see

Gatesy 1990).

Subequal fore and hind limb lengths cannot be created, even with a pronated

manus and parasagittal forelimbs, as it requires femur protraction to beyond the

pubes at midstance, and to subhorizontal for limb protraction (Figure 10.5,

Video 3). Note that in this position the height of the glenoid was artificially

increased to 0.7 m by using a standing instead of a walking pose in the

forelimb. This position does not allow proper walking at all, as it limits

stride length to 0.2 m. Subequal fore and hind limb lengths cannot be created, even with a pronated

manus and parasagittal forelimbs, as it requires femur protraction to beyond the

pubes at midstance, and to subhorizontal for limb protraction (Figure 10.5,

Video 3). Note that in this position the height of the glenoid was artificially

increased to 0.7 m by using a standing instead of a walking pose in the

forelimb. This position does not allow proper walking at all, as it limits

stride length to 0.2 m.

However, all these poses were created with a pronated manus. If the forelimb is

placed in correct articulation with regards to the wrist and elbow, strong

humerus abduction is required to turn to palm ventrally. This would essentially

create a sprawling pose. However, it is not possible to rotate the humerus

around its long axis to create a subvertical antebrachium, so that the animal

would touch the ground with its ribcage. If the hindlimbs are placed in a

sprawling position (following Fraas 1912; contra

Huene 1926,

1928;

Gatesy 1990;

Christian

and Preuschoft 1996;

Christian et al. 1996), the femora must be disarticulated

from the pelvis, and the tibia and fibula must be disarticulated from the distal

femoral condyles. Alternatively to a sprawling pose, Plateosarus might

have walked on non-pronated hands, but

Bonnan and Senter (2007) show clearly

that the required adaptations are missing.

A potentially negative effect of the only quadrupedal poses in which the

hindlimbs can be moved in a realistic gait cycle (hindlimbs digitigrade,

Figure

10.1) is the forwardly inclined vertebral column combined with the low shoulder

height. At neutral articulation of the neck, the view the animal can see is

quite limited. A blind angle extends posteriorly, and lateral excursions of the

neck to 'check six' result in a large blind area on the contralateral side.

Extreme dorsiflexion of the neck is required to bring the head to a sufficient

height so that a 360° view is possible. While possibly feasible when feeding,

during rapid locomotion such a neck position carries a high risk, because all

articulations are at their bony stops. Therefore, even slight impulses, e.g.,

from stumbling, can lead to serious injury. Extant animals appear to carry their

necks close to neutral articulation during rapid locomotion (Christian and Dzemski 2007), potentially because of this risk. For Plateosaurus,

running in a quadrupedal posture carrying the neck near neutral articulation

leads to a head height below hip height, close enough to the ground that a

misstep in the forelimbs leads to an impact on the ground.

A further potential disadvantage is the maximum possible head height, and thus

size of the feeding envelope. The base of the neck is at two thirds the height

of a bipedal pose (0.99 m compared to 1.49 m). Additionally, in a bipedal pose

the animal can tilt the body up to increase shoulder and thus feeding height

(Figure 9.3). While Plateosaurus could theoretically be envisaged as an

obligate quadruped that uses quadrupedal gaits for slow locomotion, then gets up

into a bipedal pose to feed, and then back down again into a quadrupedal stance

for locomotion, this makes sense only if there are bipedal stances suitable for

feeding but not for locomotion. These could only be postures with a steeply

inclined vertebral column, akin to a rearing elephant. However, as shown above,

there are no bipedal poses that do not allow locomotion.

Body mass

The CAD model of Plateosaurus based on GPIT1 has a total volume of 740 l.

There are no indications of air sacs invading bone to form post-cervical

pneumatic cavities in Plateosaurus or other prosauropods (Wedel 2007),

but the dorsal vertebrae show shallow troughs on the centra. In combination with

the ability to breathe through rib motion, this indicates that prosauropods

probably possessed pulmonary air sacs. An extant phylogenetic bracket (EPB)

approach (Witmer 1995) confirms this: both theropods and sauropods had (and

have) bird-like lungs (Perry and Reuter 1999;

Wedel 2005,

2007;

O'Connor and Claessens 2005), as

indicated by the extensive pneumaticity of their skeletons. Birds have densities

as low as 0.73 kg/l (Hazlehurst and Rayner 1992), and sauropod density is

therefore probably best assumed to be about 0.8 kg/l or even lower (Wedel 2005).

Crocodiles have lungs that, albeit simpler in structure than those of birds, are

interpreted as a preadaptation for the formation of true air sacs and a

unidirectional lung (Perry 1998;

Farmer and Sanders 2010). Therefore, it is most

parsimonious to assume the existence of small pulmonary air sacs in

Plateosaurus, even though they did not invade bones and thus left no clear

marks on the preserved parts of the animals. Rib motion probably was the main

mode of lung ventilation in Plateosaurus, because the architecture of the

costovertebral articulations (dual headed hinge joints) is the same as is

generally the case in saurischians (basal Saurischia:

Langer 2004;Tyrannosaurus:

Hirasawa 2009), and the air exchange volume can be estimated at a value typical

for birds (Mallison in press). The air sacs may have been large, but in the

absence of solid evidence (skeletal pneumaticity) for a large size they must be

assumed to have been so small that the overall density can be modeled on that of

extant terrestrial vertebrates. As a consequence, the average density should

cautiously be

assumed at a value between 0.9 kg/l and 1.0 kg/l.

Additionally, density is not uniform across the entire animal, and various body

parts were accordingly given values that reflect the relative abundance of bone,

flesh, intestines, and air volumes in them. Skull, tail, limbs, and the pelvic

region are assumed to be heavier than water (d = 1.05 kg/l to 1.1 kg/l), while

the neck and anterior trunk region are significantly lighter (d = 0.7 kg/l).

This basic model has an average density of 0.94 kg/l and a total weight of 693

kg. Variations of the density of model parts to account for different soft

tissue amounts, details of which are given in

Table 1, result in average

densities between 0.89 kg/l and 1.13 kg/l. The basic model has a very posteriorly placed COM, so most variations were designed to move the COM

forward. This was achieved by reducing the mass of the tail and posterior trunk,

and/or increasing the mass of neck and anterior trunk. However, one variant was

produced in which the limbs were given higher density, too, although this partly

cancels the effect that a heavier neck and anterior body have on shifting the

center of mass. Total mass varies between 600 kg and 838 kg. Scaled to the size

of the largest and smallest known individuals (total length 10 m and 4.8 m,

Sander and Klein 2005) of Plateosaurus, the basic model gives a weight

range from 476 kg to roughly 4300 kg for an average density of 0.89 kg/l.

Position of the center of mass (COM)

In the basic model, the COM rests 0.23 m in front of and 0.16 m below the

acetabulum in a bipedal standing pose. The mass variations result at most in an

anterior shift by 0.06 m to 0.29 m (Table 1). The dorsoventral shift is

negligible.

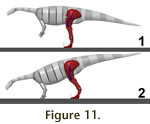

Bipedal poses. In the bipedal poses created on the basis of a

best fit of the skeletal elements, in all but one the COM rests comfortably

above the support area (Figure 11.1). This is true in both the digitigrade and

the semi-plantigrade pose, and requires only modest femur protraction (maximum

value 20° from vertical, in combination with a fully digitigrade stance and a

metatarsus inclination of 65° from horizontal). For the most front-heavy mass

variation at full digitigrady the COM plots just in front of the longest digit.

Femur protraction to 25° (+5° compared to the basic model) brings the support

area under the COM in this model.

Quadrupedal poses. In all models with an inclined femur

the COM plots in the support area of the hind foot or at its anterior edge,

unless the lower hindlimb is placed at an unrealistic strong posterior

inclination (as in Figure 10.4). If the hind limb is posed as deemed

anatomically correct here, with a protracted femur, limited knee and ankle

flexion and fully digitigrade, the ratio of effective limb lengths is 0.45, and

the hindlimb carries between 90% and all of the weight. Unrealistically flexing

the knee so that the tibia is strongly inclined leads to a maximum of 35% of the

weight supported on the forelimbs, albeit with a low effective limb length ratio

of 0.52. Increased limb flexion, which results in less massively unequal limb

lengths, moves the support area forward, due to increases in femur protraction

and ankle flexion. In fact, even absurdly light-tailed versions of the model

with a significantly inflated pectoral region and neck have a COM plotting

solidly within the area of the hindfoot in midstance at effective limb length

ratios between 0.7 and 1. Subequal fore and hind limb lengths in a sprawling

position place up to 40% of the weight on the forelimbs but are osteologically

impossible.

Models with a vertical femur position place more weight on the forelimbs, by

shifting the support point of the hind limbs posteriorly. However, they either

require a strongly inclined position of the lower hindlimb, which creates large

bending moments because of the long moment arm of the COM and high torques in

the knee and ankle joints, or cause an extreme difference in limb length. In

extant animals with parasagittal limbs, the hindfoot is almost always placed

under the hip joint, or close to such a position. The Plateosaurus models

with a vertical femur and strong limb flexion, however, result in a foot

position far behind the acetabulum. Such a posture causes extreme flexing

moments in the knee and ankle, and can thus be dismissed as unrealistic,

especially considering the short moment arms of the extensor muscles of the

ankle and knee. The alternative pose, with a steeply placed lower hindlimb (low

limb flexion), causes similarly low limb length ratios as those models with an

inclined femur and a slightly flexed hind limb. At most, using the unreasonable

mass distribution of the most front-heavy model (d = 1.13 kg/l), the forelimbs

carry about 41% of the body weight (Figure 11.2), with a limb length ratio of

0.45. Note, however, that for this hindlimb posture the acetabulum is not above,

but far in front of the point of support, and the hind limb thus permanently

subjected to large bending moments. Models with a vertical femur position place more weight on the forelimbs, by

shifting the support point of the hind limbs posteriorly. However, they either

require a strongly inclined position of the lower hindlimb, which creates large

bending moments because of the long moment arm of the COM and high torques in

the knee and ankle joints, or cause an extreme difference in limb length. In

extant animals with parasagittal limbs, the hindfoot is almost always placed

under the hip joint, or close to such a position. The Plateosaurus models

with a vertical femur and strong limb flexion, however, result in a foot

position far behind the acetabulum. Such a posture causes extreme flexing

moments in the knee and ankle, and can thus be dismissed as unrealistic,

especially considering the short moment arms of the extensor muscles of the

ankle and knee. The alternative pose, with a steeply placed lower hindlimb (low

limb flexion), causes similarly low limb length ratios as those models with an

inclined femur and a slightly flexed hind limb. At most, using the unreasonable

mass distribution of the most front-heavy model (d = 1.13 kg/l), the forelimbs

carry about 41% of the body weight (Figure 11.2), with a limb length ratio of

0.45. Note, however, that for this hindlimb posture the acetabulum is not above,

but far in front of the point of support, and the hind limb thus permanently

subjected to large bending moments.

In all quadrupedal poses that do not shift the pectoral girdle to an absurdly

low position on the ribcage, the COM lies significantly higher than the glenoid

(e.g., at 1.5 times the height in the model shown in

Figure 11.2). This means

that the stability of the anterior body part when supported by only one forelimb

is reduced compared to the pattern seen in nearly all extant quadrupeds, in

which the limb articulation with the trunk rests higher than or roughly at the

level of the COM.

Stability of slow gaits. The extremely posterior position of

the COM has consequences for the stability of even slow gaits. Slow locomotion

means that the body, due to its low moment of inertia, has ample time to react

to small lateral imbalances. Unless one is balanced well, much energy is

expended correcting the balance instead of moving forward. When walking slowly

and bipedally, the body must sway laterally or the feet must

be placed in front of each other, on the track midline, so that the COM passes

exactly over the support area. These two solutions, or any combination of them,

require strong limb adduction to bring the foot under the COM. A more

longitudinal support area, such as a plantigrade instead of a digitigrade foot,

or quadrupedal instead of bipedal gaits, reduce the risk of toppling as well as

the need to adduct the hindlimbs fully. A wider track is possible, creating a

wide support triangle (Henderson 2006). To be effective, the quadrupedal posture

should thus increase both the width and the length of the support area compared

to a bipedal pose. The latter, a minor factor, is obviously the case in

practically any quadruped, but the former relies on allowing a wider track in

the forelimbs and hindlimbs for creating a wide support triangle when any one

limb is lifted.

In Plateosaurus this is not the case in any osteologically possible

quadrupedal pose, even assuming manus pronation, as is best shown by a test of

the balance in a three-point support pose. If a hindfoot is lifted off the

ground in a CAE model, using the most front-heavy mass variant, in a standing

pose with only 10° femoral abduction in both limbs, the animal tends to topple

caudolaterally, because the COM lies behind the support triangle formed by the

forefeet and the remaining hindfoot. The supporting hindlimb must be adducted to

nearly the same angle as in a biped to avoid this. Therefore, a quadrupedal pose

does not offer a significant advantage with regard to stability, because an

accidental imbalance in the supporting hindlimb is as dangerous as in a bipedal

stance. A detailed discussion of walking cycles in Plateosaurus is beyond

the scope of this paper.

Potential trackways. The virtual skeleton cannot be placed in a

quadrupedal pose that allows normal locomotion. Therefore, none of the

quadrupedal trackways assigned to prosauropods, such as Tetrasauropus

unguiferus (Ellenberger 1972) or Navahopus falcipollex (Baird 1980)

were created by a plateosaurid. In contrast, the skeleton can be placed to

conform to the ichnofossil Otozoum moodii (Hitchcock 1847,

Rainforth 2003), contra

Farlow (1992).

Porchetti and Nicosia (2007) fitted the

scaled-down pes of Plateosaurus into the track of Tetrasauropus in

a plantigrade stance. As shown, this posture is highly unlikely for

Plateosaurus.

|