Article Search

New Species of Fish from the Genus Eosemionotus

New Species of Fish from the Genus Eosemionotus

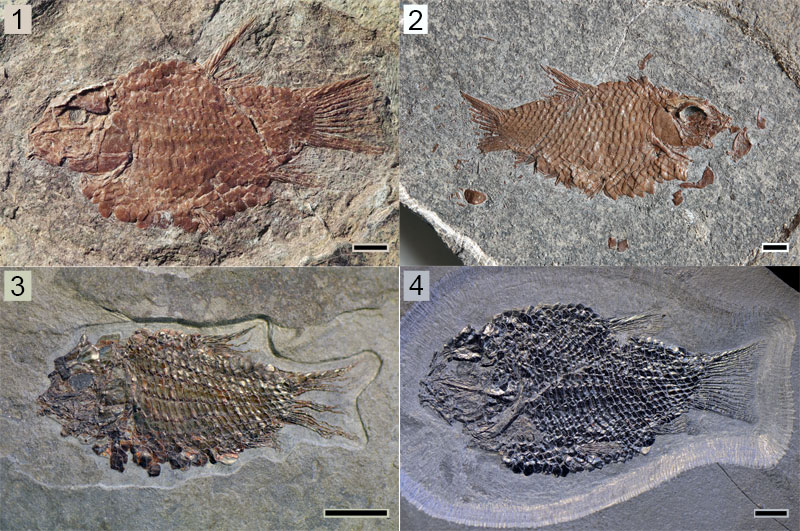

Although some fossil fish can be found in great abundance within mass mortality layers, others like the Middle Triassic genus Eosemionotus are extremely rare. For more than 80 years, Eosemionotus was known only through a single species discovered in Germany. It wasn’t until 2004 that a second species was officially published and now fifteen years after that we finally can include several new species into this once lonely genus. Dr. Adriana López-Arbarello and her team have identified three brand new species (E. diskosomus, E. sceltrichensis, and E. minutus) and have also further solidified the differences between the now five species based on their morphological variability.

Eosemionotus diskosomus. Complete specimens. 1, holotype MCSN 8082 (45 mm SL); 2, MCSN 8006 (60.5 mm SL); 3, PIMUZ T 2924 (22.5 mm SL); 4, MCSN 5617 (46.7 mm SL). Scale bars equal 5 mm.

Eosemionotus diskosomus. Complete specimens. 1, holotype MCSN 8082 (45 mm SL); 2, MCSN 8006 (60.5 mm SL); 3, PIMUZ T 2924 (22.5 mm SL); 4, MCSN 5617 (46.7 mm SL). Scale bars equal 5 mm.

Gerrhonotines, commonly known as alligator lizards, are a group of anguid lizards with a substantial fossil record as well as a diverse assemblage of species living today in North and Central America. This group of lizards has been well studied by biologists researching the molecular evolutionary history of the clade by using DNA from extant alligator lizards, but there has been a lack of reliable fossil data to take into account.

Elgaria multicarinata, photo by Scarpetta

Elgaria multicarinata, photo by Scarpetta

From approximately 62 to 10 million years ago, meat-eating mammals called Hyainailouroids roamed Africa as one of the top predators. Hyainailouroids are part of a larger group of meat-eating mammals called hyaenodonts (sorry everyone, they're NOT related to hyenas) that were found in North America, Eurasia, and Africa between 62 and 9 million years ago. Recently PE authors Matthew R. Borths and Nancy J. Stevens examined the deciduous dentition (baby teeth) of this diverse group using CT imagery. PE appreciates Borths & Stevens for taking the time to answer a couple questions about their research for the PE blog.

Here’s what the authors had to say about their recent PE publication:

Lycopsids are one of the oldest groups of vascular plants. These ancient plants only have a few living relatives still around today, the clubmosses and quillworts. Lycopsids were some of the first plants to diversify on land and their long history stretches all the back to the late Silurian period, about 425 million years ago.

Shining clubmoss, Huperzia lucidula; Wikimedia Commons

Shining clubmoss, Huperzia lucidula; Wikimedia Commons

Recently, authors Evreïnoff, Meyer-Berthaud, Decombeix, Lebrun, Steemans, and Tafforeau published an article in Palaeo Electronica about a new Late Devonian lycopsid from New South Wales, Australia. When asked about their most recent project, the authors wrote, “when studying how early land plants acquired the features that made them comparable to modern plants, Australia comes to a special place with the discovery of large leafy stems of the lycopsid Baragwanathia as early as the Late Silurian.”

“When we started [Palaeo Electronica] it was like a dare. Jump off that roof top, climb that tree, make an online journal.” – Jennifer Rumford

2017 marks the 20th anniversary of Palaeontologia Electronica (PE). For paleontologists, 20 years may not seem that long. But for the online, open-access journal PE, this represents a milestone that deserves celebration. The recently published commentary piece by Louys et al. offers a brief history of Palaeontological Electronica on the PE homepage . PE started in the early days of the internet in 1996; in fact it was one of the first peer-reviewed online academic journals in the world.

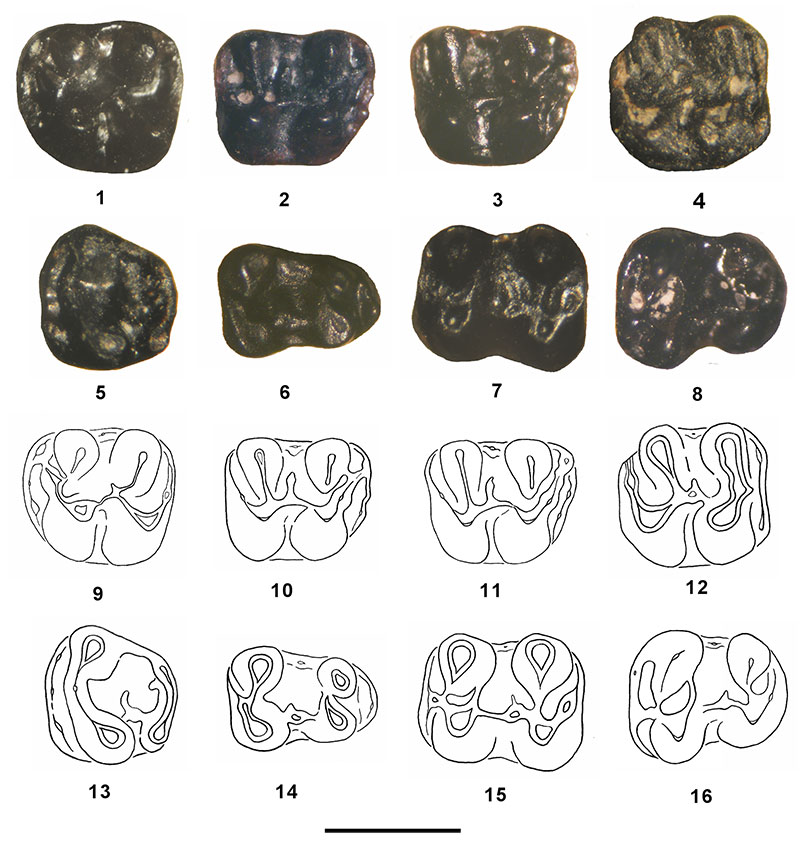

Fig 12. Elymys ? emryi new species from TBM, macrophotographs with corresponding line drawings of specimens

Fig 12. Elymys ? emryi new species from TBM, macrophotographs with corresponding line drawings of specimens

Earliest Uintan Mammals of the Bridger Basin

The Bridger Basin in southwestern Wyoming is paleontology heaven for Eocene mammal nerds like the author of this blog post. The middle Eocene Bridger Formation has yielded some of the most significant mammal fossils found in North America, including the primates Omomys carteri and Hemiacodon engardae. Distinct Bridger Formation mammals also include the strange multi-horned herbivore Uintatherium, the small weasel-shaped condylarth Hyopsodus, the giant brontotheres, carnivorous creodonts, and the blunt-toothed Stylinodon.

The fossil remains of marine mollusks have played a pivotal role in the understanding of stratigraphy around the world. Recently, Palaeontologia Electronica (PE) authors Lloyd Glawe, John Anderson, and Dennis Bell published an article about their study of microscopic mollusk shells from a set of nearly continuous cores from the Paleogene of Louisiana.

Red pandas (Ailurus fulgens) are small arboreal carnivoran mammals native to Asia that are not true pandas but are close relatives. Red pandas are unique among carnivores in many senses: they spend much of their time in trees, they eat mostly bamboo, and they practice a polygamous (both males and females have multiple mates) mating system with little male-male competition. This mating system has historically been pointed to as the reason for the monomorphism between the sexes (males and females are the same size), a rare character not seen in many other carnivores. Considering this polygamous mating system is unusual amongst carnivores, the natural question that comes to mind is when and why did this shift occur in ailurids?

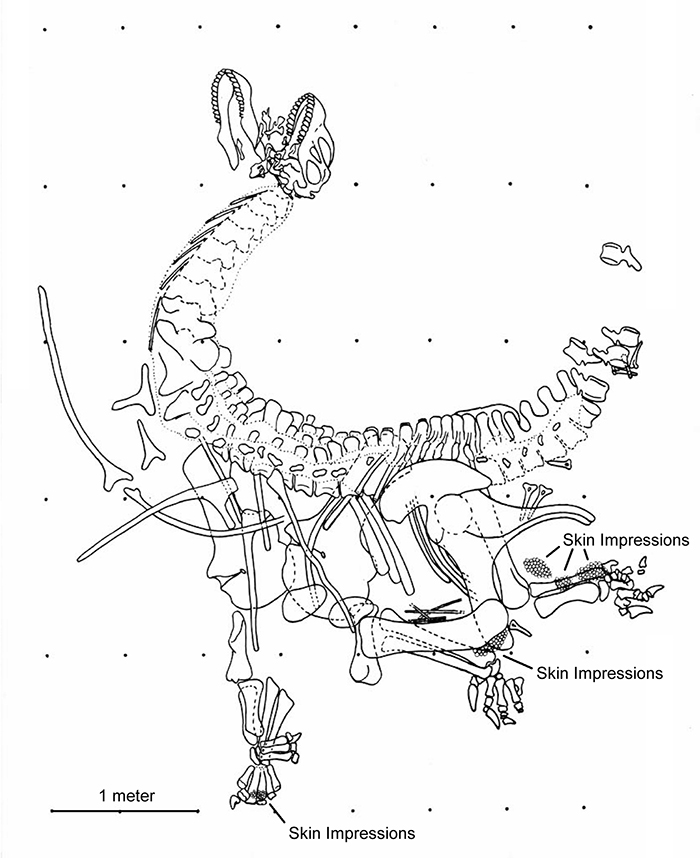

Sauropods are some of the most iconic dinosaurs and images of these long-necked giants are frequently featured in the popular media. One type of sauropod, Camarasaurus, is one of the most common dinosaurs of northern America. You might think that paleontologists would know this dinosaur from head to foot because it so ubiquitous, but in reality those toes have remained quite the mystery.

Detailed quarry map of the specimen SMA 0002 excavated in 1992-93 at the Howe-Stephens Quarry

Detailed quarry map of the specimen SMA 0002 excavated in 1992-93 at the Howe-Stephens Quarry

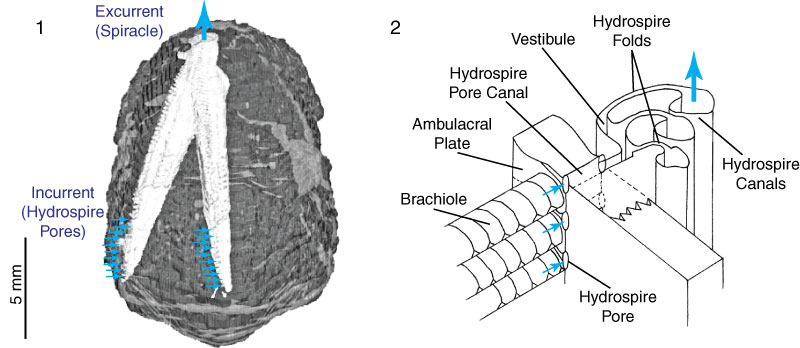

Blastoids are an extinct group of bottom-dwelling echinoderms (closely related to sea urchins

and sea stars). These sea creatures had extremely complex skeletonized respiratory structures

that have had scientists curious for years about how fluids moved through their bodies.