| |

RESULTS

Global Averages of Temperature and Sea Ice Cover

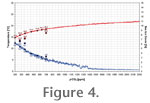

Figure

4 illustrates that in the Miocene and present-day simulations, the global

temperature increases and the global sea ice cover decreases with an increased

atmospheric carbon dioxide. The global temperature of the Tortonian runs is

generally higher than in the present-day simulations (if CO2 is the

same in CTRL and TORT). Accordingly, the sea ice cover of TORT-200 to TORT-INC

is also lower than in CTRL-280 to CTRL-700. With increasing CO2,

the global temperature and sea ice cover of TORT-INC follows quite well the

distribution of the other runs TORT-200 to TORT-700. Hence, the CO2

increase of +1 ppm is small enough to keep TORT-INC close to the equilibriums

of TORT-200 to TORT-700. Figure

4 illustrates that in the Miocene and present-day simulations, the global

temperature increases and the global sea ice cover decreases with an increased

atmospheric carbon dioxide. The global temperature of the Tortonian runs is

generally higher than in the present-day simulations (if CO2 is the

same in CTRL and TORT). Accordingly, the sea ice cover of TORT-200 to TORT-INC

is also lower than in CTRL-280 to CTRL-700. With increasing CO2,

the global temperature and sea ice cover of TORT-INC follows quite well the

distribution of the other runs TORT-200 to TORT-700. Hence, the CO2

increase of +1 ppm is small enough to keep TORT-INC close to the equilibriums

of TORT-200 to TORT-700.

Comparing CTRL-360 and CTRL-700 vs. CTRL-280 and the Tortonian

runs, the response on an increased pCO2 is more pronounced

in the present-day simulations. The temperature difference between CTRL-700

and CTRL-360 is +2.5°C, whereas it is +1.9°C between TORT-700 and TORT-360.

Sea ice cover is reduced by –2.9% (CTRL-700 minus CTRL-360) and by –2.1%

(TORT-700 minus TORT-360), respectively. Hence, the weaker response to a CO2

increase is explained by the generally lower amount of sea ice in the Miocene

experiments, i.e., the ice-albedo feedback is weaker.

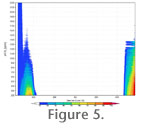

Figure

5 illustrates the zonal average sea ice cover of TORT-INC with respect to

CO2. A critical threshold for the Arctic ice cover is around 1,250

ppm. At this level, the northern sea ice entirely vanishes for the first time,

but it sensitively responds on climate fluctuations. If there is a small

deviation (climate variability), ice-free conditions cannot be maintained.

With an atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of about 1,400 ppm, the

Northern Hemisphere is permanently ice-free in TORT-INC. The sea ice cover on

the Southern Hemisphere is generally maintained. However, only a few small

fractions of sea ice remain if pCO2 is higher than about

1,500 ppm. Figure

5 illustrates the zonal average sea ice cover of TORT-INC with respect to

CO2. A critical threshold for the Arctic ice cover is around 1,250

ppm. At this level, the northern sea ice entirely vanishes for the first time,

but it sensitively responds on climate fluctuations. If there is a small

deviation (climate variability), ice-free conditions cannot be maintained.

With an atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of about 1,400 ppm, the

Northern Hemisphere is permanently ice-free in TORT-INC. The sea ice cover on

the Southern Hemisphere is generally maintained. However, only a few small

fractions of sea ice remain if pCO2 is higher than about

1,500 ppm.

Zonal Average Temperatures

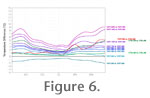

Figure

6 shows the zonal average temperatures of the simulations wherein the

Miocene experiments are represented against TORT-280 and the present-day runs

and TORT-280 against CTRL-280, respectively. TORT-280 is much warmer than

CTRL-280 at around 30°N (+4°C) and farther to the northern high latitudes

(+5°C). Close to the equator, CTRL-280 and TORT-280 do not differ much (less

than +1°C). Thus, TORT-280 represents a weaker-than-present meridional

temperature gradient of –4°C. The meridional gradient in TORT-200 is less

pronounced than in TORT-280, but it is still weaker than in CTRL-280. With

increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the low to high latitudes get

successively warmer, but polar warming is much more intense. In TORT-INC at

2,000 ppm, the high latitudes heat up by +9°C as compared to TORT-280, and

tropical latitudes are +3.5°C warmer. Thus, the temperature difference between

pole and equator is –5.5°C lower than in TORT-280. The successive reduction of

the meridional temperature gradient is a result of the sea ice-albedo feedback

(cf. Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The temperature difference

between TORT-2000 (i.e., TORT-INC at 2000 ppm) and TORT-1500 is generally less

than for TORT-1500 vs. TORT-1000. The weaker response is due to the fact that

northern sea ice vanishes at around 1,400 ppm (Figure

5). Figure

6 shows the zonal average temperatures of the simulations wherein the

Miocene experiments are represented against TORT-280 and the present-day runs

and TORT-280 against CTRL-280, respectively. TORT-280 is much warmer than

CTRL-280 at around 30°N (+4°C) and farther to the northern high latitudes

(+5°C). Close to the equator, CTRL-280 and TORT-280 do not differ much (less

than +1°C). Thus, TORT-280 represents a weaker-than-present meridional

temperature gradient of –4°C. The meridional gradient in TORT-200 is less

pronounced than in TORT-280, but it is still weaker than in CTRL-280. With

increasing carbon dioxide in the atmosphere, the low to high latitudes get

successively warmer, but polar warming is much more intense. In TORT-INC at

2,000 ppm, the high latitudes heat up by +9°C as compared to TORT-280, and

tropical latitudes are +3.5°C warmer. Thus, the temperature difference between

pole and equator is –5.5°C lower than in TORT-280. The successive reduction of

the meridional temperature gradient is a result of the sea ice-albedo feedback

(cf. Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The temperature difference

between TORT-2000 (i.e., TORT-INC at 2000 ppm) and TORT-1500 is generally less

than for TORT-1500 vs. TORT-1000. The weaker response is due to the fact that

northern sea ice vanishes at around 1,400 ppm (Figure

5).

Between CTRL-360 and CTRL-280, there are just minor

differences of less than +1°C, which is similarly seen from TORT-360 as

compared to TORT-280. However, CTRL-700 vs. CTRL-280 as compared to CTRL-360

vs. CTRL-280 demonstrates a more amplified polar warming than TORT-700 and

TORT-360 vs. TORT-280, respectively. The CO2 doubling from 360 ppm

to 700 ppm leads to a polar warming of +4°C under present-day conditions,

whereas it is only +3°C in the Miocene. In lower latitudes, the response to

the CO2 increase is about the same. Thus, the sea ice-albedo

feedback tends to be weaker under Miocene boundary conditions than using

present-day conditions (cf. Figure 4).

Spatial Temperature Anomalies

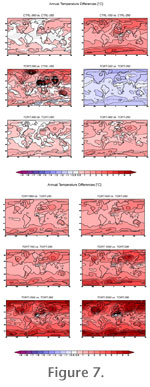

The

spatial distribution of mean annual temperature differences and the sea ice

margin between our simulations are shown in

Figure 7. The increase of CO2

leads to a generally more pronounced warming in the present-day experiments as

compared to the Miocene runs (_blank). For CTRL-280 to CTRL-700, the ice

volume is greater than in TORT-200 to TORT-2000 (cf. sec. 3.1 and 3.2).

Therefore, the ice-albedo feedback is more intense under present-day

conditions. Moreover, the Paratethys dampens the general warming trend due to

enhanced CO2 in the Miocene simulations. In TORT-200 as compared to

TORT-280, the cooling because of a decreased CO2 occurs primarily

in higher latitudes. This is a contrast to the other Tortonian runs.

Generally, interior parts of the continents become warmer when CO2

increases. Not until a high concentration of CO2 and ice-free

conditions are reached, polar warming is in the same order of magnitude as

over the continental areas. In Central Africa, temperatures in the Tortonian

runs remain more or less the same when increasing CO2. An

intensified evapotranspiration (evaporative cooling) dampens the temperature

increase due to the greenhouse effect. The

spatial distribution of mean annual temperature differences and the sea ice

margin between our simulations are shown in

Figure 7. The increase of CO2

leads to a generally more pronounced warming in the present-day experiments as

compared to the Miocene runs (_blank). For CTRL-280 to CTRL-700, the ice

volume is greater than in TORT-200 to TORT-2000 (cf. sec. 3.1 and 3.2).

Therefore, the ice-albedo feedback is more intense under present-day

conditions. Moreover, the Paratethys dampens the general warming trend due to

enhanced CO2 in the Miocene simulations. In TORT-200 as compared to

TORT-280, the cooling because of a decreased CO2 occurs primarily

in higher latitudes. This is a contrast to the other Tortonian runs.

Generally, interior parts of the continents become warmer when CO2

increases. Not until a high concentration of CO2 and ice-free

conditions are reached, polar warming is in the same order of magnitude as

over the continental areas. In Central Africa, temperatures in the Tortonian

runs remain more or less the same when increasing CO2. An

intensified evapotranspiration (evaporative cooling) dampens the temperature

increase due to the greenhouse effect.

The Sensitivity Experiments vs. Quantitative Terrestrial Proxy Data

Steppuhn et al. (2007)

established a method to compare Late Miocene model experiments with

quantitative terrestrial proxy data. We now use basically the same method to

test how consistent the mean annual temperatures (MAT) of the different Late

Miocene CO2 scenarios are as compared to the fossil record. The

main data set of terrestrial proxy data is given in

Steppuhn et al. (2007). All data for

mean annual temperature (MAT) are based on quantitative climate analyses of

fossil plant remains from the Tortonian stage (early Late Miocene, ~ 11 to 7

Ma). For most of the data, the Coexistence Approach (Mosbrugger

and Utescher 1997) was applied on micro- (pollen and spores) and

macro-botanical (leaves, fruits, and seeds) fossils. The results of this

method are 'coexistence intervals,' which express the minimum-maximum range of

temperature at which a maximum number of taxa of a given flora can exist.

Relying mainly on one reconstruction method reduces the impact of

methodological inconsistencies. However, such data are not yet available for

North America. Therefore, we also included some published quantitative climate

data based on the CLAMP technique (Wolfe

1993), which has proven to be a reliable method especially for climate

quantification on the American continent (cf.

Wolfe 1995,

1999).

Because

such data usually do not include a minimum-maximum range of temperature, a

standard range of uncertainty of ±1 °C was assumed for the

data-model-comparison. We completed the

Steppuhn et al. (2007) data set with additional climate information from

Wolfe et al. (1997) and new data from the NECLIME program (see

http://www.neclime.de) published in

Akgün et al. (2007),

Bruch et al. (2007) and

Utescher et al. (2007). The actual

data set used in this study now comprises 78 localities. Because most of the

proxy data represent a climatic range from a minimum to a maximum mean annual

temperature at a locality, Steppuhn et al.

(2007) constructed a similar MAT range from the minimum and maximum mean

annual temperature of their 10-year-model integrations at the specific grid

points. In case of an overlap of both climate intervals, model results and

proxy data are defined to be consistent (i.e., the temperature difference is

equal zero); in case both intervals do not overlap, the smallest distance

between them is defined to be a measure for the inconsistency. We slightly

modify the validation method of Steppuhn

et al. (2007) because results of TORT-1000, TORT-1500, and TORT-2000 do

not represent a time series over 10 years. Instead of creating temperature

intervals from our simulations, we use "point" data. For TORT-1000 to

TORT-2000, the point data are simply the mean annual temperatures of the years

900, 1400, and 1900, respectively. For TORT-200 to TORT-700, the point data

are the mean annual temperatures averaged over the last 10 years of the model

integrations. Except of this difference, the validation method follows the

same principle as before (Steppuhn et al.

2007). Table 2 summarises the

overall agreement of the Tortonian simulations with proxy data. In

Figure 8, the temperature differences

between the simulations and proxy data are mapped for all localities. Because

such data usually do not include a minimum-maximum range of temperature, a

standard range of uncertainty of ±1 °C was assumed for the

data-model-comparison. We completed the

Steppuhn et al. (2007) data set with additional climate information from

Wolfe et al. (1997) and new data from the NECLIME program (see

http://www.neclime.de) published in

Akgün et al. (2007),

Bruch et al. (2007) and

Utescher et al. (2007). The actual

data set used in this study now comprises 78 localities. Because most of the

proxy data represent a climatic range from a minimum to a maximum mean annual

temperature at a locality, Steppuhn et al.

(2007) constructed a similar MAT range from the minimum and maximum mean

annual temperature of their 10-year-model integrations at the specific grid

points. In case of an overlap of both climate intervals, model results and

proxy data are defined to be consistent (i.e., the temperature difference is

equal zero); in case both intervals do not overlap, the smallest distance

between them is defined to be a measure for the inconsistency. We slightly

modify the validation method of Steppuhn

et al. (2007) because results of TORT-1000, TORT-1500, and TORT-2000 do

not represent a time series over 10 years. Instead of creating temperature

intervals from our simulations, we use "point" data. For TORT-1000 to

TORT-2000, the point data are simply the mean annual temperatures of the years

900, 1400, and 1900, respectively. For TORT-200 to TORT-700, the point data

are the mean annual temperatures averaged over the last 10 years of the model

integrations. Except of this difference, the validation method follows the

same principle as before (Steppuhn et al.

2007). Table 2 summarises the

overall agreement of the Tortonian simulations with proxy data. In

Figure 8, the temperature differences

between the simulations and proxy data are mapped for all localities.

On the global scale (Table

2), the experiment TORT-280 fits best with terrestrial proxy data, but

also TORT-200, TORT-360, and TORT-460 give more or less consistent results.

Discrepancies of TORT-200 to TORT-460 are within ±1°C. These deviations to the

fossil record are quite acceptable. As one might expect, TORT-2000

demonstrates the worst overall consistency to proxy data and is globally much

too warm.

Figure 8 shows details

of the comparison of model results and proxy data. TORT-200 and TORT-280

globally demonstrate the best agreement to proxy data, but they are

systematically too cool in higher latitudes. TORT-360 and TORT-460 indicate a

better agreement in higher latitudes. However, both runs tend to be slightly

too warm in the mid-latitudes, particularly in Europe. At the expense of

heating up lower and mid-latitudes, TORT-560 to TORT-2000 are continuously

more consistent to high-latitude proxy data.

Figure 8 illustrates that TORT-360 to

TORT-560 basically agree best with proxy data. This agreement seems to be in

contrast to Table 2, but one has to

keep in mind that the spatial distribution of proxy data is highly

concentrated on Europe. Consequently, discrepancies in this region are

over-weighted as compared to others. Our results support that pCO2

in the Late Miocene is within the range of 360 to 560 ppm. |