Bioerosion traces in bones of Cuvieronius hyodon from the Loltún Cave, Yucatán: First evidence of osteophagy by insects in Pleistocene caves of Mexico

Bioerosion traces in bones of Cuvieronius hyodon from the Loltún Cave, Yucatán: First evidence of osteophagy by insects in Pleistocene caves of Mexico

Article number: 28.3.a55

https://doi.org/10.26879/1406

Copyright Paleontological Society, December 2025

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Submission: 17 May 2024. Acceptance: 14 November 2025.

ABSTRACT

This study describes and analyzes the first known case of osteophagy by insects in a continental cave setting from the Pleistocene of Mexico. The material consists of both bone and dental remains of Cuvieronius hyodon collected from layer X of the Lotun Cave, Yucatán, Mexico. The fossil remains expose a series of ovoid and ellipsoidal borings that strongly resembles the morphology and size reported for the ichnospecies Cubiculum ornatus, which has been attributed to pupal chambers of beetles of the family Dermestidae. The presence of these bioerosion traces in gomphother bones provides important information on its postmortem history, and the paleoenvironmental scenario established during the entire taphonomic process.

Roberto Emmanuel Hernández Jasso. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Sección de Antropología Física, Centro INAH-Yucatán. Carretera Mérida-Progreso s/n, kilómetro 6.5, Prolongación Montejo, Colonia Gonzalo Guerrero, C. P. 97310, Mérida, Yucatán, México. Corresponding author. biohdz@yahoo.com

Alberto Blanco Piñón. Colegio de Biología. Escuela Normal Superior “Profr. Moisés Saénz Garza”. Av. Venustiano Carranza s/n. Col. Centro. Monterrey, Nuevo León. México. C.P. 64000 and Museo Histórico Regional de General Bravo. Calle 5 de mayo s/n. Centro. General Bravo, Nuevo León, México. C.P. 67000 alberto.blancop@normalmsg.edu.mx; blanco.abp@gmail.com

Keywords: bioerosion; Cubiculum ornatus; dermestids; Cuvieronius; Loltún Cave; Southeastern Mexico

Final citation: Hernández Jasso, Roberto Emmanuel and Blanco Piñón, Alberto. 2025. Bioerosion traces in bones of Cuvieronius hyodon from the Loltún Cave, Yucatán: First evidence of osteophagy by insects in Pleistocene caves of Mexico. Palaeontologia Electronica, 28(3):a55.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1406

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2025/5727-osteophagy-by-insects

Copyright: December 2025 Paleontological Society.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0), which permits users to copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format, provided it is not used for commercial purposes and the original author and source are credited, with indications if any changes are made.

creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/4.0/

INTRODUCTION

Bioerosion is the destruction of hard substrates resulting from biological activity (Neumann, 1966). Traditionally, bioerosion traces have been classically analyzed to determine and understand the nature of the producer. Furthermore, the bone-modification features provide critical insights into the postmortem histories of vertebrate fossil assemblages (Roberts et al., 2007). In recent years, studies of bioerosion traces in fossil bones have been used as an important tool not only for deciphering aspects related to the identification of producer organism, but also for getting valuable information on taphonomy, paleoclimate, and paleoecology (e.g., Cruickshank, 1986; Rogers, 1992; Currie and Jacobsen, 1995; Martin and West, 1995; Hasiotis et al., 1999; Bader et al., 2009; Saneyoshi et al., 2011; Gianechini and De Valais, 2015; Serrano-Brañas et al., 2018; Venegas-Gómez et al., 2024).

One of the most important groups involved in vertebrate decay in continental environments are the insects. Along with other carrion invertebrates, they play a critical role in the decomposition of soft tissues and, to a lesser degree, skeletal material (Campobasso et al., 2001; McHugh et al., 2020). Insects are the main macro-bioeroders that modify bones (e.g., osteophagous, and necrophagous taxa) and can leave distinctive traces on bone surfaces, which are relatively rare both in fossil and the present-day record (West and Martin, 2002; West and Hasiotis, 2007; Pirrone et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2015). Although taxonomic identification of osteophagous organisms to species level can be difficult through their traces, bioerosion features (often assigned to ichnospecies) represent a rich source of biological information concerning the general type and the diversity of the trace producers (Bertling et al., 2006), as well as the diversity of processes that involves the decomposer during the decay.

The oldest confirmed evidence of osteophagy produced by terrestrial invertebrates is represented by bioerosive structures in bone remains produced by the dermestid Cubiculum inornatus, from the Middle Triassic Santa María Supersequence in Brazil (Paes-Neto et al., 2016). Later, Cunha et al. (2023) noticed bioerosion traces in rhynchosaur bones from the Upper Triassic of Brazil, also from the Santa María Supersequence.

Fossil record of bioerosion by insects in bones increases significantly in Upper Jurassic (Hasiotis et al., 1999; Chin and Bishop, 2006; Britt et al., 2008; Bader et al., 2009; Augustin et al., 2021) and Cretaceous rocks (Rogers, 1992; Paik, 2000; Nolte et al., 2004; Roberts et al., 2007; Pirrone et al., 2014; Gianechini and De Valais, 2015; Serrano-Bañas et al., 2018; Venegas-Gómez et al., 2024). Finally, the most abundant records come from the Neogene (Dominato et al., 2009, 2010; Odes et al., 2017; Perea et al., 2020; Zonneveld et al., 2024), including bone remains of Australopithecus specimens (Odes et al., 2017). In Mexico, the only two known cases of bioeroded skeletal remains produced by insects is represented by bones of hadrosaur dinosaurs from the Upper Cretaceous Cerro del Pueblo Formation (deltaic foodplain scenario), affected by unidentified isopters (Serrano-Brañas et al., 2018) and dermestids (Serrano-Bañas et al., 2018; Venegas-Gómez et al., 2024).

Cenozoic evidence of bioerosion in bones in Mexico is scarce, and none of them were produced by insects until now. Bioeroded remains of Cuvieronius sp. produced by bacteria and fungi are known from the Pliocene of Tepeticpac, Tlaxcala, Central Mexico (Straulino et al., 2019). In the Holocene, traces of bioerosion in bones (e.g., dental inlays, cephalic deformations, cranial trepanation) have been reported in from the archaeological records (pre-Hispanic); nevertheless, it has been attributed to cultural (Romero-Molina, 1958; Tiesler, 1994) and/or unintentional factors (cuts, traumatic injury, traces, etc.) caused by fire or even produced by vertebrates activity (Coyoc-Ramirez et al., 2003), rather than insects. Concerning to other localities of Mexico, the presence of insect remains in funerary bundles has been documented in the states of Coahuila (Huchet et al., 2013) and Morelos (Muñiz-Vélez, 2001), however, no traces of bioerosion by insects has been documented in these caves or any other caves in Mexico.

The aim of this work is to report the first evidence of osteophagy by insects in Pleistocene mammal (Cuvieronius hyodon) skeletal remains found in cavernous environment (Loltún Cave) from southeastern Mexico, as well as to provide a discussion concerning the trace-producer and substrate (bone) interaction during the decay process, and the environmental conditions that prevailed in the Loltún Cave during the postmortem exposition.

LOCALITY AND GEOLOGICAL SETTING

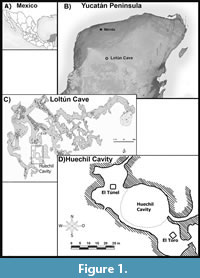

The Loltún Cave is perhaps the most relevant archaeological-paleontological archive in the Yucatán Peninsula, with more than 4000 fossils and subfossils of Nearctic and Neotropical affinities (Schmidt, 1988; Arroyo-Cabrales-Alvares, 2003; Morales-Mejía et al., 2009). This cave is located south-southwest of the municipality of Oxkutzcab, in the southwest of the state of Yucatán, México (Figure 1), within geographic coordinates 20°15'14.35" N and 89°27'20.82" W (Velázquez, 1978; 1980) The site is located on the foothills of the Sierra del Pu’uk (Álvarez and Polaco, 1982), also known as Sierra de Ticul, (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003) where Miocene shallow water carbonates with a content of CaCO3 higher than 89% were affected by acidic groundwaters (Estrada-Medina et al., 2019), that combined with a high precipitation rate in the area and a tropical climate (González-González et al., 2008) displaying different stages of the dissolution process that produced the tunnels and chambers of the complex subterraneous endokarstic systems of which the Loltún Cave is part (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003).

The Loltún Cave is perhaps the most relevant archaeological-paleontological archive in the Yucatán Peninsula, with more than 4000 fossils and subfossils of Nearctic and Neotropical affinities (Schmidt, 1988; Arroyo-Cabrales-Alvares, 2003; Morales-Mejía et al., 2009). This cave is located south-southwest of the municipality of Oxkutzcab, in the southwest of the state of Yucatán, México (Figure 1), within geographic coordinates 20°15'14.35" N and 89°27'20.82" W (Velázquez, 1978; 1980) The site is located on the foothills of the Sierra del Pu’uk (Álvarez and Polaco, 1982), also known as Sierra de Ticul, (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003) where Miocene shallow water carbonates with a content of CaCO3 higher than 89% were affected by acidic groundwaters (Estrada-Medina et al., 2019), that combined with a high precipitation rate in the area and a tropical climate (González-González et al., 2008) displaying different stages of the dissolution process that produced the tunnels and chambers of the complex subterraneous endokarstic systems of which the Loltún Cave is part (Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003).

The Loltún Cave has been studied under different proxies and objectives for several decades. From the late nineteenth century to the mid-twentieth century, several foreign expeditions were made to the cavern (e.g., Mercer, 1896; Hatt et al., 1953). However, paleontological and archeological excavations were carried out at the end of the 1970s by archeologists Norberto González Crespo, Ricardo Velázquez-Valadés, and other members of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH) (Velázquez, 1978, 1980; Álvarez and Polaco, 1982).

The excavations were carried out with a metric grid, with quadrants with units of 1 m2, and areas of 2 m wide × 2 m (or more depending on the need) and controlled stratigraphy during four seasons. The first excavations were carried out in 1977 at the Nahakab entrance, but no remains of pre-ceramic materials were found (Velázquez, 1978). Subsequently, several excavation seasons were carried out (1977-1980) in the Huechil chamber, obtaining the stratigraphic sequence in two units, which correspond to the “El Tunel” Unit and the “El Toro” Unit. In the first unit, seven strata or layers are recognized at a depth of 4.8 m. The second unit exhibits sixteen layers with a depth of 9.5 m (Figure 2). Velázquez (1978) recognized 16 horizons, which were enlisted from the oldest (Layer XVI) to the youngest (Layer I). The levels or layers of the sequence can be divided into three main groups (Schmidt, 1988; Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003) numbered top down but described here in profile-up order:

The excavations were carried out with a metric grid, with quadrants with units of 1 m2, and areas of 2 m wide × 2 m (or more depending on the need) and controlled stratigraphy during four seasons. The first excavations were carried out in 1977 at the Nahakab entrance, but no remains of pre-ceramic materials were found (Velázquez, 1978). Subsequently, several excavation seasons were carried out (1977-1980) in the Huechil chamber, obtaining the stratigraphic sequence in two units, which correspond to the “El Tunel” Unit and the “El Toro” Unit. In the first unit, seven strata or layers are recognized at a depth of 4.8 m. The second unit exhibits sixteen layers with a depth of 9.5 m (Figure 2). Velázquez (1978) recognized 16 horizons, which were enlisted from the oldest (Layer XVI) to the youngest (Layer I). The levels or layers of the sequence can be divided into three main groups (Schmidt, 1988; Arroyo-Cabrales and Álvarez, 2003) numbered top down but described here in profile-up order:

Group 3. Layers IX to XVI are Pleistocene in age, without any cultural material. These layers are formed from reddish clayey sediments except layer XI, composed of volcanic ash correlated to the Rosseau tephra was dated to 28,400 yr by radiocarbon method (uncalibrated, Rampino et al., 1979).

Group 2. Layer VIII is from the Pre-Ceramic Stage; it includes some lithic elements and extinct fauna.

Group 1. Layers I to VII are from the Ceramic Stage (Holocene), but extinct animal remains are found at the bottom of level VII. This group includes layers with clayey sediments of light to dark brown tones.

The remains of Cuvieronius hyodon were found in the last metric level of layer X, at a depth between 3.39 and 3.50 m. This layer is composed of clasts of clayey sediments of light reddish tones, small fragments of carbonate and rocks. Other mammals such as Equus conversidens, Pecari tajacu, Mazama, and Odocoileus virginianus, birds, and reptiles have been found at this same level. The relative age of this layer is calculated ca. 28,400 years, based on the date calculated for the volcanic ash of layer XI (Rampino et al., 1979) as well as 32,782 ±296 yr (Cruz et al., 2016) and confirm the assignation of that level to the Late Pleistocene.

INSTITUTIONAL ABBREVIATIONS

LSAF, Laboratorio de la Sección de Antropología Física, CINAHY, Centro INAH-Yucatán (Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia), MRAMPC, Museo Regional de Anttopología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The bone remains of Cuvieronius hyodon with bioerosion structures from the Loltún Cave analyzed in this study, are deposited in two collections in Mérida, Yucatán: the CINAHY (previously known as the Centro Regional del Sureste), and The Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón (MRAMPC). The CINAHY houses limb remains such as right and left humerus; calcaneum; carpal bones [pyramidal and trapezoid]; and unidentified bones (Figure 3A); cranial elements such as fragments, dental pieces, and the left hemimandible (Figure 3B), all of them registered under the catalog number CINAHY:LOLTUN(P):1978.2.1. The Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón (MRAMPC), curates the largest remains of C. hyodon (Figure 3C) under the following catalogs: upper right incisor (tusk): MM1988.33:1 (10-347041INV); and first right rib: MM1998-33:3(10-347042INV)The bone remains with bioerosion signatures reported in this document were described in the Laboratorio de la Sección de Antropología Física of the Centro INAH-Yucatán, by using optical instruments such as stereoscopic microscope (Trinocular Stereoscopic Microscope AMSZOOM 3.5X - 90X). Morphological aspects, measurements, and classification were reviewed based on the work of Roberts et al. (2007); Pirrone et al. (2014); and Xing et al. (2015). The depth and diameter of the perforations (bioerosions) were measured by using a Lion Tool Q-1500 mm digital caliper (vernier). The recognition of the morphology of the perforations was possible by making silicone molds. Fossil material were photographed by using a digital camera (Canon EOs Revel T7) and included in a database for further analysis in order to recognize the producer organisms and to understand the taphonomic processes involved in the bioerosion structures.

The bone remains of Cuvieronius hyodon with bioerosion structures from the Loltún Cave analyzed in this study, are deposited in two collections in Mérida, Yucatán: the CINAHY (previously known as the Centro Regional del Sureste), and The Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón (MRAMPC). The CINAHY houses limb remains such as right and left humerus; calcaneum; carpal bones [pyramidal and trapezoid]; and unidentified bones (Figure 3A); cranial elements such as fragments, dental pieces, and the left hemimandible (Figure 3B), all of them registered under the catalog number CINAHY:LOLTUN(P):1978.2.1. The Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón (MRAMPC), curates the largest remains of C. hyodon (Figure 3C) under the following catalogs: upper right incisor (tusk): MM1988.33:1 (10-347041INV); and first right rib: MM1998-33:3(10-347042INV)The bone remains with bioerosion signatures reported in this document were described in the Laboratorio de la Sección de Antropología Física of the Centro INAH-Yucatán, by using optical instruments such as stereoscopic microscope (Trinocular Stereoscopic Microscope AMSZOOM 3.5X - 90X). Morphological aspects, measurements, and classification were reviewed based on the work of Roberts et al. (2007); Pirrone et al. (2014); and Xing et al. (2015). The depth and diameter of the perforations (bioerosions) were measured by using a Lion Tool Q-1500 mm digital caliper (vernier). The recognition of the morphology of the perforations was possible by making silicone molds. Fossil material were photographed by using a digital camera (Canon EOs Revel T7) and included in a database for further analysis in order to recognize the producer organisms and to understand the taphonomic processes involved in the bioerosion structures.

The bioerosive structures reported in this study were described as tunnels, notches, and holes, and assigned at the ichnospecies level, following the terminology used by various authors for morphologically similar structures (see Roberts et al., 2007; Britt et al., 2008; Pirrone et al., 2014; Xing et al., 2015; Paes Neto et al., 2016; Parkinson, 2016; Serrano Brañas et al., 2018; Benyoucef and Bouchemla, 2023; Trifiglio et al., 2023; Venegas-Gómez et al., 2024; Alves-Silva et al., 2024).

SYSTEMATIC ICHNOLOGY

Ichnogenus CUBICULUM

Roberts, Raymond and Foreman (2007)

Type ichnospecies. Cubiculum ornatus Roberts, Raymond and Foreman, 2007

Emended Diagnosis (Venegas-Gómez, 2024). “Discrete hollow ellipsoidal to drop-shaped borings considered chambers bored into the surface of inner spongy, outer cortical bone or as subcortical borings with a spongy bone base and a compact bone ceiling. The bases are flat to rounded with smooth to engraved walls perpendicular to the bone surface. The bases can be flat or tapered towards one side. Structures may be isolated but commonly form dense, locally overlapping concentrations. They appear as single-chamber borings or as a composite trace connected with entrance tubes. The chamber is two to six times longer than its diameter”.

See Roberts et al. (2007) for original diagnosis.

Ichnospecies Cubiculum ornatus

Roberts, Raymond, and Foreman (2007)

(Figure 3, Table 1)

Diagnosis. “Discrete ovoid borings in bone. Hollow, elliptical chambers with concave flanks bored into inner spongy and outer cortical bone surfaces. Chamber length three to four times greater than diameter or width. May be isolated, but observed more commonly in dense, sometimes overlapping concentrations. Walls roughened commonly, composed of shallow, arcuate (apparently paired) grooves” (after Roberts et al., 2007).

Description of Bioerosion Structures from the Loltún Cave

A total of 116 bioerosion traces (borings) were recognized in the bones of Cuvieronius hyodon within layer X of the Loltún Cave (Table 1). Ninety-three borings were observed in postcranial bones (six in a complete rib and 87 in 23 small bones or fragments). In the cranial region, 23 traces were found, of which 13 borings in mandible fragments and 10 in teeth (five in a tusk and five in molar fragments). Borings were abundant in fragments and small bones, whereas in large bones and teeth, the number of traces were scarce. They occur in isolated structures or forming overlapping concentrations.

A total of 116 bioerosion traces (borings) were recognized in the bones of Cuvieronius hyodon within layer X of the Loltún Cave (Table 1). Ninety-three borings were observed in postcranial bones (six in a complete rib and 87 in 23 small bones or fragments). In the cranial region, 23 traces were found, of which 13 borings in mandible fragments and 10 in teeth (five in a tusk and five in molar fragments). Borings were abundant in fragments and small bones, whereas in large bones and teeth, the number of traces were scarce. They occur in isolated structures or forming overlapping concentrations.

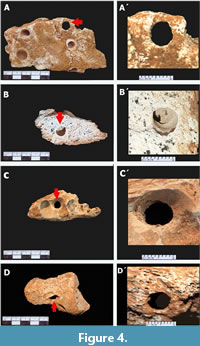

Tunnels. They consist of straight traces with oval entrance that penetrate the bone vertically/parallel to the bone surface. They expose a length that varies from 10 mm to 30 mm with ends having diameters from 8 mm to 11 mm (Figure 4). This type of trace fossils represents the less common bioerosion structure found in Cuvieronius hyodon bone remains from Loltún Cave (N= 7). They were observed in one right humerous, a left calcaneus, and in the limb of three unidentified bones. They are not filled by sediment.

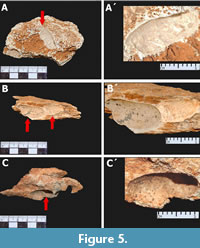

Notches. They represents the most abundant type of trace recorded and is present in all bone and dental remains. They are represented by elongated openings with an ovoid or ellipsoidal outline. According to their depth angle, two types of notches are recognized:

a) Lateral growth notches (Figure 5): They represent the second most abundant of all bioerosion traces (N= 36) and are characterized by having an slightly ellipsoidal and shallow chamber at one end, giving the appearance of lateral growth. However, towards the interior of the structure, the chamber becomes slightly more perpendicular until it reaches the other end, which becomes concave with respect to the wall. This type of chamber has an approximate length-width ratio of 3:1, with a range between 12 mm to 30 mm long, and 9 mm to 11 mm wide. The trace was found in spongy, compact bone or between both, as well as in the dentin of the molar and tusk. It may or may not have filling and the walls have bioglyphs.

Lateral growth notches (Figure 5): They represent the second most abundant of all bioerosion traces (N= 36) and are characterized by having an slightly ellipsoidal and shallow chamber at one end, giving the appearance of lateral growth. However, towards the interior of the structure, the chamber becomes slightly more perpendicular until it reaches the other end, which becomes concave with respect to the wall. This type of chamber has an approximate length-width ratio of 3:1, with a range between 12 mm to 30 mm long, and 9 mm to 11 mm wide. The trace was found in spongy, compact bone or between both, as well as in the dentin of the molar and tusk. It may or may not have filling and the walls have bioglyphs.

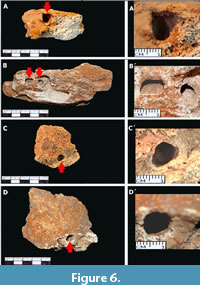

b) Deep notches (Figure 6): They are the most abundant kind of borings (N= 37). They are also showing a quite similar shallow end to the previous one. However, the trace is distinguished from the previous one in that it is inserted perpendicularly or obliquely to the line of bone growth. Its end is also convex. The chamber has a length-width ratio similar to the lateral growth notch, although its depth (length) may be slightly greater. Likewise, they can be found in spongy, compact bone or dentin. It may or may not have filling and the walls have bioglyphs.

Deep notches (Figure 6): They are the most abundant kind of borings (N= 37). They are also showing a quite similar shallow end to the previous one. However, the trace is distinguished from the previous one in that it is inserted perpendicularly or obliquely to the line of bone growth. Its end is also convex. The chamber has a length-width ratio similar to the lateral growth notch, although its depth (length) may be slightly greater. Likewise, they can be found in spongy, compact bone or dentin. It may or may not have filling and the walls have bioglyphs.

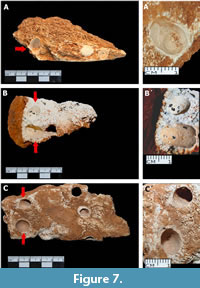

Holes. They are the third most abundant borings in bones (N= 26), but are rare in teeth. They can be found individually, together, or associated with other types of borings. The chamber entrance is a circular or ovoid pit (Figure 7). Its interior is shallow and slightly oblique, and its end is convex. In general, the holes have a diameter-depth ratio of between 1:1 and 1:2. With a diameter range that ranges from 8 mm to 11 mm and a depth that varies from 5 mm to 10 mm. The holes were only observed in spongy bone or dentin. It may or may not have filling and the walls have bioglyphs.

REMARKS

The characteristics of the bioerosive structures described in skeletal remains of Loltún closely resemble those reported in the emended diagnosis of Venegas-Gómez et al. (2014) for the ichnogenus Cubiculum, and mentioned by Roberts et al. (2007), Dominato et al. (2009); Xing et al. (2015); Paes-Neto (2016); Parkinson (2016); Serrano-Brañas et al. (2018), and Venegas-Gómez et al. (2024) for Cubiculum ornatus. This ichnospecies is characterized by ovoid cavities entrances, ellipsoidal chambers present in bones and teeth, with concave wall flanks bored into inner cortical bone surfaces, in spongy bone, and the dentin; the chamber length in most of them is approximately three times longer than the width in the notches. They occur in isolated structures or in concentrations overlapping or in close contact each other, and the presence of well-developed bioglyphs, considered as ichnotaxobases for the ichnogenus. In contrast, Cubiculum inornatus maintains a gross ellipsoidal morphology, has a more pronounced apical constriction, does not exhibit concave walls, and lacks bioglyphs (Xing et al., 2015; Paes-Neto et al., 2016; El Hedeny el al., 2023); C. levis, exhibits a sharply constricted upper margin that detail its particular bowl-shaped morphology and, as well as C. inornatus, bioglyphs are absent (Pirrone et al., 2014, Xing et al., 2015); C. cooperi does not expose concave flats, the trace length is three to four times its diameter, and it also lacks of bioglyphs (Parkinson, 2016); C. atsintli also lacks bioglyphs and exhibits a characteristic drop-like chambers (Serrano-Brañas et al., 2028) and C. subcorticalis has a subcortical natures and exhibits a bone ceiling, features absent in the rest ichnospecies of Cubiculum (Venegas-Gómez, 2024).

The characteristics of the bioerosive structures described in skeletal remains of Loltún closely resemble those reported in the emended diagnosis of Venegas-Gómez et al. (2014) for the ichnogenus Cubiculum, and mentioned by Roberts et al. (2007), Dominato et al. (2009); Xing et al. (2015); Paes-Neto (2016); Parkinson (2016); Serrano-Brañas et al. (2018), and Venegas-Gómez et al. (2024) for Cubiculum ornatus. This ichnospecies is characterized by ovoid cavities entrances, ellipsoidal chambers present in bones and teeth, with concave wall flanks bored into inner cortical bone surfaces, in spongy bone, and the dentin; the chamber length in most of them is approximately three times longer than the width in the notches. They occur in isolated structures or in concentrations overlapping or in close contact each other, and the presence of well-developed bioglyphs, considered as ichnotaxobases for the ichnogenus. In contrast, Cubiculum inornatus maintains a gross ellipsoidal morphology, has a more pronounced apical constriction, does not exhibit concave walls, and lacks bioglyphs (Xing et al., 2015; Paes-Neto et al., 2016; El Hedeny el al., 2023); C. levis, exhibits a sharply constricted upper margin that detail its particular bowl-shaped morphology and, as well as C. inornatus, bioglyphs are absent (Pirrone et al., 2014, Xing et al., 2015); C. cooperi does not expose concave flats, the trace length is three to four times its diameter, and it also lacks of bioglyphs (Parkinson, 2016); C. atsintli also lacks bioglyphs and exhibits a characteristic drop-like chambers (Serrano-Brañas et al., 2028) and C. subcorticalis has a subcortical natures and exhibits a bone ceiling, features absent in the rest ichnospecies of Cubiculum (Venegas-Gómez, 2024).

DISCUSSION

On the Nature of the Bioerosion Traces on the Skeletal Remains of Cuvieronius hyodon

Traces in Cuvieronius hyodon are not comparable in size and morphology to those pits, holes, perforations, or traces produced by the bite action of some known continental predators and/or scavengers from the Pleistocene (e.g., rodents, birds, reptiles) present in the Loltún Cave and the surrounding area (Goff, 1993; Morales-Mejía et al., 2009). Although it is assumed that they also were involved during the decay processes of C. hyodon and the remaining stages of decomposition, consuming soft tissues and/or some bones.

Loltún traces preserved in bone and teeth remains of Cuvieronius hyodon consist of shallow, ellipsoidal borings with oval entrances, disposed in isolated structures or forming isolated or concentrations. They occur in the cortical bone surface as well as the cancellous bone, and within the dentine in teeth. Traces with walls displaying concave flanks; with a length approximately three times bigger than the diameter; and they are characterized by the presence of bioglyphs. Those characters agree with those in Roberts et al. (2007), Dominato et al. (2009), Xing et al. (2015), Paes-Neto (2016), Parkinson (2016), Serrano-Brañas et al. (2018), and Venegas-Gómez et al. (2024) for Cubiculum ornatus, and make the Loltún traces clearly distinguishable of the other five ichnospecies of the ichnogenus Cubiculum (see the section of remarks).

The anatomy and sizes of the bioerosion traces of the Loltún structures suggest that they were created by osteophagous activity in a postmortem stage. For instance, the presence of well-developed bioglyphs on the internal walls of the traces here studied, could be an evidence of the progressive bone perforation made by the mandibula of dermestid larva, as suggested by Laudet and Antoine (2004), Britt et al.(2008), and Parkinson (2022), and documented by Fernández-Jalvo and Marín-Monfort (2008) under laboratory conditions.

In addition, several authors have also suggested that some ichnospecies of the ichnogenus Cubiculum are pupal chambers as a consequence of osteophagus activity of dermestid beetles (Robets et al., 2007; Britt et al., 2008; Parkinson, 2016; Trifilio et al., 2023; Alves-Silva et al., 2024; Venegas-Gómez et al., 2024; Perea et al., 2025). Schwanke and Kellner (1999) described cylindrical borings as supposed dermestid pupation chambers in Triassic vertebrate bones from Brazil, which according to Roberts et al. (2007) could be referable the ichnogenus Cubiculum. These traces could represent the ancient record of this ichnogenus.

Concerning C. ornatus, traces referable to this ichnospecies (see Roberts et al., 2007) and interpreted as dermestid chambers were described from the Neogene of Germany (Tobien, 1965) Plio-Pleistocene of South Africa (Kitching, 1980) and Pleistocene of USA (Martin and West, 1995). Dominato et al. (2009) also associated borings of C. ornatus observed in mastodont cervical vertebrae from the Pleistocene of Brazil to dermestid activity.

The dominance of dermestid beetle marks and the absence of ichnospecies other than C. ornatus in the bones and teeth of Loltún remains unknown, and represents a curious phenomenon that allows discussion about behavioral biology, taphonomy, and preservation vias. Caves often have limited scavenger access, stable microclimates, and slower decay rates conditions ideal for dermestid colonization (Gatta et al., 2021), but less favorable for other osteophagous groups that require open air condition (termites) or specific humidity (darkling beetles). In this context, C. ornatus traces on Pleistocene bone and teeth remains of the gomphotheriid Cuvieronius hyodon likely reflect both the behavioral adaptations of dermestid and the taphonomic filtering on the cave of Loltún, which selectively preserved their osteophagus activity.

According to Cruz et al. (2016), during the Late Pleistocene nearby the Loltún Cave was dominated by an evergreen seasonal forest, tropical deciduous forest, and scrub forest, based on fossil herpetofauna assemblages, contrasting to the current tropical semi-deciduous forest. At that time, the mean annual temperature was of about 25 °C whereas the mean annual precipitation was of around 1,183 mm (Cruz et al., 2016). Those conditions were optimal for the development of large communities of different groups of insects such as Coleoptera (including Dermestidae), Diptera, Blattodea, Lepidoptera, Ephemeroptera, and Himenoptera (Noonan, 1988; Britt et al., 2008), that contain scavenging species. Of these, Diptera and Coleoptera dominated the decomposition process (fresh, swelling, and decay stages according to Goff (1993) within the Loltún Cave by the reasons due the selectivity of the cave. It seems, beetles were responsible for the most disintegration stages in dry soft tissues and bone damages, representing the only bioerosion traces producers.

The modifications of bones vary depending on the producing insect and its life stage; termites and beetles (e.g., families Silphidae, Hysteridae, Tenebrionidae, and Dermestidae) are the only insects bearing the mandibular structure capable of damaging bones; and the dermestids specifically generate destruction of small bones, boring through spongy bones, grooves on the articular surfaces, and depressions in the form of holes (notches, pits, and chambers, as observed in the specimen of C. hyodon in Loltún) for shelter and pupa formation (Roberts et al., 2007; Britt et al., 2008; Pirrone et al., 2014; Xing et al, 2015; Zanetti et al., 2019).

Biostratinomic Processes

The presence of bioerosion traces in the bones of C. hyodon provides important information about its postmortem history, especially concerning taphonomic processes (biostratinomic), as well as paleoecological (biological interactions) and paleoclimatic approaches (Hasiotis, 2004; Holden et al., 2013).

Immediately after the death of the specimen of C. hyodon in Loltún Cave, both internal chemicals and enzymes (autolysis) and microorganisms (putrefaction) stas breaking down its tissues initiating the decomposition process, creating an optimal microenvironment that allowed the colonization of necrophagous invertebrate such as blow flies (Calliphoridae), common flies (Muscidae), and flesh flies (Sarcophagidae), within a few hours to begin laying their eggs on the corpse. Later, other insects such as beetles (e.g., Silphidae, Histeridae) arrive and lay their eggs in natural orifices. Internal gases, a product of both autolysis and putrefaction processes, produced swelling and eventual skin breakdown leading to the active and later to the advanced decay. At that time, infestation by larvae and adult forms of flies, beetles, and their predators (parasitoid wasps, canibism in beetles) occur in the decaying microenvironment, as well as the occurrence of other groups of insects (lepidopters, hymenopters), which are attracted by visceral liquids. Finally, when soft parts start to dry and get harder, dermestid coleoptera arrive to consume dry soft tissues, keratinized parts and bones.

Infestation by beetles, particularly the Dermestidae family, can occur in stages before decomposition (swelling). However, such infestation commonly occurs sometime later, during the dry decomposition stages and the post-decay (Beal, 1991; Richards et al., 1997); as a strategy to avoid competition with other necrophagous insects (Smith, 1986; Britt, 2008; Byrd and Castner, 2009). Male and female dermestids mate and feed on moist or dry muscle tissue, as well as remnants of ligamentous tissue left behind by other carrion insects (Braack, 1987). They also have a jaw strong enough to chew hard parts such as bones (Schroeder et al., 2002). Dermestid infestation not only depends on the state of decomposition of the corpse, but climatic conditions are also undoubtedly an important factor, for example, the temperature of the environment must be above 20 °C (Wilches et al., 2016); The optimum being between 25 - 35 °C, with a preferably dry environment (Richardson and Goff, 2001; von Hoermann et al., 2011; Parkinson, 2016), which is consistent to paleoclimatic data provided by Cruz et al. (2016).

During oviposition and hatching of the dermestids, the larvae feed on the remains of soft tissues, especially on dry skin left by the adults, who have already left the site at this point (Parkinson, 2016). The consumption of the soft parts and carcasses by the deremestids could take weeks or even months, as occurs in the remains of large mammals (Sullivan and Romney, 1999). According to the body dimensions of the specimen of C. hyodon of Loltún, the complete decay process could take over one year or even more. After nutrient depletion, the larvae reach their final period of development, which under normal conditions pupation would occur within the larval mold or away from the decomposing body, as a strategy to avoid predation or cannibalism (Kreyenberg, 1928).

So far, the reason why only dermestid borings are exposed in the Cuveronius bones remains unknown, since extant species commonly feed on soft or dry tissues. Backwell et al. (2012) propose that these bone modifications occur as an indicator of environmental stress, since when the colony of dermestids has little food and nesting substrates they cause greater damage to the bones. On the other hand, Parkinson (2022), considers the smaller the amount of food, the less damage the insects produce, which means that under stress conditions, the insects do not have enough energy to mark the bone remains. In the case of Loltún Cave, during the stages of decomposition of the body of C. hyodon, the dermestid colony could only have thrived under warm climatic conditions, with a prolonged period of drought, indicated by the tolerance ranges of the dermestids themselves (Richardson and Goff, 2001). The large body dimensions of the C. hyodon allowed it to nourish the colony for a long time (one or more years), as extrapolated in the gomphoter from Aráxa, Brazil (Dominato et al., 2009). After this time, the colony would enter its stress phase, since the bone remains would remain the only source of food and substrate available for pupation.

After the decomposition process, the bones of C. hyodon were exposed to the elements inside the Huechil chamber. The whitening of the bone remains indicates that they were exposed for a long period to the sun’s UV rays that enter directly through the hole. This suggests that the C. hyodon of Loltun died in the cavity area of the Huechil chamber, and not within the “El Toro” rock shelter where the material was found. Furthermore, access from other galleries of the cavern to the Huechil chamber is very narrow, which makes it impossible for large animals to pass from the interior, with the cavity being the only access route (Chan-Mau, 2018). The Huechil chamber is a sinkhole that presents different light, temperature, and humidity conditions than other chambers in the cave, allowing the establishment of plant communities and access for some animals, which in some cases functioned as a natural trap (Xelhuantzi, 1986). It is likely that, in the rainy seasons, water currents formed capable of dragging the skeletal remains of C. hyodon into the “El Toro” rock shelter. The movement caused by the water would cause abrasion in the bones, which over time would be expressed as a superficial rounding in most bone remains. The manganese stains on some bones would indicate that they were underwater for a long time before being buried.

The Temporal Distribution of Cubiculum and Their Known Ichnospecies.

The geologic record of the six ichnospecies of the ichnogenus Cubiculum is well known. So far, C. ornatus was first described in the late Cretaceous of Madagscar by Roberts et al. (2007). Subsecquent discoveries are known from the Upper Cretaceous of Morocco (Ibrahim et al., 2014) and the Pleistocene of Brazil (Dominato et al., 2009). Nevertheless, according to Roberts et al. (2007) traces that display morphological similarities to those observed in C. ornatus are known from Jurassic to Pleistocene deposits of North America, Asia, Europe, and Africa, and represents the ichnospecies with the larger stratigraphic rank and the widest world distribution, showing a remarkable ichnotaxonomic stability as well as a biogeographic continuity through time.

C. inornatus has been described from the Middle Triassic (Paes-Neto et al., 2016) and Pleistocene (Alves-Silva et al., 2024) and the Middle Jurassic of China (Xing et al., 2015). The bowl-shaped C. levis, is known only from the Cretaceous of Argentina (Pirrone et al., 2014), C. cooperi is known from the Upper Cretaceous of Mexico (Serrano-Brañas et al., 2018) and the Pleistocene of South Africa (Parkinson, 2016), whereas the Mexican ichnospecies C. atsintli and C. subcorticalis have been reported only from the Upper Cretaceous of Northeastern Mexico.

The finding of C. ornatus in the Pleistocene of Yucatán extends the known range of the ichnogenus into tropical karstic regions of North America, particularly in the northern lowland tropics of the Neotropical realm. During the Pleistocene, climatic variations played an important role in the distribution of dermestids. In the Nearctic realm, they were restricted to areas around 40 °N latitude during interglacial episodes, but during glacial episodes, their distribution was more limited to seasonality (Martin and West, 1995; Holden et al., 2013). Neotropical species, on the other hand, may have been larger and more active in tropical environments between latitudes 20 °N and 20 °S, based on records from Yucatán, Mexico (this work), and Minas Gerais, Brazil (Dominato et al., 2009; 2011).

CONCLUSION

The boring in C. hyodon bones, and teeth of Loltún Cave, are one of the few records of osteophagy by insects in fossil bones documented for continental environments in Mexico. However, it is the first to be documented in a continental cavernous environment during the Pleistocene in Mexico. There are probably other continental Pleistocene records with insect perforations in Mexico, rather than human or other factors as suggested by Romero-Molina, (1958) and Tiesler (1995), among others.

The importance of the bioerosion traces in bones of the study material is not only in the identification of the ichnospecies Cubiculum ornatus and its producer as an osteophagous beetle of the Dermestidae family. Its discovery allows us to recapitulate the post-mortem history of C. hyodon, providing valuable taphonomic (biostratonomic), paleoecological (interspecific interactions), and paleoclimatic (temperature and humidity) information. The finding of C. ornatus in the Pleistocene of Yucatán represent the first record of the ichnogenus and the ichnospecies in to tropical North America.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Centro INAH-Yucatán and the Museo Regional de Antropología de Yucatán, Palacio Cantón for allowing us to review and analyze the paleontological material from Cueva Loltún. The Consejo Nacional de Humanidades, Ciencia y Tecnología for providing the postdoctoral fellowship for the first author (CONAHCYT 668191). Special acknowledgment goes to the Streasser-Peán Foundation for financing the laboratory equipment.

REFERENCES

Álvarez, T. and Polaco, O.J. 1982. Restos de moluscos y mamíferos cuaternarios procedentes de las grutas de Loltún, Yucatán, México: Cuadernos de Trabajo 26, Departamento de Prehistoria, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Ciudad de México.

Alves-Silva, L., Araujo, R., de Souza Barbosa, F.H., and de Araújo-Júnior, H.I. 2024. Necrophagous insect damage on Quaternary mammal bones from Brazilian caves: Taphonomic and paleoecological implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 150: 105236.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2024.105236

Arroyo-Cabrales, J. and Álvares, T. 1990. Restos oseos de murciélagos procedentes de las excavaciones de las grutas Loltún. Colección Científica (Serie Prehistoria), Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, 194:1-103.

Arroyo-Cabrales, J. and Álvarez, T. 2003. A preliminary report of the late Quaternary mammal fauna from Loltún Cave, Yucatán, México, p. 262-272. In Schubert, B.W., Mead, J.I., and Graham, R.W. (eds.), Ice age cave faunas of North America. Indiana University Press, Indiana.

Augustin, F.J., Matzke, A.T., Maisch, M.W., and Pfretzschner, H. 2021. Dinosaur taphonomy of the jurassic shishugou formation (northern junggar basin, NW China) - insights from bioerosional trace fossils on bone. Ichnos, 28:87-96.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2021.1890590

Backwell, L., Parkinson, A., Roberts, E., D’Errico, F., and Huchet, J.B. 2012. Criteria for identifying bone modification by termites in the fossil record. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimate, Palaeoecology, 337-338:72-87.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2012.03.032

Bader, K.S., Hasiotis, S.T., and Martin, L.D. 2009. Application of forensic science techniques to trace fossils on dinosaur bones from a quarry in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Northeastern Wyoming. Palaios, 24:140-158.

https://doi.org/10.2110/palo.2008.p08-058r

Beal, R. 1991. Dermestidae (Bostrichoidea) (including Thorictidae, Thylodriidae), p. 434-439. In Stehr, F. (ed.), Immature insects. Kendall Hunt Publishing. Westmark Drive, Dubuque.

Bertling, M., Braddy, R., Bromley, R.G., Demathieu, G., Genise, J., Mikula R., Nielsen, J., Nielsen, K., Rindsberg, A., Schlirf, M., and Uchman, A. 2006. Names for trace fossils: A uniform approach. Lethaia, 39:265-286.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00241160600787890

Benyoucef, M. and Bouchemla, I. 2023. First study of continental bioerosion traces on vertebrate remains from the Cretaceous of Algeria. Cretaceous Research, 152: 105678.

https:// doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105678

Braack, L.E.O. 1987. Community dynamics of carrion-attendant arthropods in tropical African woodland. Oecologia, 72(3):402-409.

https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00377571

Britt, B.B., Scheetz, R.D., and Dangerfield, A. 2008. A suite of dermestid beetle traces on Dinosaur bone from the upper Jurassic Morrison Formation, Wyoming, USA. Ichnos. 15(2):59-71.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940701193284

Byrd, J.H. and Castner, J.L. 2009. Forensic Entomology. The Utility of Arthropods in Legal Investigations. CRC Press LLC, Boca Raton, Florida.

Campobasso, C., Vella, G., and Introna, F. 2001. Factors affecting decomposition and diptera colonization. Forensic Science International, 120:18-27.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(01)00411-X

Chan-Mau, P.T. 2018. Estudio de avifauna del Cuaternario tardío procedente de las Grutas Loltún, Yucatán, México. Unpublished Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Ciudad de México, México.

Chin, K. and Bishop, J.R. 2006. Exploited twice: bored bone in a theropod coprolite from the Jurassic Morrison Formation of Utah, USA, p. 379-387. In Bromley, R.G., Buatois, L.A., Mángano, G., Genise, J.F., and Melchor, R.N. (eds.), Sediment-organism Interactions: A Multifaceted Ichnology. SEPM Special Publication 88.

https://doi.org/10.2110/pec.07.88.0379

Cruz, J.A., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., and Reynoso, V.H. 2016. Reconstructing the paleoenvironment of Loltún Cave, Yucatán, Mexico, with Pleistocene amphibians and reptiles and their paleobiogeographic implications. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 33(3):342-354.

https://doi.org/10.22201/cgeo.20072902e.2016.3.441

Coyoc-Ramirez, M., Maldonado-Cardenas, R., and Ortega-Muñoz, A. 2003. Los huesos humanos perforados de Dzibilchaltun, Yucatán, México. Memorias. XI Encuentro Internacional: Los Investigadores de la Cultura Maya 2009. Tomo II. Universidad Autónoma de Campeche, San Francisco de Campeche, Campeche.

Cruickshank, A.R.I. 1986. Archosaur predation on an east African Middle Triassic dicynodont. Palaeontology, 29:415-422.

https://www.palass.org/sites/default/files/media/publications/palaeontology/volume_29/vol29_part2_pp415-422.pdf

Cunha, L.S., Dentzien-Dias, P., and Francischini, H. 2024. New bioerosion traces in rhynchosaur bones from the Upper Triassic of Brazil and the oldest occurrence of the ichnogenera Osteocallis and Amphifaoichnus. Acta Palaeontologuca Polonica, 69 (1), 1-21.

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.01093.2023

Currie, P.J. and Jacobsen, A.R. 1995. An azhdarchid pterosaur eaten by a velociraptorine theropod. Canadian Journal of Earth Science, 32:922-925.

https://doi.org/10.1139/e95-077

Dominato, V.H., Mothé, D., Santos-Avilla, L., and Bertoni-Machado, C. 2009. Ação de insetos em vértebras de Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia, Gomphotheriidae) do Pleistoceno de Águas de Araxá, Minas Gerais, Brasil. Revista Brasileira de Paleontologia, 12(1):77-82,

https://doi.org/10.4072/rbp.2009.1.0

Dominato, V.H., Santos-Avilla, L., Costa da Silva, R., and Pomar, D. 2010. Registro da ação de besouros necrófagos (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) em restos de Stegomastodon waringi (Gomphotheriidae: Mammalia) do Pleistoceno da Colômbia. 7º Simposio Brasileiro de Paleontologia de vertebrados, Rio de Janeiro, p.18-23

El Hedeny, M., Mohesn, S., Tantawy, A., El-Sabbagh, A., AbdelGawad, M., El Kheir, G. A. 2023. Bioerosion traces on Campanian turtle remains: New data from the laggonal deposits of the Quseir Formation, Kharga Oasis, Egypt. Palaeontologia Electronica, 26(3):a40.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1315

Estrada-Medina, H., Jiménez-Osornio, J.J., Álvarez-Rivera, O., and Barrientos-Medina, R.C. 2019. El karst de Yucatán: su origen, morfología y biología. Acta Universitaria 29, e2292.

https://doi.org/10.15174.au.2019.2292

Fernández-Jalvo, Y. and Marín-Monfort, M.D. 2008. Experimental taphonomy in museums: Preparation protocols for skeletons and fossil vertebrates under the scanning electron microscopy. Geobios, 41:157-181.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2006.06.006

Gatta, M., Rolfo, M.F., Salari, M., Jacob, E., Valentini, F., Scevola, G., Doddi, M., Neri, A., and Martín-Vega, D. 2021. Dermestid pupal chambers on Late Pleistocene faunal bones from Cava Muracci (Cisterna di Latina, central Italy): Environmental implications for the central Mediterranean basin during MIS 3. Jornal of Archaeological Science. Reports 35, 102780.

Gianechini, F.A. and De Valais, S. 2015. Bioerosion trace fossils on bones of the Cretaceous South American theropod Buitreraptor gonzalezorum Makovicky, Apesteguía and Agnolín, 2005 (Deinonychosauria). Historical Biology: An International Journal of Paleobiology, 28(4):1-17.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2014.991726

Goff, M.L. 1993. Estimation of postmortem interval using arthropod development and successional patterns. Forensic Science Review, 5(2):81-9.

https://doi.org/10.1097/00000433-198809000-00009

González-González, A., Rojas, C., Terrazas, A., Benavente M., Stinnesbeck, W., Avilés J., de los Ríos, M., and Aceves, E. 2008. The arrival of Humans on the Yucatán Peninsula: Evidence from Submerged Caves in the State of Quintana Roo México, Current Research in the Pleistocene, 25:1-9

Hasiotis, S.T. 2004. Reconnaissance of Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation ichnofossils, Rocky Mountain Region, USA: paleoenvironmental, stratigraphic, and paleoclimatic significance of terrestrial and freshwater ichnocoenoses. Sedimentary Geology. 167(3):177-268

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.006

Hasiotis, S.T., Fiorillo, A.R., and Hanna, R.1999. Preliminary report on borings in Jurassic dinosaur bones: Evidence for invertebrate-vertebrate interactions, p. 193-200. In Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah: Utah Geological Survey; Miscellaneous Publication 99-1, Salt Lake City, Utah.

Hatt, R.T., Fisher, I., Lanfebartel, D.A., and Brainerd, G.W. 1953. Faunal and Archaeological Researches in Yucatán Caves. Cranbrook Institute of Science Bulletin 33:1-119.

Holden, A.R., Harris, J.M., and Timm, R.M. 2013. Paleoecological and Taphonomic Implications of Insect-Damaged Pleistocene Vertebrate Remains from Rancho La Brea, Southern California. PLoS ONE 8(7):e67119.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0067119

Huchet, J.B., Pereira, G., Gomy, Y., Phillips, T.K., Alatorre-Bracamontes, C.E., Vásquez-Bolaños, M., and Mansilla, J. 2013. Archaeoentomological study of a pre-Columbian funerary bundle (mortuary cave of Candelaria, Coahuila, Mexico). Annales de la Société entomologique de France (N.S.), 49(3):277-290.

https://doi.org/10.1080/00379271.2013.845474

Ibrahim, N., Varricchio, D.J., Sereno, P.C., Wilson, J.A., Dutheil, D.B., Martill, D.M., Baidder, L., and Zouhriet, S. 2014. Dinosaur Footprints and Other Ichnofauna from the Cretaceous Kem Kem Beds of Morocco. PLoS ONE 9(3):e90751.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0090751

Kitching, J. W. 1980. On some fossil arthropoda from the Limeworks, Makapansgat, Potgietersrus. Palaeontologia Africana, 23:63-68.

Kreyenberg, J. 1928. Experimentell-biologische Untersuchungen uber Dermestes lardarius L. und Dermestes vulpinus F. Ein Beitrag zur Frage nach der Inkonstanz der Haut-ungszahlen bei Coleopteren Zeitschrift fuer Angewandte Entomologie 14:140-188.

Laudet, F. and Antoine, P.O. 2004. Des chambres de pupation de Dermestidae (Insecta: Coleoptera) sur un os de mammif`ere Tertiaire (phosphorites du Quercy): implications taphonomiques et pal´eoenvironnementales. Geobios, 37(3):376-381.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geobios.2003.04.005

Martin, L.D. and West, D.L, 1995. The recognition and use of dermestid (Insecta, Coleoptera) pupation chambers in paleoecology. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 113:303-310.

https://doi.org/10.1016/0031-0182(95)00058-T

McHugh, J.B., Drumheller, S.K., Riedel, A., and Kane, M. 2020. Decomposition of dinosaurian remains inferred by invertebrate traces on vertebrate bone reveal new insights into Late Jurassic ecology, decay, and climate in western Colorado. PeerJ 8:e9510

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.9510

Mercer, H.C. 1896. The Hill-caves of Yucatan: A Search for Evidence of Man’s Antiquity in the Caverns of Central America. Monographs. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, Oklahoma

Morales-Mejía, F.M., Arroyo-Cabrales, J., and Polaco, O. 2009. New Records for the Pleistocene Mammal Fauna from Loltún Cave, Yucatán, México. Paleoenvironments: Vertebrates and Invertebrates, 26:166-168.

Muniz-Velez, R. 2001. Restos de insectos antiguos recuperados en la cueva “La Chagüera” del Estado de Morelos, México. Acta Zoológica Mexicana, 83:115-125.

https://doi.org/10.21829/azm.2001.83831857

Neumann, A.C. 1966. Observations on coastal erosion in Bermuda and measurements of the boring rate of the sponge, cliona lampa. Limnology and Oceanography, 11(1): 92-108.

https://doi.org/10.4319/lo.1966.11.1.0092

Nolte, M.J., Greenhalgh, B.W., Dangerfield, A., Schee, R.D., and Britt, B.B. 2004. Invertebrate burrows on dinosaur bones from the Lower Cretaceous Cedar Mountain Formation near Moab, Utah, USA. Proceedings of the Geological Society of America, Abstracts with Programs, Denver, Colorado, 36(5):379A.

Noonan, G.R, 1988. Biogeography of North American and Mexican Insects, and a Critique of Vicariance Biogeography, 37(4):366-384

https://doi.org/10.2307/2992199

Odes, E.J., Parkinson, A.H., Randolph-Quinney, P.S., Zipfel, B., Jakata, K., Bonney, H., and Berger, L.R. 2017. Osteopathology and insect traces in the Australopithecus africanus skeleton StW 431. South African Journal of Science, 113:1-7.

https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2017/20160143

Paes-Neto, V.D., Parkinson, A.H., Pretto, F.A., Soares, M.D., Schwanke, C. Schultz, C.L., and Kellner, A.W. 2016. Oldest evidence of osteophagic behaviour by insects from Triassic of Brazil. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology, 453: 3041.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2016.03.0260031-0182

Paik, I.S. 2000. Bone chip-filled burrows associated with bored dinosaur bone in floodplain paleosols of the Cretaceous Hasandong Formation, Korea. Palaeogeograpy, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology, 157(3-4):213-225.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0031-0182(99)00166-2

Parkinson, A.H. 2016. Traces of insect activity at Cooper's D fossil site (Cradle of Humankind, South Africa). Ichnos, 23:322-339.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2016.1202685

Parkinson, A.H. 2022. Modern bone modification by Dermestes maculatus and criteria for the recognition of dermestid traces in the fossil record. Historical Biology, 35(4): 567-579.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2022.2054714

Perea, D., Verde, M., Montenegro, F., Toriño, P., Manzuetti, A., and Roland, G. 2020. Rastros de insectos fósiles en gliptodontes de Uruguay, Ichnos, 27(1):70-79,

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2019.1584562

Perea, D., Verde, M., Mesa, V., Soto, M., Montenegro, F. 2025. Bioerosion Structures on Dinosaur Bones Probably Made by Multituberculate Mammals and Dermestid Beetles (Guichón Formation, Late Cretaceous of Uruguay). Fossil Studies, 3(2):1-10.

https://doi.org/10.3390/fossils3010002

Pirrone C.A., Buatois, L.A., and Bromley, R.G. 2014 Ichnotaxobases for Bioerosion Trace Fossils in Bones. Journal of Paleontology, 88(1):195-203.

https://doi.org/10.1666/11-058

Rampino, M.R., Self, S., and Fairbridge, R.W. 1979. Can rapid climate change cause volcanic eruptions?. Science, 206:826-829.

https://doi.org/10.1126/ciencia.186.4158.49

Richards, E.N. and Goff, M.L. 1997. Arthropod succession on exposed carrion in three contrsting tropical habitats on Hawaii Island, Hawaii. Journal of Medical Entomology, 34:328-339.

https://doi.org/10.1093/jmedent/34.3.328

Richardson, M.S. and Goff, M.L. 2001. Effects of Temperature and Intraspecific Interaction on the Development of Dermestes maculatus (Coleoptera: Dermestidae). Journal of Medical Entomology, 38:347-351.

https://doi.org/10.1603/0022-2585-38.3.347

Roberts, E.M., Raymond, R.R., and Foreman, B.Z. 2007. Continental insect borings in dinosaur bone: examples from the Late Cretaceous of Madagascar and Utah. Journal of Paleontology, 81(1):201-208.

https://doi.org/10.1666/00223360(2007)81[201:CIBIDB]2.0.CO;2

Rogers, R.R. 1992. Non-marine borings in dinosaur bones from the Upper Cretaceous Two Medicine Formation, northwestern Montana. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 12(4):528-531.

https://doi.org/10.1080/02724634.1992.10011479

Romero-Molina, J. 1958. Mutilaciones dentarias prehispánicas de México y América en general. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. México, D.F.

Saneyoshi, M., Watabe, M., Suzuki, S., and Tsogtbaatar, K. 2011. Trace fossils on dinosaur bones from Upper Cretaceous eolian deposits in Mongolia: taphonomic interpretation of paleoecosystems in ancient desert environments. Palaeogeograpy, Palaeoclimatology, and Palaeoecology, 311(1-2):38-47.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.palaeo.2011.07.024

Serrano-Bañas, C.I., Espinosa-Chávez, B., and Maccracken, A.S. 2018. Insect damage in dinosaur bones from the Cerro del Pueblo Formation (Late Cretaceous, Campanian) Coahuila, Mexico. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 86:353-365.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2018.07.002

Schmidt, P.J. 1988. La entrada del hombre en la Península de Yucatán, p. 25-261. In González-Jácome, A. (ed.), Orígenes del hombre americano. Secretaría de Educación Pública., D.F. México.

Schroeder, H., Klotzbach, H., Oesterhelweg, L., and Püschel, K. 2002. Larder beetles (Coleoptera, Dermestidae) as an accelerating factor for decomposition of a human corpse. Forensic Science International, 127:231-236.

https://doi.org/10.1016/S0379-0738(02)00131-7

Schwanke, C. and Kellner, A. 1999. Presence of insect? Borings in synapsid bones from the terrestrial Triassic Santa Maria Formation, southern Brazil. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology, 19(Suppl. 3), 74A.

Smith, K.G.V. 1986. A Manual of Forensic Entomology. Trustees of the British Museum (Natural History) and Cornell University Press, Cromwell Road, London.

Straulino, L., Mainou, L., Pi, T., Sedov, S., López-Corral, A., Santacruz-Cano, R., and Vicencio-Castellanos, A.G. 2019. Approach to the knowledge of preservation of pleistocenic bone: The case of a Gomphothere cranium from the site of Tepeticpac, Tlaxcala, Mexico. Revista Mexicana de Ciencias Geológicas, 36(2):170-194.

https://doi.org/10.22201/cgeo.20072902e.2019.2.1036

Sullivan L.M. and Romney, C.P. 1999. Cleaning and Preserving Animal Skulls. College of Agriculture and Life Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona.

Tiesler, V. 1994. La deformación cefálica intencional entre los mayas prehispánicos: aspectos morfológicos y culturales. Colección Científica, D.F. México.

Tobien, H. 1965. Insecten-Frasspuren an tertian und pleistozanen Saugertier-Knochen. 762 Senckenbergiana lethaea, 46:441-451.

Trifilio, L.H.M.D.S., Junior, H.I.D.A., and Porpino, K.D.O. 2023. The paleoichnofauna in bones of Brazilian Quaternary cave deposits and the proposition of two new ichnotaxa. Ichnos: 30 (3), p.207-234.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10420940.2023.2271125

Velázquez, R. 1978. Informe de los trabajos de campo, realizados en las excavaciones de la Gruta Loltún, Yucatán: Durante el periodo de Junio a Diciembre de 1978. Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, Mérida, Yucatán.

Velázquez, R. 1980. Recent discoveries in the caves of Loltún, Yucatan, Mexico. Mexicon, 2(4):53-55.

Venegas-Gómez, C., Ortega-Flores, B., Estrada-Ruiz, E., Pérez-Crespo, V.A., and Aguilar-Arellano, F.J. 2024. Ichnological records associated with dermestid beetles in dinosaur bones from Lala’s Place (Maastrichtian), Ramos Arizpe, Coahuila, Mexico, and their taphonomic implications. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 147:1-17.

https//doi.org.10.1016/j.jsames.2024.1/105110

von Hoermann, C., Ruther, J., Reibe, S., Madea, B., and Ayasse, M. 2011. The importance of carcass volatiles as attractants for the hide beetle Dermestes maculatus (De Geer). Forensic Science International. 212(1-3):173-179.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.forsciint.2011.06.009

West, D.L. and Martin, L.D. 2002. Insect trace fossils as environmental/taphonomic indicators in archaeology and paleoecology, p. 163-173. In Dort, W.J. (ed.), TERTIARY-QUATERNARY Symposium Series 3, Insititute for Tertiary-Quaternary Studies. University of Kansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

West, D.L. and Hasiotis, S.T. 2007. Trace fossils in an archeological context: Examples from bison skeletons, Texas, USA, p. 545-561. In Miller, III W. (ed.), Trace Fossils: Concepts, Problems, Prospects. Elsevier, Amsterdam.

https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044452949-7/50160-1

Wilches, D.M., Laird, R.A., Floate, K.D., and Fields, P.G. 2016. A review of diapause and rtolerance to extreme temperatures in dermestids (Coleoptera). Journal of Stored Products Research, 68:50-62.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jspr.2016.04.004

Xelhuantzi, M.S. 1986. Estudio Palinológico del perfil estratigráfico de la Unidad “El Toro”, Grutas de Loltún, Yucatán. Cuadernos de trabajo, Departamento de Prehistoria, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. 31:1-49.

https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/kip_articles/7181

Xing, L., Parkinson, A.H., Rand, H., Pirronee, C.A., Roberts, E.M., Zhanga, J., Burnsg, M.E., Wangh, T., and Choiniere, J. 2015. The earliest fossil evidence of bone boring by terrestrial invertebrates, examples from China and South Africa. Historical Biology, 28(8):1108-1117.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2015.1111884

Zanetti, N., Ferrero, A., and Centeno, N. 2019. Depressions of Dermestes maculatus (Coleoptera: Dermestidae) on bones could be pupation chambers. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology, 40:122-124.

https://doi.org/10.1097/PAF.0000000000000449

Zonneveld, J.P., Wilson, O., and Holroyd, P. 2024. Composite ichnological-pathological evidence for arthropod parasitism on osteoderms of Boreostemma acostae (Glyptodontidae, Cingulata) from La Venta, Colombia. Journal of South American Earth Sciences, 146:105085.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2024.105085