Volume 28.2

May–August 2025

Full table of contents

ISSN: 1094-8074, web version;

1935-3952, print version

Recent Research Articles

See all articles in 28.2 May-August 2025

See all articles in 28.1 January-April 2025

See all articles in 27.3 September-December 2024

See all articles in 27.2 May-August 2024

Interested in submitting a paper to Palaeontologia Electronica?

Click here to register and submit.

Article Search

Bryn J. Mader. Department of Biological Sciences and Geology, Queensborough Community College, 222-05 56th Avenue, Bayside, NY, 11364-1497, USA. bmader@qcc.cuny.edu

Bryn J. Mader. Department of Biological Sciences and Geology, Queensborough Community College, 222-05 56th Avenue, Bayside, NY, 11364-1497, USA. bmader@qcc.cuny.edu

Bryn Mader is an Associate Professor in the Department of Biological Sciences and Geology at Queensborough Community College of the City University of New York (CUNY). Prior to that, he worked at the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the State University of New York at Old Westbury. Dr. Mader received a Bachelor of Science degree from the State University of New York at Stonybrook (1982) and both a Master of Science (1987) and Ph.D. (1991) from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst. For the past thirty years his research has focused primarily on the systematics, phylogeny, and evolutionary biology of brontotheres. He was the first person to present a revision of North American brontothere species since the monumental two-volume monograph of Henry Fairfield Osborn (published almost seventy years earlier). Dr. Mader has also published papers concerning fossil horses, oreodonts, pterosaurs, and dinosaurs.

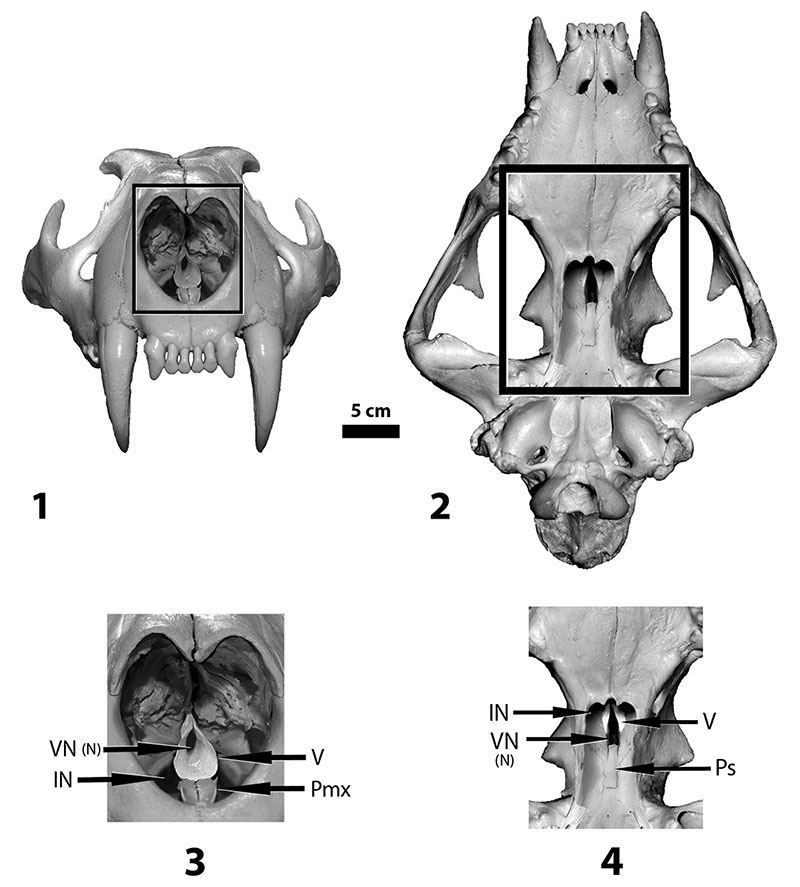

FIGURE 1. Skull of African Lion (Panthera leo, author’s private collection) showing anatomy of vomer and vomerine notch. Turbinates in this specimen are largely missing. 1, anterior view; 2, ventral view; 3, detail of anterior nasal cavity; 4, detail of internal narial region. Abbreviations: IN, internal nares; Ps, presphenoid; V, vomer; VN, vomerine notch, the presumed functional internal nares (N) in all other figures. Rectangles superimposed on upper photographs show areas of detail below. In 3 and 4 the vomer has been lightened for better clarity.

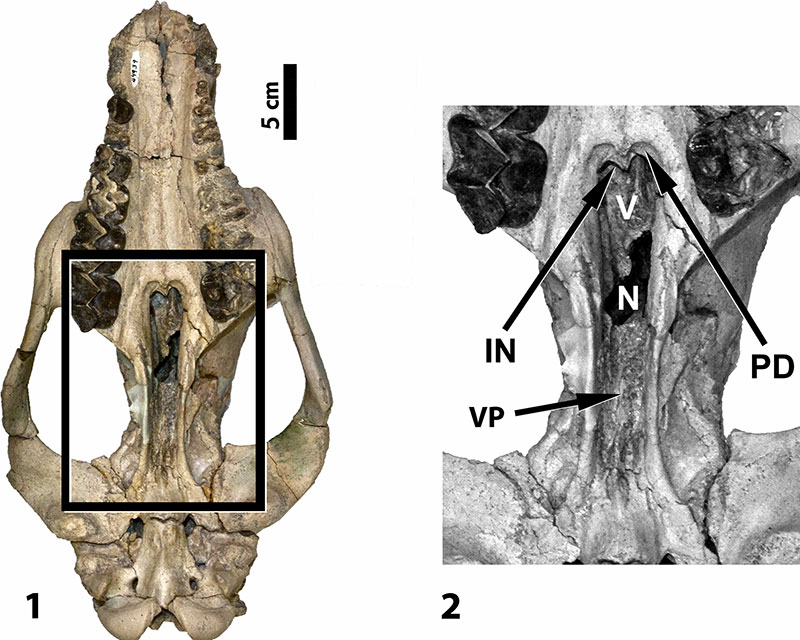

FIGURE 2. Skull of Metarhinus (UCM 44939). 1, entire skull in ventral view; 2, enlargement of the nasopharyngeal region. Rectangle superimposed on left photograph shows area of detail. Abbreviations: IN, internal nares (non-functional); N, functional internal nares (presumably the vomerine notch); PD, palatal depression (secondary palatal plate); V, vomer; VP, vomerine plate.

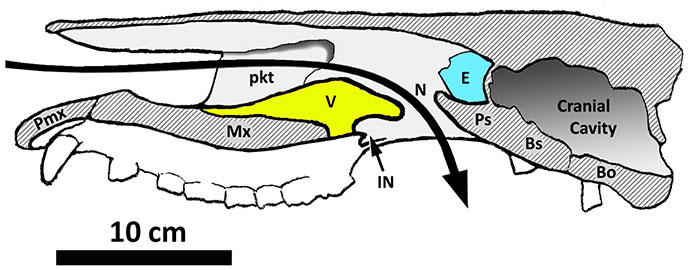

FIGURE 3. Semi-diagrammatic reconstruction of the skull of Metarhinus seen in sagittal section (based on UCM 44939 and FMNH PM 1732). Abbreviations: Bo, basioccipital; Bs, basisphenoid; E, ethmoid; IN, anatomical internal nares (non-functional); Mx, maxilla; N, functional internal nares (vomerine notch); pkt, blind pocket in lateral wall of nasal cavity; Pmx, premaxilla; Ps, presphenoid; V, vomer. Large arrow shows air pathway through the nasal cavity. Dark gray areas with hatch marks indicate cut surfaces.

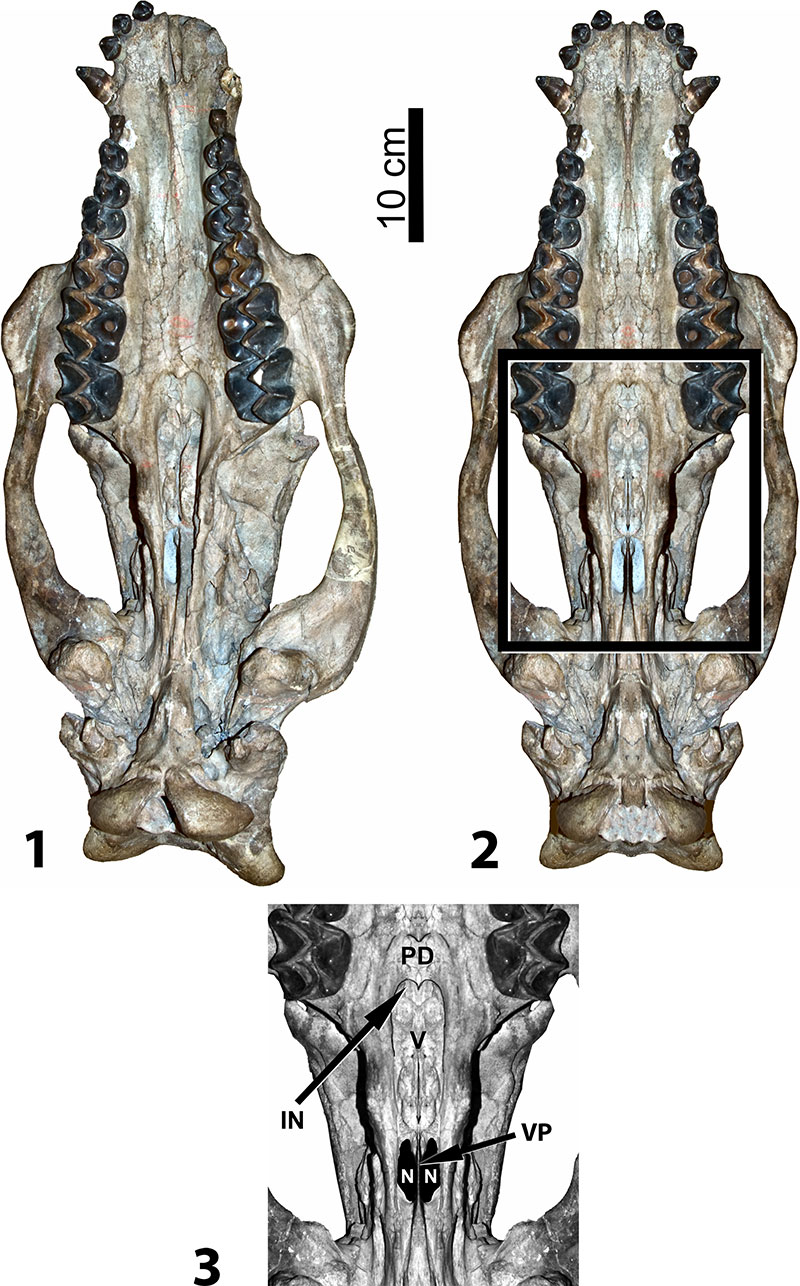

FIGURE 4. AMNH 13164, skull of Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus) in ventral view. 1, Skull as it actually appears; 2, reconstruction of skull showing how it might have appeared when fully intact and prior to taphonomic distortion; 3, detail of reconstructed internal narial region (functional internal nares darkened). Rectangle superimposed on right photograph shows area of detail. Abbreviations: IN, anatomical internal nares (non-functional); N, functional internal nares (vomerine notch); PD, palatal depression (secondary palatal plate); V, vomer; VP, vomerine plate.

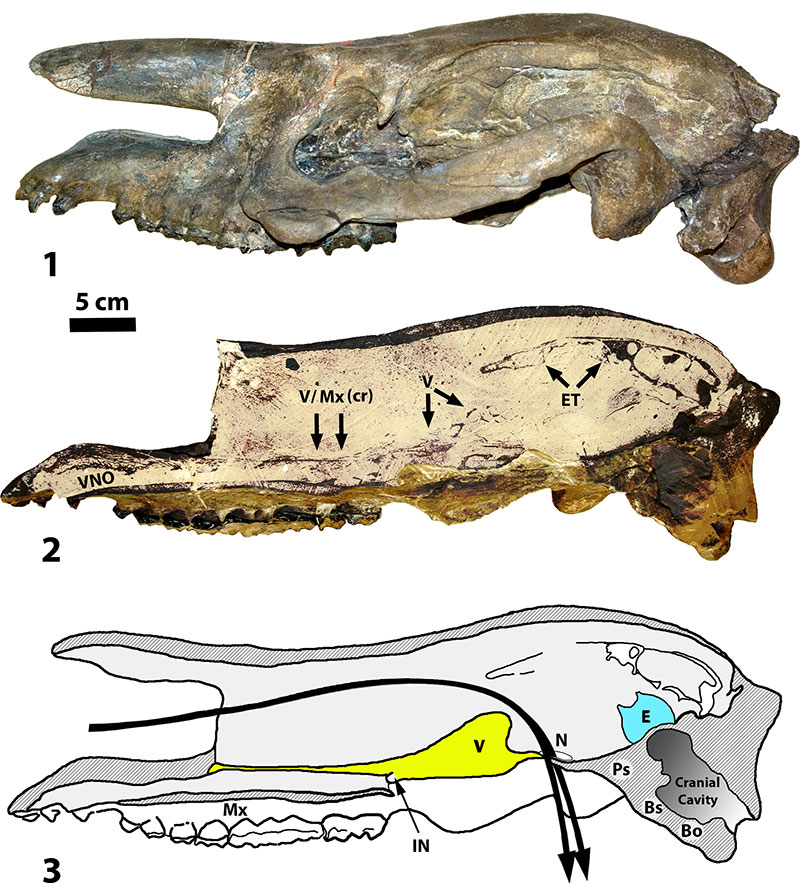

FIGURE 5. AMNH 1851, skull of Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus). 1, left side of skull showing external morphology; 2, right side of skull showing sagittal section (nasal is removed and matrix artificially lightened for better contrast); 3, semi-diagrammatic reconstruction of sagittal section showing presumed air stream. Abbreviations: Bo, basioccipital; Bs, basisphenoid; E, ethmoid; ET, ethmoturbinate; IN, anatomical internal nares (non-functional); Mx, maxilla; Mx (cr), crest of maxilla; N, functional internal nares (vomerine notch); Ps, presphenoid; V, vomer; VNO, area of vomeronasal organ.

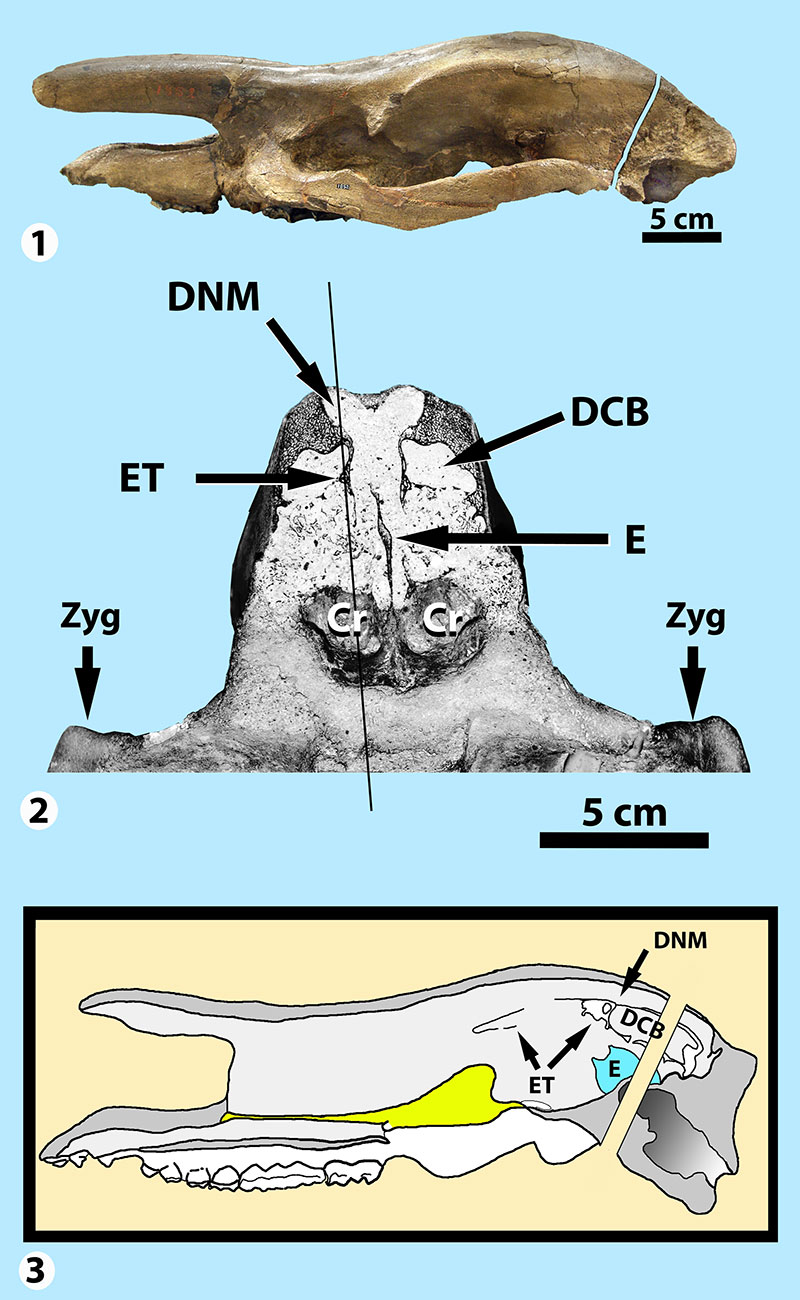

FIGURE 6. Skulls of Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus). 1, AMNH 1852 in lateral view showing location of transverse section near back of skull; 2, transverse section of AMNH 1852 through anterior-most part of braincase looking anteriorly; 3, reconstructed sagittal section of AMNH 1851 (from Figure 5.3) showing the approximate plane of the transverse section in AMNH 1852 relative to internal structures. Abbreviations: Cr, cribriform plate of ethmoid; DCB, dorsal conchal bulla; DNM, dorsal nasal meatus; E, ethmoid (perpendicular plate); ET, ethmoturbinate; Zyg, zygomatic arch. Thin diagonal line in middle image approximates the plane of the sagittal section shown in Figure 5.2.

The narial morphology of Metarhinus and Sphenocoelus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Brontotheriidae)

Plain Language Abstract

Brontotheres, also known as titanotheres, are extinct relatives of the horse and rhino that lived approximately 35-55 million years ago during the Eocene Epoch. Many brontotheres had peculiar, forked-horns, and some grew to the size of small elephants. Metarhinus and Sphenocoelus (also known as Dolichorhinus) were relatively small brontotheres with little or no horn development. Both had a highly unusual modification in their nasal anatomy, which radically changed the way they breathed. Rather than the airstream passing on either side of the nasal septum (the wall inside the nose that becomes bent in a person with a “deviated septum”), the air was channeled through its center and exited into the throat through a new opening. This anatomy is found in no other mammals known to science. It is speculated that the septum was wholly or partially divided into an upper part and a lower part and that the lower part became modified to channel air. The bone in the septum that is primarily involved in this channeling is the vomer. It is possible that this unusual arrangement was an aquatic adaptation to aid in feeding on submerged plants (water in the mouth is kept away from the airstream) or, perhaps, an adaptation to assist with the sense of smell. The latter interpretation is favored because the anatomy guides the airstream directly toward the nerve receptors in the nose that allow us to detect odors (the olfactory epithelium).

Resumen en Español

La morfología nasal de Metarhinus y Sphenocoelus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Brontotheriidae)

Los géneros de brontoterios Metarhinus y Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus) se caracterizan por un redireccionamiento inusual del paso del aire en el que los orificios nasales internos están efectivamente cerrados y han aparecido posteriormente nuevas aberturas que sirven a modo de orificios nasales internos funcionales. En lugar de pasar lateralmente hacia el vómer, la corriente de aire parece pasar sobre o a través del hueso (evitando así los orificios nasales internos anatómicos) y sale a través de una muesca del vómer agrandada. Si se interpreta correctamente, esta morfología es única entre los mamíferos. En el pasado, se ha sugerido que el desplazamiento posterior de los orificios nasales internos es una adaptación anfibia o una adaptación para mejorar el olfato. El artículo actual apoya la segunda interpretación. Entre otras razones, atendemos al hecho de que el cambio en la morfología canaliza la corriente de aire directamente hacia el epitelio olfativo en el área del etmoides. Para que el vómer canalice el aire, el cartílago septal requeriría una modificación significativa. Se especula aquí que el tabique respiratorio (vómer, cresta del maxilar superior y cresta del palatino) podría haberse aislado total o parcialmente del tabique olfativo (placa perpendicular del cartílago etmoidal y septal), permitiendo que el aire se canalizase a través de (o sobre) el vómer.

Palabras clave: titanotérido; Dolichorhinus, vómer; respirador nasal; ciclo nasal; evo-devo

Traducción: Enrique Peñalver (Sociedad Española de Paleontología)

Résumé en Français

La morphologie des narines osseuses de Metarhinus et Sphenocoelus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Brontotheriidae)

Les genres de brontothères Metarhinus et Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus) sont tous les deux caractérisés par une redirection inhabituelle des voies aériennes : les narines osseuses internes sont totalement fermées et de nouvelles ouvertures qui remplissent les fonctions de narines osseuses internes sont apparues ultérieurement. Plutôt que de passer latéralement au vomer, il semble que le flux d’air passe au-dessus ou au travers de l’os (court-circuitant ainsi les narines osseuses internes anatomiques) et qu’il sorte par une encoche élargie du vomer. Si cette interprétation est correcte, cette morphologie est unique au sein des mammifères. Dans le passé, il a été suggéré que le déplacement postérieur des narines osseuses internes était soit une adaptation amphibie, soit une adaptation pour améliorer l’olfaction. Cet article soutient cette dernière interprétation, notamment car le changement de morphologie achemine le flux d’air directement vers l’épithélium olfactif de la zone de l’éthmoïde. Pour que le vomer achemine l’air, le cartilage septal doit être extrêmement modifié. L’hypothèse est émise ici que le septum respiratoire (vomer, crête du maxillaire, et crête du palatin) a pu être complètement ou partiellement isolé du septum olfactif (plaque perpendiculaire à l’éthmoïde et au cartilage septal), permettant ainsi à l’air d’être acheminé au travers ou au-dessus du vomer.

Mots-clés : titanothère ; Dolichorhinus ; vomer ; respiration nasale ; cycle nasal ; évo-dévo

Translator: Antoine Souron

Deutsche Zusammenfassung

Die Nasenmorphologie von Metarhinus und Sphenocoelus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Brontotheriidae)

Die brontotheren Gattungen Metarhinus und Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus) zeigen beide eine ungewöhnliche Luftumlenkung: die internen Nares wurden effektiv geschlossen und es entstanden posterior neue Öffnungen, die als funktionelle interne Nares dienen. Anstatt lateral am Vomer vorbei, scheint der Luftstrom über oder durch den Knochen zu fließen (und umgeht so die anatomischen inneren Nares) und tritt durch eine vergrößerte Kerbe im Vomer aus. Richtig interpretiert, ist diese Morphologie einzigartig unter Säugetieren. In der Vergangenheit wurde vermutet, dass die posteriore Verschiebung der inneren Nares entweder eine amphibische Anpassung oder eine Anpassung zur Verbesserung der Geruchsbildung ist. Das vorliegende Papier favorisiert die letztgenannte Interpretation. Unter anderem deshalb, weil die Veränderung der Morphologie den Luftstrom direkt in Richtung des olfaktorischen Epithels im Bereich des Ethmoids leitet. Um zu erreichen, dass der Vomer Luft kanalisiert, würde die Nasenscheidewand eine wesentliche Änderung erfordern. Es wird hier angenommen, dass das respiratorische Septum (Vomer, Maxillakamm, and Palatinalkamm) ganz oder teilweise vom olfaktorischen Septum (vertikale Platte des Ethmoids und Nasenscheidewand) isoliert wurde, wodurch Luft durch (oder über) den Vomer geleitet werden kann.

Schlüsselwörter: Titanotheren; Dolichorhinus, Vomer; Nasenatmung; Atemzyklus; Evo-Devo

Translator: Eva Gebauer

Arabic

Translator: Ashraf M.T. Elewa

Polski

Morfologia okolicy nosowej u Metarhinus i Sphenocoelus (Mammalia, Perissodactyla, Brontotheriidae)

Należące do brontoteriów rodzaje Metarhinus i Sphenocoelus (= Dolichorhinus) charakteryzują się nietypowym przekierowaniem kanału powietrznego, w którym skutecznie zamknięte są nozdrza wewnętrzne, a nowe otwory, położone z tyłu, służą jako funkcjonalne nozdrza wewnętrzne. Zamiast przechodzić po bokach lemiesza, strumień powietrza zdaje się przepływać ponad lub przez kość (przez to omija anatomiczne nozdrza wewnętrzne) i wychodzi przez powiększone wycięcie lemiesza. W przypadku prawidłowej interpretacji, morfologia ta jest wyjątkowa wśród ssaków. W przeszłości sugerowano, że tylne przemieszczenie nozdrzy wewnętrznych jest adaptacją do ziemnowodnego trybu życia lub adaptacją do wzmocnienia powonienia. Pogląd zaproponowany w tej pracy sprzyja tej drugiej interpretacji. Wśród powodów jest to, że zmiana morfologii kieruje strumień powietrza bezpośrednio w kierunku nabłonka węchowego w obszarze sitowym. Aby lemiesz mógł kierować powietrze, chrząstka przegrody wymaga znacznej modyfikacji. Spekuluje się tutaj, że przegroda oddechowa (lemiesz, grzebień szczęki i grzebień podniebienia) mogła być całkowicie lub częściowo odizolowana od przegrody węchowej (blaszka pionowa chrząstki sitowej i przegrodowej), umożliwiając przepływ powietrza przez (lub nad) lemieszem.

Słowa kluczowe: tytanoteria; Dolichorhinus, lemiesz; wydech nosowy; cykl nosowy; evo-devo

Translator: Krzysztof Stefaniak

-

-

PE: An influential journal

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journals

Palaeontologia Electronica among the most influential palaeontological journalsArticle number: 27.2.2E

July 2024

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei

A Review of Handbook of Paleoichthyology Volume 8a: Actinopterygii I, Palaeoniscimorpha, Stem Neopterygii, Chondrostei