Volume 28.2

May–August 2025

Full table of contents

ISSN: 1094-8074, web version;

1935-3952, print version

Recent Research Articles

See all articles in 28.2 May-August 2025

See all articles in 28.1 January-April 2025

See all articles in 27.3 September-December 2024

See all articles in 27.2 May-August 2024

Interested in submitting a paper to Palaeontologia Electronica?

Click here to register and submit.

Article Search

Kai R.K. Jäger. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. jaegerk@uni-bonn.de

Kai R.K. Jäger. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. jaegerk@uni-bonn.de

Kai Jäger gained his Diploma in Geology and Paleontology in 2013 at the University of Bonn. His diploma thesis was based on the postcranial skeleton of the Jurassic mammal Henkelotherium guimarotae. He is currently a Ph.D. student at Professor Thomas Martin’s lab at the Steinmann Institute. His research interest include Mesozoic mammals, functional morphology of dentitions, as well as mammalian locomotion. Micro-computed tomography (CT) and other techniques for digital visualization and analysis of fossils such as reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) are frequently used methods in most of his projects. Since 2010, he is the student representative and since 2012 a representative for Marketing and PR for the Paläontologische Gesellschaft. Science outreach is of special interest to Kai Jäger. He participates in science slams and won the German science slam championship in 2014.

Helmut Tischlinger. Tannenweg 16, 85134 Stammham, Germany. htischlinger@t-online.de

Helmut Tischlinger. Tannenweg 16, 85134 Stammham, Germany. htischlinger@t-online.de

Helmut Tischlinger worked as a teacher near Ingolstadt, Germany, until his retirement in 2006. He has been a voluntary staff member at the Jura-Museum in Eichstätt, Germany, since 1970. His scientific work is dedicated to the Upper Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone. During the past 15 years he focused on the investigation of soft parts by ultraviolet light using filtering techniques of his own design. Dinosaurs including Archaeopteryx, pterosauria, Lepidosauria and various invertebrates from Solnhofen-type lagerstaetten are the main topic of his research. His other research interests include Jurassic and Cretaceous pterosaurs and feathered dinosaurs from China. He received an honorary PhD degree from the University of Munich in 2007 and the Zittel Medal of the Paläontologische Gesellschaft in 2013.

Georg Oleschinski. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. g.oleschinski@uni-bonn.de

Georg Oleschinski. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. g.oleschinski@uni-bonn.de

Georg Oleschinski is a professional photographer at the Steinmann Institute of the University of Bonn. In 1982, he finished his education as a photographer at the sudio Wim Cox in cologne. He became a photographer for the University of Bonn in 1983 and has since then contributed to numerous scientific publications and illustrations. Over the last 30 years, he featured in several art exhibitions. Georg Oleschinski is skilled in both print and digital photography. His personal emphasis is a patient, thoughtful approach to photography.

P. Martin Sander. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. martin.sander@uni-bonn.de

P. Martin Sander. Division of Paleontology, Steinmann Institute for Geology, Mineralogy, and Paleontology, University of Bonn, Nussallee 8, 53115 Bonn, Germany. martin.sander@uni-bonn.de

P. Martin Sander is professor of vertebrate paleontology at the Steinmann Institute of the University of Bonn and previously had been the curator of its Goldfuß Museum for over 10 years. After his undergraduate work at the University of Freiburg in Germany, Dr. Sander obtained a Master's degree at the University of Texas at Austin in 1984 and a Ph.D. from the University of Zurich, Switzerland, in 1989. Since then, he has divided his research interests between the more traditional work in paleontology such as excavating and studying Triassic marine reptiles around the globe, and a more biological approach to extinct vertebrates, using the microstructure of fossil bone as a clue to life history and evolution. A spectacular application was the proof that dinosaurs were subject to island dwarfing. In 2004, Dr. Sander was able to obtain major funding from the German Research Foundation (DFG) for the study of dinosaur biology and headed DFG Research Unit 533 "Biology of the Sauropod Dinosaurs: The Evolution of Gigantism” until 2014. Since 1987, Dr. Sander has authored numerous scientifc papers and books on his research, and since 1995 has trained many graduate students at the University of Bonn.

FIGURE 1. Photograph of the main slab of the holotype specimen of the non-pterodactyloid pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris (Goldfuß, 1831) catalogued as SIPB Goldfuß 1304a from the Late Jurassic Solnhofen Lithographic Limestone of Bavaria. The skeleton is seen in right lateral view with the skull, neck, trunk, and much of the limbs preserved. The skull was prepared from both sides by Georg August Goldfuß himself (Goldfuß, 1831). Preserved soft parts are not immediately obvious in this photograph.

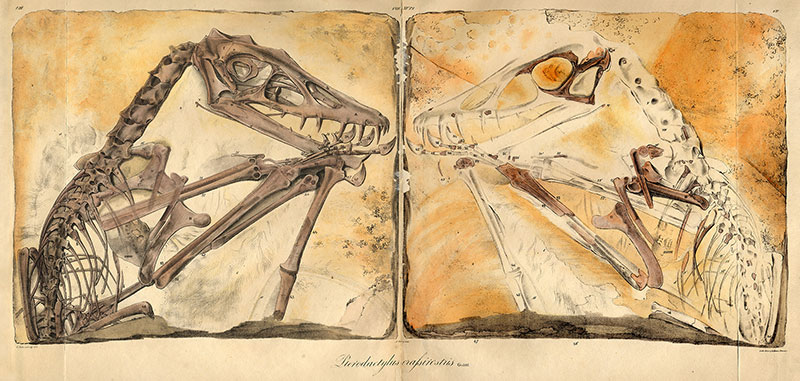

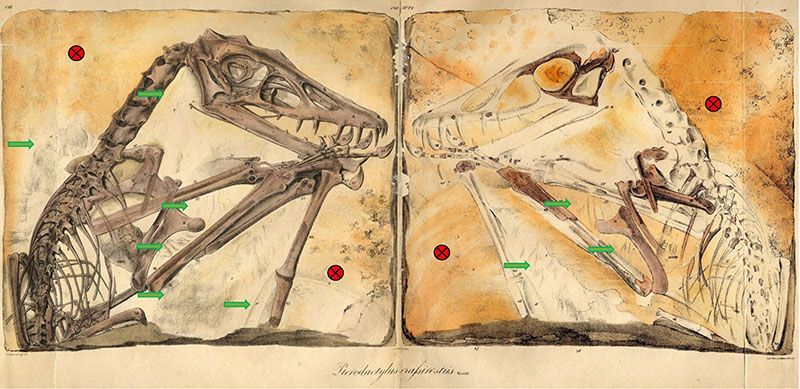

FIGURE 2. Hand-colored lithographic plates drawn by Nicolaus Christian Hohe from Goldfuß (1831) showing main slab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304a: Goldfuß, 1831, plate 8) and counterslab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304b: Goldfuß, 1831, plate 7) of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus crassirostris. Note the high accuracy of the images but the artistic license. This consists of depicting the slab as a rectangular plate, although the actual specimen (see Figure 1) is missing the upper right corner because Goldfuß prepared the skull from both sides. In the lithographs, Goldfuß had the soft part preservation depicted and labelled (see also Figure 10).

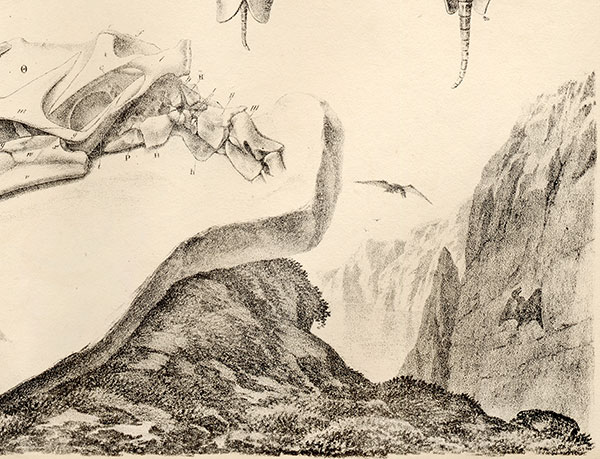

FIGURE 3. Scaphognathus crassirostris life reconstruction. This illustration was published by Goldfuß (1831) as a vignette in the lower right corner of a larger plate (tab. IX) that contains drawings of the skeletal reconstructions of Scaphognathus crassirostris. This vignette is the first life reconstruction of an extinct vertebrate in its environment in a scientific publication (Rudwick, 1992).

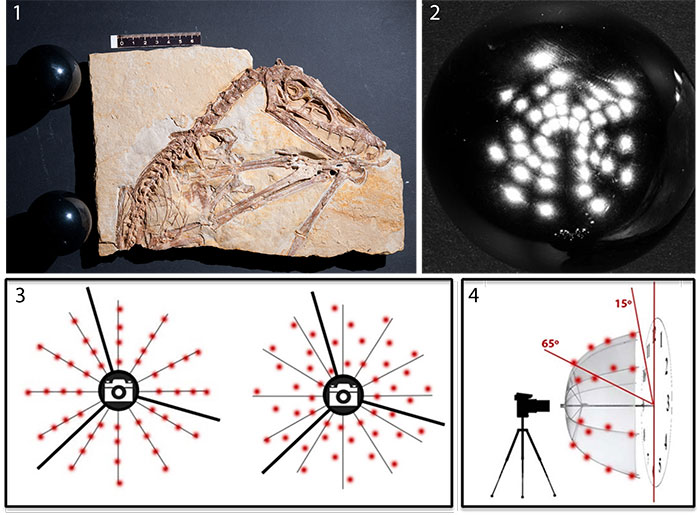

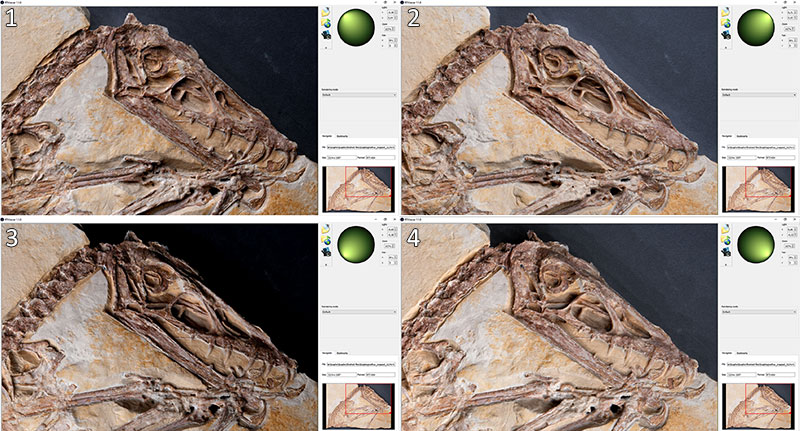

FIGURE 4. Photography setup for the mobile highlight technique of image capture for RTI/PTM imaging. 1, A single source photograph from the capturing process. The light source (flash) is positioned on the upper right side as seen on the reflectance of the black reference spheres. 2, A composite image of all flash positions is generated by the RTIBuilder software to check if spaces were missed during the capturing process. The elongate gap at the bottom is caused by one of the legs of the tripod. 3, The setup in top view. The camera is positioned above or in front of the target. The flash is moved along a contour of a virtual hemisphere at a distance of approximately three times the diameter of the object. The red dots symbolize the flash positions for the captured images. Left: Good distribution of flash positions that leaves no gaps and covers the whole object, recommended for inexperienced photographers. Right: Ideal distribution with equal distance between flash positions. 4, The setup in side view with the camera, the object, the virtual hemisphere, and flash positions. The flash positions should be at angles from at least 65° to 15° to the object. 3 and 4 are modified from Bogart (2013a).

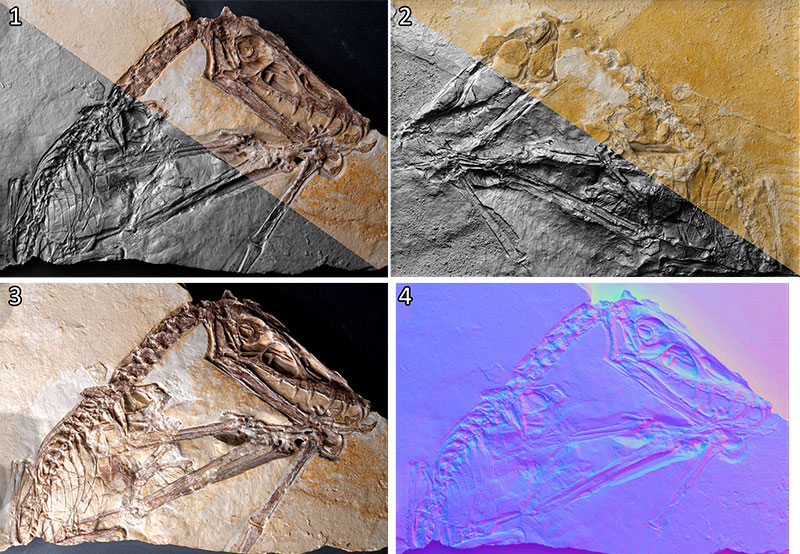

FIGURE 5. 1-4, Series of RTIViewer snapshots of the .rti file of the main slab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304a) of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus crassirostris with low-angle light from different directions in default rendering mode. Light positions (green sphere) and a navigation overview is visible on the right side of each image. The direction of the light source can be manipulated by clicking on the green sphere or by assigning specific coordinates to the light source position.

FIGURE 6. The main slab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304a) of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus crassirostris with snapshots of different rendering modes of the.rti file. Light is from the upper left. 1, Image of main slab showing default setting (upper right) and specular enhancement with erased color information, medium specularity and highlight size (lower left). 2, Image of counter slab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304b) showing default setting (upper right) and specular enhancement with erased color information, medium specularity and highlight size (lower left). 3, Main slab viewed with color information, enhanced specularity and low highlight size. 4, Main slab viewed in normals visualization mode.

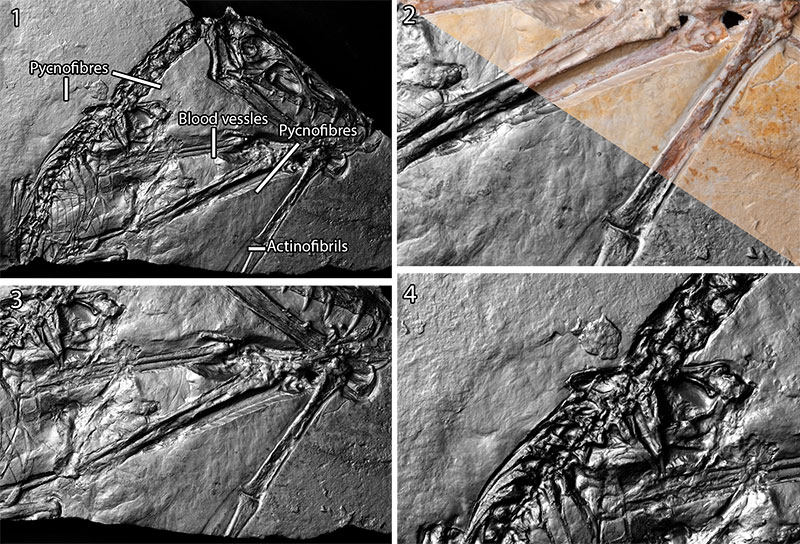

FIGURE 7. Close-ups of RTIViewer snapshots of the.rti file of the main slab (SIPB Goldfuß 1304 a) of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus crassirostris showing soft parts with different settings and light positions. Compare to Figure 9. 1, Soft tissue with specular enhancement rendering and low-angle light. 2, Comparison of the close-up of the right arm divided between default view and specular enhancement. Note that the pycnofibers and the region of the wing membrane with the aktinofibrils is much better visible with specular enhancement 3, Specular enhancement of the region of the wing skeleton. Impressions of blood vessels and pycnofibers are clearly visible, while the aktinofibrils next to the joint of the first and second phalanx are hardly visible. 4, Dorsal region with specular enhancement. Pycnofibers are much better visible compared to the UV light image (Figure 9.2).

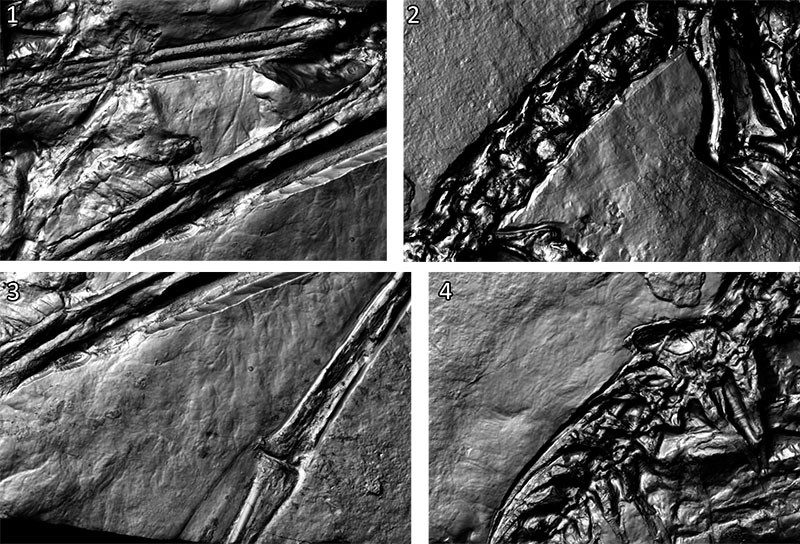

FIGURE 8. Magnification with RTIViewer enables zooming beyond the magnification of the photos by up to 200%. While this digital magnification is based on interpolation, rendering modes without color, like the specular enhancement mode, provide relatively sharp images beyond magnifications of 100% (Bogart, 2013b). 1, Blood vessels. 2, Pycnofibers ventral to the neck. 3, Aktinofibrils and displaced pycnofibers. 4, Dorsal pycnofibers.

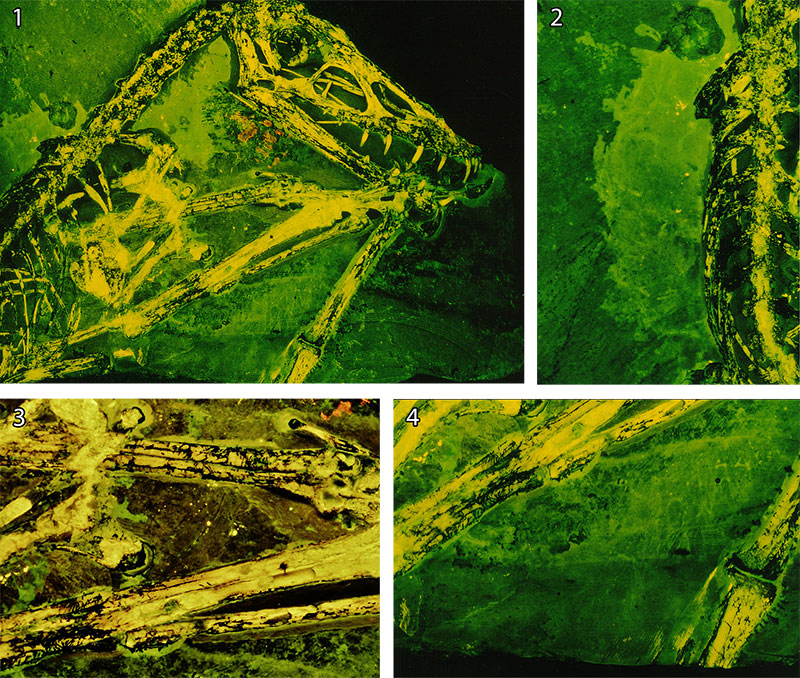

FIGURE 9. UV images of the main slab of Scaphognathus crassirostris SIPB Goldfuß 1304a modified from Tischlinger (2003). Bone apatite fluoresces yellow. 1, Main slab of holotype specimen. 2, Region of dorsal vertebral column on main slab. The light green hues suggest the presence of soft tissue. However, the impressions of the pycnofibers are not visible under UV light. 3, Wing membrane in the area enclosed by the left and right radius and ulna. Blood vessels are visible as dark lines. 4, Wing membrane aktinofibrils on the right wing finger next to the joint of the first and second phalanx. In the upper region of the wing membrane area, there are faintly visible displaced pycnofibers.

FIGURE 10. Comparison of soft tissue detection between this study and Goldfuß (1831, plates 7 and 8) on the main slab (left, SIPB Goldfuß 1304a) and counterslab (right, SIPB Goldfuß 1304b) of the holotype specimen of Scaphognathus crassirostris. Green arrows: Soft tissue depicted or described by Goldfuß and also detected by either RTI or UV light in this study. Red circles: No soft tissue detectable in this study.

The Supplementary Materials are available in a zipped file.

1. Translation of selected parts of Goldfuß (1831) by PMS.

2. RTI file of the main slab of Scaphognathus crassirostris (holotype). Viewable with RTIViewer (Corsini et al., 2002).

3. RTI file of the counter slab of Scaphognathus (holotype). Viewable with RTIViewer (Corsini et al., 2002).

Goldfuß was right: Soft part preservation in the Late Jurassic pterosaur Scaphognathus crassirostris revealed by reflectance transformation imaging (RTI) and UV light and the auspicious beginnings of paleo-art

Plain Language Abstract

Pterosaurs were flying reptiles that lived during the Mesozoic Era. Scaphognathus crassirostris, a small pterosaur from the Jurassic Solnhofen Limestone, was described by the German paleontologist Georg August Goldfuß in 1831. Goldfuß was the first to recognize that pterosaurs had some type of “fur”, based on fiber impressions in the limestone surrounding the specimen. Despite his detailed description and the first life reconstruction of an extinct animal in a scientific publication, his findings were rejected by the upcoming generation of paleontologists in the middle of the 19th century. Due to new well-preserved fossils, it became widely accepted that pterosaurs had “fur” in the 20th century. However, Goldfuß' findings were almost forgotten and received little attention from the scientific community. In 2003 Helmut Tischlinger confirmed Goldfuß by using ultraviolet light (UV light), which supported the presence of soft tissue in the places noted by Goldfuß. We applied an additional method, reflectance transformation imaging (RTI), in order to compare it to UV light and to illustrate the structures mentioned by Goldfuß. RTI is a method that uses multiple images of an object, all taken from the same position but with varying photoflash positions. The pictures are subsequently processed with the freeware software RTIBuilder to create a virtual image with a movable light source. Additional rendering modes enable the user to analyze the structure in detail. This method was originally developed by Malzbender et al. (2000, 2001) and called polynomial texture mapping (PTM). Nowadays PTM is one specific type of RTI. Since its development, RTI has frequently been used in archaeology, but is still almost unknown in paleontology, with only two paleontological papers published in the past 16 years (Hammer et al., 2003; Hammer and Spocova, 2013). This is quite surprising since RTI holds great potential for paleontological studies in having the ability to display minor relief differences. We were able to confirm Goldfuß' findings and to show the soft tissue in unique clarity. Compared to UV light, RTI lacks the ability to show the type of substance preservation based on the presence of certain compounds. RTI, on the other hand, provides better results in regions where the soft tissue is mostly preserved as imprints. We conclude that RTI holds great high potential for paleontological analyses since it is easy to apply and comes in handy when analyzing flat fossils on slabs of sediment. For studies on fossil soft tissue, we recommend the application of RTI as an addition to UV light.

Resumen en Español

Goldfuß tenía razón: preservación de partes blandas en el pterosaurio del Jurásico tardío Scaphognathus crassirostris revelada por imágenes por transformación de reflectancia (RTI) y luz UV y los auspiciosos comienzos del paleo-arte

La Imágenes por Transformación de Reflectancia (RTI) es una técnica basada en múltiples fotos digitales con una posición de cámara fija e iluminación desde diferentes direcciones. Estas fotos se procesan para crear un archivo de imagen en el que la posición de la fuente de luz y las propiedades de reflectancia se pueden modificar digitalmente. El método se usa con frecuencia en arqueología debido a sus capacidades para visualizar detalles de la superficie. Aquí aplicamos imágenes de RTI en el holotipo del pterosaurio no pterodactiloide Scaphognathus crassirostris de la famosa caliza litográfica de Solnhofen, del Jurásico tardío, y comparamos los resultados con imágenes de luz ultravioleta (UV). El espécimen es de particular interés histórico ya que fue el primer pterosaurio para el que el paleontólogo y geólogo alemán Georg August Goldfuß describió un integumento "similar a la piel" en 1831. Su publicación sobre este fósil incluye inferencias paleobiológicas detalladas y culmina con la publicación de la primera reconstrucción científica de cómo vivía en su entorno un vertebrado extinto. Sin embargo, la conservación de partes blandas no fue aceptada como un hecho real por científicos posteriores como Herman von Meyer, y el trabajo de Goldfuß sobre preservación de partes blandas, paleobiología y paleo-arte fue en gran parte olvidado. Con la técnica RTI y la luz UV, las picnofibras que cubrían el cuello y otras partes del cuerpo, así como actinofibrillas y vasos sanguíneos en la membrana del ala, se visualizaron en el espécimen de Scaphognathus crassirostris, confirmando en gran medida las observaciones de Goldfuß. La aplicación de la técnica RTI es técnicamente sencilla y es prometedora para realizar estudios paleontológicos, especialmente para fósiles planos en losas de roca sedimentaria, donde pequeñas diferencias en el relieve pueden suponer información crucial. Por lo que sabemos, este es el primer estudio que aplica RTI para investigar la conservación de partes blandas en fósiles de vertebrados.

Palabras clave: Scaphognathus crassirostris; Goldfuß; Jurásico; conservación de partes blandas; imágenes por transformación de reflectancia; luz ultravioleta

Traducción: Enrique Peñalver (Sociedad Española de Paleontología)

Résumé en Français

Goldfuß avait raison : la préservation des tissus mous du ptérosaure Scaphognathus crassirostris (Jurassique récent) révélée par imagerie par transformation de la réflectance (ITR) et lumière UV, et les débuts encourageants du paléo-art

L’Imagerie par Transformation de la Réflectance (ITR) est une technique basée sur de multiples photographies numériques prises avec une caméra en position fixe et une lumière provenant de directions différentes. Ces photographies sont traitées pour créer un fichier image dans lequel la position de la source de lumière et les propriétés de réflectance peuvent être modifiées numériquement. Cette méthode est fréquemment utilisée en archéologie pour sa capacité à visualiser les détails d’une surface. Dans cet article, nous appliquons l’ITR à l’holotype du ptérosaure non-ptérodactyloïde Scaphognathus crassirostris, provenant des célèbres calcaires lithographiques du Jurassique récent de Solnhofen et nous comparons les résultats avec ceux obtenus par imagerie par lumière ultra-violette (UV). Ce spécimen est d’un intérêt historique particulier car il est le premier ptérosaure pour lequel un tégument ressemblant à des poils a été décrit en 1831 par le paléontologue et zoologue allemand Gorg August Goldfuß. La publication de ce fossile par Goldfuß inclut des déductions paléobiologiques détaillées et aboutit à la première reconstruction scientifique publiée de l’apparence d’un vertébré éteint lorsqu’il était vivant dans son environnement. Cependant, la préservation des tissus mous n’a pas été acceptée par les scientifiques ultérieurs comme Herman von Meyer, et le travail de Goldfuß sur la préservation des tissus mous, la paléobiologie, et le paléo-art a été largement oublié. L’ITR et la lumière UV ont permis de visualiser les pycnofibres couvrant le cou et le corps ainsi que des actinofibrilles et des vaisseaux sanguins sur la membrane de l’aile du spécimen de Scaphognathus crassirostris, confirmant en grande partie les observations de Goldfuß. L’application de l’ITR est techniquement aisée et prometteuse pour les études paléontologiques, en particulier dans le cas des fossiles aplatis sur des plaques de sédiments, pour lesquels des différences mineures de relief peuvent révéler des informations cruciales. À notre connaissance, cette étude est la première à appliquer l’ITR à la préservation des tissus mous chez des fossiles de vertébrés.

Mots-clés : Scaphognathus crassirostris ; Goldfuß ; Jurassique ; préservation des tissus mous ; imagerie par transformation de la réflectance ; lumière ultra-violette

Translator: Antoine Souron

Deutsche Zusammenfassung

Goldfuß hatte recht: RTI und UV-Licht belegen Weichteilerhaltung beim oberjurassischen Pterosaurier Scaphognathus crassirostris und der vielversprechende Anfang der paläontologischen Lebendrekonstruktionen

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) ist eine Visualisierungsmethode, welche digitale Fotos mit fixer Kameraposition und unterschiedlicher Belichtungsrichtung verwendet. Diese werden verarbeitet und eine Bilddatei erzeugt, in der der Belichtungswinkel sowie die Reflektionseigenschaften des Objektes digital verändert werden können. In dieser Studie wurde der Holotyp des Nicht-Pterodaktylen Pterosauriers Scaphognathus crassirostris, aus den weltberühmten Solnhofener Plattenkalken, mittels RTI untersucht, und die Ergebnisse mit denen von bildgebenden Verfahren mit Ultraviolettem Licht (UV) verglichen. Das Stück ist von besonderem wissenschaftshistorischem Interesse, da es das sich hierbei um den ersten Pterosaurier handelt, für den bereits 1831 von dem deutschen Paläontologen Georg August Goldfuß das Vorhandensein von „Haaren“ beschrieben wurde. Seine Publikation enthält bereits detaillierte paläobiologische Hypothesen, sowie die erste wissenschaftliche Lebendrekonstruktion eines ausgestorbenen Wirbeltiers in seinem Lebensraum. Von der folgenden Generation von Wissenschaftlern, wie beispielsweise Herman von Meyer, wurde jedoch die Möglichkeit von Weichteilerhaltung abgelehnt, und so wurde Goldfuß Beitrag zur Weichteilerhaltung, Paläobiologie und Rekonstruktion weitestgehend vergessen. Mittels RTI und UV-Licht konnten Pycnofibrillen, Aktinofibrillen und Blutgefäße auf der Flughaut von Scaphognathus crassirostris nachgewiesen, und so Goldfuß‘ Interpretationen weitestgehend bestätigt werden. Die Anwendung von RTI gestaltet sich technisch einfach und ist vielversprechend für paläontologische Studien, insbesondere bei flachen Fossilien, bei denen kleinste Unterschiede im Relief bei der Interpretation von großer Wichtigkeit sein können. Nach unserem Wissen ist diese Studie die erste bei der RTI zur Untersuchung von Weichteilen von Wirbeltierfossilien zur Anwendung kommt.

Scaphognathus crassirostris; Goldfuß; Jura; Weichteilerhaltung; Reflectance

Transformation Imaging; UV-Licht

Translator: Authors

Arabic

Translator: Ashraf M.T. Elewa

Polski

Goldfuß miał rację: zachowanie części miękkich u późnojurajskiego pterozaura Scaphognathus crassirostris pokazanych przez obrazowanie z transformacją odbiciową (RTI) i światłem ultrafioletowym oraz pomyślne początki paleo-sztuki.

Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to technika oparta na wielu cyfrowych zdjęciach z ustaloną pozycją aparatu i oświetleniem z różnych kierunków. Te zdjęcia są przetwarzane w celu utworzenia pliku graficznego, w którym pozycja źródła światła i właściwości odbicia światła mogą być modyfikowane cyfrowo. Metoda ta jest często wykorzystywana w archeologii ze względu na jej zdolność do wizualizacji szczegółów powierzchni. Tutaj stosujemy obrazowanie RTI na holotypie nieprterygodaktylowego pterozaura Scaphognathus crassirostris ze słynnego wapienia litograficznego Solnhofen z późnej jury i porównanie wyników z obrazowaniem w świetle ultrafioletowym (UV). Okaz jest szczególnie interesujący pod względem historycznym, ponieważ był to pierwszy pterozaur, dla którego powłokę "futrzastą" opisał niemiecki paleontolog i zoolog Georg August Goldfuß w 1831 r. Jego publikacja na temat tej skamieniałości zawiera szczegółowe wnioski paleobiologiczne i kończy się pierwszą opublikowaną naukową rekonstrukcją wyglądu wymarłego kręgowca w jego środowisku. Zachowanie części miękkich nie zostało jednak zaakceptowane przez późniejszych badaczy, takich jak Herman von Meyer, a prace Goldfußa dotyczące zachowania miękkich części, paleobiologii i paleo-sztuki zostały w dużej mierze zapomniane. W RTI i świetle ultrafioletowym są widoczne pyknofibryle pokrywające szyję i ciało, a także aktynofibryle i naczynia krwionośne na membranie skrzydłowej okazu Scaphognathus crassirostris, co w większości potwierdza obserwacje Goldfußa. Zastosowanie techniki RTI jest technicznie łatwe i obiecujące w badaniach paleontologicznych, zwłaszcza w przypadku płaskich skamieniałości na płytach osadowych, gdzie niewielkie różnice w reliefie mogą mieć kluczowe znaczenie. Zgodnie z naszą wiedzą jest to pierwsze badanie, w którym stosuje się RTI do badania zachowanych części miękkich w skamieniałościach kręgowców.

Słowa kluczowe: Scaphognathus crassirostris; Goldfuß; Jurajski; zachowanie części miękkich; obrazowanie transformacji odbiciowej; światło ultrafioletowe

Translator: Krzysztof Stefaniak

-

-

PE: An influential journal

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journals

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journalsArticle number: 27.2.2E

July 2024

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei