Article Search

Using the Pleistocene to Predict the Future

Using the Pleistocene to Predict the Future

The Pleistocene landscape, 2.6 million-11,700 years ago, would have been largely recognizable, boasting many familiar plant and animal species still around today. This was also the time when our very own Homo sapiens human ancestors first evolved and spread across the world.

The climate experienced several glacial cycles through what is commonly known as the ‘Ice Ages’ and is best known for the large megafauna roaming the landscape, which included mammoths, mastodons, saber-toothed cats, and giant ground sloths!

Historical Documents Unearthed in Tübingen, Germany

Historical Documents Unearthed in Tübingen, Germany

A recent PE article reveals the contents from the historical archive of the palaeontological collection in Tübingen, Germany. An assortment of letters, notes, drawings, photos and various other documents dating back to some of the founding fathers of German palaeontology of the nineteenth and twentieth century are now available to both the public and researchers.

Ingmar Werneburg has been the collections curator for Tübingen since 2016, when he happened upon a cabinet full of these assorted documents. Along with his former assistant, Juliane Hinz, the next year was spent examining, sorting, and cataloguing over 1,300 items which highlighted the history of the Tübingen collections.

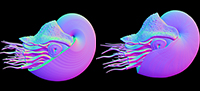

The Key to Cephalopod Diversity and Success

The Key to Cephalopod Diversity and Success

Cephalopods are a class of mollusks that include highly intelligent octopuses, scary squid, camouflaging cuttlefish, and the chambered nautilus (Family: Mollusca, Class: Cephalopoda). The nautilus, Nautilus pompilius, is among the last living cephalopods with an external shell which is full of chambers. Throughout the Paleozoic Era (544-245 million years ago), all cephalopods had an external shell that came in a variety of shapes and sizes.

A challenge for cephalopods with an external shell is achieving neutral buoyancy. This is the goal SCUBA divers also aim to achieve, to become weightless underwater and able to float in place without sinking or rising. For a cephalopod, this allows them to swim more efficiently and travel farther out into the ocean from shore.

The Devonian Monster of the Deep

The Devonian Monster of the Deep

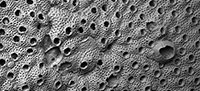

The Devonian Period, known as ‘The Age of Fishes’, happened between 419-358 million years ago. The earth during this time was a warm global greenhouse environment where the first land plants were diversifying across two large continents named Euramerica and Gondwana. Even the first tetrapods (vertebrates with four limbs), our ancient ancestors, crawled out of the sea onto land during this time. The oceans flourished with life. Brachiopods, trilobites, and armoured fish (placoderms) were plentiful, and reefs blanketed shallow seaways. The reefs of the Devonian were much different than those we know today. Although there were some corals, reefs were primarily made up of sponges called stromatoporoids.

Such an environment was ideal for a large predator to reign king and one such predator was the Dunkleosteus. Dr. Zerina Johanson, an expert on Devonian fishes describes the formidable fish:

“Like all placoderm fish, the head and front part of the body in Dunkleosteus were covered in bony plates. It was clearly predatory, with jaws being dominated by large shearing surfaces. The reconstructed tail suggests it moved like fast-swimming sharks do today, indicating it was a speedy predator.”

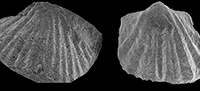

Brachiopod Faunas Through the Hangenberg Crisis (Devonian-Carboniferous)

Jaleigh Pier

Mass Extinction events capture our attention. Whether it’s because of the astounding loss of life, incredible climactic events, or vast environmental differences compared to our modern world, they fascinate us. These events are extremely rare, having only occurred five times over the course of Earth’s 4,500,000,000 year history which are formally known as the ‘Big Five’. Although these get most of the attention, there have been many other ‘crisis’ events that still triggered significant losses of life.

The Lapara Creek Fauna – A snapshot of Texas 10 - 12 million years ago

The Lapara Creek Fauna – A snapshot of Texas 10 - 12 million years ago

Between 10 - 12 million years ago, the Texas Gulf Coast could be described as a “Texas Serengeti” – with specimens including elephant-like animals, rhinos, alligators, antelopes, camels, 12 types of horses and several species of carnivores. In fact, over 4000 specimens representing 50 animal species, from The Lapara Creek Fauna (from the Goliad Formation) near Beeville, Texas, have recently been identified by Dr. Steven R. May from The University of Texas at Austin Jackson School of Geosciences.

Many of these specimens were collected by employed fossil hunters over 80 years ago as part of the State-Wide Paleontologic and Mineralogic Survey of Texas between 1939 and 1941. Despite a number of scientific papers having been published on select groups of these fossils, Dr. May’s paper is significant in that it is the first to describe this fauna in its entirety.

Leaf Cuticle Reveals Effects of Climate Change on New Zealand Forests

Leaf Cuticle Reveals Effects of Climate Change on New Zealand Forests

It is well known that changing climate affects the distribution and range of species, where they often ‘track’ conditions most favorable to them. For example, as temperatures warm today, species are moving up slopes and poleward to what had been cooler climates. Glacial-interglacial cycles provide a unique experiment where one can observe a community in the same location, through both cold and warm conditions, comparing how they have changed over time. In the case of vegetation, the warmer interglacial periods provide a window of recovery, however interglacial communities can vary greatly in composition and even soil conditions, providing an interesting history to study in one location over time such as the northern island of New Zealand.

Palynology is the study of pollen and spores, which can help indicate the presence and range of plants both past, through the rock record, and present since related groups produce similarly shaped grains. Pollen is produced in copious amounts and light enough to be dispersed via wind, water, or even animal transport making presence and range estimates for vegetation more generalized. Another way to detect plant presence is by observing leaf cuticle, the waxy outer layer of plant leaves which preserves unique characteristics of each plant species.

Why the strange nose? The peculiar case of Metarhinus and Sphenocoelus

Why the strange nose? The peculiar case of Metarhinus and Sphenocoelus

Brontotheres (also known as titanotheres; Family BRONTOTHERIIDAE) are a family of extinct relatives of the horse and rhinoceros that lived approximately 35-55 million years ago in what is now North America and Asia. They lived during a period of time known as the Eocene Epoch (56 to 33.9 million years ago). Many had peculiar, forked-horns. Some grew to the size of small elephants. The low-crowned teeth of members of the family suggest that they were obligatory browsers (leaf-eaters). They inhabited forested regions, although the very large forms of later times (Chadronian, the latest age in the Eocene Epoch) would probably have inhabited more open meadow-like ground.

Two genera Metarhinus and Sphenocoelus (also known as Dolichorhinus) are particularly interesting. Members of the two genera were relatively small compared to most brontotheres and had little or no horn development. Species of Metarhinus were about the size of a tapir and while species of Sphenocoelus were a little larger. However, it is their usual nasal anatomy which radically changed the way they breathed that is completely unique and found in no other creatures known to science.

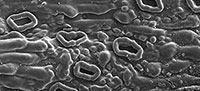

Bryozoans Described for the First Time from the Tamiami Formation (USA)

Bryozoans Described for the First Time from the Tamiami Formation (USA)

Jaleigh Pier

Bryozoans are tiny colonial animals that have a mineralized skeleton which typically encrusts onto hard surfaces in aquatic environments including rocks and shells. Dr. Emanuela Di Martino is a bryozoan specialist and describes them best:

“Bryozoans are small, aquatic, colony-forming invertebrate animals often mistaken for corals or seaweed. Each colony is comprised of genetically identical modular units called zooids. While zooids are microscopic, bryozoan colonies can range in size from a few millimetres to more than a metre wide.”

Like the cells of living sponges, bryozoan zooids have diverse forms and functions. There are specialized zooids for feeding, being either male or female for reproduction, and even those specific for defense called avicularia. Their physical appearance depends on their specific function within the colony. The great majority of bryozoans secrete calcareous skeletons, creating a lengthy fossil record dating back to the early Ordovician, about 475 million years ago.

Eternal Loving Embrace of Two Eocene Moths

Eternal Loving Embrace of Two Eocene Moths

For the average person, insects trapped in amber may spark images from the film Jurassic Park, where mosquitos were the key to resurrecting living dinosaurs. Although collecting dino DNA from fossil insects may not be feasible, there is still much to learn from these specimens frozen in time.

Dr. Thilo C. Fischer and Dr. Marie K. Hörnig are passionate palaeoentomologists (the study of fossil insects) and are beyond excited to share their fascinating discovery with the world! Not only did they find two individual moths (Order: Lepidoptera) trapped together in Baltic amber dating back 56-33 million years ago (Eocene), but they were a mating pair in copula! This is an extremely rare finding for any insect group and a first for the group Lepidoptera.

- New Species of Fish

- BLOG: Earliest fossil of Elgaria

- PE Blog: Deciduous Hyaenodont Teeth

- BLOG: Devonian lycopsid cone

- BLOG: Twenty Years Online!

- BLOG: Earliest Uintan Mammals

- BLOG: NW Louisiana mollusk features

- BLOG: Dimorphism in Pristinailurus

- BLOG: Manus and pes of Camarasaurus

- BLOG: Blastoid hydrospire fluid flow