Volume 28.2

May–August 2025

Full table of contents

ISSN: 1094-8074, web version;

1935-3952, print version

Recent Research Articles

See all articles in 28.2 May-August 2025

See all articles in 28.1 January-April 2025

See all articles in 27.3 September-December 2024

See all articles in 27.2 May-August 2024

Interested in submitting a paper to Palaeontologia Electronica?

Click here to register and submit.

Article Search

Phil Senter

Phil Senter

Department of Biological Sciences

Fayetteville State University

1200 Murchison Road

Fayetteville, North Carolina 28301

U.S.A.

psenter@uncfsu.edu

Phil Senter is a herpetologist and vertebrate paleontologist who teaches zoology and anatomy courses at Fayetteville State University (Fayetteville, North Carolina). He has published over 50 articles on dinosaur paleobiology, the natural history of African snakes, and the creation-evolution debate.

Darius M. Klein

Darius M. Klein

Department of Comparative Literature

Ballantine Hall 914

Indiana University

Bloomington, Indiana 47405

U.S.A.

damaklei@umail.iu.edu

Darius Klein is an antiquarian and translator. He has translated numerous Renaissance European works from Latin into English. He is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Comparative Literature at Indiana University.

APPENDIX

English translation of Giovanni Faber’s latin description of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon. The following translation is by D.K. Notes in square brackets are by D.K. and are not in the original document.

The Miniature One-Horned Dragon

of the Most Illustrious Cardinal Barberini

If one extends this animal lengthwise and measures it from head to tail, its length is one span and four fingers crosswise [A span is the width of a human hand, measured from the tip of the thumb to the tip of digit V (approximately eight and seven/twenty-fourths of an inch, or 211 millimeters by the ancient Roman standard, but with later regional variations). By “crosswise”, what is meant is across the fingers in a horizontal direction as they are held together. The “exact” measurements associated with these terms varied from country to country, region to region; the Roman measurements are cited here.]. The head is oblong and beaked, and its tip is composed entirely of horn. The mouth of the specimen is larger than one would expect for an animal of this size. Three molars apiece can be found in each jaw, along with certain projections and serrations of a horny material which prominently protrude; there are twelve molars altogether. There is also a pair of canine teeth in each jaw, fearsome in appearance but not protruding; the upper ones are a little larger than the lower. Along with these teeth, six other incisors can be seen, with the upper ones being larger than the lower by far. The upper incisors are themselves of unequal length: the two incisors next to the canines are a little more elongated than the four middle ones, which are plainly all of the same size. Those six incisors which can be found in the lower jaw are so small that it is necessary to view them with a magnifying lens, if one wishes to discern them. For this reason, I employed my microscope and was thus able to detect twenty-eight teeth all in all.

It is possible to see the eye-sockets, now empty and quite large, as well as ears which still bear skin, but are sunken and deep, nor small in size. At the crown of the head a small horn protrudes, which one would marvel to see. It is jointed at the tip like an index finger, long, and having a curvature which extends in the opposite direction of the curvature of the neck. It is protected by a scaly skin, an integument made attractive by its little, variegated nodules, which, when slightly torn, exhibit a horny substance underneath themselves which shines very prettily. The entire head is the length of two fingers crosswise, and has the thickness of a thumb. The neck, when extended from the head, is the length of the Lesser Palm, or four fingers [approximately three inches/seventy-four millimeters in length, in Rome], until it reaches the first vertebrae of the thorax. The neck is the thickness of an index finger where it adjoins the upper end of the thorax; it extends horizontally over the breast, which is the thickness of a thumb. The site and position of the neck is the same as what is fou

But by beginning from the end of the tail, I was able to enumerate thirty vertebrae all the way to the mouth of the sacrum, which finishes at the final rib of the belly. These vertebrae are indeed very polished and thoroughly denuded of flesh, and being very tightly and firmly connected they adhere to one another as if held by some sort of extremely tenacious glue, or silver thread that appeared as if it had come into being in the skeleton, causing the vertebrae to become compact and elegantly twisted, moreover, into a spiral.

The jointed bones of the femur, which are the length of two fingers crosswise, adhere to the clavicles, while the tibiae are slightly smaller. Very small feet are joined to the tibiae, divided into four digits armed with rather sharp talons, of almost equal length, and not connected, as far as I could tell, by any membrane. Next to the four digits is the fifth, which is like a thumb in appearance--that is, shorter than the other digits, and located in the internal part of the foot.

This specimen bears two more or less quadrangular wings the width of two fingers, and a little longer than three fingers; the quadrangular shape is mitigated by the fact that the edges of the wings end in three sharply curved points, between which are two indentations of a half-moon shape. At the apex of each wing, directly above the place where the wings arise from the body, two small claws are visibly displayed. The lower border of the wings is close to the belly [It is difficult to see how this is so from the illustration, unless “belly” means “abdomen”], and is shorter in length than the upper border. The wings are joined to the body between the seventh and eighth ribs - that is, right in the middle of the fourteen ribs. When the wings are extended, they do not raise the borders of their most extreme points up high, but extend it toward the tail--in the manner of true birds, as I (and anyone else) would diligently note here. It appears, moreover, that the wings are not composed of feathers, but rather consist of a certain thin skin, with three nerves [note by P.S.: this is a term for internal struts such as those in the wing of an insect or the fingers in the wings of a bat] in each wing; these nerves, composed of rather tough fibers, run along the length of the wings and strengthen the skin. No other small claws, besides the insignificant and scarcely conspicuous ones mentioned above, are visible along the edges of the wings. The wings are accordingly more or less identical to those of bats, which use their wings to cling to walls, ramparts, and trees.

This cutaneous membrane of the wings, moreover, is transparent by candlelight. Their color on the internal side is a dark, wheaten hue, while that of the external part is blue, with a slightly red and black tint when reflecting light. These are distinct from a number of small orbs, both oblong and ovoid in shape, and similar in appearance to peacocks’ eyes [i.e., the “eyes” on a peacock’s tail], which in us instilled more of a sense of delight than terror.

The bones of the jaws, femurs, thorax, and vertebrae of the tail, as well as the many ribs, are entirely bereft of flesh; accordingly, they can be described as similar not to the spines of fish and snakes, but to those of birds and mammals. The skin or hide, by which the entire animal is covered [The specimen is apparently mummified, in that there is no flesh, while the skin remains], seems reptilian [ serpentina ] rather than that of any other animal. Its color is varied, a mixture of an aquamarine tone, a yellowish hue, and a blackish hue. On the back and upper part of the creature’s body it is more of a green color, while the underside, including the neck and belly, is more yellow.

And this concludes a concise description, and indeed genuine and most accurate, of this animal. It has been composed not artificially by some itinerant peddler, but truly brought forth into the light of day by God and by Nature. We wish to show it as an illustration to the eyes of the curious reader that he may contemplate it, just as if it were expressed like words in a document or on a tablet. Thus with perfect liberty we have set before you that which we know with complete certainty, not from a zoological description alone; and thus we have exactly described and elegantly depicted a dragon of this kind, just as it existed.

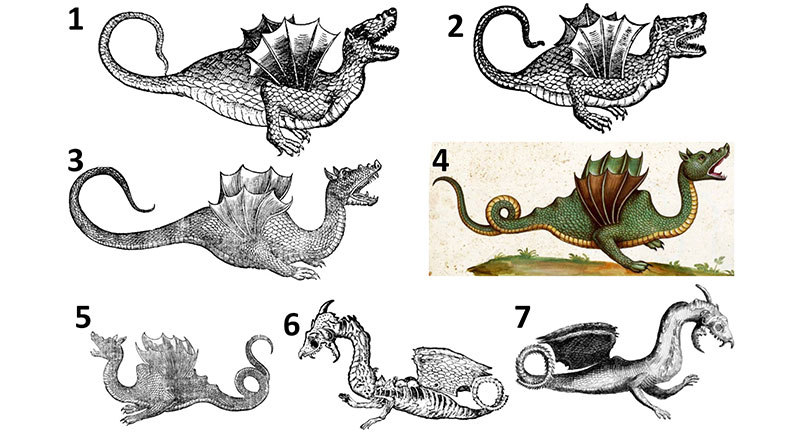

FIGURE 1. Illustrations of the three dragons investigated here. 1.1. Belon’s dragon, from Belon (1588). 1.2. Belon’s dragon, from Gessner (1589). 1.3. Belon’s dragon, from Aldrovandi (1640). 1.4. Aldrovandi’s dragon, from the Tavole di animale (Biblioteca Universitaria di Bologna, 2013). 1.5. Aldrovandi’s dragon, from Aldrovandi (1640). 1.6. Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Faber (1651). 1.7. Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Kircher (1664).

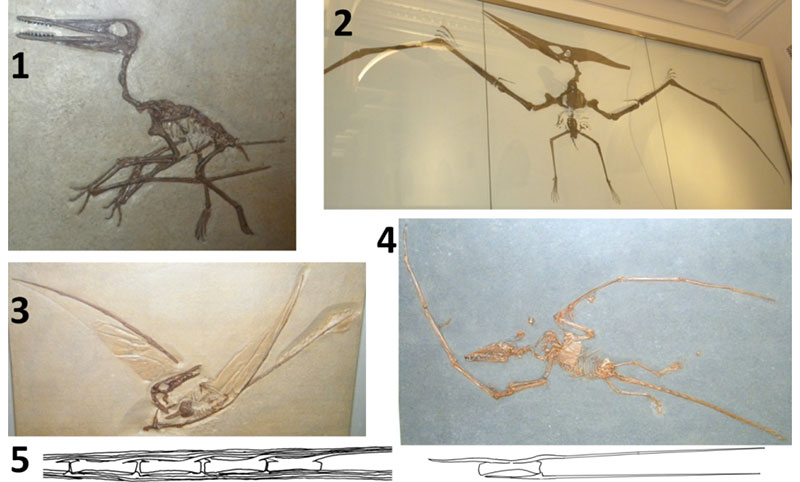

FIGURE 2. Skeletons of pterosaurs. 2.1. AMNH castof Pterodactylus antiquus. 2.2. Pteranodon longiceps, AMNH (American Museum of Natural History, New York City, New York) 6158. 2.3. AMNH cast of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri. 2.4. AMNH cast of Campylognathoides zitteli. 2.5. Vertebrae of the long-tailed pterosaur Rhamphorhychus muensteri in right lateral view, modified from Wellnhofer (1975); left: series of caudal vertebrae, showing the network of elongate dorsal and ventral processes that stiffens the tail; right: a single caudal vertebra and hemal arch, showing the elongate dorsal and ventral processes that contribute to the network.

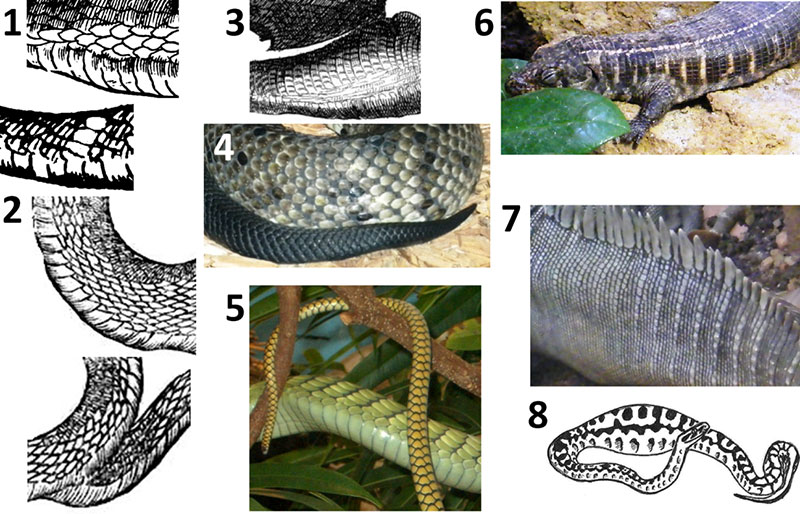

FIGURE 3. Comparison of the skin of the three dragons to that of snakes and lizards. 3.1. Belon’s dragon, scales of torso (above) and tail (below, with original cross-hatching removed from one scale row for clarity), from Belon (1588). 3.2. Aldrovandi’s dragon, skin of neck (above) and tail (below, rotated clockwise relative to its position in Aldrovandi’s original illustration), from Aldrovandi (1640). 3.3. Torso skin of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Kircher (1664). 3.4. Agkistrodon piscivorus (cottonmouth), live specimen at Reptile Lagoon (Hamer, South Carolina), showing the diagonal scale rows that are present both on the torso and the tail in snakes; note that the scale rows are diagonal on both torso and tail in Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons. 3.5. Dendroaspis viridis (western green mamba), live specimen at Riverbanks Zoo (Columbia, South Carolina), showing diagonal torso and tail scale rows, and showing the transversely elongated ventral scutes that are unique to snakes; note that the three dragons also have ventral scutes of this type. 3.6. Torso of Gerrhosaurus validus (giant plated lizard), live specimen at United States National Zoo (Washington, D.C.), showing that the scale rows of the torso are vertical, as in many lizards; note that the scale rows are also vertical on the torso of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon. 3.7. Tail of Cyclura lewisi (blue iguana), live specimen at United States National Zoo, showing that the scale rows are vertical, as in the tails of most lizards; note that the scale rows are not vertical on the tails of Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons. 3.8. Juvenile Python sebae (African rock python) after a large meal, drawn from a photo by P.S., showing that in a snake the torso skin distends without tearing when a large object is in the digestive tract; note the similarity with the bulbous torsos of Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons in Figure 1.

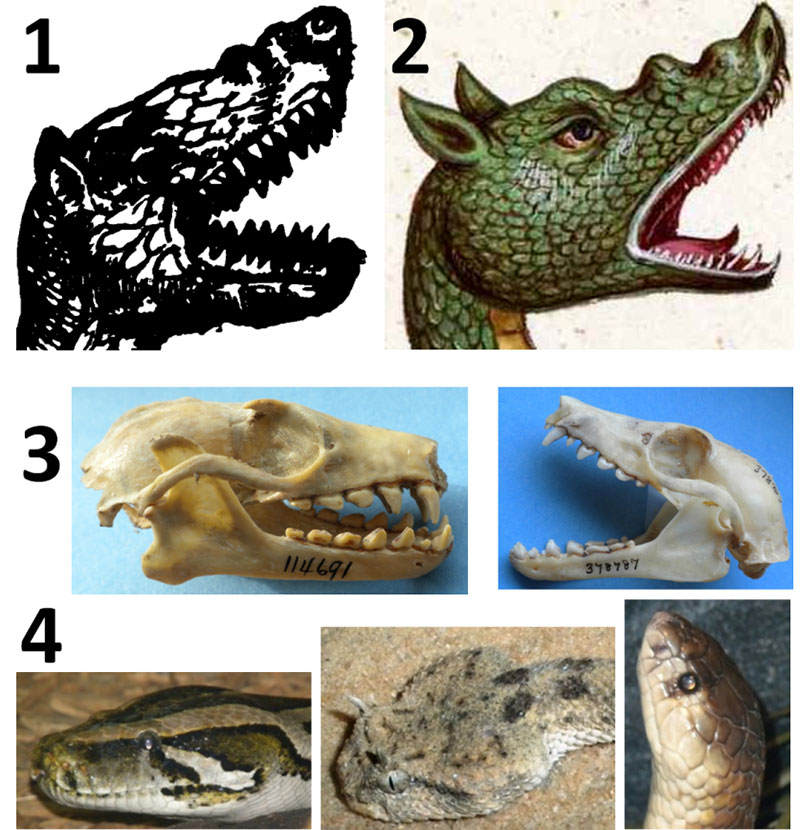

FIGURE 4. Heads of Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons compared with those of African fruit bats and with those of snakes. 4.1. Belon’s dragon. 4.2. Aldrovandi’s dragon. 4.3. left to right: Rousettus aegyptiacus (Egyptian fruit bat), USNM (United States National Museum, Washington, D.C.) 114691; Eidolon helvum (straw-colored fruit bat) , USNM 378787. 4.4. Snakes (live specimens at Reptile Lagoon, Hamer, South Carolina), showing that the eye is closer to the tip of the snout than in Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons; left to right: Python molurus (Asian rock python), Cerastes cerastes (Sahara horned viper), Naja haje (Egyptian cobra).

FIGURE 5. Comparison of the wings of Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s dragons to pterosaur wings, bat wings, and the pectoral fins of flying gurnards and a sea robin. 5.1. Underside of right wing of Belon’s dragon. 5.2. Underside of left wing of Aldrovandi’s dragon. 5.3. Dactylopterus volitans (flying gurnard), AMNH 44472 in ventral view, with right pectoral fin partially spread. 5.4. Partially-spread pectoral fin of D. volitans , AMNH 52457. 5.5. Partially-spread pectoral fin of D. volitans , AMNH 44472; note that as in the two dragons’ wings, the fin is narrow at the base, widens distally, and has multiple internal struts that proceed from the shoulder distally. 5.6. Model of D. volitans with pectoral fins fully spread; note the resemblance to the two dragon’s wings, both in the scalloped margin of the fins and the width of the soft tissue between the internal struts. 5.7. Illustration of D. volitans from Bloch (1790), showing the life colors of the fish; note that the colors and spotted pattern fade after death, as shown in 5.3-5, explaining the lack of spots in Belon’s and Aldrovandi’s illustrations. 5.8. Model of Prionotus evolans (striped sea robin), showing that despite similar morphology in the pectoral fin, the spread of soft tissue between the internal struts is much less than in the two dragons and D. volitans. 5.9. Antrozois pallidus (pallid bat), NCSM (North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, Raleigh, North Carolina) 5314, showing that in bats the wing has only four internal struts, two of which are closely appressed so that there appear to be only three; note that the wings of the two dragons have more internal struts than this. 5.10. AMNH cast of Rhamphorhynchus muensteri with soft-tissue impressions, showing that the wing of a pterosaur is vastly different in shape from that of the two dragons and has only one internal strut.

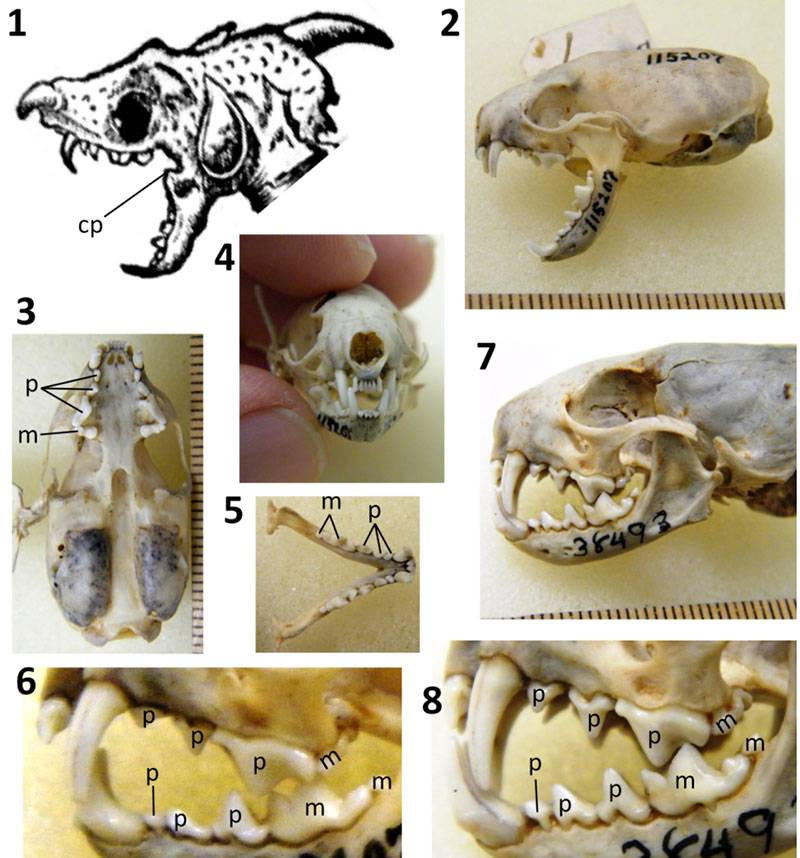

FIGURE 6. Skull of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon and those of weasels (Mustela). All photos but 6.6. and 6.8 are to scale (rulers are marked in mm). Note that in Mustela the upper molar is hidden by the much larger third premolar, and the second lower molar is tiny, making both easy to miss. 6.1. Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Faber (1651). 6.2. Mustela nivalis (common weasel), USNM 115207, lateral view; note the resemblance to the dragon’s skull. 6.3. M. nivalis, USNM 115207, palatal view. 6.4. M. nivalis, USNM 115207, anterior view, showing that the incisors match Faber’s description. 6.5. M. nivalis mandible, USNM 115207, occlusal view. 6.6. M. nivalis, USNM 115207, enlargement of dentition. 6.7. M. erminea (stoat), USNM 38493. 6.8. M. erminea, USNM 38493, enlargement of dentition. cp = coronoid process; m = molar; p = premolar.

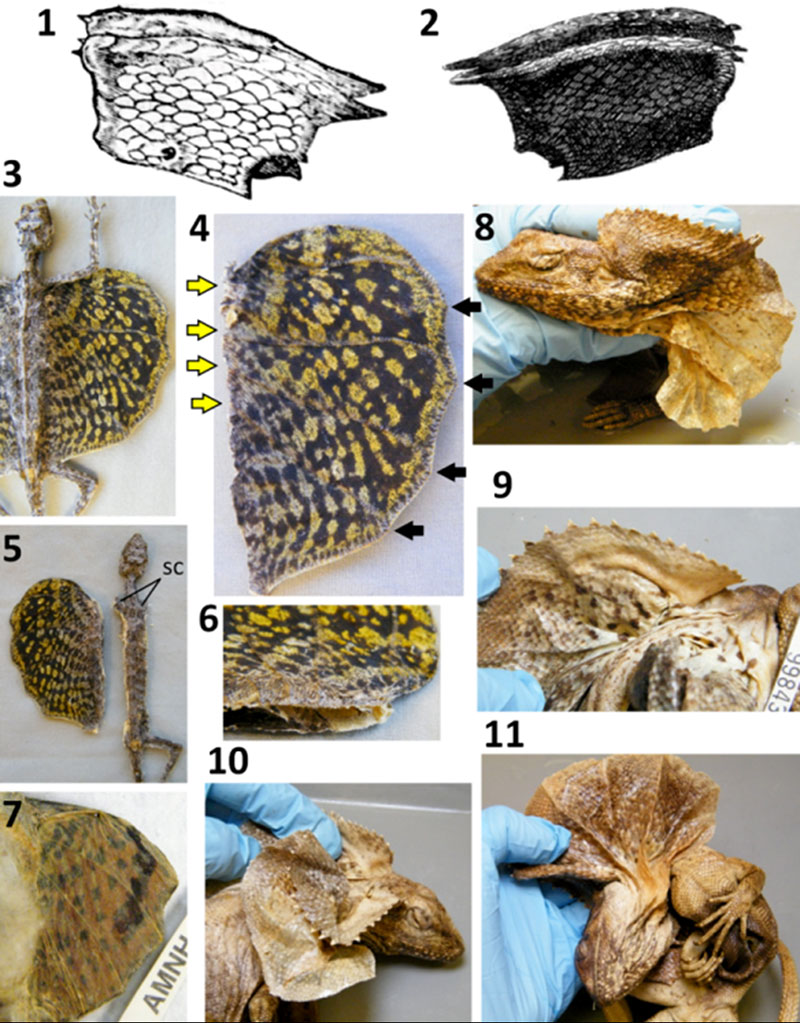

FIGURE 7. Wings of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon compared with patagium of Draco (flying lizards) and frill of Chlamydosaurus kingii (frilled lizard). 7.1. Wings of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Faber (1651). 7.2. Wings of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Kircher (1664). 7.3. Draco haematopogon (personal collection of P.S.), showing spots on patagium. 7.4. Detached right patagium of specimen in 7.3, with yellow arrows showing proximal ends of ribs and black arrows showing distal tips of ribs. 7.5. Same specimen after detachment of left patagium plus part of the body wall. 7.6. Internal view of detached left patagium, showing that no clawlike structures are present. 7.7. Draco maximus, AMNH 29976, ventral view, showing spots on patagium. 7.8-11. Chlamydosaurus kingii, showing projections at edge of frill that resemble the claws on Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, showing the three strong creases in the ventral half of the frill ( 7.8, 7.10-11: AMNH 86512), and showing spots on the frill of one specimen ( 7.9: AMNH 99843).

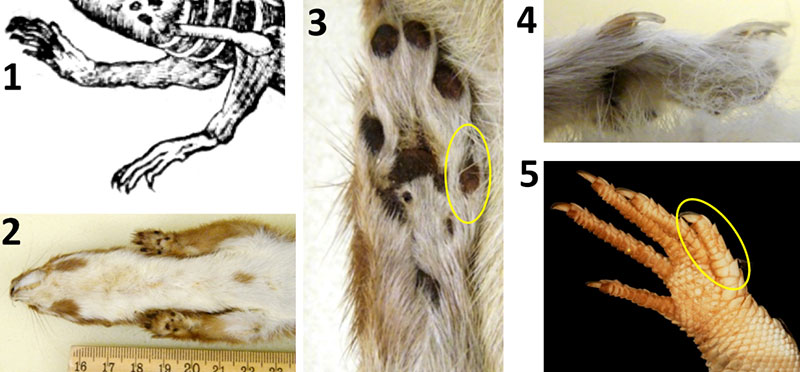

FIGURE 8. Hands of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon compared with those of a common weasel (Mustela nivalis) (USNM 115211) and an ocellated lizard (Lacerta lepida) (MCZ [Museum of Comparative Zoology, Cambridge, Massachusetts] R-29871). Thumbs are circled in yellow. 8.1. Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Faber (1651). 8.2. M. nivalis, showing that the size of the hand relative to the head resembles that in Cardinal Barberini’s dragon (see Figure 1.5-6). 8.3. M. nivalis, showing that the thumb is shorter than the other fingers. 8.4. M. nivalis, showing curvature of the finger claws. 8.5. L. lepida, showing that the thumb is shorter than the other fingers.

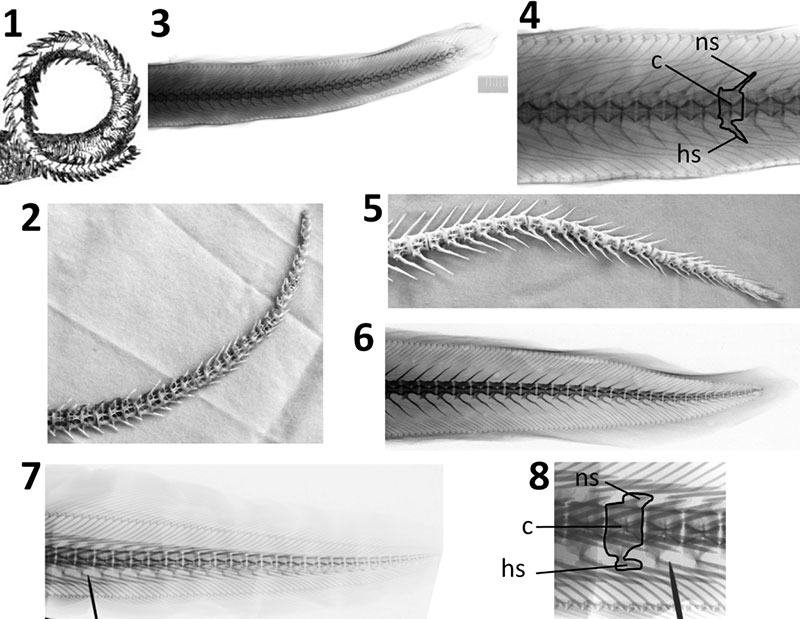

FIGURE 9. Tail of Cardinal Barberini’s dragon compared with the tails of eels. In the photos and x-ray images of eels, including the close-ups, the anteriormost complete vertebra shown is the thirtieth vertebra from the tip of the tail, to facilitate comparison with Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, on which Faber counted 30 tail vertebrae (Appendix 1). 9.1. Cardinal Barberini’s dragon, from Kircher (1664). 9.2. Tail skeleton of Anguilla rostrata (American eel) (NCSM 69208), showing the shortness of the neural and hemal spines in Anguilla, as in Cardinal Barberini’s dragon. 9.3. X-ray image of Anguilla anguilla (European eel) (MCZ 9244), the one Mediterranean species of Anguilla. 9.4. Close-up of 9.3 with one vertebra outlined, showing that the neural and hemal spines are short relative to centrum height. 9.5. Tail skeleton of Conger oceanicus (American conger) (NCSM 69209), showing the great length of the neural and hemal spines. 9.6. Conger conger (European conger) (MCZ 9293), showing that in the one Mediterranean species of Conger, the neural and hemal spines are longer relative to the centrum than they are in Anguilla, and in fact are longer than the height of the centrum. 9.7. Muraena helena (Mediterranean moray) (MCZ 9293). 9.8. Close-up of 9.7, with one vertebra outlined, showing that the shapes of the neural and hemal arches are not simple spikes and therefore do not match Cardinal Barberini’s dragon. c = centrum; hs = hemal spine; ns = neural spine.

Investigation of claims of late-surviving pterosaurs: the cases of the winged dragons of Belon, Aldrovandi, and Cardinal Barberini

Plain Language Abstract

Here we investigate claims that three taxidermic specimens of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries were recently-killed pterosaurs. We compared drawings and descriptions of the specimens with pterosaurs. We found that in all three specimens, all regions of the body are inconsistent with pterosaur anatomy. Belon's and Aldrovandi's dragons are decapitated snakes with attached mammal heads. Their wings are the pectoral fins of a species of fish called a flying gurnard. The dragon illustrated by Faber includes the skull of a weasel, the belly skin of a snake, and the tail skeleton of an eel. These "proofs" of human-pterosaur coexistence are now revealed to be hoaxes.

Resumen en Español

Investigación de las declaraciones sobre la existencia de pterosaurios vivientes: los casos de dragones alados de Belon, Aldrovandi y el cardenal Barberini

Se investigan las declaraciones sobre la existencia de pterosaurios vivientes en los siglos XVI y XVII. En 1557, 1640, y 1651 los naturalistas europeos Pierre Belon, Ulisse Aldrovandi y Giovanni Faber, respectivamente, publicaron ilustraciones de ejemplares alados y bípedos que habían sido disecados y montados. Algunos autores creacionistas de la Tierra joven declaran que estos ejemplares eran pterosaurios recién muertos. Los dibujos y las descripciones son lo suficientemente detallados como para poner a prueba la hipótesis del pterosaurio, así como la hipótesis alternativa de que los especímenes disecados fueron elaborados con partes de diferentes animales. Sin embargo, hasta ahora, nadie ha investigado estos tres casos con el objetivo de poner a prueba estas hipótesis, lo cual se hace en la presente investigación. Mediante la comparación de las muestras con los pterosaurios, se observó que todas las regiones del cuerpo en las tres muestras son inconsistentes con la anatomía de un pterosaurio. La comparación con animales actuales revela que los dragones de Belon y de Aldrovandi corresponden a serpientes decapitadas a las que se unieron cabezas de mamífero. Sus alas son aletas pectorales de alones (Dactylopterus volitans). Sus "patas" son extremidades anteriores de conejos o cánidos cubiertas con mangas de piel de reptil. El dragón ilustrado por Faber, propiedad del cardenal Francesco Barberini, incluye el cráneo de una comadreja (Mustela nivalis), la piel del vientre de una serpiente, la piel dorsal y lateral de un lagarto, y el esqueleto de la cola de una anguila (Anguilla anguilla). Estos engaños se unen ahora a la lista de las desacreditadas "pruebas" de la convivencia entre humanos y pterosaurios.

Palabras clave: Pterosauria; creacionismo de la Tierra joven; Ulisse Aldrovandi; Pierre Belon; Giovanni Faber; engaño

Traducción: Enrique Peñalver

Résumé en Français

Enquête sur les revendications de ptérosaures survivants tardifs: les cas des dragons ailés de Belon, d'Aldrovandi, et du cardinal Barberini

Nous étudions ici les revendications que les ptérosaures ont survécu jusqu'aux XVIe et XVIIe siècles. En 1557, 1640, et 1651, les naturalistes européens Pierre Belon, Ulisse Aldrovandi, et Giovanni Faber, respectivement, ont publié des illustrations de spécimens ailés, bipèdes qui avaient été empaillés et montés. Certains auteurs créationnistes jeune-Terre récents affirment que ces spécimens sont des ptérosaures récemment tués. Les dessins et les descriptions sont suffisamment détaillés pour tester l'hypothèse ptérosaure ainsi que l'hypothèse alternative que ces spécimens soient des composites de taxidermie de parties d'animaux différents. Toutefois, précédemment, personne n'a enquêté sur ces trois cas ou tenté de tester ces hypothèses. Nous rapportons ici une enquête dans laquelle ces hypothèses sont testées. En comparant les spécimens avec des ptérosaures, nous avons constaté que dans les trois spécimens, toutes les régions du corps sont incompatibles avec l'anatomie de ptérosaure. La comparaison avec des animaux existants révèle les dragons de Belon et d'Aldrovandi sont des serpents décapités avec des têtes de mammifères attachés. Leurs ailes sont les nageoires pectorales des grondins volants (Dactylopterus volitans). Leurs «jambes» sont les membres antérieurs de lapins ou de canidés à l'intérieur de manches en peau de reptile. Le dragon illustré par Faber et détenue par le cardinal Francesco Barberini comprend le crâne d'une belette (Mustela nivalis), la peau du ventre d'un serpent, la peau dorsale et latérale d'un lézard, et le squelette de la queue d'une anguille (Anguilla anguilla). Ces canulars rejoignent maintenant la liste des «preuves» discréditées de la coexistence homme-ptérosaure.

Mots-clés: Pterosauria; jeune-Terre créationnisme; Ulisse Aldrovandi; Pierre Belon; Giovanni Faber; canular

Translator: Kenny J. Travouillon

Deutsche Zusammenfassung

Untersuchung von Behauptungen über überlebende Pterosaurier: Die Sache mit den geflügelten Drachen von Belon, Aldrovandi und Kardinal Barberini

Wir untersuchen hier Behauptungen, dass Pterosaurier bis in das sechzehnte und siebzehnte Jahrhundert überlebt haben. 1557, 1640 und 1651 veröffentlichten die europäischen Naturalisten Pierre Belon, Ulisse Aldrovandi und Giovanni Faber Zeichnungen von geflügelten zweibeinigen Tieren, die präpariert und aufgestellt waren. Einige der heutigen Young-Earth Kreationisten behaupten, dass diese Exemplare kürzlich getötete Pterosaurier seien. Die Zeichnungen und Beschreibungen sind detailliert genug um die Pterosaurier-Hypothese zu testen, ebenso wie die Alternativhypothese dass die Stücke taxidermische Montagen aus Teilen verschiedener Tiere sind. Jedoch hat bis jetzt noch niemand diese drei Fälle untersucht oder hat versucht sie zu prüfen. Wir veröffentlichen hier eine Analyse die diese Hypothesen untersucht. Bei einem Vergleich der Stücke mit Pterosauriern fanden wir heraus, dass die Körperteile bei allen drei Stücken nicht mit der Pterosaurieranatomie übereinstimmen. Vergleiche mit heutigen Tieren zeigen, dass die Drachen von Belon und Aldrovandi geköpfte Schlangen mit angefügten Säugetierköpfen sind. Die Flügel bestehen aus den Brustflossen des fliegenden Knurrhahns (Dactylopterus volitans) und die „Beine" sind die Vorderbeine von Kaninchen oder Hunden in Reptilhaut-Hüllen. Der von Faber abgebildete und Kardinal Francesco gehörende Drache besteht aus dem Schädel eine Wiesels (Mustela nivalis), der Bauchhaut einer Schlange, der dorsalen und lateralen Haut einer Eidechse und dem Schwanzskelett eines Aals (Anguilla anguilla). Diese Fälschungen schließen sich nun der Liste der diskreditierten „Beweise" einer Koexistenz von Menschen und Pterosauriern an.

Schlüsselwörter: Pterosauria; Young-Earth Kreationismus; Ulisse Aldrovandi; Pierre Belon; Giovanni Faber; Fälschung

Translator: Eva Gebauer

Arabic

Translator: Ashraf M.T. Elewa

-

-

PE: An influential journal

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journals

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journalsArticle number: 27.2.2E

July 2024

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei