Volume 28.3

September–December 2025

Full table of contents

ISSN: 1094-8074, web version;

1935-3952, print version

Recent Research Articles

See all articles in 28.3 September-December 2025

See all articles in 28.2 May-August 2025

See all articles in 28.1 January-April 2025

See all articles in 27.3 September-December 2024

Interested in submitting a paper to Palaeontologia Electronica?

Click here to register and submit.

Article Search

Mark T. Young. School of GeoSciences, The King’s Buildings, University of Edinburgh, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3FE. myoung5@staffmail.ed.ac.uk

Mark T. Young. School of GeoSciences, The King’s Buildings, University of Edinburgh, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3FE. myoung5@staffmail.ed.ac.uk

Dr Mark Young is an evolutionary biologist and palaeontologist at the University of Edinburgh, UK. His primary research is focused on the taxonomy, phylogeny and evolution of marine crocodylomorphs, in particular Thalattosuchia – the group which includes dolphin-like crocodylian relatives. He completed his MSc degree in Advanced Methods in Taxonomy and Biodiversity at Imperial College London, UK then his PhD at the University of Bristol, UK (both in conjunction with the Natural History Museum London).

Márton Rabi. Department of Earth Sciences, University of Turin, Via Valperga Caluso 35, 10125, Turin, Italy. (2) Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen, Hölderlinstraße 12, 72074 Tübingen, Germany. iszkenderun@gmail.com

Márton Rabi. Department of Earth Sciences, University of Turin, Via Valperga Caluso 35, 10125, Turin, Italy. (2) Institut für Geowissenschaften, University of Tübingen, Hölderlinstraße 12, 72074 Tübingen, Germany. iszkenderun@gmail.com

Márton Rabi obtained his Master degree in geosciences in Budapest, Hungary and his PhD at the University of Tübingen in Germany. His general research interest lies in deep time interactions between environment and diversification in vertebrates. His focus involves the study of various macroevolutionary aspects of extinct Mesozoic and Cenozoic turtles and crocodilians, including morphological transitions, paleoecology and biogeographic history. He is currently a Marie Curie-Train2Move postdoctoral fellow at the Earth Sciences department of the University of Turin in Italy and he is investigating potential environmental drivers of Cretaceous marine turtle evolution.

Mark A. Bell. Department of Earth Sciences, Kathleen-Lonsdale Building, University College London, Gower Street, London, WCIE 6BT. mark.bell521@gmail.com

Mark A. Bell. Department of Earth Sciences, Kathleen-Lonsdale Building, University College London, Gower Street, London, WCIE 6BT. mark.bell521@gmail.com

Mark Bell graduated from the University of Glasgow with a degree in Earth Sciences and then went on to complete a PhD from the University of Bristol which focused on studying the patterns and drivers of body-size evolution of trilobites. He is currently an Assistant Statistician for the Scottish Government while continuing research as an honorary researcher at University College London. His primary research focuses on studying macroevolutionary patterns of body-size and diversity throughout the geological record. Currently, he contributes a regular column in the Palaeontological Association Newsletter called 'R for palaeontologists', aimed at teaching the basics of statistical programming with an emphasis on palaeontological techniques.

Davide Foffa. School of GeoSciences, The King’s Buildings, University of Edinburgh, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3FE. davidefoffa@gmail.com

Davide Foffa. School of GeoSciences, The King’s Buildings, University of Edinburgh, James Hutton Road, Edinburgh, EH9 3FE. davidefoffa@gmail.com

Davide Foffa completed his BSc in Geosciences at the University of Pisa (Italy) and his MSc in Palaeobiology at the University of Bristol (UK). He is currently a Ph.D. candidate under the supervision of Dr. Stephen L. Brusatte, Dr. Mark T. Young, Dr. Kyle G. Dexter. His research interests are the taxonomy, ecology and biomechanics of Mesozoic marine reptiles, but also late Triassic microvertebrate faunas. His PhD project focuses on macroevolution, niche partitioning and form-function of synchronous ichthyosaurs, plesiosaurs and thalattosuchians from the Middle-Late Jurassic formations of UK.

Lorna Steel. Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. l.steel@nhm.ac.uk

Lorna Steel. Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum, Cromwell Road, London, SW7 5BD, United Kingdom. l.steel@nhm.ac.uk

Lorna Steel obtained her MSc in Vertebrate Palaeontology at University College London (UK) and her PhD at University of Portsmouth (UK). She is currently Senior Curator in the Fossil Reptiles Section of the Department of Earth Sciences, Natural History Museum. She has collection management responsibility for the fossil bird, crocodylomorph and pterosaur collections, and has a research background in these taxa and in bone palaeohistology. She also undertakes field-based studies of cave systems and their bone-bearing deposits.

Sven Sachs. (1) Naturkundemuseum Bielefeld, Abteilung Geowissenschaften, Adenauerplatz 2, 33602 Bielefeld, Germany. (2) Im Hof 9, 51766 Engelskirchen, Germany. sachs.pal@gmail.com

Sven Sachs. (1) Naturkundemuseum Bielefeld, Abteilung Geowissenschaften, Adenauerplatz 2, 33602 Bielefeld, Germany. (2) Im Hof 9, 51766 Engelskirchen, Germany. sachs.pal@gmail.com

Sven is an associate researcher at the Naturkundemuseum in Bielefeld, Germany. His research focuses on the anatomy and evolution of plesiosaurs and other marine reptiles of the Mesozoic.

Current projects include reassessments of plesiosaur specimens from the Lower and Middle Jurassic of Germany and Luxembourg, elasmosaurid plesiosaurs from the Western Interior Seaway (Late Cretaceous) of North America and pliosauromorph plesiosaurs from the Late Cretaceous of the USA and Germany. Furthermore Sven is involved in a study on the plesiosaurian diversity and palaeoeology in the German Wealden. He lives in Engelskirchen near Cologne, Germany.

Karin Peyer. Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 8 rue Buffon, CP 38, F-75005, France. karin_peyer@yahoo.fr

Karin Peyer. Département Histoire de la Terre, Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle, Paris, 8 rue Buffon, CP 38, F-75005, France. karin_peyer@yahoo.fr

Karin Peyer is a researcher at the Muséum National d'Histoire Naturelle in Paris and Scientific Research Advisor to the "Galerie de Paléontologie et d'Anatomie comparée" at the MNHN in Paris.

She obtained her MSc at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill (US) and received her PhD from the MNHN in Paris (F). Her research interests include Late Triassic archosaurs, Middle-Late Jurassic theropod dinosaurs and thalattosuchians from Southern France (F), anatomy and functional morphology.

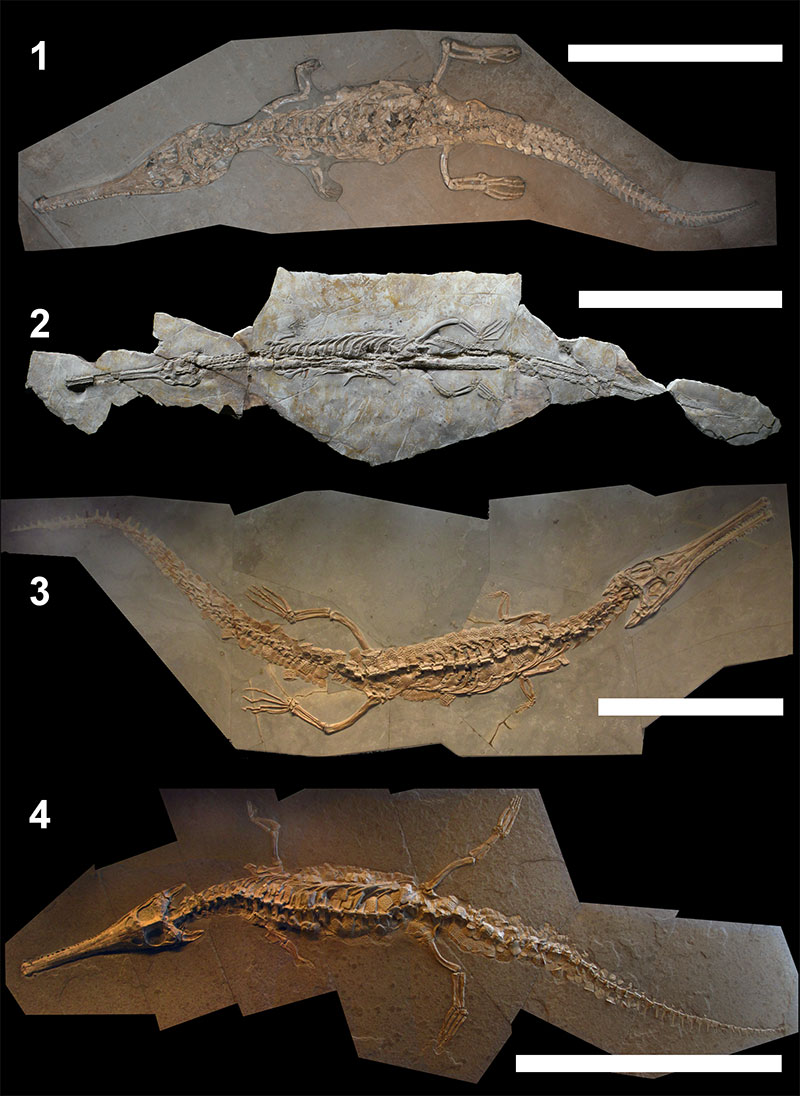

FIGURE 1. Comparative view of four fossil teleosaurid crocodylomorphs used in the regression analyses: (1) Steneosaurus bollensis GPIT/RE/1193/2; (2) Steneosaurus priscus MNHN.F CNJ 78a; (3) Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered A; and (4) Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered B. Scale bars equal 100 cm.

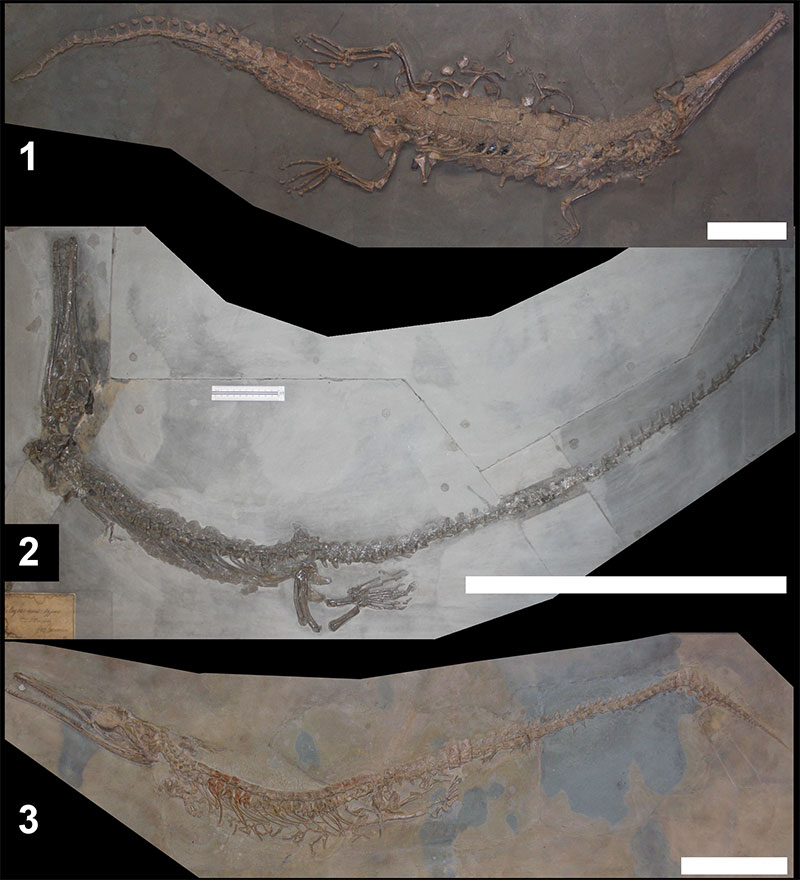

FIGURE 2. Comparative view of three fossil thalattosuchian crocodylomorphs: (1) teleosaurid Platysuchus multiscrobiculatus SMNS 9930; (2) basal metriorhynchoid Pelagosaurus typus MTM M62 2516; and (3) metriorhynchid Cricosaurus suevicus SMNS 9808. Scale bars equal 50 cm.

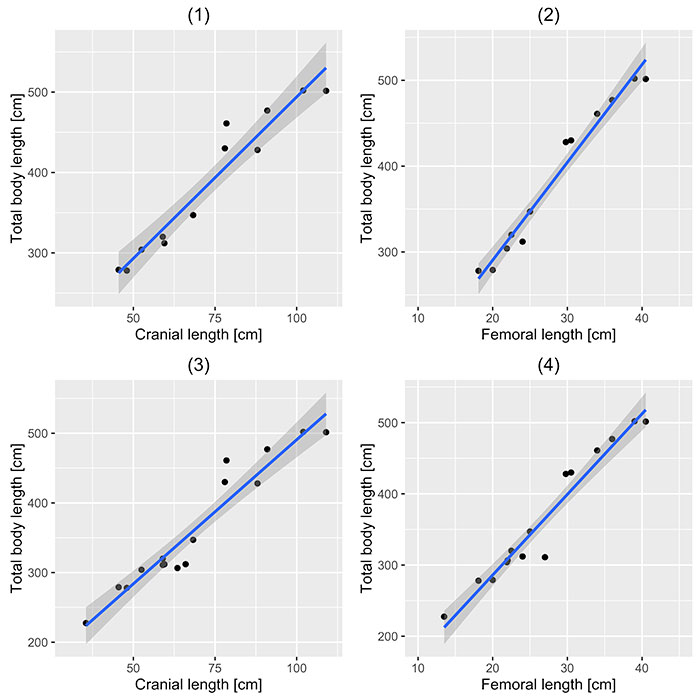

FIGURE 3. Bivariate plots of cranial (1, 3) and femoral lengths (2, 4) plotted against total lengths for complete specimens only (1, 2) and for all specimens (3, 4). In each case a line of least-squares regression is fitted along with a shaded area representing the confidence interval around the regression model.

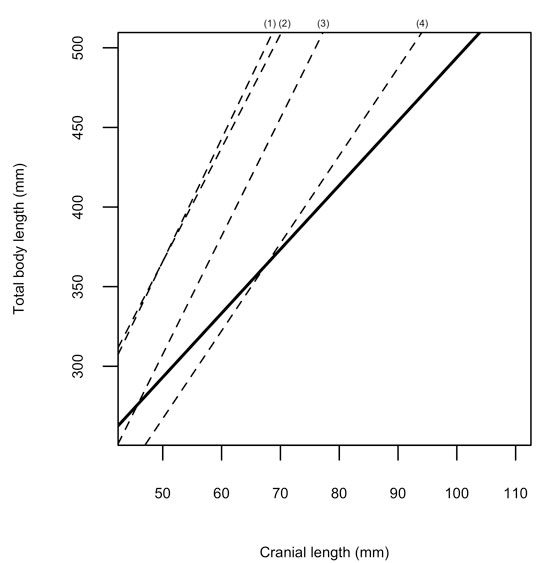

FIGURE 4. Comparative least-squares regression gradient plot, of cranial length-to-total length, with the solid line representing Teleosauridae, and the dashed lines representing (1) Crocodylus, (2) Alligator, (3) Gavialis, and (4) Metriorhynchidae, respectively.

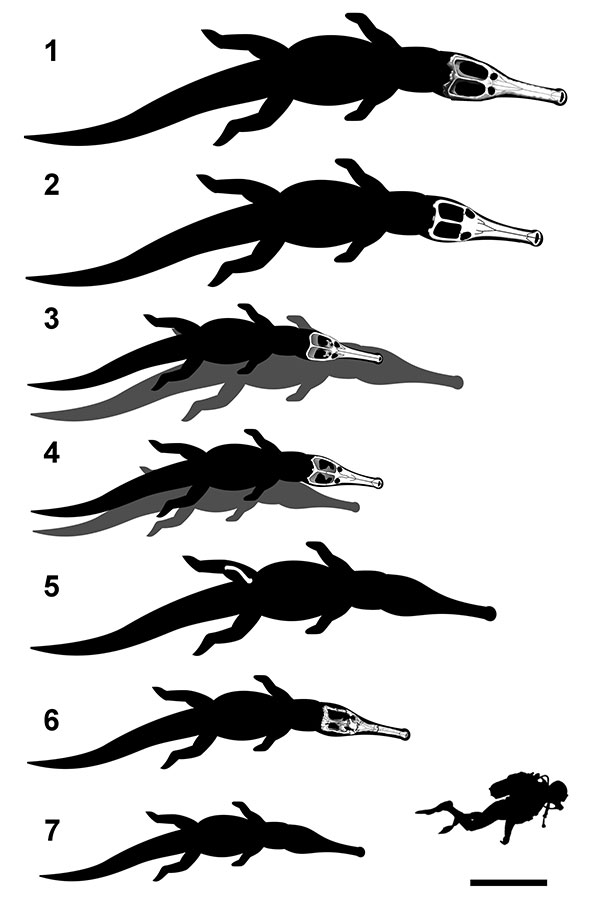

FIGURE 5. Comparative view of estimated body length of large-bodied teleosaurids (see Table 8). (1) Machimosaurus rex (holotype); (2) Machimosaurus hugii (referred specimen from Krebs, 1968); (3) Machimosaurus mosae (neotype, grey silhouette is the lost holotype); (4) Machimosaurus buffetauti (holotype, grey silhouette is the specimen from Buffetaut, 1982b); (5) Steneosaurus edwardsi (referred specimen from Johnson et al., 2015); (6) Steneosaurus obtusidens (holotype); (7) Steneosaurus bollensis (based on MH unnumbered A). The skull drawings are modified from (Fanti et al., 2016 and Young et al., 2014). Scale bar equals 1 m.

TABLE 1. Measurements of the teleosaurid specimens used in the first set of regression analyses (i.e. the most complete skeletons). All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Femoral length | Cranial length | Total body length |

| Platysuchus multiscrobiculatus SMNS 9930 |

20 | 45.5 | 279 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis GPIT/RE/1193/2 |

34 | 78.5 | 461 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered A |

36 | 91 | 477 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered B |

24 | 59.5 | 312 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 54063 |

30.5 | 78 | 430 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 52475 |

21.9 | 52.5 | 304 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 51984 |

22.5 | 59 | 320 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MTM unnumbered |

18.1 | 48 | 278 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi GPIT/RE/07286 |

39 | 102 | 502 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi PETMG R175 |

40.5 | 109 | 501.5 |

| Steneosaurus leedsi NHMUK PV R 3806 |

29.8 | 88 | 428 |

| Steneosaurus priscus MNHN.F CNJ 78a |

25 | 68.3 | 347 |

TABLE 2. Measurements of the teleosaurid specimens added to the second set of regression analyses (i.e., the skeletons lacking at least 10-20 cm of the distal tail). All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Femoral length | Cranial length | Total body length |

| Steneosaurus sp. SMNS 51753 |

24 | 66 | 312 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 51555 |

22 | 63.5 | 306.5 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 51957 |

27 | 59 | 311 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS uncatalogued |

13.5 | 35.5 | 227.5 |

TABLE 3. Measurements of the Pelagosaurus typus specimens. All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Femoral length | Cranial length | Total body length |

| SMNS 51753 | 17.5 | 42 | 233.5 |

| MTM M62 2516 | 11.1 | 27.5 | 145 |

TABLE 4. The 12 most complete teleosaurid specimens used in the regression analyses, with their recorded lengths and estimated lengths using the cranial-total body length equations of three extant species ( Alligator mississippiensis, Crocodylus porosus, and Gavialis gangeticus ). All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Measured length | Crocodylus equation | Gavialis equation | Alligator equation |

| Platysuchus multiscrobiculatus SMNS 9930 |

279 | 331.3 | 274.2 | 333.8 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis GPIT/RE/1193/2 |

461 | 585.2 | 518.9 | 568.9 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered A |

477 | 681.4 | 611.6 | 658.0 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered B |

312 | 439.0 | 378.0 | 433.5 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 54063 |

430 | 581.4 | 515.2 | 565.4 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 52475 |

304 | 385.1 | 326.1 | 383.6 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 51984 |

320 | 435.1 | 374.3 | 423.0 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MTM unnumbered |

278 | 350.5 | 292.8 | 351.6 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi GPIT/RE/07286 |

502 | 766.1 | 693.2 | 736.4 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi PETMG R175 |

501.5 | 820.0 | 745.1 | 786.3 |

| Steneosaurus leedsi NHMUK PV R 3806 |

428 | 658.3 | 589.4 | 636.7 |

| Steneosaurus priscus MNHN.F CNJ 78a |

347 | 506.7 | 443.3 | 496.2 |

TABLE 5. Estimated body lengths for the 12 most complete teleosaurid specimens used in the regression analyses. All four regression equations generated herein are compared against specimen recorded total lengths. All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Total body length (cm) | Total body length estimates (cm) | |||

| CL complete | CL incomplete | FL complete | FL incomplete | ||

| Platysuchus multiscrobiculatus SMNS 9930 |

279 | 275.05 | 265.20 | 290.46 | 285.95 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis GPIT/RE/1193/2 |

461 | 407.57 | 401.78 | 450.067 | 444.43 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered A |

477 | 457.77 | 453.52 | 472.86 | 467.07 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MH unnumbered B |

312 | 331.27 | 323.14 | 336.06 | 331.23 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 54063 |

430 | 405.57 | 399.71 | 410.16 | 404.81 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 52475 |

304 | 303.16 | 294.17 | 312.12 | 307.46 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis SMNS 51984 |

320 | 329.26 | 321.07 | 318.96 | 314.25 |

| Steneosaurus bollensis MTM unnumbered |

278 | 285.09 | 275.54 | 268.80 | 264.44 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi GPIT/RE/07286 |

502 | 501.95 | 499.05 | 507.06 | 501.03 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi PETMG R175 |

501.5 | 530.06 | 528.02 | 524.16 | 518.01 |

| Steneosaurus leedsi NHMUK PV R 3806 |

428 | 445.73 | 441.10 | 402.18 | 396.89 |

| Steneosaurus priscus MNHN.F CNJ 78a |

347 | 366.61 | 359.56 | 347.46 | 342.55 |

TABLE 6. Statistics for the results of the regression analyses comparing the fit of both the cranial and femoral lengths with the total body length, conducted individually for complete specimens only and for all specimens. The best fitting model is highlighted in bold.

| Dataset | Model | Multiple R2 |

Adjusted R2 |

p value | AIC | AICc | AICc weight |

| Complete specimens | Total length ~ Cranial length | 0.9315 | 0.9247 | <0.0001 | 114.3449 | 115.6783 | 0.0075 |

| Total length ~ Femoral length | 0.9696 | 0.9666 | <0.0001 | 104.5866 | 105.92 | 0.9925 | |

| All specimens | Total length ~ Cranial length | 0.9236 | 0.9182 | <0.0001 | 152.9013 | 153.8244 | 0.0603 |

| Total length ~ Femoral length | 0.9548 | 0.9478 | <0.0001 | 146.5062 | 148.5062 | 0.9397 |

TABLE 7. Estimated body lengths for the two Pelagosaurus typus specimens measured herein. All six thalattosuchian regression equations are compared against specimen recorded total lengths. All measurements in cm.

| Specimen | Total body length | 12 complete teleosaurids | All 16 teleosaurids | Metriorhynchids | |||

| CL | FL | CL | FL | CL | FL | ||

| SMNS 51753 | 233.5 | 256.97 | 261.96 | 246.57 | 257.65 | 217.58 | 247.94 |

| MTM M62 2516 | 145 | 202.76 | 189.00 | 190.69 | 185.20 | 143.25 | 166.71 |

TABLE 8. Estimated body lengths for large-bodied brevirostrine/mesorostrine teleosaurids, namely species in the genus Machimosaurus, and Steneosaurus edwardsi and S. obtusidens. All measurements in cm. Measurements in bold are estimates and/or based on reconstructed elements.

| Species | Cranial or femoral length | Total body length estimate | |

| Complete skeletons | Including incomplete tails | ||

| Machimosaurus rex (holotype) | 155 (CL; Fanti et al., 2016) | 714.80 | 718.42 |

| Machimosaurus hugii | 149 (CL; Krebs, 1968) | 690.70 | 693.58 |

| Machimosaurus mosae(holotype) | 130 (CL; Sauvage and Liénard, 1879) | 614.40 | 614.94 |

| Machimosaurus mosae (neotype) | 96.5 (CL; Hua, 1999) | 479.86 | 476.28 |

| Machimosaurus buffetauti | 100 (CL; Buffetaut, 1982b) | 493.92 | 490.77 |

| Machimosaurus buffetauti(holotype) | 93.5 (CL; Young et al., 2014) | 467.81 | 463.87 |

| Steneosaurus edwardsi | 53 (FL; Johnson et al., 2015) | 666.66 | 659.51 |

| Steneosaurus obtusidens (holotype) | 116 (CL; Andrews, 1913) | 558.17 | 556.00 |

Big-headed marine crocodyliforms and why we must be cautious when using extant species as body length proxies for long extinct relatives

Plain Language Abstract

Teleosaurids were the largest fossil crocodylomorphs (extinct relatives of modern crocodiles) of the Jurassic and early-part of the Early Cretaceous. Due to their long tubular snouts, high tooth counts and large jaw muscle attachment sites, they have long been considered to be 'marine gavials' (as these groups share these characteristics). However, the largest known teleosaurid species have been estimated to reach body lengths of 9–10 m. Unfortunately, these estimates are based on incomplete specimens. More problematic is the lack of body length regression equations for teleosaurids, meaning there is currently no reliable method for estimating their body lengths.

The aim of this paper is two-fold: firstly to provide a reliable method for estimating the body length of incomplete teleosaurid specimens and secondly to test whether teleosaurids are indeed 'marine gavials'. These were accomplished by taking measurements from 16 teleosaurid skeletons, and using least-squares linear regression analyses to generate equations of skull length against total body length, and femoral length against total body length.

Our results were intriguing. Based on our regression equations, and using maximum likelihood modelling, we show that femoral length is a more reliable proxy for estimating total body length than using skull length. Furthermore, our equations dramatically reduce the estimated body lengths of the 9–10 m long giant teleosaurids to 6.9–7.15 m. Finally, the ‘marine gavial’ characterisation is rejected, as teleosaurids had proportionally larger skulls relative to body length than other crocodylomorphs, and using the gavial skull length against total body length regression equation yields large over-estimates for teleosaurids.

Resumen en Español

Crocodiliformes marinos de cabeza grande y por qué hay que tener precaución al usar especies actuales como correlatos respecto a la estimación de la longitud corporal de grandes parientes extintos

El tamaño del cuerpo se utiliza comúnmente como una variable clave para la estimación de las tendencias ecomorfológicas a una escala macroevolutiva, proporcionando estimaciones fiables de la longitud del cuerpo de taxones fósiles de importancia crítica. Los cocodrilomorfos (crocodilios actuales y sus parientes extintos) desarrollaron numerosos planes corporales "aberrantes" durante su historia evolutiva de alrededor de 230 millones de años, las cuales variaban desde las especies terrestres semejantes a ungulados hasta especies pelágicas que recuerdan a delfines. Tales clados desarrollaron distintas relaciones de escala craneales y femorales (en comparación con la longitud total del cuerpo), con lo que los taxones existentes no son correlatos adecuados para la estimación de sus longitudes corporales. Aquí mostramos que el clado fósil Teleosauridae también encaja en esta categoría. Los Teleosauridae eran un clado predominantemente marino de aguas someras que tenía una distribución cosmopolita durante el Jurásico. Sabido que desarrollaron una amplia gama de longitudes corporales (2-5 m calculado a partir de esqueletos completos), actualmente no hay modo de estimar de forma fiable el tamaño de los ejemplares incompletos. Esto es sorprendente, ya que se ha considerado que algunos Teleosauridae eran muy grandes (9-10 m de longitud total), con lo que de acuerdo con ello los Teleosauridae serían el clado con cuerpos más voluminosos durante los primeros 100 millones de años de la evolución de los cocodrilomorfos. Nuestro examen y los análisis de regresión de los esqueletos mejor conservados de Teleosauridae demuestran que: eran más pequeños de lo que se pensaba, de forma que no se conocen ejemplares que excedan los 7,2 metros de longitud, y que tenían proporcionalmente grandes cráneos, y proporcionalmente fémures cortos, en comparación con la longitud del cuerpo. Por lo tanto, mientras que muchas especies de Teleosauridae desarrollaron una longitud craneal de ≥1 m, estos taxones no necesariamente fueron mayores que las especies vivas en la actualidad. Se aconseja que al estimar la longitud del cuerpo de taxones extintos se sea cauto, especialmente para los que están fuera del grupo corona.

Palabras clave: longitud corporal; Mesozoico; Metriorhynchidae; Evolución fenotípica; Teleosauridae

Traducción: Enrique Peñalver (Sociedad Española de Paleontología)

Résumé en Français

Des crododyliformes marins à grosses têtes et pourquoi nous devons être prudents quand nous utilisons les espèces actuelles comme indicateurs de la longueur corporelle d'espèces apparentées éteintes depuis longtemps

La taille corporelle est fréquemment utilisée comme une variable clé pour estimer les tendances écomorphologiques à une échelle macro-évolutive, ce qui rend cruciales les estimations de longueur corporelle des taxons fossiles. Les crocodylomorphes (crocodiliens actuels et les espèces apparentées éteintes) ont évolué de nombreux plans corporels « aberrants » pendant leur histoire évolutive d'environ 230 millions d'années, allant des espèces terrestres à « sabots » aux espèces pélagiques convergentes avec les dauphins. Ces clades ont évolué des proportions de la tête et du fémur distinctes (par rapport à la longueur totale du corps), faisant ainsi des taxons actuels des indicateurs inappropriés pour estimer leurs longueurs corporelles. Nous illustrons ici que cela est également le cas pour le clade fossile Teleosauridae. Les téléosauridés étaient un clade d'espèces habitant principalement les mers peu profondes, avec une distribution globale pendant le Jurassique. Ils sont connus pour avoir évolué une gamme variée de longueurs corporelles (de 2 à 5 mètres d'après les squelettes complets), mais il n'y a pas actuellement de méthode pour estimer de manière fiable la taille des spécimens incomplets. Cela est surprenant car certains téléosauridés ont été considérés comme étant très grands (de 9 à 10 mètres en longueur totale), faisant de cette famille le clade à la taille corporelle la plus grande pendant les premiers 100 millions d'années de l'évolution des crocodylomorphes. Notre étude et analyses de régression des squelettes de téléosauridés les mieux préservés démontrent que : ils étaient plus petits que l'on pensait, avec aucun spécimen ne dépassant 7,2 m de longueur ; et ils avaient des têtes grosses, et des fémurs courts, proportionnellement à leur longueur corporelle. Ainsi, bien que de nombreuses espèces de téléosauridés aient évolué une longueur crânienne dépassant un mètre, ces taxons n'étaient pas nécessairement plus gros que les espèces actuelles. Nous appelons à la prudence quand il s'agit d'estimer la longueur corporelle de taxons éteints, en particulier pour ceux en dehors du groupe-couronne.

Mots-clés : longueur corporelle ; Mésozoïque ; Metriorhynchidae ; évolution phénotypique ; Teleosauridae

Translator: Antoine Souron

Deutsche Zusammenfassung

Großköpfige marine Crocodyliforme und warum wir vorsichtig sein müssen wenn rezente Arten als Grundlage zur Errechnung der Körperlänge ausgestorbener Verwandter herangezogen werden

Körpergröße dient oft als Schlüsselvariable für die Bewertung von ökomorphologischen Trends im makroevolutionären Maßstab. Die zuverlässige Schätzung von Körperlängen fossiler Taxa ist daher besonders wichtig. Crocodylomorphe (rezente Krokodile und ihre ausgestorbenen Verwandten) entwickelten im Laufe ihrer etwa 230 Millionen Jahre währenden Geschichte zahlreiche 'aberrante' Körpermodelle, die von 'hufetragenden' terrestrischen Formen bis zu delfinartigen pelagischen Spezies reichen. Solche Kladen entwickelten ebenfalls ausgeprägte craniale und femorale Skalierungsverhältnisse (verglichen zur kompletten Körperlänge), weshalb ihre Gesamtlängen nicht durch Vergleiche mit rezenten Taxa errechnet werden können. Hier zeigen wir dass dies ebenfalls für die fossile Klade der Teleosauridae gilt. Teleosauriden waren eine überwiegend flachmarine Klade, die während des Jura eine globale Verbreitung besaß. Obwohl bekannt ist dass ihre Körperlängen variierten (2–5 m basierend auf vollständigen Skeletten) gibt es bisher keine Möglichkeit die Größe von unvollständigen Exemplaren zuverlässig zu errechnen. Dies ist überraschend da für einige Teleosauriden Längen von 9–10 m erwogen wurden was die Teleosauridae zu der größten Klade während der ersten 100 Millionen Jahre der Evolution der Crocodylomorphen machen würde. Unsere Untersuchungen und Regressionsanalysen der am besten erhaltenen Skelette von Teleosauriden zeigt, dass: sie kleiner waren als zuvor vermutet, wobei kein bekanntes Exemplar eine Länge von 7.2 m überschritt und dass sie proportional große Schädel und proportional kurze Femora besaßen (jeweils im Verhältnis zur Gesamtlänge). Da viele Teleosauriden eine Schädellänge von ≥1 m hatten waren diesen Taxa somit nicht unbedingt größer als heute lebende Arten. Wir raten daher zur Vorsicht bei der Bewertung der Körperlänge von ausgestorbenen Taxa, speziell für solche außerhalb der Kronengruppe.

Schlüsselwörter: Körperlänge; Mesozoikum; Metriorhynchidae; phänotypische Evolution; Teleosauridae

Translator: Authors

Italiano

Crocodiliformi marini dalle grandi teste e le ragioni per cui si deve essere cauti nell'usare specie odierne come metri di paragone per studio delle dimensioni di parenti estinti

Le dimensioni di un organismo è uno dei fattori comunemente usati nello studio dei trend morfologici ed ecologici a livello macroevolutivo. Ciò rende fondamentali le stime di lunghezza totale di taxa fossili. Nel corso dei circa 230 milioni di anni della loro storia, tra i crocodilomorfi (coccodrilli moderni e i loro parenti estinti) si sono evolute numerose volte delle forme 'aberranti' con caratteristici piani corporei: da specie terrestri e cursorie fino a specie pelagiche paragonate a delfini. Questi cladi sono caratterizzati da distinte proporzioni di cranio e femore rispetto alla lunghezza totale del corpo; una circostanza che rende i loro parenti moderni inadatti per stimarne le dimensioni totali. Qui dimostriamo che il clade Teleosauridae fa parte di quest'ultima categoria. I teleosauridi erano un gruppo che abitava prevalentemente bassi ambienti marini e che ebbe una distribuzione globale durante il Giurassico. È risaputo che questi animali occupavano un ampio spettro di misure (si stima da 2 a 5 metri di lunghezza totale basandosi su scheletri completi), tuttavia ancora non ci sono metodi affidabili per determinare le dimensioni di esemplari incompleti. Tutto questo è sorprendente, in particolar modo alla luce della supposizione che alcuni teleosauridi raggiunsero grandi dimensioni (9–10 metri in lunghezza totale). Questo rende Teleosauridae il clade i cui rappresentati raggiunsero le maggiori dimensioni durante i primi 100 milioni di anni di evoluzione dei crocodilomorfi. La nostra analisi di regressione ed esame degli scheletri dei teleosauridi meglio conservati dimostra che questi animali avevano dimensioni più ridotte di quanto si credesse, con nessun esemplare conosciuto lungo più di 7.2 m e che, in proporzione, rispetto alle dimensioni totali, avevano crani grandi e femori corti. Dunque, si più concludere, che nonostante molte specie di teleosauridi evolvettero crani di lunghezza superiore al metro, questi taxa non erano necessariamente più grandi dei coccodrilli odierni. Di conseguenza, raccomandiamo cautela nello stimare le dimensioni di taxa estinti, specialmente quelli al di fuori del crown group.

Parole chiave: Lunghezza totale; Mesozoico; Metriorhynchidae; evoluzione del fenotipo; Teleosauridae.

Translator: Authors

Arabic

Translator: Ashraf M.T. Elewa

-

-

PE: An influential journal

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journals

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journalsArticle number: 27.2.2E

July 2024

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei