First butterfly (Papilionoidea) from Baltic amber by a characteristic egg pinpoints an Eocene minimal age of admirals (Nymphalidae: Limenitidinae) — a distinct step in the rise of the Papilionoidea

First butterfly (Papilionoidea) from Baltic amber by a characteristic egg pinpoints an Eocene minimal age of admirals (Nymphalidae: Limenitidinae) — a distinct step in the rise of the Papilionoidea

Article number: 28.1.a10

https://doi.org/10.26879/1407

Copyright Palaeontological Association, February 2025

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Submission: 19 May 2024. Acceptance: 8 February 2025.

ABSTRACT

Inclusions in Eocene Baltic amber have been studied for a long time and manifold taxa, predominantly Arthropoda, have been scientifically described from it, also new orders. With respect to the insect order Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) there have not yet been indisputable finds of butterflies. However, phylogenetic studies and direct fossil evidence from older sediments indicate that butterflies in a broad sense (Rhopalocera, comprising the Papilionoidea) have older origin as evidenced by a Hesperiidae from the Paleocene of Fur, Denmark (Kristensen and Skalski in Kristensen, 1999; de Jong, 2017). Earliest known Papilionoidea (butterflies in a strict sense) are from the Eocene Green River Shale of Colorado (Durden and Rose, 1978). Chazot et al. (2019) calculated the origin of butterflies (Papilionoidea) by divergence analyses with molecular data at between 89.5 and 129.5 mya with a median at 107.6 mya, corresponding to latest Early Cretaceous. This strongly supposes that butterflies also have been present in the Eocene Baltic amber forest ecosystem. Here, we report on first reliable fossil record of butterflies in Baltic amber. The find of an egg inclusion with a characteristic hexagonal sculpture can be identified as a Papilionoidea egg. Among these it can be affiliated to the subfamily Limenitidinae of Nymphalidae. Best known extant relatives of the find are butterflies of the genus Limenitis, admirals. The Eocene minimal age for Limenitidinae provides one of the few known calibration points by direct evidence at 33.9--37.8 mya for Baltic amber. The delicate eggshell structures have developed surprisingly early but then turned out to be quite conservative.

Thilo C. Fischer. Volunteer at Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Münchhausenstraße 21, 81247 Munich, Germany. thilo.c.fischer@gmx.de

Axel Hausmann. The Bavarian State Collection of Zoology, Münchhausenstraße 21, 81247 Munich, Germany. hausmann.a@snsb.de

Keywords: calibration point; inclusion; Lepidoptera; new genus; new species

Final citation: Fischer, Thilo C. and Hausmann, Axel. 2025. First butterfly (Papilionoidea) from Baltic amber by a characteristic egg pinpoints an Eocene minimal age of admirals (Nymphalidae: Limenitidinae) — a distinct step in the rise of the Papilionoidea. Palaeontologia Electronica, 28(1):a10.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1407

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2025/5454-first-butterfly-in-baltic-amber

Copyright: February 2025 Palaeontological Association.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

https://zoobank.org/5B707C25-4BB2-4BE9-8061-8FD032101D8C

INTRODUCTION

The fossil record of Lepidoptera is sparse, most likely for their most delicate structures and unfavorable taphonomy. But some time ago, the fossil record of Lepidoptera was reviewed thoroughly (Sohn et al., 2012; Sohn and Lamas, 2013; de Jong, 2017). Structures allowing for systematic affiliation are most likely to be preserved in ambers. However, there is strong bias against the preservation of larger adults, such as Papilionoidea (butterflies) and Macroheterocera. Macroheterocera records from ambers are from the family Geometridae, caterpillars (Grimaldi and Engel, 2005; Fischer et al., 2019) and a moth from Dominican amber (Sarto i Monteys et al., 2022). To date, butterflies in amber are known from Dominican amber, but not at all from Baltic amber (Grimaldi and Engel, 2005; Sohn et al., 2012; Sohn and Lamas, 2013). Here, we provide by a characteristic fossil egg a first record and a description of a member of the subfamily Limenitidinae (Nymphalidae, Papilionoidea). Fossil evidence for the genus Limenitis up to now is only from the Pliocene of Willershausen (Germany) by a forewing and partial thorax preserved in lacustrine sediments (Branscheid, 1977; Brauckmann et al., 2001; Sohn et al., 2012). Furthermore, resemblance to Limenitis was discussed by Comstock (1961) for Apanthesis leuce described from the Late Eocene Florissant Beds (Scudder, 1889). For the genus Neptis there seems to be no fossil evidence at all. The butterfly egg described here is an isolated finding, without association to other Lepidopteran remains or other syninclusions in this piece of Baltic amber, except stellate trichome hairs from leaves typical for this amber. Nevertheless, it may serve as another piece of information in the scarce fossil record of butterflies.

GEOLOGICAL SETTINGS / STUDY AREA

Baltic amber comes from Upper Eocene deposits (Prussian Formation, “Blue Ground”); the facies is that of lagoonal deltas, which embedded resin from forests over large areas of the Scandinavian and Baltic regions (Kharin and Eroshenko, 2017). Economically, the largest mine is that of Kaliningrad, where also most amber inclusions and the one described here originate.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Authentication of the amber inclusion is ensured by purchase from a trusted salesperson known by long-term relations. The amber also contains a stellate trichome as a syninclusion with a typical form for Baltic amber. The amber shows the characteristic blue fluorescence with UV light. The pictures of the egg were produced by a stacked imaging approach. The specimen is kept at constant temperature in a plastic clip bag within a metal box, excluding excess oxygen and light, in the author’s TCF collection under # 8660. It will be transferred as a holotype kept at the Bavarian State Collection of Zoology (# SNSB-ZSM-LEP amb012).

RESULTS

Systematic Palaeontology

Family NYMPHALIDAE Rafinesque, 1815

Taxon. Genus EOLIMENITIS gen. nov.

zoobank.org/6927C70F-A381-4EC4-99D5-1AFF0F566A6E

Species. Eolimenitis baltica nov. spec.

zoobank.org/EFB714D1-BD24-47BB-BCCE-BD2370C8499C

Name. Etymology: “limenitis” refers to the subfamily Limenitidinae. The prefix “Eo” in the genus name refers to the Greek word for (the godness of) dawn “Eos”. The genus Eolimenitis might also been used for future finds fossil eggs of Limenitidinae of other ages than Eocene. The species name 'baltica' refers to the occurrence in Baltic amber and to the locus typicus.

Typus.Holotypus: Specimen SNSB-ZSM-LEP amb012.

Locus typicus: Amber mine of Yantarni, RU.

Stratum typicum: “Blaue Erde” (Upper Eocene to Lower Oligocene).

Repository: Bavarian State Collection of Zoology SNSB-ZSM-LEP amb012.

Diagnosis of genus. The genus Eolimenitis is established for fossil forms of the subfamily Limenitidinae and is currently only based on the egg phenotype. The fossil Eolimenitis egg - as described below - closely resembles eggs of the genera Limenitis, Neptis, Parthenos, and Adelpha (all Limenitidinae). The high number of 400 - 500 hexagonal fields seems characteristic in comparison to extant Limenitidinae. In genus Adelpha, the number of hexagonal fields can reach 100 - 200 (Cossey, online resource), in Limenitis this is much lower (Döring, 1955).

Description of species. The general shape of the egg is a slightly elongated spheroid (Figure 1).

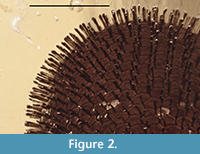

An irregular structure which, due to its position in amber is hardly visible, may represent the micropyle. Polishing of the batch of amber with this piece had touched the inclusion’s surface, leading to partial filling of its cavity with white polishing powder. The surface of the egg is characteristically structured by a hexagonal pattern with fields of approx. 100 µm in diameter. Every corner of three-fields-joining carries a 130 µm spike, which is 10 µm thick and has a clubbed end of 15 µm in diameter (Figure 2). The total of hexagonal fields can be estimated to 400-500.

An irregular structure which, due to its position in amber is hardly visible, may represent the micropyle. Polishing of the batch of amber with this piece had touched the inclusion’s surface, leading to partial filling of its cavity with white polishing powder. The surface of the egg is characteristically structured by a hexagonal pattern with fields of approx. 100 µm in diameter. Every corner of three-fields-joining carries a 130 µm spike, which is 10 µm thick and has a clubbed end of 15 µm in diameter (Figure 2). The total of hexagonal fields can be estimated to 400-500.

Orientation of the egg’s micropylar axis to the substrate, whether upright (perpendicular to substrate) or flat (parallel) (for definition of types see Chapman, 1896), could not be determined, as the egg is an isolated find without substrate at all.

Taphonomy. The inclusion is preserved in a piece of clear Baltic amber 12 mm x 9 mm x 7 mm in size. It is 2 mm long with its large diameter. The only syninclusion is a stellate trichome, as often observed from Baltic amber.

Systematic Identification

The inclusion was first supposed to be a Lepidoptera egg and, subsequently, as an egg of the genus Limenitis or closely related taxa. In parallel, also a wider systematic approach for confirming its identification was taken. Eggs of all lepidopteran families and genera for which pictures of eggs are available at Lepiforum and those reported by Döring (1955) were checked. After an initial screening hit with Limenitis eggs (Limenitidinae) further focus was set on the other subfamilies of Nymphalidae, namely Heliconiinae, Apaturinae, Nymphalinae, Charaxinae, Satyrinae, Danainae, and Libytheinae (Dhungel and Wahlberg, 2018). Only among Nymphalidae - Subfamily Limenitidinae Behr, 1864 - tribes Limenitidini Behr, 1864 (admirals, german “Eisvögel”), Neptini Newman, 1870 (“Trauerfalter”), and Parthenini Reuter, 1896 (“Blaue / Braune Segelfalter”) eggs comparable to the fossil find could be found. Eggs of the genera Limenitis Fabricius, 1807, Adelpha Hübner, 1819 (Limentitidini), Neptis Fabricius, 1807, and Parthenos Hübner, 1819 were found to show a highly similar sculpture of hexagonal plates with spikes with clubbed ends at every corner of the hexagons (for Adelpha and Partenos, pers. comm. A.V.L. Freitas, 2024; Willmott, 2003). Similar egg figures were examined from Limenitis populi, L. camilla, L. reducta, Neptis sappho, and N. rivularis (Lepiforum, 2022). The same results from the study of Döring (1955) who presented accurate and detailed figures for the eggs of 618 European Lepidoptera species. The character “hexagonal egg pattern with clubbed spikes” was only found within Limenitidinae in this study and has been described as a synapomorphy for the subfamily Limenitidinae (Freitas et al., 2004).

The inclusion was first supposed to be a Lepidoptera egg and, subsequently, as an egg of the genus Limenitis or closely related taxa. In parallel, also a wider systematic approach for confirming its identification was taken. Eggs of all lepidopteran families and genera for which pictures of eggs are available at Lepiforum and those reported by Döring (1955) were checked. After an initial screening hit with Limenitis eggs (Limenitidinae) further focus was set on the other subfamilies of Nymphalidae, namely Heliconiinae, Apaturinae, Nymphalinae, Charaxinae, Satyrinae, Danainae, and Libytheinae (Dhungel and Wahlberg, 2018). Only among Nymphalidae - Subfamily Limenitidinae Behr, 1864 - tribes Limenitidini Behr, 1864 (admirals, german “Eisvögel”), Neptini Newman, 1870 (“Trauerfalter”), and Parthenini Reuter, 1896 (“Blaue / Braune Segelfalter”) eggs comparable to the fossil find could be found. Eggs of the genera Limenitis Fabricius, 1807, Adelpha Hübner, 1819 (Limentitidini), Neptis Fabricius, 1807, and Parthenos Hübner, 1819 were found to show a highly similar sculpture of hexagonal plates with spikes with clubbed ends at every corner of the hexagons (for Adelpha and Partenos, pers. comm. A.V.L. Freitas, 2024; Willmott, 2003). Similar egg figures were examined from Limenitis populi, L. camilla, L. reducta, Neptis sappho, and N. rivularis (Lepiforum, 2022). The same results from the study of Döring (1955) who presented accurate and detailed figures for the eggs of 618 European Lepidoptera species. The character “hexagonal egg pattern with clubbed spikes” was only found within Limenitidinae in this study and has been described as a synapomorphy for the subfamily Limenitidinae (Freitas et al., 2004).

Ackery et al. in Kristensen (1999) reported on the specific structure of eggs of genera related to Limenitis: “While eggs of many Limenitini [sic!] are characteristically spined, appearing like ‘minute sea urchins’ (Corbet and Pendlebury, 1992), those of other subgroups....... are variable in form, without spines.”

Eggs of Limenitis and Neptis are about 0.9 mm in diameter (Natur-in-NRW online resource). The fields of the hexagonal pattern, however, have about the same size of 100 µm in diameter. The fossil egg has about a 2.2-fold diameter as in extant species, and, hence, correspondingly larger number of fields and spikes. There are some 400-500 fields, which is higher than in extant Limenitidinae. Closest is Adelpha, the number of hexagonal fields some 100-200 (Cossey, online resource).

DISCUSSION

With respect to careful examination, it must be considered if the inclusions could represent some other structure rather than an egg, like a compound eye of an insect. Also compound eyes are known to show hexagonal surface structure and compound eyes can bear setae between the ommatidia (e.g., honeybee, Drosophila, Noctuidae/Hadeninae). However, the number of hexagonal fields in compound eyes is much larger and the setae - if present - are much finer and longer and not clubbed. Most importantly, the whole inclusion is an almost complete globular structure, showing no attachment zone at all. Moreover, the borders of the hexagonal fields are notched rather than bulged over the surface. Consequently, the interpretation as a compound eye can be excluded.

Accepting the inclusion as an insect egg, it must be considered that this might belong to another order than Lepidoptera. However, screening through the internet, study of literature and asking advice from expert entomologists did not result in finding any alternative explanation for our inclusion. Therefore, we conclude here the egg belonging to Limenitidinae.

The egg is a single specimen from a collection with some 1400 Lepidopteran inclusions from Baltic amber. Eggs of moths (so called “Microlepidoptera”), in contrast, do occur in Baltic amber rarely. They are often associated with females of all abundant Baltic amber Lepidoptera families and genera. Findings of female adults with eggs are from cf. Gracillariidae (Gracillariites sp.) (2 specimens), Elachistidae (1), Oecophoridae (6), Depressariidae (1), Tineidae (7), and Gelechiidae (1, Bitterfeld amber) in the considered collection. Furthermore, there are two isolated finds of moth eggs, one of these caught in a spider web in the collection examined. It is unclear if the eggs, which are found in close relation to those female moths, are examples of egg laying caught in the act by the flowing resin (“frozen behaviour”) or, instead, being induced by the resin itself as a reaction and an attempt to save the eggs, or are due to a post-mortem process. Extant Limenitidinae are not known to feed on resin-producing plants. The presented butterfly egg is a single find, without even associated Lepidopteran scales or remains of leaves or other substrate from egg deposition. The egg could also have been transported onto the resin via air or water.

For the genera Limenitis and Neptis, egg deposition on the respective narrow range of feed plant taxa is described and fossil association with such leaves might have been expected. However, like with adults of butterflies there is a strong bias against preservation of larger leaves within resin and amber, respectively. There is fast erosion from any open side of an inclusion as regularly observed with larger inclusions. If egg deposition was on food plant leaves, rare separation of such eggs from leaves feed may have been a prerequisite favoring complete embedding in resin and subsequent preservation as an amber inclusion.

Extant European species of Limenitis are associated with a narrow spectrum of plants on which the caterpillars feed and on which eggs are deposited. These are trees of the genus Populus (P. tremula, P. nigra) for Limenitis populi (Düring, 2020) and species of the Caprifoliaceae genus Lonicera (L. xylosteum, L. caprifolium, L. periclymenum, L. etrusca, L. implexa, L. alpigena, L. nummulariifolia) for Limenitis reducta and Limenitis camilla, the latter also being found at non-endemic Symphoricarpos albus which originates in North America (Eber, 1993; Tolman and Lewington, 1998).

Caterpillars of Neptis sappho (syn. Neptis aceris) live on leaves of Fabaceae (Lathyrus vernus, L. niger, Robinia pseudoacacia, and on other Fabaceae in Asia) (Lepidorum). In contrast, Neptis rivularis places its eggs at leaves of Rosaceae and caterpillars feed on such (Filipendula ulmaria [Rosoideae], Aruncus dioicus, Spiraea spp. [both Spiraeoideae]) (Lepiforum, 2022).

Adelpha species (“sisters”) live in southern Northern America and South America (Neotropics) (Lepiforum, 2024; Willmott, 2003). The genus has “certainly one of the widest host breadths of any nymphalid genus” (Willmott, 2003). The prominent North American Adelpha bredowii (California sister butterfly) feeds on oak (Quercus sp.) trees (Prudic et al., 2002).

Butterflies of extant genus Parthenos (Southeast Asia, India, Sri Lanka, Philippines, New Guinea) feed on tropical vines of Adenia (Passifloraceae) (pers. comm. A.V.L. Freitas, 2024). However, this plant genus has not been found in Baltic amber up to now. Caterpillars of the species Parthenos sylvia feed on a wide variety of plants, mainly Adena (Passifloraceae), but also Menispermaceae, and Cucurbitaceae (Nylin et al., 2013, Das-Tier-Lexikon).

There is only some direct evidence for the presence of the extant food-plant families of European Limenitis and Neptis in the Baltic amber forest (Spahr, 1993). A report on Populus (“Populites”) had been rejected, there is only evidence for the related genus Salix. Lonicera and Symphoricarpus (both Caprifoliaceae) are not known as Baltic amber, only Viburnum as pollen. Among Fabaceae (syn. Leguminosae) Acacia succini has been described. Some remains of Rosaceae are known from Baltic amber (Pteropetalum palaeogonum, and unspecified remains). The typical host plant families of Parthenos (Passifloraceae, Menispermaceae, Cucurbitaceae) seemingly are not known from Baltic amber (Spahr, 1993).

The habitat of extant European Limenitis and Neptis species are deciduous forests with Populus and Lonicera, but also dry, open, or mountainous forests (L. reducta), moist forests with Quercus, Carpinus, and often with Robinia pseudoacacia (Neptis sappho), moist or dry forests with Aruncus or Filipendula, or urban areas where Spiraea is cultivated there (Neptis rivularis) (Lepiforum, 2022).

Most interestingly, oak trees are hosts of the North American Adelpha bredowii. There is manifold evidence for several Quercus species and other Fagaceae in Baltic amber, most typical are their male inflorescences (Spahr, 1993; Sadowski, 2020). Also isolated trichomes might stem from these.

Today’s climate of the European / North African areal of the European genera Limenitis and Neptis is warm temperate (Köppen-Geiger, accessed 2020) (compare e.g., for Limenitis populi [Global Biodiversity Information Facility, accessed 2023]).

The climate of the Baltic amber forest (Sadowski, 2017) and the forest itself are reconstructed as “a thermophilic, humid-mixed forest similar to modern subtropical forests of Eastern and Southeastern Asia” (Alekseev, 2016). A later comprehensive study on Fagaceae hints to a warm temperate climate (Sadowski, 2020). Hence, today’s climate of the European genera of Limenitidinae to which the egg inclusion is related agrees with the climate reconstructed for the Baltic amber forest habitat.

The finding of the Limenitidinae egg from Eocene Baltic amber allows some conclusions on geological age of taxa: Wahlberg et al. (2013) date the origin of the family Nymphalidae to 90 mya and Chazotet al. (2019) the age of the superfamily Papilionoidea to 106,7 mya (lower to middle Cretaceous). There is fossil evidence of Nymphalinae already from the Late Eocene (Late Priabonian) of the Florissant Formation (US) (Scudder, 1889). Now, the finding of another subfamily (Limenitidinae) gives a minimum geological age and a calibration point, as well as direct fossil evidence for paleobiogeographical analyses (Chazot et al., 2021). The supposed age of Baltic amber was Mid Eocene (Lutetium) (44 mya by radiometric age dating of glauconite from Blue Earth) (Ritzkowski, 1997), revised to Upper Eocene (Priabonian, 33.9-37.8 mya) by paleontological evidence from Blue Earth (Kosmowska-Ceranowicz et al., 1997, Sadowski et al., 2020).

CONCLUSIONS

The find of a butterfly egg and its affiliation to the group of admirals (Limenitidinae) gives a minimum age for this subfamily of higher Lepidoptera by direct evidence, demonstrating also conservatism for the highly specialized egg sculpture. For taphonomy of amber inclusions, it shows that taxa not yet found and not to be expected to be preserved as adults can again be identified by their juvenile stages. Eggs or larvae are much smaller, often they have a different habitat. Consequently, embedding chances in amber-forming resins differ from that of adults.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. Veta is acknowledged for purchase of the specimen and providing high quality pictures with it. A.V.L. Freitas and V. Baranov are acknowledged for reviewing, critical reading, and helpful support improving the manuscript.

REFERENCES

Ackery, P.R., de Jong, R., and Vane-Wright, R. 1999. The Butterflies: Hedyloidea, Hesperioidea and Papilionoidea, p. 263--300. In Kristensen, N.P. (ed.), Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies, Volume 1: Evolution, Systematics and Biogeography, Handbook of Zoology, Vol. IV Arthropoda, Insecta, Part 35. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110804744.263

Alekseev, V.I. and Alekseev, P.I. 2016. New approaches for reconstruction of the ecosystem of an Eocene amber forest. Biology Bulletin, 43(1):75--86.

https://doi.org/10.1134/s1062359016010027

Branscheid, F. 1977. Fossile Schmetterlinge (Rhopalocera, Lepidopt.) aus dem Pliozän von Willershausen. Beiträge zur Naturkunde Niedersachsens, 30:85--88.

Brauckmann, C., Brauckmann, B., and Gröning, E. 2001. Anmerkungen zu den bisher beschrieben Lepidopteren aus dem Jung-Tertiär (Pliozän) von Willershausen am Harz. Jahresberichte des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins Wuppertal, 54:31--41.

Chapman, T.A. 1896. On the phylogeny and the evolution of the Lepidoptera from a pupal and oval standpoint. Transaction of the Entomological Society of London Part IV:567--587.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2311.1896.tb00969.x

Chazot, N., Wahlberg, N., Freitas A.V.L., Mitter, C., Labandeira, C., Sohn, J.-C., Sahoo, R.K., Seraphim, N., de Jong R., and Heikillä, M. 2019. Priors and posteriors in Bayesian timing of divergence analyses: the age of butterflies revisited. Systematic Biology, 68(5): 797--813.

https://doi.org/10.1093/sysbio/syz002

Chazot, N., Condamine, F.L., Dudas, G., Peña, C., Kodandaramaiah, U., Matos-Maraví, P., Aduse-Poku, K., Elias, M., Warren, A.D., Lohman, D.J., Penz, C.M., DeVries, P., Fric, Z.F., Nylin, S., Müller, C., Kawahara, A.Y., Silva-Brandão, K.L., Lamas, G., Kleckova, I., Zubek, A., Ortiz-Acevedo, E., Vila, R., Vane-Wright, R.I., Mullen, S.P., Jiggins, C.D., Wheat, C.W., Freitas, A.V.L., Wahlberg, N. 2021. Conserved ancestral tropical niche but different continental histories explain the latitudinal diversity gradient in brush-footed butterflies. Nature Communications, 12:5717.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-25906-8

Comstock, W.P. 1961. Butterflies of the American Tropics, The genus Anaea, Lepidoptera, Nymphalidae. The American Museum of Natural History, New York.

https://doi.org/10.4039/ent95672-6

Corbet, A.S. and Pendlebury, H.M. 1992. The butterflies of the Malay Peninsula, 4th Edition, revised by J.N. Eliot. Malayan Nature Society, Kuala Lumpur.

https://doi.org/10.31184/g00138894.731.1838

Cossey, J., PFN, undated online resource:

https://i.pinimg.com/originals/86/86/13/86861325c17b7b269ad5029b29e971e3.jpg

Das-Tier-Lexikon. Available at

https://www.das-tierlexikon.de/blauer-segler-edelfalter-schmetterlinge/ (accessed Sep. 24, 2024)

de Jong, R. 2017. Fossil butterflies, calibration points and the molecular clock (Lepidoptera: Papilionoidea). Zootaxa, 4270(1):001--063.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4270.1.1

Dhungel, B. and Wahlberg, N. 2018. Molecular systematics of the subfamily Limenitidinae (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae). PeerJ, 6:e4311.

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.4311

Döring, E. 1955. Zur Morphologie der Schmetterlingseier. Akademie Verlag, Berlin.

Durden, C.J. and Rose, H. 1978. Butterflies from the Middle Eocene: the earliest occurrence of fossil Papilionoidea (Lepidoptera). Texas Memorial Museum Pearce-Sellards Series, 29:1--25.

Düring, W. Großer Eisvogel. In Tagfalter in Rheinland-Pfalz. BUND RLP, 18. November 2020.

https://www.bund-rlp.de/fileadmin/rlp/Tiere_und_Pflanzen/Schmetterling/Schmetterlinge_W_Duering/Artenportraets_20/Grosser_Eisvogel_2020.pdf

Eber, G. 1993. Die Schmetterlinge Baden Württembergs. Band 1, Tagfalter I. Ulmer Verlag, Stuttgart.

https://doi.org/10.1163/187631292x00074

Fabricius, J.C. 1807. Systema Glossatorum (Brunovici). - Sammlung wissenschaftlicher Facsimile-Drucke, Band 1, 1938. Verlag Gustav Feller, Neubrandenburg.

https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/item/233494#page/5/mode/1up

Fischer, T.C., Michalski, A., and Hausmann, A. 2019. Geometrid caterpillar in Eocene Baltic amber (Lepidoptera, Geometridae). Scientific Reports, 9:17201.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-53734-w

Freitas, A.V.L. and Brown Jr., K.S, 2004. Phylogeny of the Nymphalidae (Lepidoptera). Systematic Biology, 53:363--383.

https://doi.org/10.1080/10635150490445670

Grimaldi, D. and Engel, M.S. 2005. Evolution of the Insects. Cambridge University Press, New York.

https://doi.org/10.2980/1195-6860(2006)13[290:eoti]2.0.co;2

Global Biodiversity Information Facility: international network and data infrastructure...about all types of life on Earth. GBIF Secretariat, Copenhagen, Denmark.

https://www.gbif.org/species/5132183 accessed Jan 30 2023.

Kharin, G.S. and Eroshenko, D.V. 2017. Amber in sediments of the Baltic Sea and the Curonian and Kaliningrad bays. Lithology and Mineral Resources, 52(5):392--400.

Köppen-Geiger: World Maps of Köppen-Geiger climate classification. Uni Vienna, Vienna, Austria. http://koeppen-geiger.vu-wien.ac.at accessed Dec 17 2022.

Kosmowska-Ceranowicz, B., Kohlman-Adamska, A., and Grabowska, I. 1997. Erste Ergebnisse zur Lithologie und Palynologie der bernsteinführenden Sedimente im Tagebau Primorskoje. Metalla Sonderheft - Neue Erkenntnisse zum Bernstein, 66:5--17.

Kristensen, N.P. and Skalski A. W. 1999. Phylogeny and Palaeontology, p. 7--25. In Kristensen, N.P. (ed.), Lepidoptera, Moths and Butterflies, Volume 1: Evolution, Systematics and Biogeography, Handbook of Zoology, Vol. IV Arthropoda, Insecta, Part 35. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin, New York.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110804744.7

Natur-in-NRW. Natur-in-NRW: Information on all species of animals and plants occurring in North.Rhine-Westphalia (Germany). https://www.natur-in-nrw.de/HTML/Tiere/Insekten/Schmetterlinge/Nymphalidae/TSNE-37.html (accessed Dec 22 2022).

Nylin, S., Slove, J., and Niklas Janz, N. 2013. Host plant utilization, host range oscillations and diversification in nymphalid butterflies: a phylogenetic investigation. Evolution, 68:105--124. https://doi.org/10.1111/evo.12227

Prudic, K.L., Shapiro, A.M., and Clayton, N.S. 2002. Evaluating a putative mimetic relationship between two butterflies, Adelpha bredowii and Limenitis lorquini. Ecological Entomology, 27:68--75.

https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0307-6946.2001.00384.x

Rafinesque, C.S. 1815. Analyse de la Nature, ou Tableau de l' Univers et des Corps Organisés. Jean Barravecceia: Palermo.

https://doi.org/10.5962/bhl.title.106607

Ritzkowski, S. 1997. K-Ar-Altersbestimmungen der Bernsteinführenden Sedimente des Samlandes (Paläogen, Bezirk Kaliningrad). Metalla, 66:19-23.

Sadowski, E.-M., Schmidt, A.R., Seyfullah, L.J., and Kunzmann, L. 2017. Conifers of the ‘Baltic amber forest’ and their palaeoecological significance. Stapfia, 106: 1--73.

Sadowski, E.-M., Schmidt A.R., and Denk, T. 2020. Staminate inflorescences with in situ pollen from Eocene Baltic amber reveal high diversity in Fagaceae (oak family). Willdenowia, 50:405--517. https://doi.org/10.3372/wi.50.50303

Sarto i Monteys, V., Hausmann, A., Solórzano-Kraemer, M.M., Hammel, J.U., Baixeras, J., Delclòs, X., and Peñalver, E. 2022. A new fossil inchworm moth discovered in Miocene Dominican amber (Lepidoptera: Geometridae). Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 120:104055.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsames.2022.104055

Schön, W., Rennwald, E., and Rodeland, J. 2024. Lepiforum. Determination of Butterflies and their preimaginal stages. Lepiforum e. V., Rheinstetten, Germany. Available at https://lepiforum.org. accessed October and November 2022.

Schön, W., Rennwald, E., and Rodeland, J. as Lepiforum e.V.:

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/taxonomy/Papilionoidea/Nymphalidae?view=0®ions (accessed Sep. 26, 2024)

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Limenitis_populi (accessed Dec. 22, 2022)

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Limenitis_camilla (accessed Dec. 22, 2022)

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Limenitis_reducta (accessed Dec. 22, 2022)

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Neptis_sappho (accessed Dec. 20, 2022)

https://lepiforum.org/wiki/page/Neptis_rivularis (accessed Dec. 20, 2022)

Scudder, S.H. 1889. The fossil butterflies of Florissant. Annual Report of the United States Geological Survey. 8:433--474.

Sohn, J.-C., Labandeira, C., Davis, D., and Mitter, C. 2012. An annotated catalogue of fossil and subfossil Lepidoptera (Insecta: Holometabola) of the world. Zootaxa. 3286:1--132.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3286.1.1

Sohn, J.-C. and Lamas, G. 2013. Corrections, additions, and nomenclatural notes to the recently published World catalogue of fossil and subfossil Lepidoptera. Zootaxa, 3599(4):395--399. https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.3599.4.8

Spahr, U. 1993. Systematischer Katalog und Bibliographie der Bernstein- und Kopal-Flora. Stuttgarter Beiträge zur Naturkunde B. 195:1--99.

Tolman, T. and Lewington, R. 1998. Die Tagfalter Europas und Nordwestafrikas. Franckh-Kosmos Verlags-GmbH & Co, Stuttgart.

Wahlberg, N., Wheat, C.W., and Pena, C. 2013. Timing and patterns in the taxonomic diversification of Lepidoptera (butterflies and moths). PLoS ONE. 8(11):e80875.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0080875

Willmott, K.R. 2003. The genus Adelpha: its systematics, biology and biogeography (Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Limenitidini). Scientific Publishers, Gainesville, Washington, Hamburg, Lima, Taipei, Tokyo.

https://doi.org/10.1603/0013-8746(2006)099[0184:tgaisb]2.0.co;2