Volume 28.2

May–August 2025

Full table of contents

ISSN: 1094-8074, web version;

1935-3952, print version

Recent Research Articles

See all articles in 28.2 May-August 2025

See all articles in 28.1 January-April 2025

See all articles in 27.3 September-December 2024

See all articles in 27.2 May-August 2024

Interested in submitting a paper to Palaeontologia Electronica?

Click here to register and submit.

Article Search

Brian F. Platt.

Brian F. Platt.

Department of Geology and Geological Engineering,

University of Mississippi,

120A Carrier Hall,

University, Mississippi 38677

USA

bfplatt@olemiss.edu

Brian F. Platt is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Geology and Geological Engineering at the University of Mississippi. He received his PhD in geology from the University of Kansas in 2012. His area of specialization is continental ichnology and much of his research involves the integration of ichnology, paleopedology, and sedimentary geology to interpret paleoenvironments and paleoclimates. He also enjoys any opportunities to conduct neoichnological studies to better inform interpretations of the trace-fossil record. Previous and ongoing projects include investigations of dinosaur tracks and other trace fossils in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation (Wyoming and Utah) and the Lower Cretaceous De Queen Formation (Arkansas), ichnology and stratigraphy of calcretes and paleosols in the Neogene Ogallala Formation (Kansas), ichnological applications of three-dimensional technologies, and elephant neoichnology.

TABLE 1. Quantitative data from 3D models of armadillo pit casts. DIH = diameter/height ratio; V:SA = volume/surface area ratio; RC = relative compactness; VE = volume exploited; C = conicality.

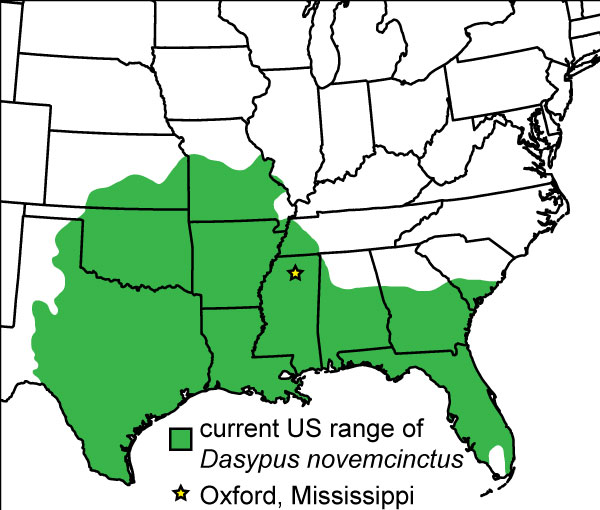

FIGURE 1. Partial map of the United States showing the northern limit of the range of D. novemcinctus and the study area in Lafayette County, MS.

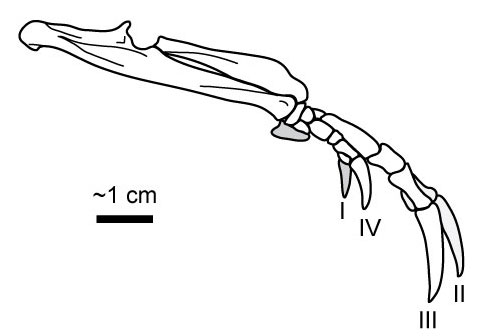

FIGURE 2. Skeletal anatomy of the distal right forelimb of D. novemcinctus (Modified from Vaughan, 1972); approximate scale based on adult forelimb measurements from Costa and Vizcaíno (2010).

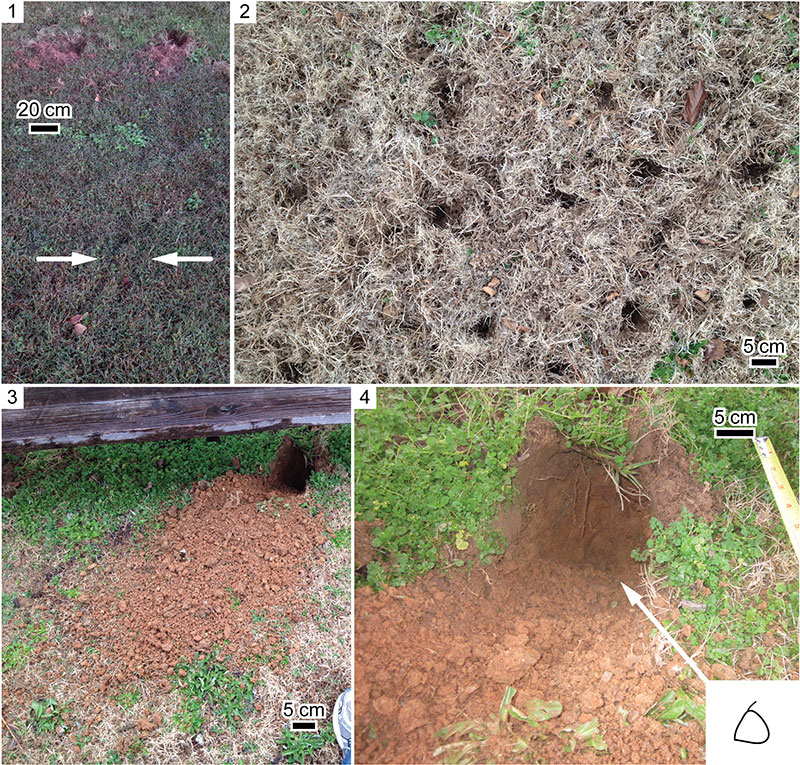

FIGURE 3. Overview of armadillo foraging traces. 1) Paired, linear trails in grass (arrows) associated with soil pits. 2) Pits in grass-covered soil surface. 3) Type 2 burrow and associated sediment wedge. 4) Close-up of Type 2 burrow in part 3. Note rounded triangular cross-section of apex (inset).

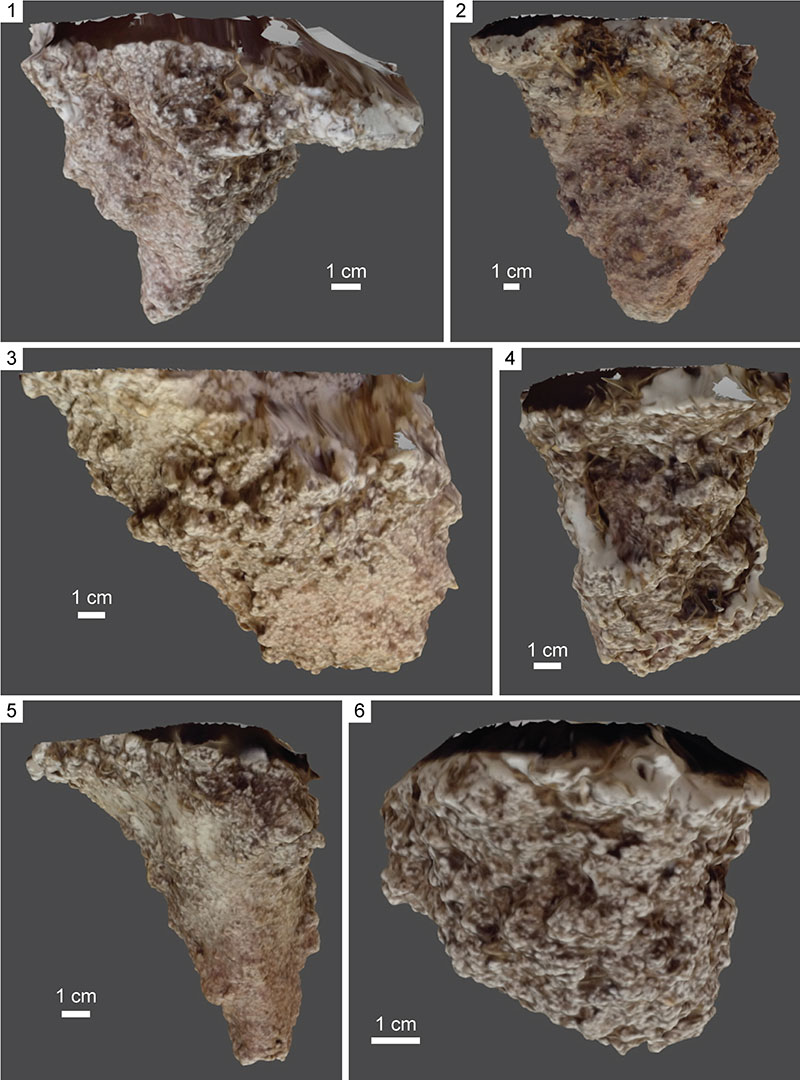

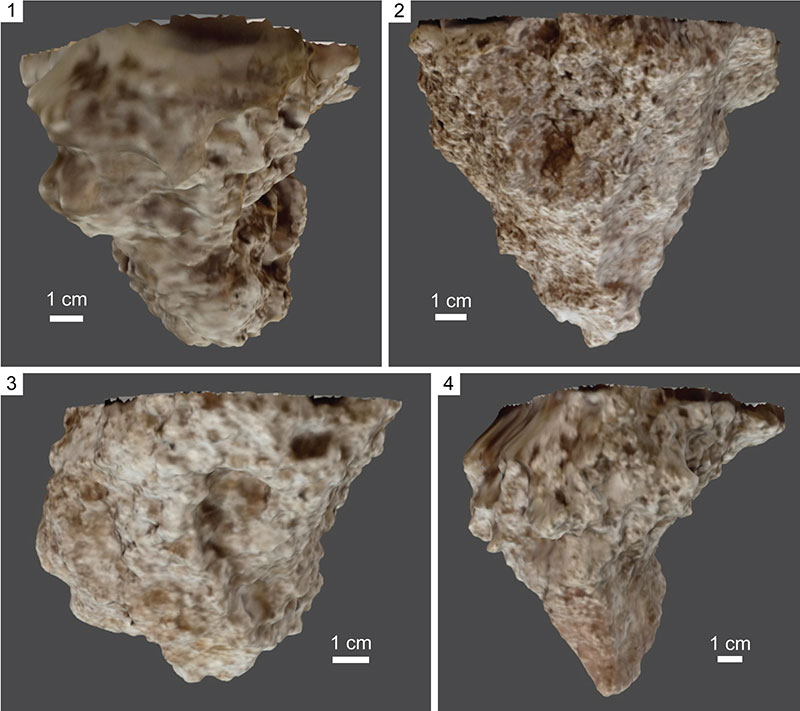

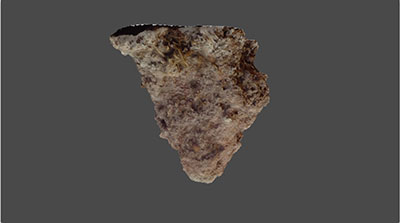

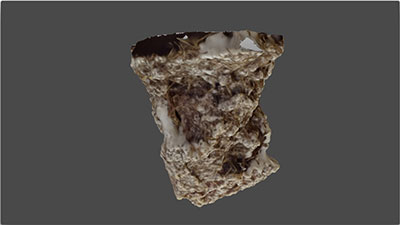

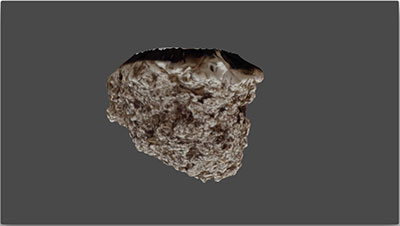

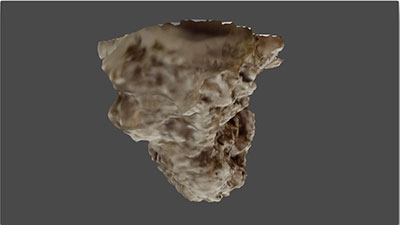

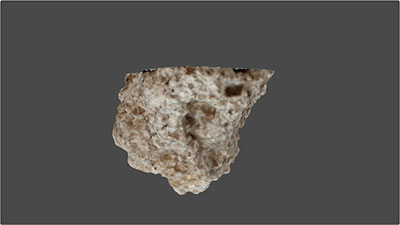

FIGURE 4. Animations (see online) showing rotation of textured 3D models of plaster casts of armadillo pits. Animations were created in Blender (Stichting Blender Foundation, 2013); light source is a hemispherical lamp aligned to camera view. Pit numbers correspond to numbers in Table 1. 1) Pit 1 (animation). 2) Pit 2 (animation). 3) Pit 3 (animation). 4) Pit 4 (animation). 5) Pit 5 (animation). 6) Pit 6 (animation).

FIGURE 5. Animations (see online) showing rotation of textured 3D models of plaster casts of armadillo pits. Animations were created in Blender (Stichting Blender Foundation, 2013); light source is a hemispherical lamp aligned to camera view. Pit numbers correspond to numbers in Table 1. 1) Pit 7 (animation). 2) Pit 8 (animation). 3) Pit 9 (animation). 4) Pit 10 (animation).

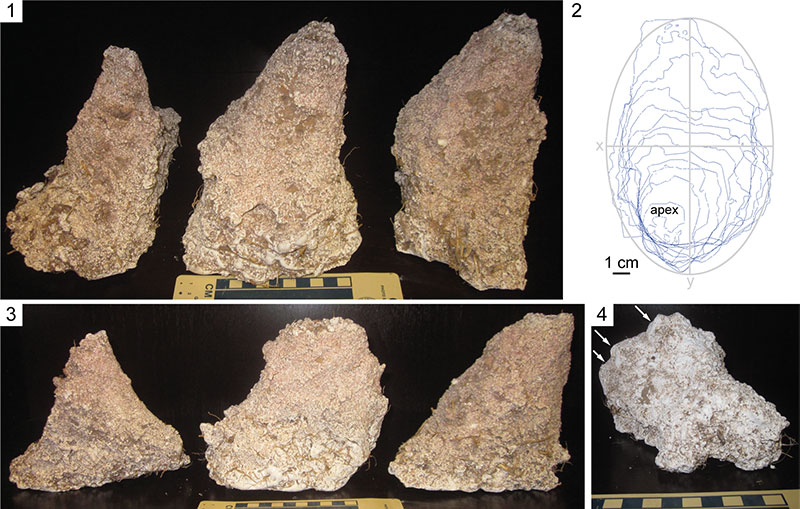

FIGURE 6. Qualitative observations of pit casts. Note that all pits are displayed upside down for stability. 1) Three plaster casts of pits (from left to right: pits 5, 3, and 2); view parallel to long axes. Note asymmetry. 2) Contour map (contour interval = 1.2 cm) of a pit cast (pit 2) with superimposed ellipse. Note how the pit is asymmetrical about the x and y axes of the ellipse and the apex of the pit falls into a quadrant of the ellipse. 3) Three plaster casts of pits from part 1 (from left to right: pits 5, 3, and 2) oriented perpendicular to long axes. Note asymmetry. 4) Plaster cast of pit (pit 9) with tiered wall (arrows). See Figure 7.4-5 for more detail.

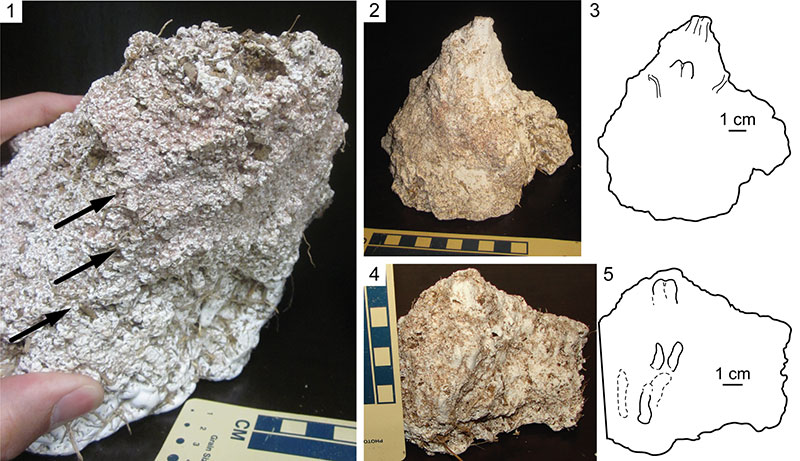

FIGURE 7. Surficial morphology of plaster casts of soil pits. All are shown upside down relative to original orientation. 1) Three parallel groove casts oriented roughly parallel to vertical axis of pit. 2) Plaster cast of soil pit (pit 8) with isolated, curved groove casts and paired groove casts. 3) Line drawing of pit cast in part 2. 4) Pit cast from Figure 6.4 (pit 9) oriented to show paired groove casts associated with each wall tier. 5) Line drawing of pit cast from part 4.

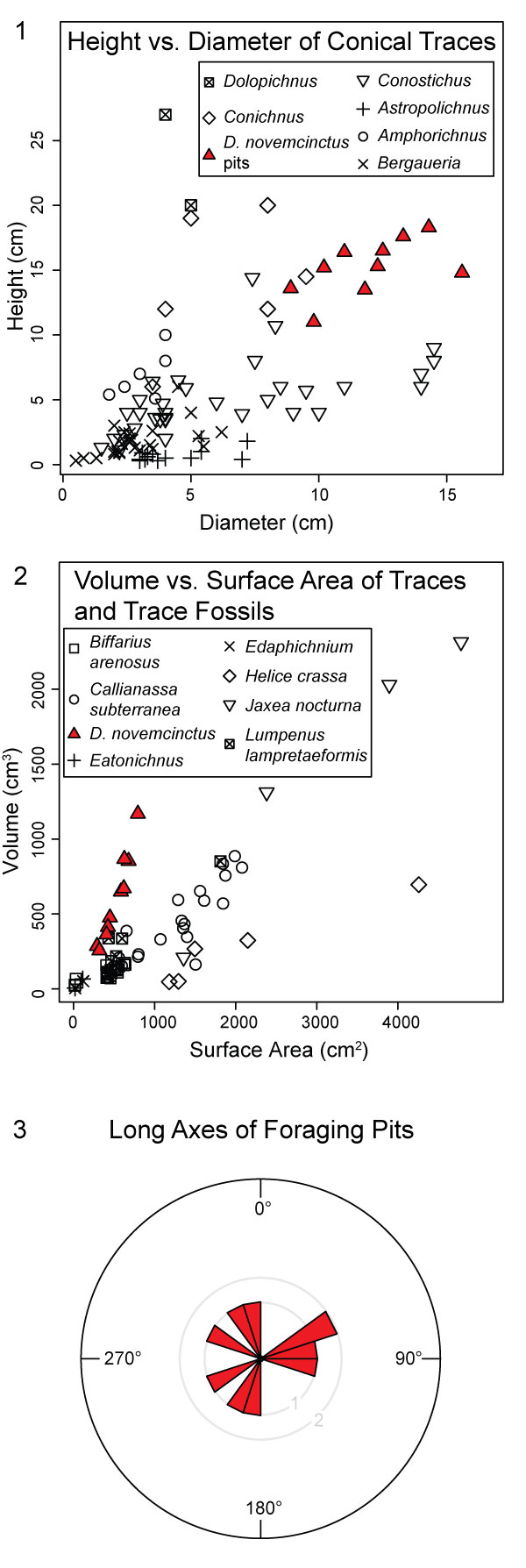

FIGURE 8. Graphs of armadillo pit data. 1) Scatterplot of height vs. diameter for armadillo pits. Data for conical trace fossils from Pemberton et al. (1988) provided for comparison. 2) Scatterplot of volume vs. surface area of armadillo pit casts. Data from other modern traces and trace fossils from Platt et al. (2010) provided for comparison. 3) Rose diagram showing orientations of foraging pit long axes.

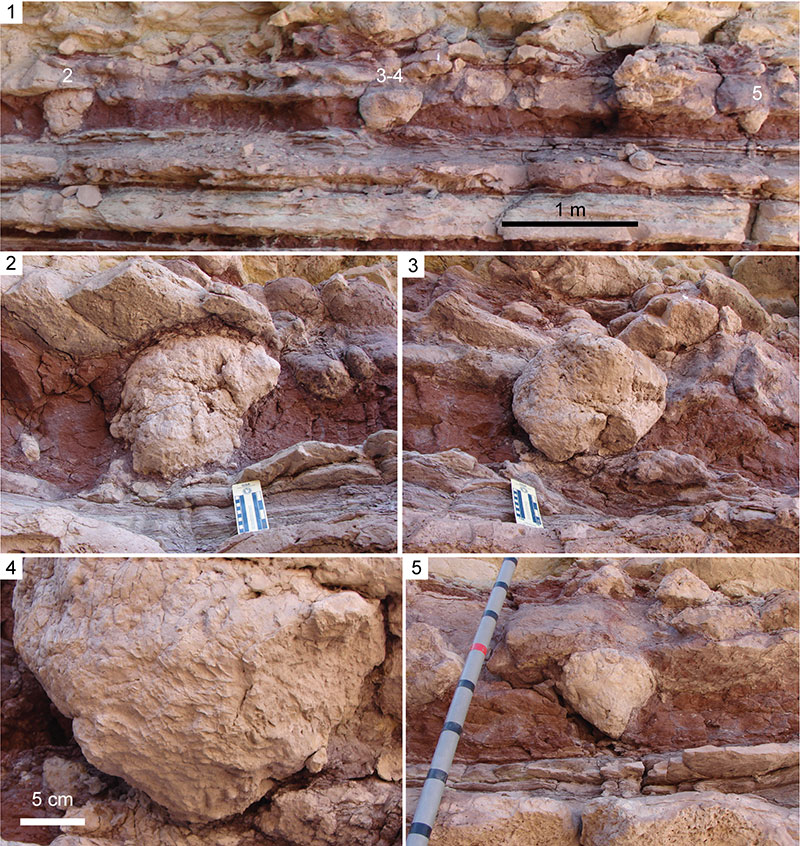

FIGURE 9. Possible examples of fossil vertebrate foraging pits from the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. 1) Composite image showing three conical features associated with a paleosol in an outcrop of the Salt Wash Member in Garfield County, Utah. Note that all three originate from the upper bedding plane. 2) Close-up of left-most conical trace fossil in part 1. 3) Close-up of center conical trace fossil in part 1. 4) Close-up of conical trace fossil in part 3. Note broken apex and sets of parallel groove casts on base. 5) Close-up of right-most trace fossil in part 1. Jacob staff is marked in decimeters.

ANIMATION 1. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 1. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 2. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 2. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 3. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 3. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 4. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 4. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 5. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 5. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 6. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 6. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 7. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 7. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 8. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 8. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 9. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 9. Click on image to run animation.

ANIMATION 10. 360 degree rotation of digital model of pit 10. Click on image to run animation.

The foraging pits of the nine-banded armadillo, Dasypus novemcinctus (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae), and implications for interpreting conical trace fossils

Plain Language Abstract

The nine-banded armadillo is the only species that lives in the United States, where it is commonly viewed as a pest due to its persistent digging behavior and potential for transmitting disease (e.g., leprosy). The purpose of much of the armadillo's digging is to forage for prey below the soil surface. This foraging behavior creates conical pits that effectively mix soils, contribute to soil erosion, and have the potential to be preserved as trace fossils in ancient soils (paleosols). This study is the first detailed investigation of the morphology of modern armadillo foraging pits. The pits are generally conical in shape, and many have scratch marks on their surfaces, including distinctive paired grooves resulting from the two elongated middle digits on the armadillo's forelimbs. The results of this study will improve interpretations of large conical trace fossils in terrestrial settings. Because modern armadillos have specific environmental and climatic requirements, the identification and mapping of ancient foraging pits can be used to infer ancient environmental and climatic conditions.

Resumen en Español

Los hoyos de forrajeo del armadillo de nueve bandas, Dasypus novemcinctus (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae), y las implicaciones para la interpretación de huellas fósiles cónicas

El armadillo de nueve bandas (Dasypus novemcinctus) es un cavador de madrigueras bien conocido, pero los individuos pasan la mayor parte de su tiempo en la superficie externa forrajeando organismos del suelo mediante la realización repetitiva de hoyos en la superficie del suelo. En los estudios icnológicos se ha prestado poca atención a estos hoyos de forrajeo a pesar de su gran prevalencia en el área de distribución geográfica de los armadillos actuales, lo que implica que deben tener un registro fósil icnológico en paleosuelos que debe remontarse por lo menos hasta el Paleoceno. La presente investigación describe los hoyos de forrajeo producidos por D. novemcinctus con implicaciones para el reconocimiento e interpretación de trazas fósiles cónicas similares. Las observaciones de campo revelaron una asociación compuesta por madrigueras de habitación de gran diámetro (41 cm de ancho), tres relativamente cortas, por madrigueras de refugio rectas (hasta 19 cm de ancho y 38 cm de largo), y por abundantes hoyos de forrajeo de tamaños diversos (hasta 18 cm de ancho y 14,5 cm de profundidad). Los moldes de yeso de hoyos de forrajeo mostraron que la mayoría eran conos asimétricos, orientados verticalmente, que se estrechaban de forma elíptica hacia abajo (anchura>profundidad), con paredes con hoyuelos de forma suave a tosca y con usuales surcos paralelos y alargados, aislados surcos de forma curva, y distintivos surcos pareados, originados por la acción de rascado del alargado par de dígitos medios de la extremidad anterior. Se utilizan modelos digitales de moldes de yeso para cuantificar varios aspectos, entre ellos uno nuevo, la conicidad. La compacidad relativa y el volumen considerados indican que los hoyos superficiales son más eficientes para la búsqueda de alimento del suelo que las madrigueras subterráneas. El reconocimiento de fósiles de hoyos de forrajeo de armadillos permitiría realizar interpretaciones paleoambientales y paleoclimáticas que serían análogas a las condiciones de los hábitats de los armadillos actuales. Las trazas fósiles cónicas del Jurásico Superior de la Formación Morrison son ejemplos potenciales de antiguos hoyos de forrajeo producidos por vertebrados, aunque no son atribuibles a armadillos debido a su edad.

Palabras clave: icnología; neoicnología; conicidad; Formación Morrison; suelos; paleosuelos

Traducción: Enrique Peñalver

Résumé en Français

Les fosses d'alimentation du tatou à neuf bandes, Dasypus novemcinctus (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae), et implications pour l'interprétation des fossiles traces coniques

Le tatou à neuf bandes (Dasypus novemcinctus) est un fouisseur bien connu, mais les individus passent la majorité de leur temps au-dessus du sol à la recherche de nourriture provenant d'organismes du sol en creusant à plusieurs reprises des fosses à travers la surface du sol. Peu d'attention ichnologique a été donnée à ces fosses d'alimentation, même si leur grande prévalence au sein de l'aire de répartition géographique des tatous existants implique qu'ils pourraient avoir un registre de fossile trace dans les paléosols remontant à au moins le Paléocène. Cette recherche décrit les fosses d'alimentation construites par D. novemcinctus avec des implications pour la reconnaissance et l'interprétation des fossiles traces similaires coniques. Les observations de terrain ont donné une association entre un terrier d'habitation de grand diamètre (41 cm de large), trois terriers d'abris, droits, relativement courts (jusqu'à 19 cm de large et 38 cm de long), et plusieurs fosses d'alimentation de diverses dimensions (jusqu'à 18 cm de large et 14,5 cm de profondeur). Les moulages en plâtre des fosses d'alimentation ont montré que la plupart étaient asymétrique, orienté verticalement, en forme de cônes elliptique pointé vers le bas et effilé (largeur> profondeur), avec des parois lisse à grossièrement alvéolées et communément allongé, avec des rainures parallèles, des rainures incurvées isolées, et des rainures appariées distinctes, résultat de grattage avec les deux doigts allongés du milieu de la patte antérieure. Les modèles numériques des moulages en plâtre sont utilisées pour quantifier plusieurs aspects, y compris une nouvelle propriété, conicité. La compacité relative et le volume exploité indiquent que les fosses de surface sont plus efficaces pour se nourrir du sol que des terriers. La reconnaissance des fossiles de fosses d'alimentation de tatou permettrait des interprétations paléoenvironnementales et paléoclimatiques analogues aux habitats et à la portée des tatous existants. Les fossiles traces coniques dans la Formation de Morrison du Jurassique Supérieure sont des exemples potentiels de fosses d'alimentation anciennes de vertébrés, même s'ils ne sont pas attribuables à des tatous en raison de leur âge.

Mots-clés: ichnologie; néoichnologie; conicité; Formation de Morrison; sols; paléosols

Translator: Kenny J. Travouillon

Deutsche Zusammenfassung

Die Futtersuche-Gruben des Neunbinden-Gürteltiers, Dasypus novemcinctus (Mammalia: Xenarthra: Dasypodidae) und Auswirkungen auf die Interpretation der konischen Spurenfossilien

Das Neunbinden-Gürteltier (Dasypus novemcinctus) ist ein bekannter grabender Organismus aber Individuen verbringen den Großteil ihrer Zeit auf der Erdoberfläche mit dem Suchen nach Bodenorganismen indem sie wiederholt Gruben durch die Oberfläche ziehen. Diesen Futtersuche-Gruben wurde wenig ichnologische Aufmerksamkeit gewidmet obwohl ihre große Verbreitung innerhalb der geografischen Reichweite von heutigen Gürteltieren impliziert dass sie möglicherweise einen Spurenfossilien-Nachweis in Paläoböden zumindest bis ins Paläozän haben. Diese Untersuchung beschreibt die Futtersuche-Gruben von D. novemcinctus mit Auswirkungen auf die Erkennung und Interpretation von ähnlichen konischen Spurenfossilien. Felduntersuchungen lieferten eine Assoziation mit einem Wohnbau mit großem Durchmesser (41 cm breit), drei relativ kurzen geraden Schutzbauten (bis zu 19 cm breit und 38 cm lang) und zahlreichen Futtersuche-Gruben von verschiedener Größe (bis zu 18 cm breit und 14.5 cm tief).

Gipsabgüsse der Futtersuche-Gruben haben gezeigt, dass die meisten asymmetrische, vertikal orientierte, sich nach untern verjüngende elliptische Kegel (Weite > Tiefe) sind, mit glatten bis rauen Wänden und häufig langgestreckten, parallelen Furchen, isolierten gekrümmten Furchen und deutlichen paarigen Furchen, die von den verlängerten mittleren zwei Zehen des Vorderfußes herstammen. Digitale Modelle der Gipsabgüsse machen es möglich einige Aspekte zu quantifizieren, darunter die neue Eigenschaft Konikalität. Die relative Kompaktheit und das erschlossene Volumen weisen darauf hin, dass Oberflächengruben effizienter für die Futtersuche an der Oberfläche sind als unterirdische Bauten. Das Erkennen von fossilen Gürteltier Futtersuche-Gruben würde es ermöglichen Paläoumgebungen und Paläoklimate analog zu den Habitaten und der Verbreitung rezenter Gürteltiere zu interpretieren. Konische Spurenfossilien aus der Oberen Morrison Formation sind potentielle Beispiele für altertümliche Futtersuche-gruben von Vertebraten obwohl sie wegen ihres Alters nicht den Gürteltieren zugeschrieben werden können.

Keywords: Ichnologie; Neoichnologie; Konikalität; Morrison Formation; Böden; Paläoböden

Translator: Eva Gebauer

Arabic

Translator: Ashraf M.T. Elewa

-

-

PE: An influential journal

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journals

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journalsArticle number: 27.2.2E

July 2024

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei