Article Search

BByBy Hannah BirdHannah Bird

Symbiotic relationships, where two organisms closely co-exist, are usually considered beneficial for both parties. But when one takes advantage of the other, parasitism dominates. Remarkably, both of these relationships can be seen in the fossil record from millions of years ago.

Symbiotic relationships, where two organisms closely co-exist, are usually considered beneficial for both parties. But when one takes advantage of the other, parasitism dominates. Remarkably, both of these relationships can be seen in the fossil record from millions of years ago.

Hannah Bird

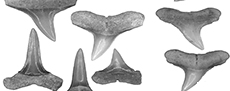

Picture a face-off between a giant shark and small whale in the Miocene oceans 15 million years ago and you may think you know the ending. But fossil remains found in the Calvert Cliffs, Maryland, USA, reveal a different story – one of tenacity and survival.

Hannah Bird

Whilst indulging in a summer picnic or barbeque we may consider flies bothersome, but have you ever contemplated their evolution? Incredibly, many of their genera have astonishing longevity, establishing themselves in the Middle Triassic (247 to 237 million years ago) and with some living species existing for millions of years. There are 161 families of flies today, living in almost all environments on Earth. Perhaps it’s time to regard them a little more kindly and that is exactly what researchers from the Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., and their collaborators, have done for the last decade.

Kerste Milik

Fossil collecting is a rewarding and educational hobby enjoyed by people of all ages, but paleontologist opinions on amateur collecting are mixed. A new study in Palaeontologia Electronica highlights the invaluable contributions of amateur fossil collectors to vertebrate paleontology, providing recommendations to improve this essential collaborative relationship.

The people of PE are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of one of our own, Patrick Getty, who worked for many years as a Handling Editor (2017-2021). Patrick's careful and thorough efforts to work with our authors were appreciated and are greatly missed.

The people of PE are deeply saddened to learn of the passing of one of our own, Patrick Getty, who worked for many years as a Handling Editor (2017-2021). Patrick's careful and thorough efforts to work with our authors were appreciated and are greatly missed.

A link to a remembrance from University of Connecticut

https://geosciences.uconn.edu/alumni/#

A giant, crocodile-like predator lurked in North American wetlands during the Late Triassic, dominating the food chain. But even this mighty creature, Smilosuchus gregorii, could not escape the threat of disease.

“The natural world has always been harsh and unforgiving,” said Dr. Andrew Heckert, a paleontologist at Appalachian State University.

It was a fearsome predator that filled the oceans with fear. It was a shadow; a phantom from the depths that eluded the watchful crab, the anxious guppy until… it was too late! It was a prowler. A monster! A marine horror that menaced its fellow denizens of the deep as a living, breathing nightmare! It was…

This Shark Week, let's celebrate the amazing work of paleontologists who continue to piece together the long and fascinating story of sharks' past.

Sharks have been around for over 400 million years, long before the dinosaurs, and we're still learning more every day about their impressive history.

From a 20-meter megalodon to an ancient shark nursery, here’s our roundup of all the biggest recent shark discoveries published here in Palaeontologia Electronica, all of which are open-access papers, always free for anyone to read!

It was a rough-skinned leviathan of biblical proportions. An epic fish tale to end all fish tales. A star of the silver screen. A true monster of the deep. Or was it? Despite megalodon (Otodus megalodon) being cemented in the popular imagination as the most massive shark of all time, a gargantuan set of jaws strapped onto a nuclear submarine, concrete details about the animal’s actual size are shrouded by the depths of time and poor preservation. Sharks, unlike bony fish and land-dwelling vertebrates, do not possess an ossified skeleton. Instead, shark bodies are supported by cartilaginous (made of cartilage) skeletons - a skeleton to be sure, but not one that preserves nearly as well as calcium-rich bones as one finds in other fish, amphibians, mammals, birds, and reptiles. As a consequence of this skeletal arrangement, whole body fossils of prehistoric sharks are exceedingly rare. Many species are known only from body elements that do preserve, mainly teeth. Megalodon is one such species. As of the writing of this blog, no whole body fossils of Otodus megalodon are known to science.

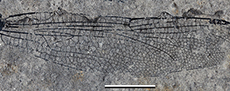

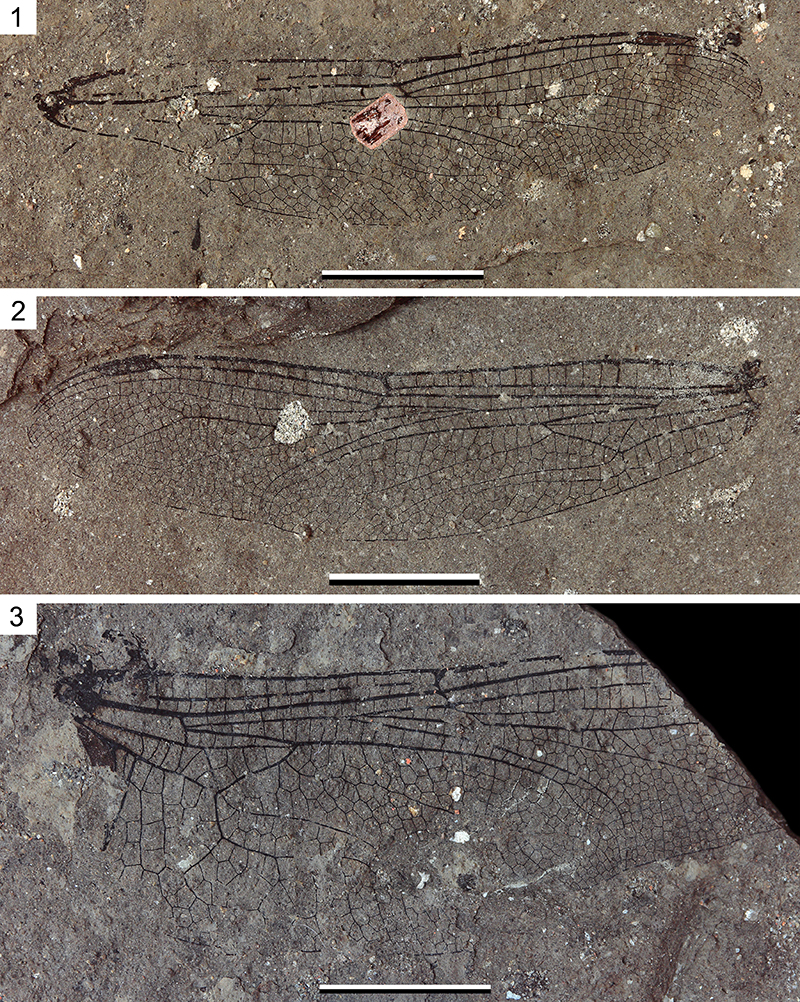

Small creatures can often provide big insights into past worlds. A recent paper published in Palaeontologia Electronica describes ten fossil Odonata (dragonflies and their relatives) wings from the Oligocene palaeolake Enspel. These wings, along with several well-preserved naiads (larval dragonflies), help paint a picture of a vibrant, Figure 1. Nel et al. 2021 used the venation in wings such as these to identify different subgroups within Odonata. and buzzing, lost world in what is today southwestern Germany.

Figure 1. Nel et al. 2021 used the venation in wings such as these to identify different subgroups within Odonata. and buzzing, lost world in what is today southwestern Germany.

The palaeolake Enspel, according to André Nel, one of the researchers on the study, was “a freshwater lake with water of rather good quality, oligotrophic, high oxygen level probably, with a rich aquatic fauna, under a climate warmer than today, thus with a rich entomofauna.”

- A Fossil Collection Inspection: Examining Anthropogenic Bias in Fossil Collections

- A "Cave" Undertaking: Raptor Pellets Shed Light on Cuba’s Recent Past

- Fossil Spiders from an Ancient Lake

- How Often Did Spinosaurs Replace Their Teeth?

- Trilobites’ Bites: Fossil Wounds Hidden Among Dinosaurs

- Spirals, Spirals Everywhere: Measuring Logarithmic Spirals in Nature

- Relatives or Lookalikes? Mesozoic Crab Fossils Highlight Challenge of Convergent Evolution

- From Biting to Baleen: Paleontologists Trace the Evolution of Marine Mammal Feeding

- Eocene Tube Worms

- Marine Animals Tough it Out During Ice Age

Kerste Milik

Kerste Milik