Comparative Stress Magnitudes

Collective data. For all jaws scaled to the same linear dimensions, mean Von Mises stress was greater at all transect points in the extant ruminants than hindgut fermenters (only marginally so at the centre of the jaw, where the neutral axis of bending occurs, as would be expected

[Table 2]).

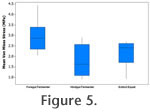

Mean stress across the mid-tooth row transect for all extant hindgut fermenters was 1.78 MPa (n = 6), while ruminants showed generally higher values with a mean stress of 2.93 MPa (n=11) (Table 2,

Figure 5). This collective difference in stress values is seen regardless of size or dietary habits (e.g., grazer versus browser). Extant hindgut fermenters showed a smaller range of mean stress values (0.91 MPa for Tapiris terrestris to 2.92 MPa for Equus burchellii, SD = 0.82) than ruminants (2.05 MPa for Tragulus javanicus to 4.44 MPa for Giraffa camelopardalis, SD = 0.71). Mean Von Mises stress values for all extinct equid species was 2.18 MPa (n = 8), ranging from 0.93 MPa (Hyracotherium) to 2.47 MPa (Mesohippus sp.). The stress values in all hindgut fermenters (extant and extinct) were lower than the mean stress values for ruminants. Our results show that there is little overlap between mean stress for ruminants and hindgut fermenters (Figure 5), but this observation may be influenced by sample size. Mean stress across the mid-tooth row transect for all extant hindgut fermenters was 1.78 MPa (n = 6), while ruminants showed generally higher values with a mean stress of 2.93 MPa (n=11) (Table 2,

Figure 5). This collective difference in stress values is seen regardless of size or dietary habits (e.g., grazer versus browser). Extant hindgut fermenters showed a smaller range of mean stress values (0.91 MPa for Tapiris terrestris to 2.92 MPa for Equus burchellii, SD = 0.82) than ruminants (2.05 MPa for Tragulus javanicus to 4.44 MPa for Giraffa camelopardalis, SD = 0.71). Mean Von Mises stress values for all extinct equid species was 2.18 MPa (n = 8), ranging from 0.93 MPa (Hyracotherium) to 2.47 MPa (Mesohippus sp.). The stress values in all hindgut fermenters (extant and extinct) were lower than the mean stress values for ruminants. Our results show that there is little overlap between mean stress for ruminants and hindgut fermenters (Figure 5), but this observation may be influenced by sample size.

Paired data. Data were paired according to similar body size and feeding behaviour (grazer, mixed feeder or browser; see

Table 1) to remove dietary habit and allometric effects from consideration. Paired t-tests comparing six extant pairings of ruminants and hindgut fermenters (Table 1) revealed a statistically significant difference in mean transect values (p = 0.023).

The extinct species of hindgut fermenters (all equids) were paired with extant ruminants of similar body size and likely similar diet (Table 1). The reason for including these forms was to "fill in the gaps" that no extant hindgut fermenting ungulate occupies today (i.e., small to medium-sized browsers and mixed feeders) to see if the pattern held over the entire range of diets and body sizes. As diet was obviously conjectural in these extinct species, estimated from dental features (hypsodonty index and microwear, as previously discussed), statistical differences in stress between these pairs was analysed separately from the pairings that contained only extant taxa.

Pairings of extant ruminants and extinct equids (Table 1) were compared on an individual basis (Figure 6.2) and showed that the jaws of most extinct equids were more robust than those of the extant ruminants. The exception here was the pairing of Damaliscus lunatus (tsessabe) with the equid

Calippus martini: here the equid showed a mean stress of 2.67, greater than that of the ruminant, with a mean stress of 2.20. Without further sampling it is impossible to know if this figure is significant.

The jaws of the extinct equids showed an average of 24.68% less stress across the transect than their paired extant ruminant, with values ranging from 18.11% less stress (Merychippus sp.) to 60.39% less stress (Hyracotherium sp.). With the exclusion of Damaliscus and

Calippus, the average for all pairs increased to 31.23% (n = 7) lower stress in extinct equids than their extant ruminant pairing. Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric analysis showed borderline insignificance between mean Von Mises stress values between ruminants and extinct hindgut fermenters (p = 0.058). If Damaliscus and

Calippus are excluded, the groups are significantly different (p = 0.019).

|