A reassessment on Luchibang xingzhe: A still valid istiodactylid pterosaur within a chimera

A reassessment on Luchibang xingzhe: A still valid istiodactylid pterosaur within a chimera

Article number: 27.2.a41

https://doi.org/10.26879/1359

Copyright Palaeontological Association, August 2024

Author biographies

Plain-language and multi-lingual abstracts

PDF version

Supplementary Information

Submission: 14 November 2023. Acceptance: 24 July 2024.

ABSTRACT

Recently a new genus and species of istiodactylid pterosaur was named by Hone et al. (2020) based on a very complete skeleton from northern China. Although the possibility that the specimen was a chimera was raised by the authors themselves, checks of the specimen revealed no tampering with the specimen and it was considered genuine. The animal was posited as an unusual member of the clade, but characters from both the head and body supported the general identification as an istiodactylid. However, recent damage to the specimen because of flooding in the museum in which it is housed, has revealed that the rostrum and mandible were in fact added to the back of the skull and rest of the body of a second pterosaur. Here we correct the record on this specimen and suggest that Luchibang xingzhe as a taxon is still valid.

David W. E. Hone. Queen Mary University of London, Mile End Road, London, E1 4NS, UK. d.hone@qmul.ac.uk

Shunxing Jiang. Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Xizhimenwai Dajie 142, 100044 Beijing, China. jiangshunxing@ivpp.ac.cn

Adam J. Fitch. University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1215 West Dayton St, Madison, Wisconsin 53105, USA. afitch2@wisc.edu

Yizhi Xu. Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Xizhimenwai Dajie 142, 100044 Beijing, China and College of Earth and Planetary Sciences, University of Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China. xuyizhi@ivpp.ac.cn

Xing Xu. Institute of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Palaeoanthropology, Xizhimenwai Dajie 142, 100044 Beijing, China and CAS Center of Excellence in Life and Paleoenvironment, Beijing, 100044, China. xu.xing@ivpp.ac.cn

Keywords: pterosauria; pterodactyloidea; fossils; preparation; China

Final citation: Hone, David W. E., Jiang, Shunxing, Fitch, Adam J., Xu, Yizhi, and Xu, Xing. 2024. A reassessment on Luchibang xingzhe: A still valid istiodactylid pterosaur within a chimera. Palaeontologia Electronica, 27(2):a41.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1359

palaeo-electronica.org/content/2024/5273-luchibang-is-a-chinese-chimera

Copyright: August 2024 Palaeontological Association.

This is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0

INTRODUCTION

Fossil forgeries are a longstanding issue in Chinese collections (Stone, 2010), although this is neither a modern problem in palaeontology (e.g., see Romano and Pignatti 2021; Rossi et al., 2024) or one limited to China (e.g., Grimaldi et al., 1994; Scheyer et al., 2023). Forgeries by fossil collectors or dealers are created to improve the apparent quality of the material and so increase their value. Many of these are very crude and easy to detect (e.g., see Zipfel et al., 2010) and have been identified and not entered the scientific literature (Rowe et al., 2001), though others more sophisticated and have been described before their later discovery as being composites (Selden et al., 2019). Pterosaurs are among the taxa that have been suggested to be composites, with several specimens from Brazil suspected of being made of multiple constituent animals (e.g., Bennett, 1989; Dalla Vecchia et al., 2014; Cerqueira et al., 2021). It should though be noted that chimeric specimens can contain important scientific material (e.g., ‘Archaeoraptor’ Zhou et al., 2002) and some have only very minor additions or changes to them (e.g., the rostrum of the holotype of Microraptor gui Xu et al., 2003).

Recently, Hone et al. (2020) described and named a new large and complete skeleton of a Chinese istiodactylid, Luchibang xingzhe (ELDM 1000), that was purchased from a dealer. Istiodactylids are an unusual group of toothed pterodactyloid pterosaurs characterized by long snouts bearing triangular interdigitating teeth and a large nasoantobrital fenestra (Witton, 2013, p. 148). Numerous istiodactylids have been described from the Jiufotang Cretaceous fossil beds in northeastern China (e.g., Lü et al., 2008; Wang et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2019) and they are far more common in this region than from other sites.

In the original publication, the possibility was raised that the specimen had been tampered with and was a chimera, but no evidence of manipulation or alterations could be found (Hone et al., 2020, S2). This included examination of the edges and underside of the slab where possible, the presence of bones overlapping with one another between the cranium and various parts of the postcranium. Even some preparation of key areas of the specimen showed no apparent modifications (Hone et al., 2020, S2). The only issue was a mismatch in some of the postcranial anatomy to that of typical istiodactylids (see also Ozeki et al., 2023), although again this had been considered in the original paper and the discussion and analyses therein (Hone et al., 2020).

However, recent damage to the specimen has in fact revealed that the specimen has indeed been altered before it reached the Erlianhaote Dinosaur Museum, and that the specimen is a composite of two separate pterosaur fossils (Figure 1). Here we correct the record on the original specimen and the interpretations that come from this as presented by Hone et al. (2020). As we hold that the original description of the specimen remains an accurate reflection of the slab, and that the taxon Luchibang xingzhe remains valid (if restricted to the rostrum) and given the minimal impact on the scientific literature so far of the original paper, we have elected not to retract the original manuscript, but instead to offer this correction.

However, recent damage to the specimen has in fact revealed that the specimen has indeed been altered before it reached the Erlianhaote Dinosaur Museum, and that the specimen is a composite of two separate pterosaur fossils (Figure 1). Here we correct the record on the original specimen and the interpretations that come from this as presented by Hone et al. (2020). As we hold that the original description of the specimen remains an accurate reflection of the slab, and that the taxon Luchibang xingzhe remains valid (if restricted to the rostrum) and given the minimal impact on the scientific literature so far of the original paper, we have elected not to retract the original manuscript, but instead to offer this correction.

Institutional Abbreviations

ELDM, Erlianhaote Dinosaur Museum, Erlianhaote, Inner Mongolia, China.

DISCUSSION

Modification to the Specimen

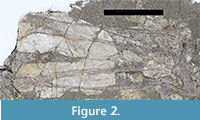

ELDM 1000 was recently on loan to the Inner Mongolia Museum of Natural History and part of the storage facility of the museum was unfortunately flooded and the specimen was submerged in water. The specimen was notably damaged as a result of this incident although there has been some small erosion to the surface of the bones and teeth of the anterior part of the skull. Importantly, the flooding has revealed that there are different matrices between the anterior part of the jaws (hereafter, part A of ELDM 1000) and the back of the skull and the postcranial skeleton (hereafter, part B of ELMD 1000), which strongly suggest this specimen is a chimera (Figure 1). Between the bones of parts A and B, there are four pieces of bones (forming the posterior part of the cranium and mandible), which are clearly not from part A and may, or may not, be from part B (Figure 2).

Evidence of coarse sands (not added by the flood) can be found surrounding the skeleton, which were not present in the shales that are with ELDM 1000A. This naturally suggests that the sands were added artificially and that most of the original matrix was removed during initial preparation before the specimen originally reached the museum. The sands were most likely glued to part A because they have been retained after the water damage from the flooding, and all the matrix of part A covering the mixed layer was lost.

Evidence of coarse sands (not added by the flood) can be found surrounding the skeleton, which were not present in the shales that are with ELDM 1000A. This naturally suggests that the sands were added artificially and that most of the original matrix was removed during initial preparation before the specimen originally reached the museum. The sands were most likely glued to part A because they have been retained after the water damage from the flooding, and all the matrix of part A covering the mixed layer was lost.

We think that parts A (and the possible a third section between A and B) were prepared nearly free of matrix and added into a major part of B. The specimen was then covered with glue and sand to hold it together. This layer was then covered with a stabilizing piece of plasterboard and then the entire specimen was turned and prepared down from the reverse side. As a result, A appears to be in the same matrix as B and there was no join visible.

In the original paper, Hone et al. (2020 S2) discussed the consistency of the specimen and the assessment of its integrity saying “examination and preparation in three distinct locations (between the scapula and mandible, between the right ramus of the mandible and 6th cervical, and finally in the space between the left ramus of the mandible, maxilla and seventh cervical vertebra) by DWEH and an independent observer revealed no evidence of tampering. There was no undercutting of the matrix, no glue or consolidants, and the matrix was entirely consistent in these areas and reached the bone naturally. Between the mandible, maxilla, and 7th cervical, the matrix was removed and revealed bone-to-bone contact between each element”. Despite this work and the attention given to the fossil, this was clearly insufficient to detect the changes made to the specimen.

The specimen was recently highlighted by Ozeki et al. (2023) as being potentially a chimera with the skull being separate from the postcranium. Notably, however, the join between ELDM 1000A and B is not as suggested by Ozeki et al. (2023), but actually is at the posterior part of the nasoantorbital fenestra. Even where the specimen was suggested to be a composite, this was so well concealed that the join was no in the place suggested.

Papers on determining if fossils are genuine advocate close examination of the material as a major step in such assessments (Mateus et al., 2008). Other suggested methods to assess specimens for fakes (e.g., CT Scanning, Rowe et al., 2016, UV light and chemical analysis Mateus et al., 2008) are not always practical and in the case of ELDM 1000 for example, the original slab is both large and fragile. Our own observations with UV light and photography have shown specimens from Liaoning that we know to be genuine can give odd UV reflectance patterns and appear to have been treated or manipulated when they have not.

Taxonomic Identity

The original diagnosis for the taxon was as an “[i]stiodactyloid pterosaur that can be distinguished from others in the group by two unique characters: a large, rectangular sternum with a straight posterior edge, and a long femur that is more than 80% of the length of the ulna. It can be further distinguished from other istiodactylids by the following combination of characters: rostrum with no dorsal expansion anteriorly; very well-spaced teeth in the posterior part of the jaw; a dentary symphysis that is more than four times longer than wide in dorsal view; long and narrow mandibular rami (approximately 20 times longer than wide in dorsal view)” (Hone et al., 2020).

Clearly the two given autapomorphies relate to the postcranium and are now irrelevant as this is from a separate specimen, and indeed potentially not an istiodactylid (see below). However, the combination of traits given in the diagnosis in order to diagnose this animal as being unique all refer to the upper and lower jaws which form a single unique part. As such, we suggest that the name Luchibang xingzhe would still be valid, if restricted to a very limited specimen (i.e., ELDM 1000A as shown here in Figure 1). The character of the mandibular rami being 20 times longer than wide in dorsal view becomes problematic as their exact length is not known, although the fact that these are “long and narrow” is clearly still correct since as preserved the rami are still at least 13 times longer than wide.

Other Chinese istiodactylids have been named from similarly limited material (e.g., Liaoxipteru s, Dong and Lü, 2005) and characters of the jaws and teeth have been important components of defining genera and species in this clade in general (e.g., Hongshanopterus, Wang et al., 2008; Mimodactylus, Kellner et al., 2019). More recently named taxa such as Lingyuanopterus (Xu et al., 2022) show comparisons and diagnoses that would continue to separate Luchibang from them and keep it as a valid taxon. As such, despite the limited material here, we suggest that traits are therefore sufficient to diagnose a distinct taxon. Luchibang xingzhe would be retained as a valid name, though referring now only to this section of ELDM 1000 (see also Ozeki et al., 2023 who took a similar position treating the skull as a separate and potentially valid unit).

Luchibang xingzhe Hone et al., 2020

Holotype. Rostrum and anterior mandible of ELDM 1000

Revised Diagnosis. Distinguished from other istiodactylids by the following combination of characters: rostrum with no dorsal expansion anteriorly; very well-spaced teeth in the posterior part of the jaw; a dentary symphysis that is more than four times longer than wide in dorsal view; long and narrow mandibular rami (approximately 20 times longer than wide in dorsal view.

Other material. Ozeki et al. (2023) suggest that the postcranial material belongs to the tapejaroid Sinopterus or a closely related taxon based on proportional similarities to Sinopterus. We agree that this postcranial material represents a tapejaroid, and it does share one feature with Sinopterus and other tapejaromorphs to the exclusion of other pterosaurs: a broad tubercle along the coracoid’s ventroposterior margin [124(1)]. However, it also possesses several features differing from Sinopterus and aligned with those seen in Azhdarchomorpha (all taxa more closely related to the azhdarchids than tapejarids; see Pêgas et al., 2022): a deep flange present on the anteroventral surface of the coracoid [123(1)]; humerus is less than 80% the length of the femur [127(0)]. It does also lack a key feature of the rest of Azhdarchomorpha: mid-cervical vertebrae longer than three times their width [109(2,3)] (as opposed to [109(1)] of this postcranial material, in which the mid-cervicals are longer than wide but their length is not greater than three times their width). Thus, we consider the postcrania to represent an indeterminate member of Azhdarchomorpha.

Locality Information

The locality information for the specimen as hailing from the Yixian Formation in Nei Mongol, northern China was provided with the original material. In the light of the chimeric nature of the specimen, this does further raise issues about the likely origins of both A and B parts. It is impossible to determine the locality and horizon based on the available matrix (some of which has itself been altered). The main part B (potentially an azhdarchomorph pterosaur) is represented by chaoyangopterids in the Jehol Biota. All the known chaoyangopterid specimens were from the Jiufotang Formation (Wang et al., 2023). Istiodactylids are almost from the Jiufotang Formation, except for Luchibang, only one reliable individual out of dozens of specimens was reported from the Yixian Formation (Ozeki et al., 2023). Hence, we must be cautious about the original information of the locality and horizon of the holotype, although it remains likely that is it from the Jehol Group of western Liaoning.

Clades

Although Hone et al. (2020) did run separate phylogenetic analyses with just the cranial and postcranial material included, this does not match the split we now know to be present in ELDM 1000. As a result, we took the original analysis and split off the characters from only the rostrum rather than the whole skull and repeated our analysis. The topology recovered here (excluding Luchibang and the postcranial material) is almost identical to that recovered in Hone et al., (2020). Luchibang is recovered in a polytomy with Nurhachius ignaciobritoi and a clade consisting of Liaoxipterus brachyognathus and Istiodactylus (in Hone et al., 2020, Luchibang is recovered as closer to the latter clade than to N. ignaciobritoi; this is the case also in Ozeki et al., 2023). The separate postcranial OTU (with a few differences in the coding from the prior iteration, see Supplementary Information) is recovered here as a tapejaroid. The only tapejaroid postcranial synapomorphy (and the only tapejaroid synapomorphy found in the postcranial OTU) is [128(0)], the humerus+ulna length being less than 80% of the femur+tibia length.

Interpretation

This obviously greatly changes the interpretations of the original fossil; however we stand by our original description of the material in this context and the figures and text do accurately describe the anatomical details present. Below we elaborate on the issues that this raises. As the paper describing and naming Luchibang was only published recently, it has fortunately had only a limited impact on the technical scientific literature. Of the peer-reviewed papers that have cited Hone et al. (2020), we offer the following comments and clarifications:

Beccari et al. (2021) used the data matrix from Hone et al. (2020) as the basis of their phylogenetic analysis but did otherwise comment on Luchibang or istiodactylid relationships and so we do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Holgado (2021) cited the results of the phylogeny of Hone et al. (2020) only in terms of the positon of the ornithicheirids Ornithocheirus and Tropeognathus relative to one another and noting that the results were consistent with other papers, and so we do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Jiang et al. (2021) did use characters from Hone et al. (2020) to differentiate this from the pteranodontoid Yixianopterus jingangshanensis but based on traits from the dentition and rostrum of Luchibang, and so this should not affect the taxonomic work or traits used to diagnose the former. Therefore, we do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Zhou et al. (2021) cite Hone et al. (2020) only in the context of the problem of assessing fossils for signs of tampering and so we do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Hone (2023) in his paper on the diversity of pterosaur sterna included that of ELDM 1000 as an istiodactylid and now considered tapejaroid (see above). This is a clear difference from the original publication.

Xu et al. (2022; naming a new istiodactylid Lingyuanopterus) and Ozeki et al. (2023; describing new material of the istiodactylid Nurhachius) included Luchibang in their phylogenetic analyses. In both analyses Luchibang is recovered as an istiodactylid, though Xu et al. (2022) includes the entire composite and Ozeki et al. (2023) the actual Luchibang holotype and the cranial portions of the postcranial specimen. Given this and the small differences in coding between the coding of all the cranial material in the composite vs. just those of the holotope, we do not think that the revisions we presented would have notable effects on the topologies of these analyses. Xu et al. (2022) also carried out several taxonomic comparisons and while there are some similarities between the two, the comparisons were based on the cranium and dentition and not the postcranium, and a number of traits present in the rostrum of Luchibang still serve to distinguish it from Lingyuanopterus. We therefore do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Ozeki et al. (2023) noted that they considered ELDM 1000 to be a composite and coded the cranium as separate to the rest of the specimen in their phylogenetic analysis. This should reduce any issues around the inclusion of Luchibang, although they considered the entire skull to have been added on ELDM 1000 when in practice this was only the rostrum. However, we do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

You et al. (2023) cited Hone et al. (2020) in their supplementary data, but Luchibang did not feature in their dataset (S4), and it is not clear if any measurements or the phylogeny was included in the published analyses. We therefore do not consider this work to have been negatively affected.

Sweetman (2023) noted that most Chinese istiodactylids are from the Jiufotang Formation with Luchibang an apparent exception. As noted above, this may now be incorrect, but we cannot confirm this.

Ecology and Ontogeny

The original ecological interpretation of Luchibang as a long-limbed wader (Hone et al., 2020) is not now supported. There is now no reason to think it was any different in general ecology from any other istiodactylid (though the biology of these animals remains uncertain and somewhat contentious, e.g., see Witton, 2013). The diversity of istiodactylid limb proportions also being much broader than previously considered (Hone et al., 2020: figure 9) is similarly not supported. There is no reason to think that the rest of this animal was unusual compared to other istiodactylids.

Similarly, although the main part of the specimen is clearly a young animal showing numerous signs of immaturity (Hone et al., 2020), this is less apparent for the rostrum and mandible alone. Aside from the bone surface texture, there are few traits used to classify the ontogenetic status of pterosaurs that could be seen in this part of the skeleton (Kellner, 2015). Thus, although the skull and mandible here are clearly not of a very young animal, it is impossible to say how old the individual may have been or how large it could grow. It is clearly a good fit size-wise for the postcranium to which it is attached and not dissimilar in size to other istiodactylids suggesting a moderate wingspan of c. 3 m, but this should no longer be considered a young animal that would have been much larger in adulthood.

CONCLUSIONS

Fossil forgeries remain a clear, though likely small, problem for palaeontology. Fossils continue to be purchased or donated to collections that were not collected and documented by academics and their exact origins are unknown or uncertain. As seen here, even close examination of material while searching for evidence of fabrication can miss such tampering given the detail of the work done. Although suspicion had been cast on this specimen before, it may not have been discovered that this had been altered were it not for the accidental damage to ELDM 1000, and it is not always possible or practical to heavily prepare or otherwise alter fragile specimens to search for changes made to them.

In this case, despite our checks and concerns, the original authors were deceived by the changes made to the specimen. We hope that this work serves to correct the record on this specimen and any echoes that the original paper has had on the scientific literature. The original authors are chastened by this experience and trust that this serves a timely warning for others assessing the validity of specimens offered to them.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the editor and two anonymous referees for their helpful comments on an earlier version of this manuscript.

REFERENCES

Andres, B., Clark, J., and Xu, X. 2014. The Earliest Pterodactyloid and the Origin of the Group. Current Biology, 24(9):1011-1016.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2014.03.030

Beccari, V., Pinheiro, F.L., Nunes, I., Anelli, L.E., Mateus, O., and Costa, F.R. 2021. Osteology of an exceptionally well-preserved tapejarid skeleton from Brazil: Revealing the anatomy of a curious pterodactyloid clade. PloS one, 16(8):p.e0254789.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254789

Bennett, S.C. 1989. A pteranodontid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Peru, with comments on the relationships of Cretaceous pterosaurs. Journal of Paleontology, 63(5):669-677.

https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022336000041305

Cerqueira, G.M., Santos, M.A., Marks, M.F., Sayão, J.M., and Pinheiro, F.L. 2021. A new azhdarchoid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil and the paleobiogeography of the Tapejaridae. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica, 66(3):555-570.

https://doi.org/10.4202/app.00848.2020

Dalla Vecchia, F.M., Bosch, R., Fortuny, J., and Galobart, À. 2014. The pterodactyloid pterosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Brazil at the CosmoCaixa Science Museum (Barcelona, Spain). Historical Biology, 27(6):729-748.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2014.961449

Dong, Z. and Lü., J. 2005. A new ctenochasmatid pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous of Liaoning Province. Acta Geologica Sinica-English Edition, 79(2):164-167.

Grimaldi, D.A., Shedrinsky, A., Ross, A., and Baer, N.S. 1994. Forgeries of fossils in “amber”: history, identification and case studies. Curator: The Museum Journal, 37(4):251-274.

https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1994.tb01023.x

Holgado, B. 2021. On the validity of the genus Amblydectes Hooley 1914 (Pterodactyloidea, Anhangueridae) and the presence of Tropeognathinae in the Cambridge Greensand. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 93(2).

https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765202120201658

Hone, D.W. 2023. The anatomy and diversity of the pterosaurian sternum. Palaeontologia Electronica, 26(1):a12.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1261

Hone, D.W., Fitch, A.J., Ma, F., and Xu, X. 2020. An unusual new genus of istiodactylid pterosaur from China based on a near complete specimen. Palaeontologia Electronica, 23(1):a09.

https://doi.org/10.26879/1015

Jiang, S., Zhang, X., Cheng, X., and Wang, X. 2021. A new pteranodontoid pterosaur forelimb from the upper Yixian Formation, with a revision of Yixianopterus jingangshanensis. Vertebrata Palasiatica, 59(2):81.

https://doi.org/10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.201124

Kellner, A.W.A. 2015. Comments on Triassic pterosaurs with discussion about ontogeny and description of new taxa. Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, 87:17875.

https://doi.org/10.1590/0001-3765201520150307

Kellner, A.W., Caldwell, M.W., Holgado, B., Vecchia, F.M.D., Nohra, R., Sayão, J.M., and Currie, P.J. 2019. First complete pterosaur from the Afro-Arabian continent: insight into pterodactyloid diversity. Scientific Reports, 9(1):1-9.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-54042-z

Lü, J.C., Xu, L., and Ji, Q. 2008. Restudy of Liaoxipterus (Istiodactylidae: Pterosauria) with comments on the Chinese istiodactylid pterosaurs, Zitteliana B, 28:229-241.

Mateus, O., Overbeeke, M., and Rita, F. 2008. Dinosaur frauds, hoaxes and “Frankensteins”: how to distinguish fake and genuine vertebrate fossils. Journal of Paleontological Techniques, 2:1-5.

Ozeki, M., Tsukuba, D., Unwin, D.M., Bell, P., Li, D.-Q., and Lida, X. 2023. A new pterosaur specimen from the Lower Cretaceous Yixian Formation of Liaoning Province, China: the oldest fossil record of Nurhachius. Historical Biology, 36:1625–1638.

https://doi.org/10.1080/08912963.2023.2222127

Pêgas, R.V., Holgado, B., David, L.D.O., Baiano, M.A., and Costa, F.R. 2022. On the pterosaur Aerotitan sudamericanus (Neuquén Basin, Upper Cretaceous of Argentina), with comments on azhdarchoid phylogeny and jaw anatomy. Cretaceous Research, 129:104998.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2021.104998

Romano, M. and Pignatti, J. 2021. The fossil merchant from Verona: the first written testimony of paleontological forgery in Italy. Rendiconti Online della Societa Geologica Italiana, 55:54-63.

https://doi.org/10.3301/ROL.2021.14

Rossi, V., Bernardi, M., Fornasiero, M., Nestola, F., Unitt, R., Castelli, S., and Kustatscher, E. 2024. Forged soft tissues revealed in the oldest fossil reptile from the early Permian of the Alps. Palaeontology, 67:e12690.

https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12690

Rowe, T., Ketcham, R.A., Denison, C., Colbert, M., Xu, X., and Currie, P.J. 2001. The Archaeoraptor forgery. Nature, 410(6828):539-540.

https://doi.org/10.1038/35069145

Rowe, T.B., Luo, Z.X., Ketcham, R.A., Maisano, J.A., and Colbert, M.W., 2016. X-ray computed tomography datasets for forensic analysis of vertebrate fossils. Scientific data, 3(1):160040.

https://doi.org/10.1038/sdata.2016.40

Scheyer, T.M., Oliveira, G.R., Romano, P.S., Bastiaans, D., Falco, L., Ferreira, G.S., and Rabi, M. 2023. A forged ‘chimera’ including the second specimen of the protostegid sea turtle Santanachelys gaffneyi and shell parts of the pleurodire Araripemys from the Lower Cretaceous Santana Group of Brazil. Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, 142(1):61.

https://sjpp.springeropen.com/articles/10.1186/s13358-023-00271-9

Selden, P.A., Olcott, A.N., Downen, M.R., Ren, D., Shih, C., and Cheng, X. 2019. The supposed giant spider Mongolarachne chaoyangensis, from the Cretaceous Yixian Formation of China, is a crayfish. Palaeoentomology, 2(5):515-522.

https://doi.org/10.11646/PALAEOENTOMOLOGY.2.5.15

Stone, R.D. 2010. Altering the past: China’s faked fossil problem. Science, 330:1740-1741.

https://doi.org/10.1126/science.330.6012.1740

Sweetman, S.C. 2023. Pterosaur teeth from the Lower Cretaceous (Valanginian) Cliff End Bone Bed, Wadhurst Clay Formation, Wealden Supergroup of southern England, and their possible affinities. Cretaceous Research, 151:105622.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cretres.2023.105622

Wang, X., Campos, D.A., Zhou, Z.-H., and Kellner, A.W.A. 2008. A primitive istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterodactyloidea) from the Jiufotang Formation (Early Cretaceous), northeast China: Zootaxa, 18:1-18.

https://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.1813.1.1

Wang, X., Kellner, A.W.A., Jiang, S., Chen, H., Costa, F.R., Cheng, X., Zhang, X., Nova, B.C.V., Campos, D.d.A., Sayao, J.M., Rodrigues, T., Bantim, R.A.M., Saraiva, A.A.F., and Zhou, Z. 2023. A new toothless pterosaur from the Early Cretaceous Jehol Biota with comments on the Chaoyangopteridae. Scientific Reports, 13:22642.

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-023-48076-7

Witton, M.P. 2013. Pterosaurs. Princeton University Press, Princeton. 291 pp.

https://doi.org/10.1515/9781400847655

Xu, X., Zhou, Z., Wang, X., Kuang, X., Zhang, F., and Du, X. 2003. Four-winged dinosaurs from China. Nature, 421(6921):335-340.

https://doi.org/10.1038/nature01342

Xu, Y., Jiang, S., and Wang, X. 2022. A new istiodactylid pterosaur, Lingyuanopterus camposi gen. et sp. nov., from the Jiufotang Formation of western Liaoning, China. PeerJ, 10:e13819.

https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.13819

Zhou, X., Pêgas, R.V., Leal, M.E., and Bonde, N., 2019, Nurhachius luei, a new istiodactylid pterosaur (Pterosauria, Pterodactyloidea) from the Early Cretaceous Jiufotang Formation of Chaoyang City, Liaoning Province (China) and comments on the Istiodactylidae. PeerJ, 7:e7688.

https://doi.org/10.7717/apeerj.7688

Zhou, X., Pêgas, R.V., Ma, W., Han, G., Jin, X., Leal, M.E., Bonde, N., Kobayashi, Y., Lautenschlager, S., Wei, X., and Shen, C. 2021. A new darwinopteran pterosaur reveals arborealism and an opposed thumb. Current Biology, 31(11):2429-2436.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2021.03.030

Zhou, Z., Clarke, J.A., and Zhang, F. 2002. Archaeoraptor’s better half. Nature, 420(6913):285-285.

https://doi.org/10.1038/420285a

Zipfel, B., Yates, C., and Yates, A.M. 2010. A case of vertebrate fossil forgery from Madagascar. Palaeontologia Africana, 45:pp.29-31.